At the core of ‘Oppenheimer,’ a debate about how to be Jewish

Christopher Nolan’s explosive film centers a Jew committed to his faith and one who was indifferent to it

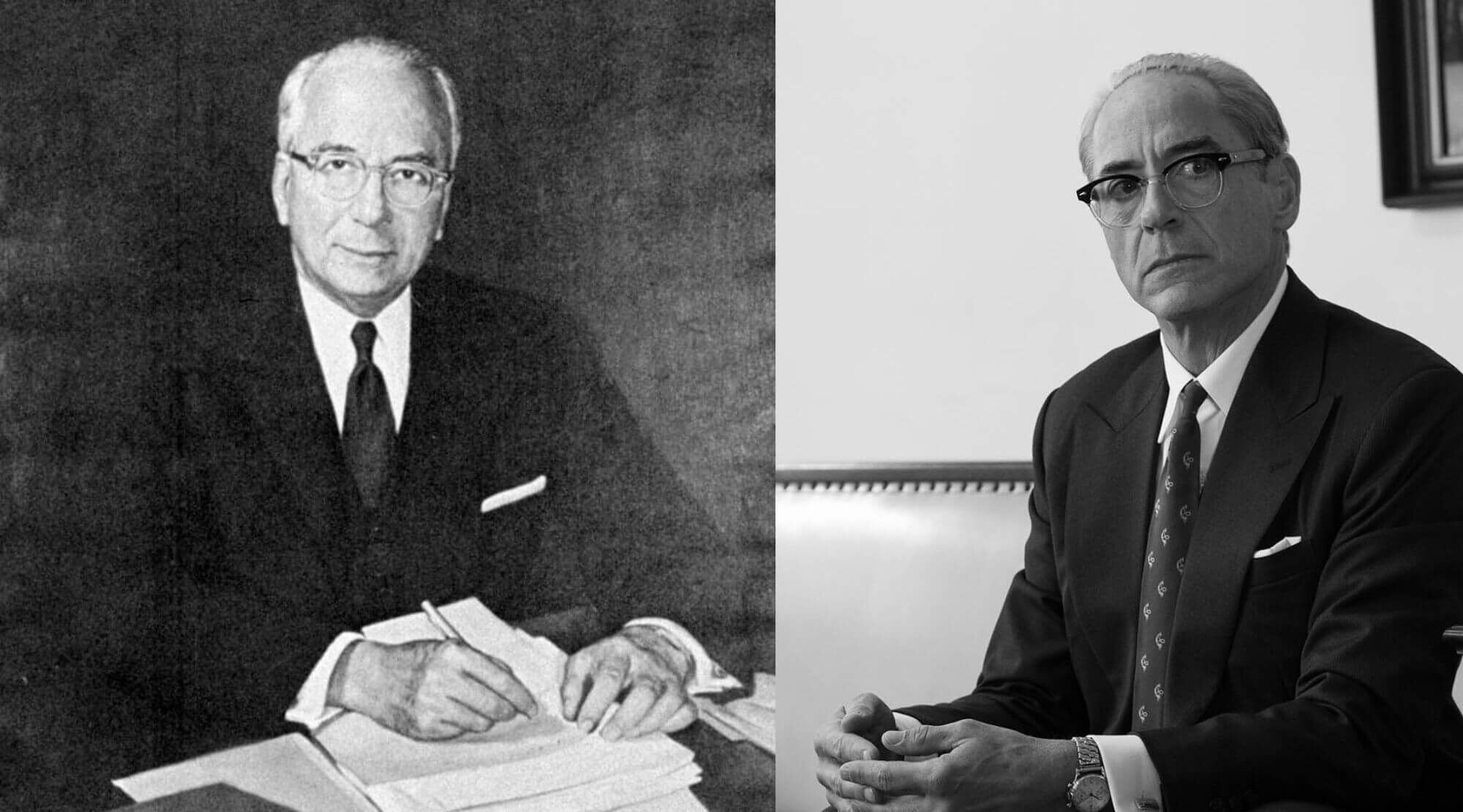

In a key scene in Oppenheimer, the physicist embarrasses Strauss before the Joint Committee on Atomic Energy, prompting Strauss’ crusade to humiliate Oppenheimer. Courtesy of NBC Universal

On a sprawling green campus, shown in stark black and white, a fastidious man in glasses prepares to meet a god among men.

