There’s something so Jewish about how very un-Jewish Stephen Sondheim was

A conversation with DT Max, the author of ‘Finale: Late Conversations With Stephen Sondheim’

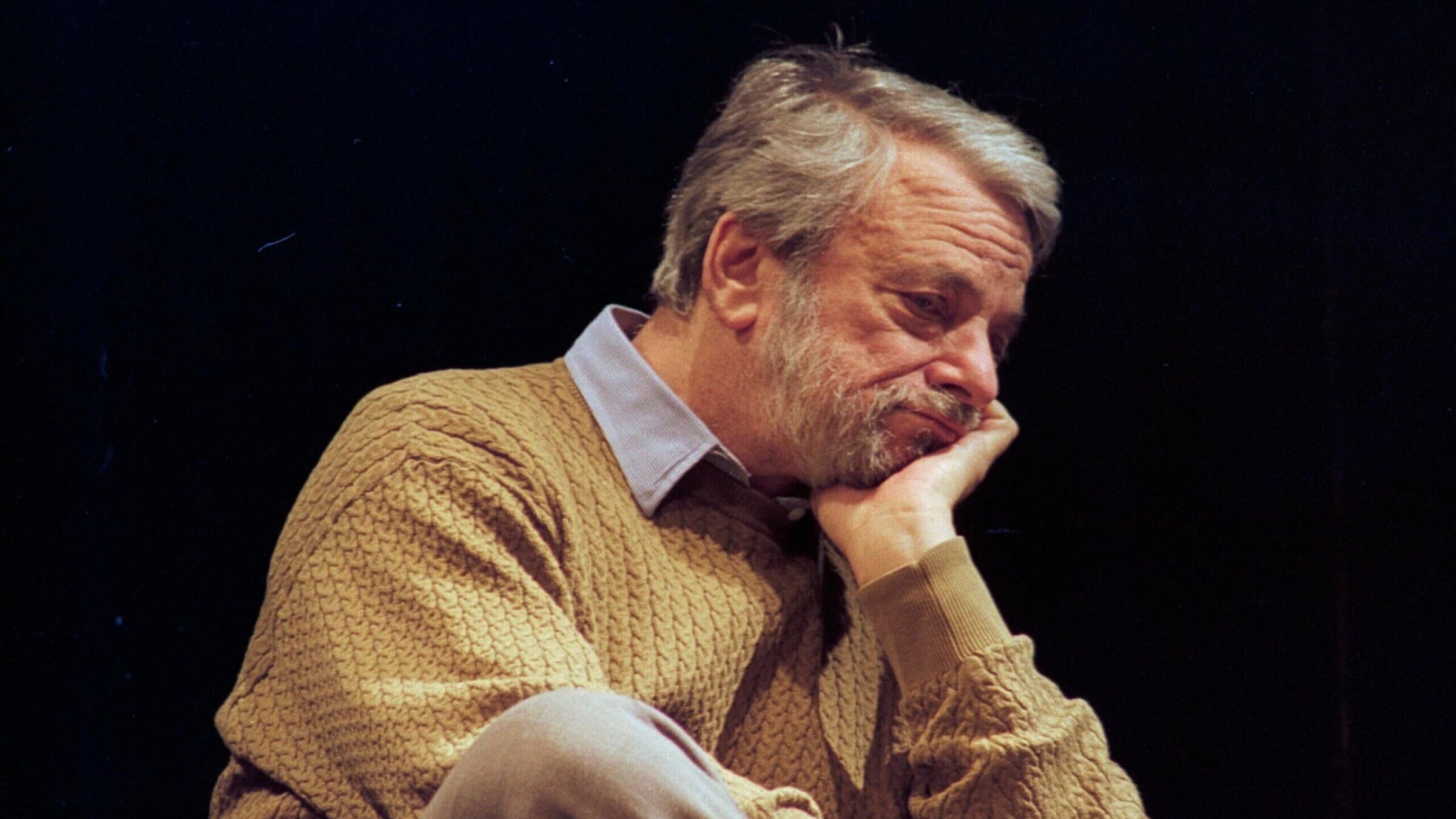

Stephen Sondheim in East Lansing, Michigan, 1997. Photo by Getty Images

In the years leading up to Stephen Sondheim’s death, the writer D.T. Max began a series of interviews intended to culminate in a New Yorker profile of the composer to publish in conjunction with a new musical. The piece never manifested, because production on the musical stalled just before the onset of the pandemic, and then Sondheim died in November 2021, at the age of 91. Instead, Max has published the interviews as a collection titled “Finale: Late Conversations with Stephen Sondheim.” I spoke with Max about the book at the recently-overhauled Drama Bookshop. Our interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Sondheim was famously hesitant to open up in interviews. Did you feel like you got through to him?

I don’t think with somebody like Sondheim, you can realistically think you’re going to have some sort of moment where he suddenly goes, “I’ve been unable to tell anyone this my whole life.” But he does say things he’d never said before. I’d always been curious about what he actually felt or thought about being Jewish.

