John Garfield and Paul Newman could have been contenders in ‘On the Waterfront’

A new book on Elia Kazan’s 1954 classic suggests the film that might have been — without Brando

On the Waterfront might have looked very different had Budd Schulberg or Elia Kazan gotten their way. Photo by Wikimedia Commons

Few outfits in film are as instantly iconic as Marlon Brando’s plaid jacket in On the Waterfront, but Brando wasn’t always the first choice to fill it.

Film journalist Stephen Rebello’s A City Full of Hawks: On the Waterfront Seventy Years Later–Still the Great American Contender chronicles the turbulent production of Elia Kazan’s classic film and the many different paths it might have taken. On the matter of casting, Rebello informs us there were other contenders for the top of the call sheet.

When Budd Schulberg started what would become On the Waterfront, initially just titled Waterfront, he wrote the part of Terry Malloy, a would-be boxing champ-turned-longshoreman and informant, with a different star in mind: John Garfield (né Jacob Julius Garfinkle).

Kazan had worked with Garfield in the past, notably in Gentleman’s Agreement, the Oscar-winning expose of American antisemitism. Rebello notes that Garfield was also the producers’ pick to play Stanley Kowalski on Broadway in Kazan’s production of A Streetcar Named Desire, the part that made Brando famous in the first place.

How different would cinema look had Garfield played the signature roles in Brando’s stead? It was not to be. Garfield, who refused to name names before the House Un-American Activities Committee, was spared the irony of acting in a film about an informer, written and directed by men who named names (Rebello calls Schulberg and Kazan “among HUAC’s friendliest of friendly witnesses.”)

Garfield was blacklisted starting in 1951 and, in May 1952, a month after Kazan’s infamous testimony, he was dead at 39. The cause, reported as a heart attack, is often attributed to another cause: stress from McCarthyism.

Newman’s Own and Miller Time

Brando wasn’t Kazan’s preferred choice for Waterfront. Or, rather, he knew that Brando was resistant to the idea of working for him after he informed.

“If we don’t get Brando, and I think it most likely we won’t, I’m for Paul Newman,” Kazan wrote in a July 1953 letter to Schulberg. “He’s just as good looking as Brando and his masculinity which is strong is also more actual. He’s not as good an actor as Brando yet, and probably will never be. But he’s a darn good actor with plenty of power, plenty of insides, plenty of sex. He and [Karl] Malden are working on two scenes to show to Sam and yourself. I’m for him without seeing more.”

In 1953, Newman was a new talent breaking through in William Inge’s play Picnic. The scenes he rehearsed with Malden were from Jewish Hungarian playwright Ferenc Molnár’s Liliom, the basis for Rodgers and Hammerstein’s Carousel. Newman was acting opposite his Picnic costar Joanne Woodward. How the love scenes contributed to their affair and ultimate marriage is Hollywood history.

So too is The Hook, a separate, unrelated film about crime on the waterfront penned by Arthur Miller that was being developed at the same time as Schulberg’s project.

Schulberg, a dynastic Jewish talent in Hollywood, who, with his brother, Stuart, collected film evidence of Nazi horrors for the Nuremberg trial, embedded with stevedores for Waterfront off a film option for a New York Sun series of articles. Miller came to the material separately, having spent a lot of time in Red Hook, Brooklyn. His screenplay was inspired by the 1939 disappearance of the dockworker Pietro “Pete” Panto.

Kazan and Miller’s relationship — and their collaboration on The Hook — would break down following Kazan’s HUAC testimony, and Miller would rework The Hook into his play A View from the Bridge, about a dock worker who blows the whistle to immigration authorities on his wife’s cousins from Italy. (Miller biographer John Lahr has posited that the play is speaking “across the footlights to Kazan.”)

That Kazan was involved in an earlier waterfront project — one that Hollywood feared, baselessly, was “pro-Communist” — would be largely incidental to Hollywood lore, were it not for what he and Miller got up to at the time of their collaboration.

Waiting to hear from executives, Kazan took Miller to a soundstage where they saw a young actress named Marilyn Monroe. Kazan, Miller and Monroe soon had a Jules et Jim triangle going on, and the men even had her pose as Kazan’s temporary secretary in a meeting with Columbia for The Hook, “wearing an owlish pair of prop glasses and carrying a steno pad.”

One evening Kazan gave Miller Monroe’s number to be her date to a party (Kazan was busy working on “casting” Monroe’s friend Jean Peters in Viva Zapata). Party guests noted that Miller and Monroe were “totally wrapped up” in each other. By 1956 they’d be married.

A ‘schnorrer’ producer

The production of On the Waterfront was sometimes stymied by its constantly overleveraged producer, Sam Spiegel, an immigrant from Jarosław who the crew called “that Jew bastard” and who Brando dubbed a “schnorrer” and who screenwriter-director Gottfried Renhardt named a “congenital crook with a crook’s mentality.”

Spiegel had been imprisoned for fraud back in Europe but managed to escape ahead of the Nazis. (Spiegel quipped to a friend “so what if I lied? I would have been a bar of soap.”) He was, despite his many failings, a man with a great eye for stories.

The success of Waterfront was due to Spiegel’s advocacy and his pocket book — even if he often proved a pest on set, insisting Kazan finish his shooting days quicker.