The man in the glasses is Lewis Strauss, a trustee for the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey. The god is J. Robert Oppenheimer, erstwhile leader of the Manhattan Project’s Los Alamos Laboratory, whom Strauss is courting to direct the Institute in 1947. Their introduction gets off to a rocky start.

“Mr. Strauss,” Oppenheimer says by way of greeting — the address is wrong on two counts. Strauss is a Navy Reserve admiral, and he pronounces his name “Straws,” in the Southern fashion. Strauss gently corrects him.

Never at a loss for a quick retort, the father of the atom bomb, haughty in his porkpie hat, says, “Ah-penheimer, Oh-penheimer. No matter how you say it they know I’m Jewish.”

Strauss replies that he’s president of Temple Emanu-El. Oppenheimer presses for more credentials — is he a physicist by training? No, he’s more of a hobbyist. In fact, before becoming a financier, he made his money selling shoes.

“Lewis Strauss was once a lowly shoe salesman?” Oppenheimer smirks.

“No, just a shoe salesman,” Strauss answers. He refuses to be lowered.

Strauss and Oppenheimer, fact and fiction

The scene comes early in Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer, and it is largely imagined.

Oppenheimer’s first meeting with Strauss, who would, less than a decade later, as chair of the Atomic Energy Commission, lead a crusade against Oppenheimer’s security clearance, took place years earlier, during the war. But the showdown between these two men, who wore their politics, their public service and their Jewishness so differently, is at the volatile center of Nolan’s drama. The film covers around three decades of Oppenheimer’s life, from his prolonged adolescence as a graduate student at the University of Cambridge to his dramatic time as director at Los Alamos and his emergence as a public figure.

Nolan frames the biography with two inquisitions: Oppenheimer’s infamous AEC hearing in 1954, which saw him lose his security clearance; and Strauss’ 1959 grilling in the Senate, where he was denied confirmation as Eisenhower’s secretary of commerce — largely due to his treatment of Oppenheimer. The two men, who jousted about the implications of nuclear power and what to do with it, are made to justify their whole lives before committees.

Fiction couldn’t dream up better foils.

Before his work on the bomb, Oppenheimer was an active “fellow traveler” of Communists. Strauss was an arch conservative and a protege of Herbert Hoover. Oppenheimer was a product of Harvard, Cambridge and Göttingen; Strauss was a high school graduate. Oppenheimer was a New Yorker, raised in a home with paintings by Picasso and Van Gogh; Strauss grew up in a modest German-Jewish family in Richmond, Virginia where, he wrote in his memoir, he “knew men who had known Robert E. Lee.”

Oppenheimer’s German-born father and Baltimore-born mother raised him without Jewish tradition in the milieu of the Society for Ethical Culture, a Jewish-founded movement with a secular, humanistic and assimilationist bent. Strauss was a committed Reform Jew. He was involved in a dizzying amount of Jewish organizations and served as president of Temple Emanu-El in Manhattan for a decade. In his youth, he didn’t work on Shabbat.

For all their differences, the two men shared an interest in science and, at least on paper, a faith.

In the account of Kai Bird and Martin Sherwin’s American Prometheus, which provides the basis for Nolan’s film, Oppenheimer and Strauss’ clash was built on a foundation of personal slights heightened by the climate of the McCarthy era. On several occasions, their disagreements on policy — Strauss was security-minded and supported the development of the hydrogen bomb; Oppenheimer was for nuclear transparency in the international community and against making thermonuclear weapons — manifested in Oppenheimer publicly humiliating Strauss, earning his suspicion and his hatred.

Bad chemistry

The nominal reasons for the 1954 review of Oppenheimer’s clearance involved his Communist ties, known to the AEC for years, and dredged up in a letter by Joint Committee on Atomic Energy staffer William L. Borden, based on documents Strauss made available to him. But it is also possible the animus underlying Strauss’ mission to erect a “blank wall” between Oppenheimer and the government’s secrets was rooted in something more tribal: that Strauss, a dedicated Jew, saw in Oppenheimer a coreligionist who shirked his heritage for leftist causes. Did Strauss look at Oppenheimer and see a shanda? And should Jews, who may sympathize with Oppenheimer, consider Strauss one?