It seems like he really did not have any feelings.

Well, but those are feelings and thoughts themselves.

Did Sondheim ever write an explicitly Jewish character?

There is certainly no one who celebrates Shabbat. I mean, he’s not writing Fiddler on the Roof. I think he saw Jewishness as provincial. As did many Jews at the time. It was what they had escaped.

Especially being sort of assimilated into the upper-middle class.

And working very hard to stay that way. You know, he goes to college in one of the most antisemitic eras ever. All these colleges, including [Sondheim’s alma mater] Williams, I’m sure, had a quota. He joins what I understand to be a very WASP-y fraternity. I’m getting this from the Meryle Secrest biography — he says to her, “oh, there were no issues. It was all fun.”

And you’re like, come on! You’re a gay male Jewish son of people in the garment industry. And you go to Williams, and you don’t find anyone who’s making you feel like an outsider? But that’s what he said. It seems so beyond belief.

There’s also that quote where he’s like, “antisemitism in musical theater? Name me three non-Jewish composers.”

That’s from the Abby Pogrebin interview in Tablet magazine.

It does seem like also he didn’t have too much of a connection to the religion itself. Actually, it seems like a lot of times he brought up Judaism, it was in relation to Leonard Bernstein. I sort of wondered if that relationship was the closest that he got to Jewish religion.

Bernstein did have a passover Seder. I mean, this gets into the conversation — there’s cultural Jewishness and religious Jewishness. I would argue that his work is quintessentially culturally Jewish.

How so?

It’s easier with the early stuff. Like, Merrily We Roll Along. The characters seem to be Jewish people. If you look at Company, you could argue the flaw that Bobby has is he doesn’t have any guilt. Sondheim says Bobby graduates into the world at the end of the musical, but he really graduates into a pretty stereotypically Jewish sensibility about guilt. You have to give back; you can’t just take from people. And even Into the Woods — the second act, there’s this whole blaming thing, right? It’s so Jewish. “He did it; no, he did it.”

His characters are often internally fraught; they’re trying to make decisions about their lives. How would you define Sondheim’s ethics?

If you think about the complexity of his harmonies and how they often don’t do what you expect, I feel like in a lot of ways, they’re telling you to look inside yourself and not to just do things on impulse or because it’s been done before. And although that sounds a little far-fetched, I actually don’t think it is when you really think about his music. Time and time again, something looks like it’s gonna break into a familiar melody or an easy-to-sing kind of thing. And then — whoa — you’re off in a different place.

To me, the most Jewish part of the interview was his description of his relationship with his mother. He seemed to feel … not especially warm toward her.

Absolutely batshit angry.

But then he also seemed not that interested in admitting that — he seemed to think he had moved past it.

Both he and I are excellent compartmentalizers, and when he did let go of this gust of emotion, I tried to talk him out of it. I said, “it’s like material for you now,” and he agreed, saying that was a very good way to put it. But I don’t think it really was just material for him.

The relationship sounds heartbreaking.

Yeah, and I think the way he pathologized it is itself heartbreaking.

And very Jewish.

Ha.

It makes me think of some of his mothers, like Mama Rose, who I don’t really think of as feeling very Jewish, but there’s a certain ferocity.

I would be nervous to engage in cliches about Jewish emotion or personality, because there’s truly so much variety, but the dominating Jewish mother cliche, yes, and the ambitious Jewish mother cliche —

Which is interesting, because I can’t think of any famous Jewish actresses that have played that part.

That’s interesting. One thing you have to remember is how much he wanted actors who sing.

I think that comes through in the way Sondheim talks about Chekhov. There’s a line I love where he talks about how Chekhov wrote for actors.

Silences. He’s big on the silences that surround text. Subtext.

For me, character is one of the things that Sondheim does best. I mean, I love musicals, but so many musical characters are wooden shells that are filled with belting, basically. And I feel like Sondheim’s characters are beautiful, full people.

Yeah. He mentions Chekhov a couple of times, actually.

Which is such an interesting influence for a musical theater composer.

Yeah.

I thought that the other most Jewish part of the interview was when you guys both talked about your physical ailments.

Well, now you’re indulging in cliches.

Ha.

A funny story, actually, is that if you watch old clips of him from shows in the ’50s, when he’s on with Richard Rodgers talking about Do I Hear a Waltz?, stuff like that — back then, he talks with a high, British-y accent. And by the time I see him, he’s talking like a wisecracking Damon Runyon character. So who is the original Sondheim?

Who is the authentic Sondheim? Right.

I really wanted to have conversations with him. The book pleases me, because it doesn’t make you think you have to have a certain opinion. It’s more like meeting a person. I meet you and I have some impressions this time. I might have some impressions next time. I spend a little bit of time thinking, how do I make these impressions cohere into my idea of a personality?

It feels sort of Sondheim-esque to not come to a conclusion.

That’s certainly the idea.