In a Romeo-and-Juliet musical set in WWII Shanghai, Chinese and Jewish refugees are star-crossed lovers

‘Émigré,’ a new production by the New York Philharmonic, recalls the city’s embrace of over 20,000 people fleeing the Holocaust

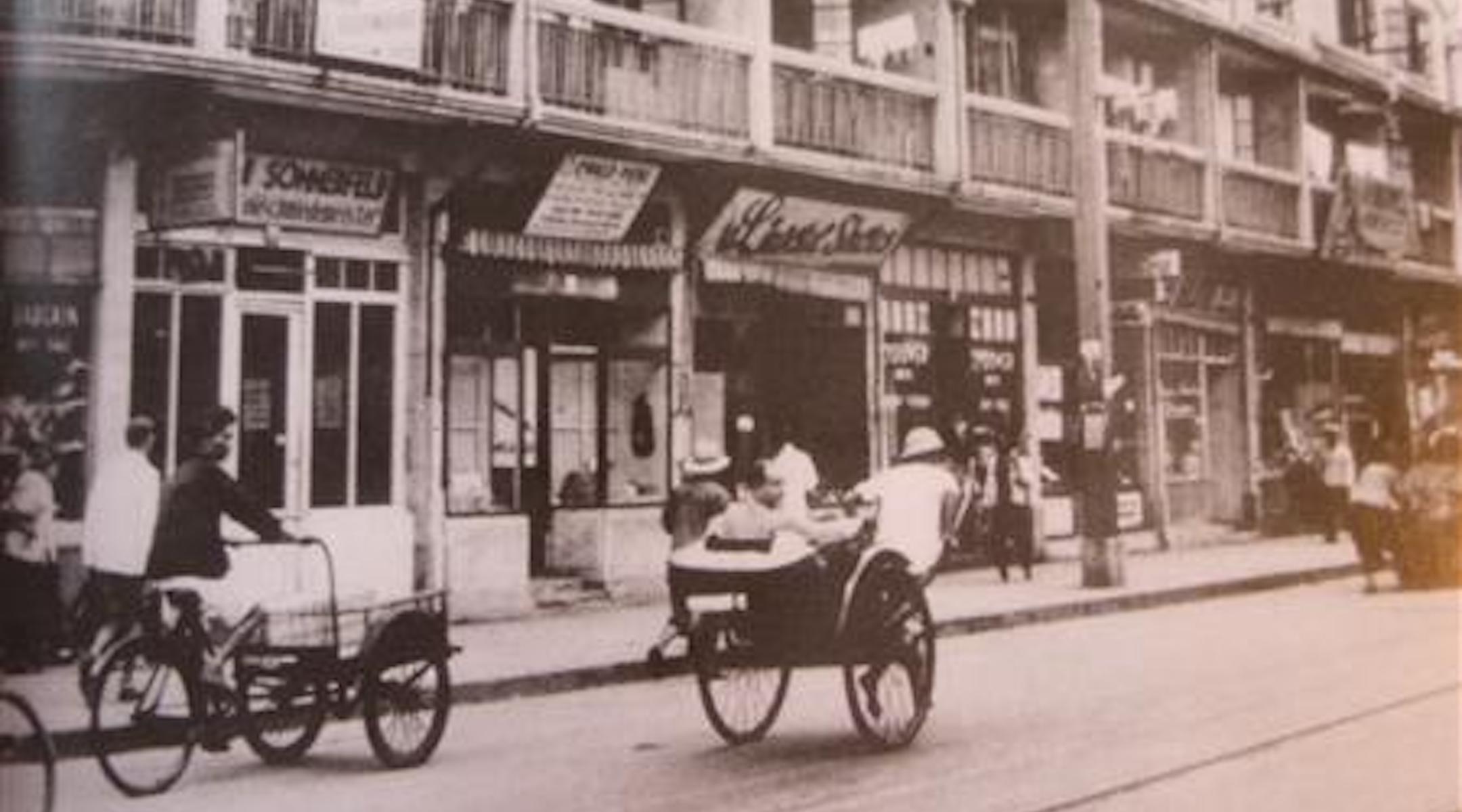

A street in the Shanghai Jewish Ghetto circa 1943. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

During World War II, while the United States limited immigration to the country and turned away a barge full of Jewish refugees, one port city kept its doors open to Europe’s persecuted Jews: Shanghai, China. From 1933 to 1941, Shanghai welcomed over 20,000 Jews fleeing the Holocaust.