“They were oil and water. They had bad chemistry,” Bird said in a phone interview. “Strauss was offended by Oppenheimer’s behavior, and then he thinks in the back of his mind, ‘This is a brash young man who doesn’t take his Jewish ancestry seriously,’ and that grated on him too.”

‘He was Jewish, but he wished he weren’t and tried to pretend he wasn’t’

Oppenheimer was more comfortable with Sanskrit than Hebrew. After the first test of the atom bomb, he recalled not a line from the biblical prophets, but the Bhagavad-Gita: “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.” To make the matter more pluralistic, he named the test Trinity, after a poem by John Donne, which begins “batter my heart, three person’d god.”

Oppenheimer’s friend Isidor Isaac Rabi lamented that his interests strayed from his own tradition. Hearing he was reading Hindu scripture, Rabi wondered “why not the Talmud?”

Nolan’s film neatly lays out the differences between these two men. Meeting for the first time in 1928 on a train to Zurich, Rabi, played by David Krumholtz, sees common ground in their origins, but marvels at Oppenheimer’s command of Dutch. When Oppenheimer tells him he learned it in just over a month, Rabi calls him a “shvitzer” (showoff), drawing a blank look.

“Dutch in six weeks and you never learn Yiddish?” Rabi asks.

“We don’t speak it much on our side of the Park,” Oppenheimer smiles.

When Rabi asks Oppenheimer if he ever feels like people like them aren’t welcome in Europe, he isn’t sure who he means, venturing “physicists” — that identity was always front of mind for Oppenheimer.

Rabi, who was raised Orthodox and insisted on introducing himself as an Austrian Jew while in Germany was, perhaps more than anyone, concerned with Oppenheimer’s Jewishness — or lack thereof.

“Oppenheimer was Jewish, but he wished he weren’t and tried to pretend he wasn’t,” Rabi said, adding that he renounced that heritage at his own peril. For Rabi, Oppenheimer’s neglect of his Jewishness made it so his dear friend “never got to be an integrated personality.”

Bird described Oppenheimer’s relationship to Jewishness as “ambivalent,” though he encountered antisemitism in Harvard and Europe.

When the AEC dragged Oppenheimer through his closed-door hearing, two sympathizers compared his plight to that of Captain Alfred Dreyfus. In a lengthy October 1954 piece for Harpers, titled “We Accuse!” after Emile Zola’s J’Accuse, journalist brothers Stewart and Joseph Alsop emphasized Oppenheimer’s background in an indictment of Strauss and Hungarian Jewish physicist Edward Teller, who developed the hydrogen bomb and testified against Oppenheimer.

Oppenheimer, the Alsops wrote, was born “into a prosperous, cultivated and liberal Jewish family,” and “the whole household was imbued with the rabbinical respect for things of the mind and with the hope of progress made all the sweeter by the memory of dark things left behind, that often distinguished Jews of their sort in that simpler and better time.”

It was overstating its case.

Oppenheimer and Dreyfus

The Forverts received the Harpers article with skepticism.

“What is this comparison composed of between Oppenheimer and Dreyfus?,” contributor Nathaniel Zalowitz wrote on Oct. 10, 1954. “Is Oppenheimer thereby a victim of an antisemitic conspiracy? Dr. Oppenheimer’s two main opponents — Dr. Edward Teller and Admiral Lewis Strauss — were they not also Jews, same as Oppenheimer?”

Zalowitz devoted a series of articles to unpacking the yiddishkeit of these three characters. Teller, Zalowitz offered, grew up amid the antisemitism of his native Hungary and was a “freethinking Jew” like Oppenheimer. Strauss, active in Jewish organizations and an interdenominational patron, was a proponent of the Reform movement and a firm believer in ethical monotheism.

Strauss once said that Jews “are witnesses to the principal discovery made by man — a discovery which dwarfs the greatest findings of modern giants of science — the discovery of the fact of the oneness of the Creator and all that has grown out of that revelation.”

Oppenheimer’s Jewish background was more remote and informed by the ecumenical humanism of his Ethical Culture education.

Toward the end of his life, Oppenheimer spoke about his feeling of “responsibility” for his role in the atomic age. When Look magazine writer Thomas B.. Morgan, interviewing Oppenheimer at the Institute in December 1966, said he spoke of “responsibility” in an almost religious manner, Oppenheimer replied that it was a “secular device for using a religious notion without attaching it to a transcendent being. I like to use the word ‘ethical’ here.”

