‘Things have souls’: How a handwritten letter from 1879 became a very special bar mitzvah tallit

This tallit weaves multiple generations and cherished family artifacts into its fabric

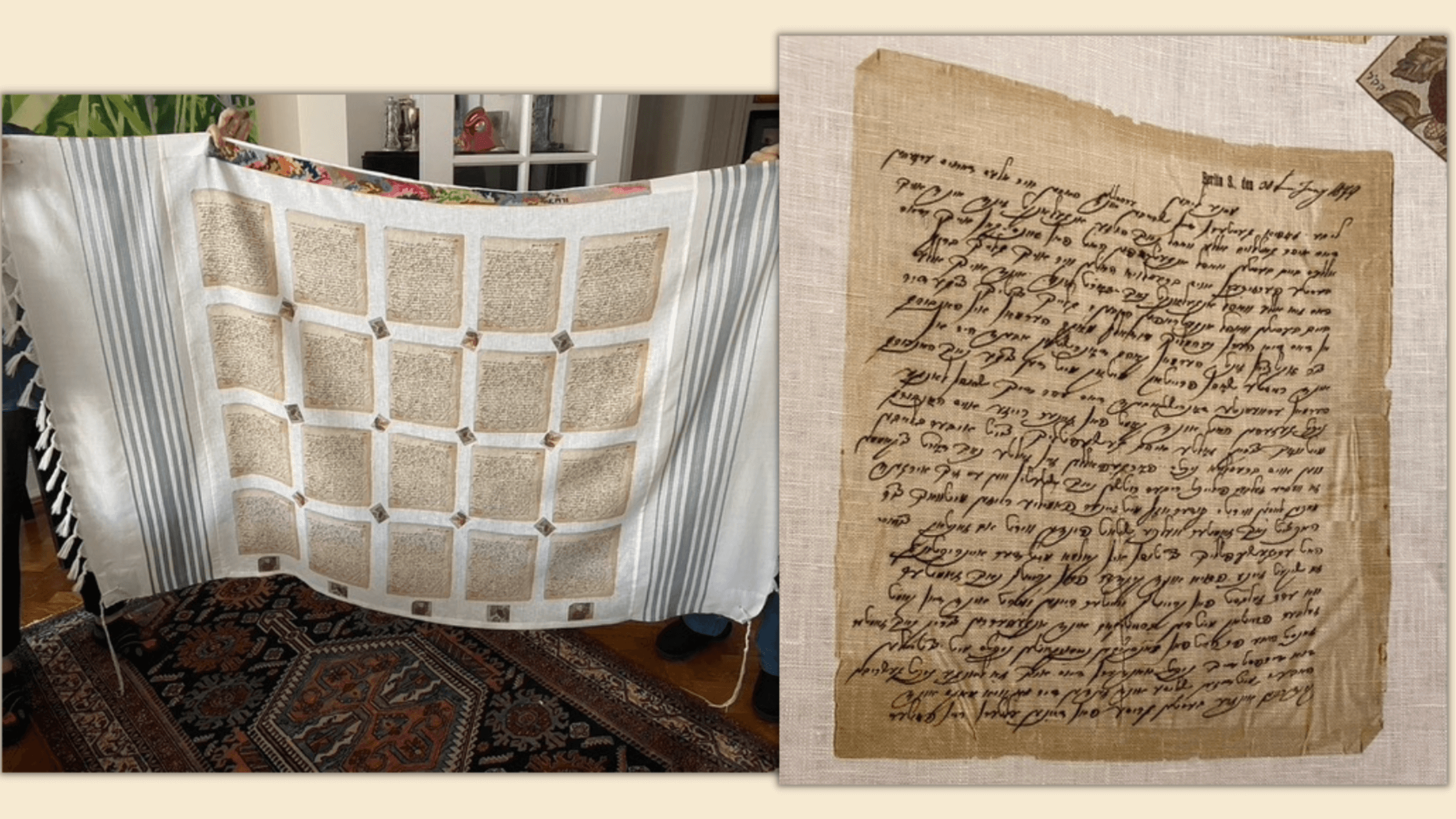

The tallit, and the original 1879 letter from Simon Freudenheim to his daughter Sophie. Courtesy of Tom Freudenheim

When Simon Emil Freudenheim becomes a bar mitzvah this Saturday, he will be wearing the most astonishing tallit I’ve ever encountered. It is made of a letter handwritten in an amalgam of Yiddish and German by his great-great-great-grandfather, and its backstory is a mosaic of history, art, tradition, technology and community.

The contents of the letter are rather mundane. It’s dated June 30, 1879, on stationery from a “Warehouse for all kinds of Woods and Veneers,” and details the comings and goings of various folks — Rudolf, Max and Hermann are in Hamburg for an auction, Hermann might “slide his way over to Stettin” before heading with his family to a wedding in Samter, etc.