Émigré, a new musical commissioned by the New York Philharmonic, the Shanghai Symphony Orchestra, and its musical director Long Yu, tells the story of star-crossed lovers, one Chinese and the other Jewish, who marry despite divisions between their people and a brutal war that is devastating both groups.

Shanghai, which had long been an international city controlled in part by foreign powers, was one of the few safe havens open to Jews. By the end of the war, though, the Japanese controlled the port city, and forced Jews into a one-square-mile ghetto that was rife with disease and poverty. Still, Jews found ways of maintaining their cultural life through music and theater, and many operated successful businesses and experienced kindness from their Chinese neighbors, despite their mistreatment by Japanese occupiers.

Long Yu, who originally conceived of the musical, said that he wanted to spread the word about Shanghai’s welcoming of Jewish immigrants because it highlights the “goodness and kindness of humanity” that emerges when people are in need. Yu, who leads the Shanghai Symphony Orchestra, grew up in Shanghai with a choreographer for a father and a pianist for a mother, part of a Chinese musical ecosystem that has long been influenced by Jewish artists. In the 1930s and 40s, Jewish artists who had taken refuge in Shanghai taught classical music to Chinese youth, launching the careers of artists who would go on to become professional musicians and play in China’s national orchestra.

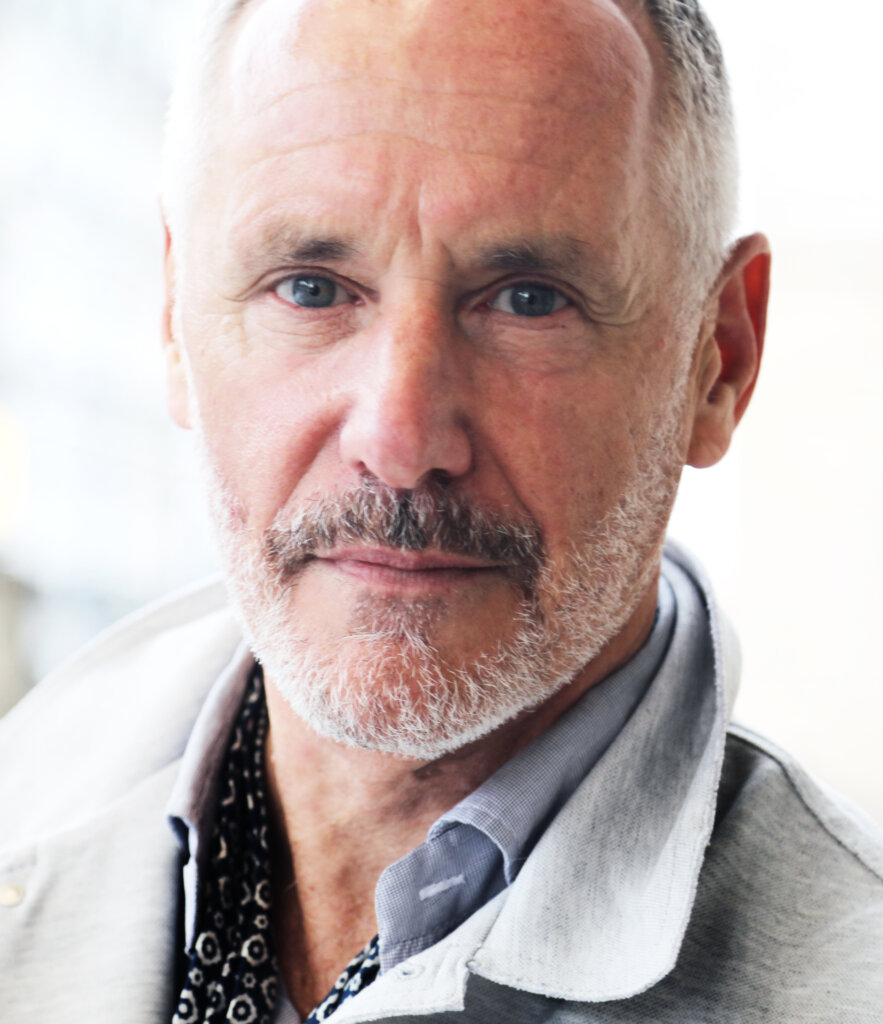

Yu has wanted to use music to tell the story of Jews in Shanghai for two decades, he said. This idea came to fruition when, after a 2019 performance at the New York Philharmonic, he met Aaron Zigman, a composer known for scoring films and TV shows such as The Notebook, Sex and the City, and Bridge to Terabithia. Yu asked Zigman if he would be interested in composing a musical about how Shanghai harbored Jews during World War II. “I couldn’t say no,” Zigman said. “I had too many, much too many, connections to this period of Holocaust.”