High-minded ethics

“I think he was really high-minded in an ethical sense, and he’s very much a product of Ethical Culture Society,” said Bird. “Initially as a scientist as a young man encountering quantum physics in the 1920s, he was areligious and apolitical, but there’s also I think a deep humaneness about him. He is extremely empathetic.”

This empathy, Bird said, might count as a “strong religious identity,” even if it wasn’t traditional Judaism.

That’s not to say that Oppenheimer never thought of his heritage. He was self-conscious about his last name — and his father’s job in the garment industry — when he was a teenager visiting New Mexico. As a professor at UC Berkeley, when fascism reared its head in Spain and Germany, Oppenheimer’s concern for Jews partially paved the way for the political affiliations that would one day see him disgraced.

“By the late ’30s, he’s increasingly aware of his Jewishness in opposition to the rise of fascism,” said Bird. “And his only major motivation for building the gadget [the nickname for the bomb] was his knowledge that the German physicists he had worked with, studied under, like Heisenberg, were perfectly capable of understanding fission and its possibilities for a weapon. And he feared that the Germans were 18 months ahead.”

The refugee crisis grows

In the middle of the war, the United States physics community was terrified that German physicist Werner Heisenberg had a head start on the atom bomb. But Americans still had an advantage.

“We’ve got one hope,” Cillian Murphy, as Oppenheimer, says in the film, “antisemitism.”

Quantum physics, Oppenheimer explains to Lt. General Leslie Groves, was known as “Jewish physics.” Heisenberg’s development was hobbled by Hitler’s hatred, depriving him of some of the field’s best minds. Germany’s loss was America’s gain.

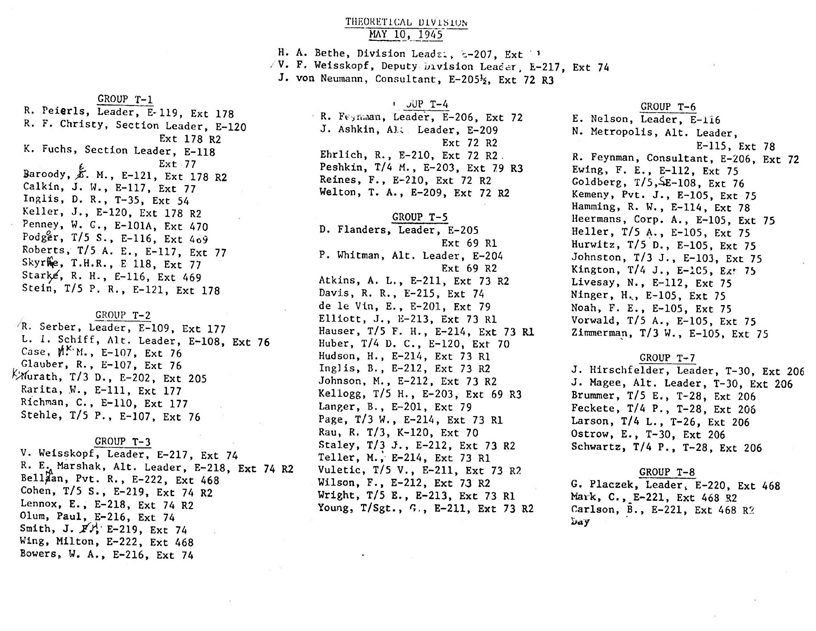

When Jack Shlachter, who has worked as a physicist since the ’70s and a rabbi since 1995, joined the Los Alamos National Laboratory’s Theoretical Division, he noticed the original roster from 1945 on an office wall. The sheer number of bold-faced names struck him. Then he noticed something else: “a lot of these people are probably Jewish.”

None were particularly observant, but many arrived at the lab as refugees from antisemitism.

“The saga of Los Alamos is it’s Jews from all walks of life, but it definitely included people who had fled Europe,” said Shlachter, who led T Division and serves as rabbi for the Los Alamos Jewish Center.

Oppenheimer knew the plight of his colleagues abroad, earmarking 3% of his teaching salary to help them escape, in between his donations to left-wing causes.

