How a beloved TV detective embodies a central Jewish value

When a man liked my ‘Columbo’ hat, I realized the power of the follow-up question

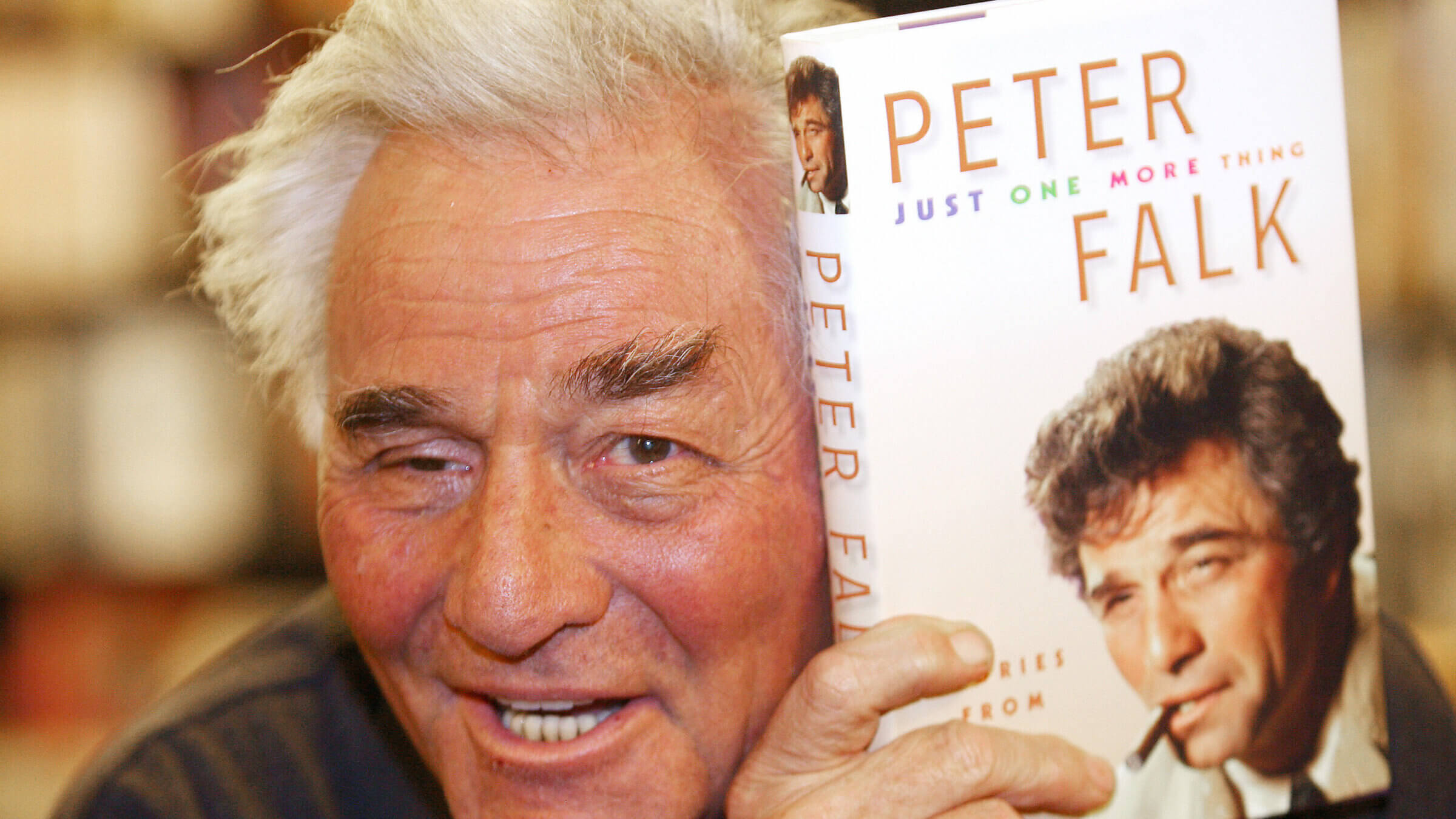

Peter Falk poses with his memoir, which was, naturally, titled Just One More Thing. Photo by Gabriel Bouys/AFP via Getty Images

I went to the first day of the U.S. Open’s Fan Week on Monday — it would be fair to say I wasn’t exactly the target demo.

While crowds amassed in Flushing, setting necks to oscillate as balls whipped by in qualifying matches, my girlfriend was walking me through what “deuce” means. The uniform for most observers was Ralph Lauren; I was wearing a khaki baseball cap stitched with the name “Columbo.” I identify more as a fan of Columbo, the disheveled TV sleuth played by Peter Falk, than Coco Gauff.

A man snapping photos with an expensive-looking camera tapped me on the shoulder and, in an unplaceable-to-me accent, complimented my hat.

He walked away but soon returned to tell me “one other thing.” I waited for that thing, but then he clarified: “That’s a joke.”

Indeed, it’s on the back of my hat, “just one more thing” being as close as Lieutenant Columbo had to a catchphrase. Within that further request is an entire Jewish ethic.

Back up. Is Columbo, the long-running NBC (later ABC) “howcatchem,” now available to stream on Peacock and Tubi, a Jewish show?

It was created by Richard Levinson and William Link, the latter of whom only found out well after the show ended that he was Jewish, though the clues were there.

Steven Spielberg directed the first non-pilot episode.

Falk, the man who was Columbo, was born in the Bronx to a dry goods merchant.

You can tell the players with a scorecard (the show’s composers include Billy Goldenberg and, in one episode, Stephen Sondheim’s regular orchestrator Jonathan Tunick), but that in itself may not make a show Jewish.

Columbo the character is ostensibly Italian — his first name, erroneously listed as Philip in a 1981 edition of Trivial Pursuit, is supposedly “Frank,” if one zooms in on his badge in a couple of the episodes. He was christened by propmen, not his creators. He is primarily a cipher, married to a Mrs. Columbo — “Kate” in a short-lived spinoff in which he never appeared — the owner of a dog named “Dog.”

In his way, he is like the prophet Elijah, flitting in and out of lives. Written off as an inept nuisance by a gallery of guest star murderers, he is underestimated and unheeded like Jeremiah. He’s perennially out of place, looking like he emerged from a spin cycle to nose around the tony homes of art collectors, maestros and architects.

But the key to his Jewishness is his line of questioning.

With Columbo, there’s always another thing before he leaves the room. When he asks a suspect to explain some inconsistency, he typically knows the answer, and the perps usually realize their alibi is shot.

We’re not all Columbo, but there’s something undeniably Jewish about the follow-up question.

We see it in prophetic challenges to God, the four questions in the Haggadah, the dynamic debates in the Yeshiva hall between havruta partners. (One can almost imagine Detective Columbo, rumpled raincoat swapped for a kapota, squinting and rubbing his brow as he challenges this or that tractate.)

The Columbo approach to life, endlessly curious, detail-oriented, committed to putting a messy world in order, is the work of detectives, journalists and Jews, each of which have an unfair reputation for being unpleasant interlopers.

If I felt that way at the Open — peppering my girlfriend with questions like: “Why does the score jump from 15 to 30, but then to 40?” “What’s that weird vest thing Taylor Fritz is wearing?” and, most importantly, “Is Waluigi playing?” — then it was a comfort to know Columbo was similarly inquisitive in the 1990 TV movie Murder in Malibu

In that adventure, the culprit is absent at a celebrity tennis tournament. Columbo proves his guilt by way of adjusting women’s underwear on a mannequin. Don’t ask. Or, actually, do what Columbo would, and ask away.