Judd Apatow on why Mel Brooks’ influence ‘will last as long as our jokes’

Apatow and Michael Bonfiglio, directors of the new HBO documentary on Brooks, talk about his legacy of laughter

Mel Brooks sat down for 10 hours of interview with Judd Apatow. Courtesy of HBO Max

“May you live to 120” is a common Jewish blessing. This is the ideal age, the precedent set by Moses. A corresponding curse — some say it’s Chinese, but it feels palpably Yiddish — is “may you live in interesting times.”

At 99, Mel Brooks is still short of Mosaic longevity, but has undeniably lived, like his 2,000-year-old man, through interesting times. Often, he was the one who kept things interesting.

Into the whirl of the Brooksissance — an epoch witnessing a streaming sequel to History of the World Part I, the forthcoming Spaceballs II and a just-announced series Very Young Frankenstein — comes Mel Brooks: The 99-Year-Old Man! a two-part HBO documentary co-directed by Judd Apatow and Michael Bonfiglio. It is a deft portrait of the entertainer that earns its prodigious length. (Unlike a Brooks sequel, you won’t have to wait decades for the second installment — you can stream both starting Jan. 22.)

Structured around recent interviews with the comedian, and surfacing a wealth of rarely seen archival footage, the documentary distinguishes itself from previous efforts, like a 2013 American Masters episode, by going deep on Mel the man.

“Slowly he opened up and was willing to have that deep a conversation,” Apatow told me in an interview.

Apatow and Bonfiglio’s film addresses Brooks’ first marriage, his imposter syndrome and how his insomnia and chronic lateness on Your Show of Shows may have stemmed from PTSD from World War II, where he dug through German soil with a bayonet hunting for unexploded ordnance.