Like many Jews of means in the 1930s and ’40s, both Oppenheimer and Strauss worked to bring over refugees. In addition to helping physicists, Oppenheimer sponsored relatives and a family, the Meyerses, whom he didn’t know, and who he found time to write in 1944 while in a race to complete the bomb.

The refugee crisis occupied much of Strauss’ time. At the American Jewish Historical Society, where Strauss’ papers occupy 76 boxes, you can find meeting minutes for aid organizations, letters of thanks for his contributions to the United Jewish Appeal and folders full of documents from people seeking affidavits to escape Europe. Quite a few of the pleas were handwritten in German.

Strauss didn’t answer everyone who wrote to him for help, but he did respond when he could and kept their letters. Often he expressed deep sympathy but regretted that “I have received so many similar requests that were I to accede to them it would exhaust my means.”

In his 1962 autobiography, Men and Decisions, Strauss recalls attending meetings in London on the growing refugee crisis in a chapter titled De Profundis, whose Hebrew epigraph is from Psalm 130. Following a lament for “6 million human beings, of all ages and conditions, from old people already at the grave’s edge to the youngest and most innocent,” Strauss upbraids himself for not having done enough.

‘I had a continuing, smoldering fury’

“The years from 1933 to the outbreak of World War II will ever be a nightmare to me, and the puny efforts I made to alleviate the tragedies were utter failures, save a few individual cases — pitifully few,” Strauss wrote.”I might have done so much more than I did. I risked only what I thought I could afford. That was not the test which should have been applied, and it is my eternal regret.”

While Strauss’ public persona exuded Jewishness, Oppenheimer made just one oblique reference to his heritage in the autobiography he prepared for his security clearance hearing.

“I had a continuing, smoldering fury about the treatment of Jews in Germany,” Oppenheimer wrote in his letter to the AEC, explaining his political awakening. “I had relatives there, and was later to help in extricating them and bringing them to this country.”

In Nolan’s film, Oppenheimer is outraged when his colleague E.O. Lawrence implies he doesn’t know what’s at stake if the Germans have the bomb. “It’s not your people they’re herding into camps,” he tells Lawrence, “it’s mine.” Bird noted that Polish-born physicist Bernard Peters, who was interned at Dachau in 1933, shocked Oppenheimer with stories of his experience. The Nazi threat was not theoretical — it was personal.

Hitler’s rise to power drove both Strauss and Oppenheimer, but on different ends of the political spectrum. Oppenheimer once confirmed to Manhattan Project head of security John Lansdale that he was in “just about” every Communist front organization on the West Coast in the 1930s. As for Strauss?

“I’m not gonna say he is a member of more Jewish organizations than any historical figure I’ve ever seen,” said Gemma Birnbaum, executive director of the American Jewish Historical Society, “but he’s up there.”

Strauss, well-positioned in the realms of government and finance as well as the Navy, used his sway to help Jews abroad and to combat antisemitism at home. Birnbaum believes his extensive memberships in groups like the American Jewish Committee and American Joint Distribution Committee may have been his reaction to the genteel antisemitism of the circles he moved in — including the Hoover, Roosevelt and Truman White Houses and the military.

Strauss’ advocacy didn’t begin in the 1930s. When he was 22, working for Herbert Hoover’s food relief program in Europe, he heard news of the 1919 Pinsk massacre, in which a Polish commander murdered 35 Jews. Strauss met with the Polish prime minister and arranged for U.S. Army officers to keep an eye on Poland. Strauss wrote to Justice Louis Brandeis about these developments. The letter was later circulated to senators during Strauss’ confirmation hearing, “on the basis,” he wrote, “of a charge that I had used my position improperly to aid my coreligionists.”

But Strauss insisted that antisemitism played no role in the Senate’s 49-46 decision to reject him for secretary of commerce (he was then only the eighth cabinet appointment rejected in American history).

A seething resentment

“I have not the slightest reason to believe that the fact of the faith to which I was born or my affiliations influenced the vote of any Senator,” Strauss wrote. Instead, he blamed advocates of electric power, his belief in the separation of powers, his stubbornness, the Democratic opposition and, buried in the paragraph, “the animosity engendered by the Oppenheimer case.”