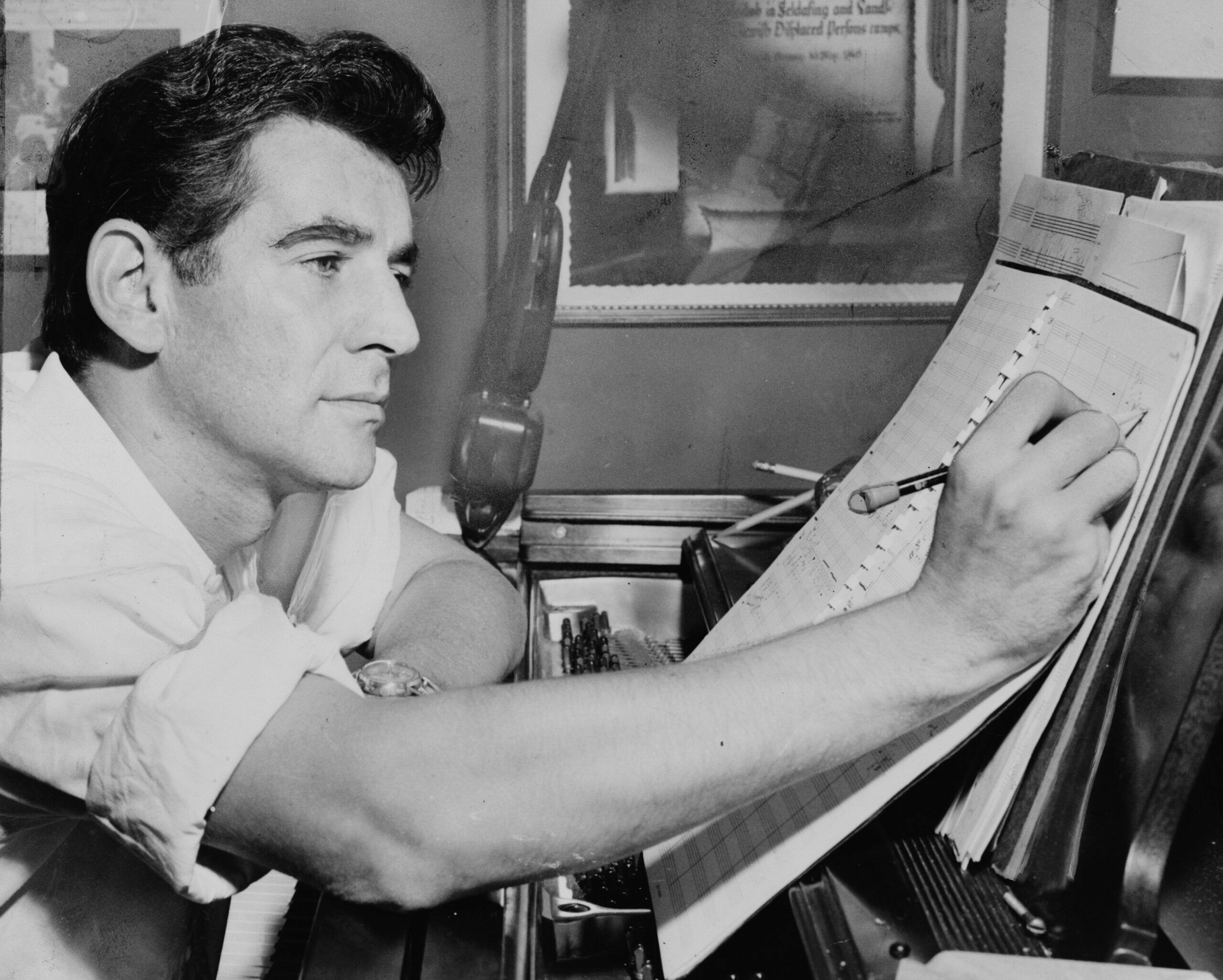

Bernstein plays the stevedore blues

Of special interest to fans of Leonard Bernstein, Rebello relates how the maestro, who came to detest scoring film, was ultimately won over by a rough cut of On the Waterfront. (We also learn he did a screen test to play Tchaikovsky in a biopic scripted by Ayn Rand, which his sister, Shirley, recalled being “terribly written” and his performance no better.)

When Spiegel approached him, Bernstein was working on a number of projects, including a TV opera about David and King Saul and an Eva Peron opera with Lilian Hellman, decades before Evita. None of those would materialize, but Bernstein was excited by the film and Brando’s performance, recalling in his autobiography The Joy of Music how he was “swept by enthusiasm into accepting the commission to write the score.”

That Spiegel courted Bernstein, who had a lengthy FBI file, is a testament to his star power in the 1950s. Rebello says Bernstein’s score anticipates his later work in West Side Story and you can even hear him play piano in the soundtrack (he got $48.21 union scale).

Bernstein ultimately felt burned by the way Kazan cut his music, often breaking it off mid-phrase, and wrote an article for The New York Times to say as much. Regardless, the film is an indelible classic, and the score is no small part of its endurance.

The sequel that never was

Rebello’s account of Waterfront doesn’t stop at the 1955 Academy Awards, when the film collected eight Oscars. It gives a hint of a story to be continued, letting readers know that in the 1990s Schulberg penned a sequel, Back on the Waterfront, which revisits the Hoboken docks through the eyes of Terry Malloy’s son.

In the screenplay, Karl Malden’s Father Barry does something interesting: uses the Yiddish word “shtarker.”

It just goes to show: you can take the Jews out of the frame, but their contributions stay in the picture.