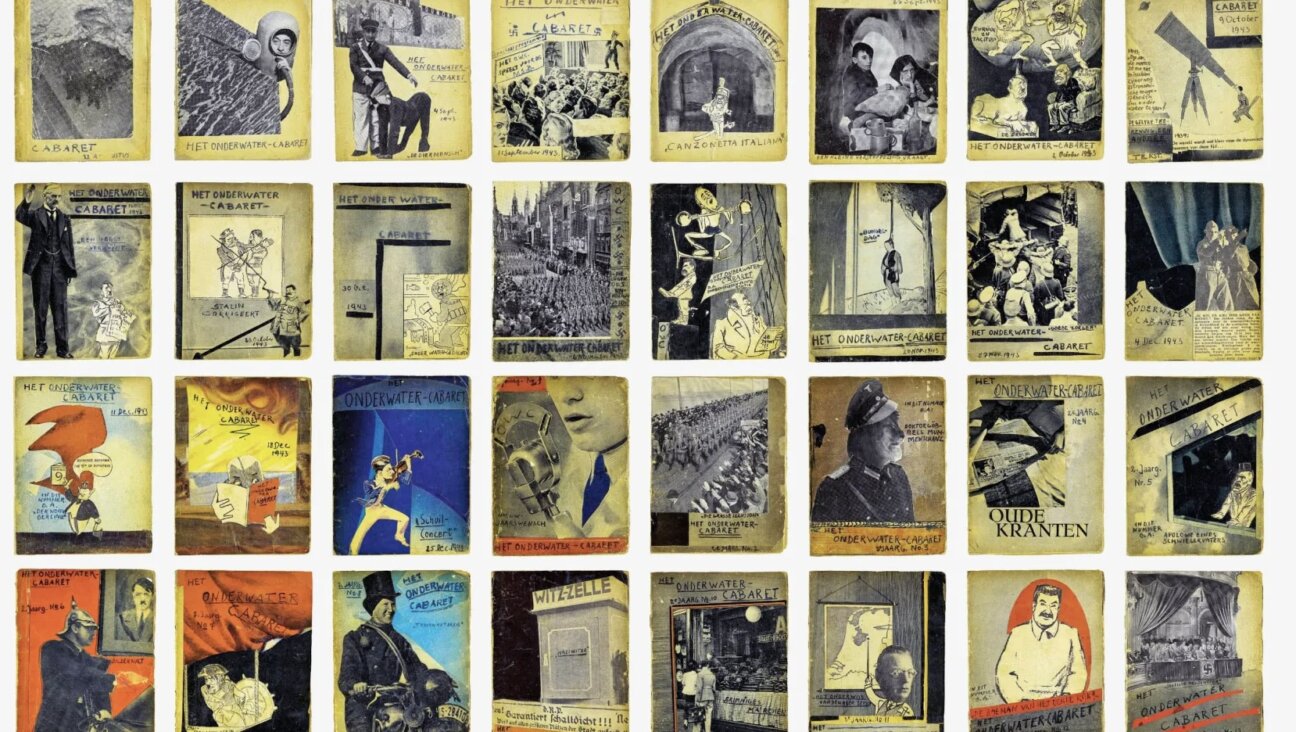

The film even explores a now quaint-seeming controversy over the Inquisition musical number from History of the World Part I (the St. Louis Jewish Light slammed him for indulging in “the kind of humor which would have received a standing ovation from an audience of stormtroopers and concentration camp commanders.”)

The documentary features interviews from across the world of comedy — perhaps the last occasion you’ll see Dave Chappelle and Jerry Seinfeld sharing a bill — including the bittersweet, invaluable insights of the late Rob Reiner.

“Fear is the main motivator for what he does,” noted Reiner, who also recounted Brooks’ heartbreak when Rob’s father, Carl, died. “The fear of not being funny, the fear of not being liked, whatever the fear is.. and because of that he becomes a lovable person.”

I spoke with Apatow and Bonfiglio about how one interviews a living legend, how Brooks’ example teaches us how to take on tyrants, and the surprising environmental message the auteur smuggled into Spaceballs. The following conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Mel Brooks has been interviewed a lot, as we can see in the film — Judd, you even interviewed him for the Atlantic a couple years ago — but he told you that he doesn’t think people know the real him. How did you go about trying to get past the persona?

Judd Apatow: He’s been a private man throughout his life. When he’s been public, he likes to tell the old stories, and anecdotes. It’s funny because an old friend of Mel’s said to me, “You know, all his stories are bullshit. They’re all bullshit. They’re all made up.” And so in one of the interviews I said, “Mel, are any of these stories true?” And he goes “No!” So we’ll never know for some of it — the legends of Sid Caesar holding writers out the window — ‘cause he’s one of the great raconteurs. But I thought it would be really great to approach this as a person who does what he does, who has a life that is in some ways similar to his and to say, “What happened and how did you do it? How did it feel — what lessons can I learn from you?” And slowly he opened up and was willing to have that deep a conversation.

One of the great pleasures of this is the archive — him with Sid Caesar and the writers, outtakes of the Ballantine’s beer ad, behind-the-scenes footage — Michael, what was it like diving through that material. Was there anything that stands out as great or rare?

Michael Bonfiglio: It was so much fun. Mel has so many great stories, and when you go back through all the talk shows and stuff you notice he tends to tell the same one in different venues. Which we had a bit of fun with in the edit as well. We were always kind of looking for things where we said, “Oh, I haven’t heard him say that before, or talk about that in that way.” Some of those came from interviews we found on European television that we got from archives that probably have not been seen since they were on television and, sometimes he would be in a slightly different mode, maybe because it was a different audience.

There’s an interview where he’s talking about Spaceballs, and how air was the commodity in Spaceballs because the world was run by people who didn’t care about the environment. And it was like, “Oh, that’s not really something I got out of Spaceballs, but was clearly on Mel’s mind.” It was interesting to see how in Silent Movie how to him that was a commentary on media consolidation. Those ideas are there and I think those can be the comedic engine, as he would say, behind some of these films.

Apatow: Silent Movie was The Studio of its time.