In the film, there can be no doubt that his persecution of Oppenheimer, prompted by vindictiveness and seething resentment, led to his undoing. Like many conservative Jews, Strauss also seemed to object to Oppenheimer’s left-wing entanglements, an alternative dogma to the Jewish faith. Strauss was particularly sensitive to the optics of Jews as Communists, answering scurrilous charges that his firm, Kuhn, Loeb & Co., had a role in financing the Bolsheviks in 1917.

In public, Strauss denied bad blood between himself and Oppenheimer, or that he was the driving force behind his hearing. “There were no personal animosities,” he wrote about their pivotal disagreement over the hydrogen bomb. He explained that his choice to vote against Oppenheimer’s clearance in 1954, when, in 1947, he approved him with much of the same information, came down to the revelation that Oppenheimer kept contact with a Communist friend, Haakon Chevalier, who approached him about sharing research with the Soviets in 1943.

Putting himself above the feud, Strauss wrote in Men and Decisions that he gladly reinstated Oppenheimer as director of the Institute for Advanced Study in the aftermath of the hearing. But it was under duress.

“He faced a virtual rebellion of people threatening to resign if Oppie was dismissed,” said Bird.

Oppenheimer’s undoing

Even after he’d taken a hatchet to Oppenheimer’s reputation, Strauss was still preoccupied with him in his duties at the Institute.

“He cannot tell the truth,” he wrote in 1955, about a minor financial dispute. Money came up before, with the self-made Strauss suggesting that the well-t0-do Oppenheimer could pay his own legal fees — rather than having the Institute foot the bill.

In Oppenheimer, Strauss’ hostility is grounded in insecurity. He thinks the Senate is trying to put the “lowly shoe salesman” back in his place by denying him a cabinet position. On the AEC, he bristles over the way scientists “resent anyone who questions their judgment.” There’s also a philosophical concern: Strauss can’t stand that Oppenheimer, after unleashing the bomb, would suddenly want to “put the nuclear genie back in the bottle.” Seeing the world in black and white, Strauss is convinced Oppenheimer’s newfound guilt is not only inconsistent, but insincere.

“I gave him exactly what he wanted,” Downey Jr., as Strauss, glowers in a recess from his own public humiliation in 1959, “to be remembered for Trinity, not Hiroshima, not for Nagasaki … he should be thanking me.”

There were no winners

“I think both of these men, ultimately, even though they vehemently disagree with each other, about many things, are coming from the same place, which is the greater good for the world and the United States,” said Birnbaum. “When you only look at his relationship with this one individual, with Oppenheimer, you get a kind of skewed view. It all gets erased into this one rivalry.”

“In the end they both suffered,” said Shlachter, “It’s sort of a tragic story all the way around, that people clashed and everybody lost as a result.”

Oppenheimer was redeemed in the end. His clearance was posthumously restored in December 2022. Is Strauss also due for a reevaluation?

“Surely, he plays the evil antagonist, particularly in the film,” Bird said, but applauded the nuance of Robert Downey Jr.’s performance. “His insecurity as Downey plays him is, I think, right on the mark. That explains his animus against Oppenheimer, who just fed all of Strauss’ insecurities. In a way you can come away from both the book and the film feeling a little sorry for Strauss because he’s not dumb. He’s an intelligent man; he’s trying to do good.”

A martyr to the Red Scare, and an unexpected patron

Strauss, through his obsession, ended up being defined by his feud with Oppenheimer. He also secured Oppenheimer’s legacy as a martyr to the Red Scare. Though Strauss was a prolific Jewish philanthropist and member of Jewish organizations, his Forverts obituary, which ran three short paragraphs, makes no mention of his involvement with Jewish life, writing instead that “one of his first steps as chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission was to start an investigation that led to the removal of Robert Oppenheimer due to ‘security motives.’”

His brief obituary from the Jewish Telegraph Agency mentions his Jewish associations as a kind of afterthought, after his post with the AEC.

But Strauss’ other activities weren’t entirely forgotten. When he died in 1974, a member of a small temple suggested something be done to honor Strauss, who helped secure an interest-free loan for the congregation’s building in 1960. The board passed a motion to donate books to the library in his memory, note his death in the temple bulletin and send a letter from the congregation to the admiral’s family.

The letter to Strauss’ widow called him “a great friend of our community.”

The community is the Los Alamos Jewish Center. Many of its congregants work at the lab Oppenheimer started and where, Shlachter said, he remains “God with a lowercase g.”

Translation and additional research by Chana Pollack.