Over 25,000 Jewish partisans fought back against the Nazis. A new film tells 8 of their stories.

Director Julia Mintz interviewed some of the last surviving partisans for her documentary ‘Four Winters’

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

Documentary filmmaker Julia Mintz has been collecting stories for over 20 years. A little over a decade ago, one stopped her in her tracks.

It was the story of a young girl who encamped in a ditch and exploded a Nazi train heading to the frontlines.

“I thought, ‘Who is this little girl? I want to make a movie about her,’” Mintz said in a phone interview. As she did more research, she learned that this girl wasn’t alone, but a member of a network of Jewish partisans numbering over 25,000 who fought Nazis and their collaborators in the woods of Belarus, Ukraine and Poland.

“I had known about the Bielski brigade – but I knew that was a family camp,” Mintz said. “I had known about Hannah Senesh and a few others, but I had no real understanding of the thousands and thousands of people that were part of the armed Jewish resistance during World War II. And so when I stumbled upon this story, there was no doubt in my mind that I needed to learn more.”

“Four Winters,” Mintz’s first feature documentary as writer, director and producer, tells the story of eight partisans reflecting on their time in the primeval forests. It’s a stirring portrait of survival, grief and struggles with faith and moral uncertainty.

A veteran producer and production designer on films like “Mr. Soul!” and “Soundtrack for a Revolution,” Mintz says she made “Four Winters” “upside down,” interviewing nearly three dozen partisans before she had secured financing for the film. Since many of the fighters, though largely young people when they fought for their survival in the wilderness, were by then in their 90s, Mintz knew time was of the essence.

Mintz wanted the partisans to tell their own stories, and made a deliberate choice to not yield the floor to any historian talking heads.

“I know that for years to come, people will pontificate and there’ll be all sorts of scholarly research that can contribute to this subject,” Mintz said. “But this is the final telling and I wanted us to just have the opportunity to be with them in the intimacy and the rawness and the grit — and in the promise of witnessing and carrying their stories forward.”

Key to conveying how the partisans lived was the photography of Faye Schulman, one of the only known Jewish partisans to document the experience in pictures. Mintz rushed to Schulman’s home in Toronto, taking flatbed scanners with her. Schulman’s images, of young people smoking cigarettes while draped with fur-lined coats and bandoliers, life in the camp and even the surgery of a wounded comrade, serve as powerful testimony to an often overlooked chapter in the war. Schulman died last year, but saw a cut of the film, in which she tells a gutting story about how she burned down her own home, where, with her family dead and her living in the wilderness, the Nazis had set up a police headquarters.

The eight partisans detail how they ate (pork, which kept better than beef, was a regular meal – though, for one woman who preferred to remain kosher, a chicken was acquired); smuggled ammunition (“women have more places to hide weapons than men,” one woman tells us); and even worshiped. One Erev Yom Kippur, without the aid of prayer books, a man sang Kol Nidre from memory.

“We didn’t give up our faith,” Isadore Farbstein, a partisan from Parczew, Poland, says in the film. Though later he explains that, after a gentile villager threatened to expose him as Jewish, he vowed, if he should have a son, to never circumcise him.

Mintz chose to premiere the film around the High Holidays, a time of spiritual reflection. On a personal level, the yearslong production prompted her to reassess the narrative of the Holocaust, not just from the perspective of the partisans, but the millions more who couldn’t escape.

“This film shatters the myth of Jewish passivity, but it shatters it with the nuance of a new understanding,,” Mintz said. “Part of that too is understanding what it was like to be inside the train and why people didn’t all jump out.”

Mintz came to realize that the partisans managed to escape to the woods and take up arms through incredible strokes of luck. The many more Jews who were deported or sent on death marches may not have acted to disarm their guards or flee for a very good reason: Doing so could endanger others.

Most of the partisans in the documentary have passed away, though one, Michael Stoll, who recounts his escape from a cattle car into the woods, attended a recent screening at the Berkshire Film Festival, where he received a standing ovation.

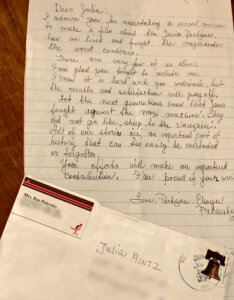

Keeping with the spirit of her film, which eschews narration and talking head experts, Mintz read a letter from one of her subjects, Chayelle Palevsky, letting a partisan get the final word.

“Let the next generations know that Jews fought against the Nazi machine,” Palevsky wrote. “They did not go like sheep to the slaughter. All of our stories are an important part of history that can too easily be overlooked or forgotten.”

,

“Four Winters” opens Friday, Sept. 16 at Film Forum. Tickets and information can be found here.