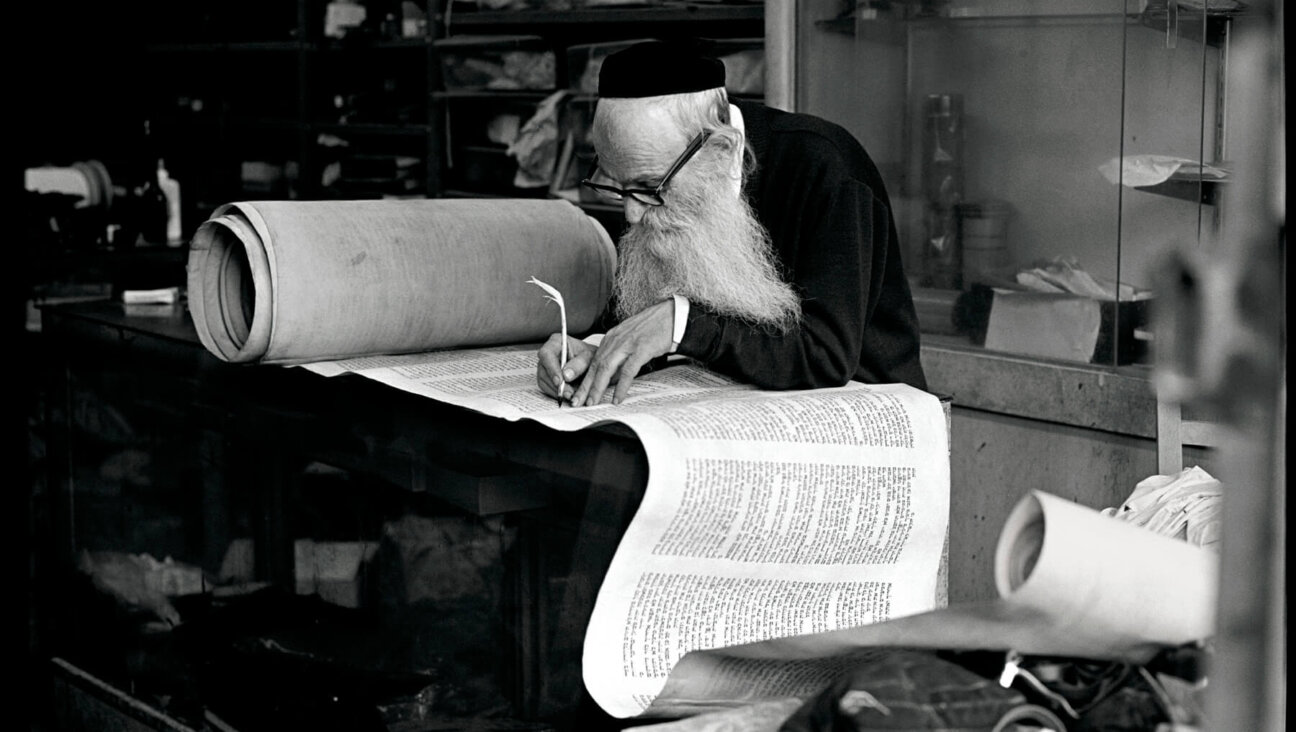

Brooks wrote in his memoir “for the most part to characterize my humor as being purely Jewish humor is not accurate. It’s really New York humor.” What do you make of that assessment and how, to you, does the work seems Jewish?

Apatow: I’ve never known what defines Jewish humor enough to break it down. What is the difference between Jewish humor and the stuff Mark Twain was doing? Obviously you can say there’s humor that comes out of suffering. Joyous, brash humor that you tell because circumstances are so difficult. I’ve never been good at intellectualizing comedy. I always feel like comedy dies on the operating table. Mel, I think, is very proud of the fact that it works for everybody, so I’m sure for him he’s not trying to be specific in that way — but he may be doing it anyway. I don’t think of myself as someone working from a Jewish perspective, but clearly I am, whether I know it or like it or not!

I think it’s maybe reflexive for him. Even if he says it’s New York humor, growing up in Williamsburg everybody was Jewish!

Apatow: That’s his New York!

There’s a whole section about Brooks taking on Hitler. Judd, recently, very publicly, you suggested we’re living in a dictatorship. What can we learn from his example of making fun of autocrats?

Apatow: I think he fought in World War II and fought against authoritarianism and he felt it was important to speak truth to power. That’s why they attacked the Jimmy Kimmels and Stephen Colberts of the world. And I think we should all be inspired by his willingness to speak up. There are bad things happening right now. It shouldn’t be that shocking to say we’re living in a dictatorship. We don’t have a legislature that does anything. I think everybody should speak up, and everyone should be allowed to make fun of it ‘cause that’s why we’re in this country: for our freedom of speech.

On the question of legacy — he did so much. We didn’t even get into the short film The Critic, the first time the Academy recognized him. What do you think his legacy will be?

Bonfiglio: Laughter. Big, big laughter and I think that’s really what’s more important to him than all the awards and all of that, because I think that his work is gonna live on. It has. Blazing Saddles and Young Frankenstein are over 50 years old now and they’re still hilarious. The comedy and the joy will live on.

Apatow: In addition to being as funny as anyone who’s ever been on Earth, he also gave a lot of people opportunities through his writing and directing. He introduced the world to people like Marty Feldman and Gene Wilder and Madeline Kahn and Teri Garr and on and on and on. There’s a real butterfly effect to all the people that went into comedy because they loved him, and so I think his influence will last as long as our jokes.