Zigman, who is Jewish, calls himself a “Holocaust freak” and said that he has been studying the Shoah since he was seven years old. He had been interested in the Jewish diaspora in Shanghai for a long time, in part because a man who he calls his “surrogate father” was a part of the Jewish diaspora there before moving to the United States.

In composing the musical, Zigman decided to create a love story “for the sake of staying out of politics,” he said. Mark Campbell and Brock Walsh wrote the lyrics, creating a story that is simultaneously an ode to cross-cultural friendship and a cautionary tale about the dangers of tribalism.

At the musical’s debut in Shanghai, logistical snags and financial limitations caused the musical to be performed in a minimalist manner, with singers performing without any background images. For the New York production, Director Mary Birnbaum leads a team that will design wall projections and the singer’s costumes, all based on extensive research into what life might have been like for Jews and Chinese at the time.

For Birnbaum, who has Jewish and Catholic heritage and was raised Quaker, the musical’s nuanced depiction of Jews’ relationships to Chinese people was particularly compelling. “I relate to mixed heritage entirely,” she said.

For the wall projections, Birnbaum chose a variety of displays that correspond to the differing perspectives that characters might have had on Shanghai. For source material, she turned to the work of Jewish artists who lived in Shanghai, like Peter Max, now known for his psychedelic pop art. Embroidery, a medium shared by Jewish and Chinese artists, features heavily in characters’ costumes, with some Jewish characters wearing embroidered images of family members left behind in Europe.

Meigui Zhang, the soprano playing Lina, the Chinese woman at the center of the story, said that she had never heard of the history of Shanghai’s Jews before working on Émigré, despite having gone to college in Shanghai. She hopes that people who learn about China’s kindness towards Jewish refugees will be inspired to help others.

The musical centers on the lives of two brothers, Otto and Josef, who escape Nazi Germany in the late 1930s, and the women, Tovah and Lina, with whom they fall in love. Otto, a rabbinical student, meets Tovah, the daughter of the Rabbi at the local yeshiva, while studying there. Josef, a young doctor, falls for Lina when he visits her family’s Chinese medicine shop. Lina’s family survived Japan’s massacre of civilians in Nanjing. In one scene, Lina and Josef both light candles for endangered or deceased family members, and Lina calls the two of them “shounan tongbao,” or “suffering comrades.”

Lina and Josef’s families reject their relationship, at one point joining forces to sing, “Our people,/ Should only be with our people,/ Our people,/ Should never stray.”

“It’s a smaller personal story about generations holding on to old ideas of boundaries, and not letting them go,” Campbell said. “And that produces a tragedy.”

As the Japanese and American bombing of the city intensifies, both families shut Lina and Josef out of their homes. Tovah pleads to her husband and father on their behalf, reminding them, “You’ve been there before.” She runs out of the house to help them, and she —along with, off-stage, Lina’s sister Li — is killed in an explosion, leaving Lina and Josef to persevere in the wake of their loss.

“That echoes to what is happening in the world all the time,” Campbell said. “As you hold on to these old ideas of how we have to separate ourselves from other people on this planet, then the planet will perish.”

In the four years since Yu approached Zigman about what would become Émigré, global politics have tested the capacities of China, the U.S., and the Jewish diaspora to transcend tribalism: the relationship between the U.S. and China has soured; sinophobia, antisemitism, and islamophobia are on the rise; Russia and Ukraine, and Israel and Palestine, are embroiled in wars that have killed thousands of civilians. But the Émigré team maintained that the political tensions surrounding their project didn’t influence their creative process, and that their job as artists is to focus on the minutiae of a human story rather than get caught up in wider political issues.

“The nouns will change, the places will change, the conflicts will change,” said lyricist Brock Walsh. “But there will always be conflict, and there will always be a need for people to respond, and to respond humanely.”

The New York Philharmonic Orchestra will perform Émigré on Thursday, Feb. 29, and Saturday, March 1.