“Otherwise I have no news to tell from today,” it concludes. “You shouldn’t wonder why I haven’t written for so long.”

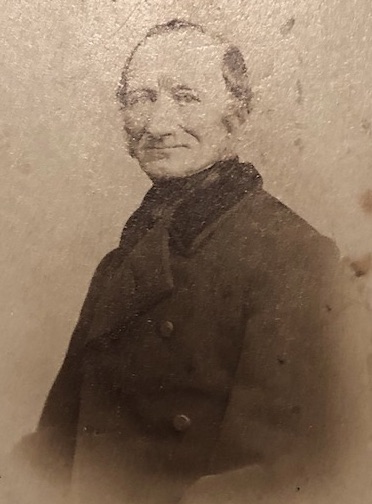

What’s special about the letter, of course, is its author: Simon Freudenheim, the ancestor the bar mitzvah boy was named after, who was writing to his daughter Sophie on stationery from his son Max’s business. It’s the only one in the elder Simon’s hand that has survived the 138 years since his death. Now it’s been immortalized, thanks to a man with both deep reverence for family history and remarkable artistic vision.

“I always say, ‘things have souls,'” said that man, Tom Freudenheim, granddad of the bar-mitzvah Simon, great-grandson of the letter-writing one. “It’s not about ‘Jewish’ and ‘art,’ but very much about how ‘things’ can have ‘souls’ and how — for better or worse — I live surrounded by those souls, and I want to pass some of that feeling on.”

A newsletter-worthy tallit

Tom, who was born in Stuttgart, Germany, in 1937, is an accomplished art historian who has run museums in Baltimore, London and Germany, and held high-ranking posts at the Smithsonian Institution and the National Endowment for the Arts. He is also a member of the Forward Association, our governing board, and perhaps the most devoted reader of this newsletter, who emails every Friday afternoon with feedback and tidbits from his travels.

Including last Friday, when there was no “Looking Forward.” So instead of commenting on my commentary, Tom sent pictures of the just-finished tallit, which seemed more than worthy of a newsletter of its own.

Simon is the youngest of Tom’s five grandchildren, so this is Tom’s fifth go at finding or creating a unique Jewish prayer shawl. He bought the first, from one of the myriad artists who have turned Jewish ritual objects into collectors’ items. The second Tom designed, incorporating the family Tartan of the bar mitzvah boy’s maternal grandfather, a famous Scottish rugby player. The next two were fashioned from tablecloths that were in Tom’s mother’s trousseau in 1932 Germany, and embroidered fabrics made by other ancestors.

Some of the carrying cases, including Simon’s, are crafted from needlepoints stitched by Tom’s mother-in-law. “Disclosure,” Tom wrote in an email. One of the grandkids “apparently doesn’t like her tallit and as far as I know hasn’t worn it, but that’s OK; it’s an artifact for her to keep.”

In addition to his great-great-great-grandfather’

Help from local artists

How do you make a tallit from a 138 -year-old handwritten letter and postage stamps? Meet Beth Schiffer, who for more than 30 years has worked with photographers and fine artists to create large-scale prints for exhibitions and out-of-the-box projects. In her downtown studio, Schiffer has a special ink-jet printer that can transfer scanned images to fabric. She once turned the campy self portraits of the artist Kenny Kenny — “one of the club kids from way back,” as she described him — into a bathrobe.

For Simon’s tallit, Schiffer worked with Tom (and Adobe Photoshop) to make a pattern out of the letter and stamps, then printed it on a 55-inch-wide white linen, charging $1,000. “Anybody comes to me with an unusual project, I’m really gung ho,” Schiffer told me. “Being Jewish, and working with somebody like Tom, made it a little bit more interesting and a little bit more fun.”

Next Tom turned to Flora Ferrara, a neighbor in his Upper East Side building who goes on weekly walks with his wife of 58 years, Leslie. Ferrara, who is British, once worked in the costume department of England’s National Theatre, sews her own clothes, and has made pillows and other small things for interior decorators. She is the type of person who periodically wanders around the Garment District because she just loves fabric, and who “always has to have a project on the go,” as she put it — lately, she has been embroidering tiny monogrammed tote bags as baby gifts for the friends of her adult children.

A statement of ‘who they are’

Simon’s is the fourth of Tom’s tallit projects Ferrara has pieced together. She won’t take payment, so Tom and Leslie make donations in her honor to her church, St. Bartholomew’s on Park Avenue.

“I have been to a couple of bar mitzvahs and I actually find them really moving,” Ferrara said. “You know, these are young people who are sort of making this statement about who they are. There’s nothing quite the same at that time of life in the Christian Episcopalian tradition, and I thought it was kind of wonderful that they’re being welcomed into adulthood in a very moving way.”

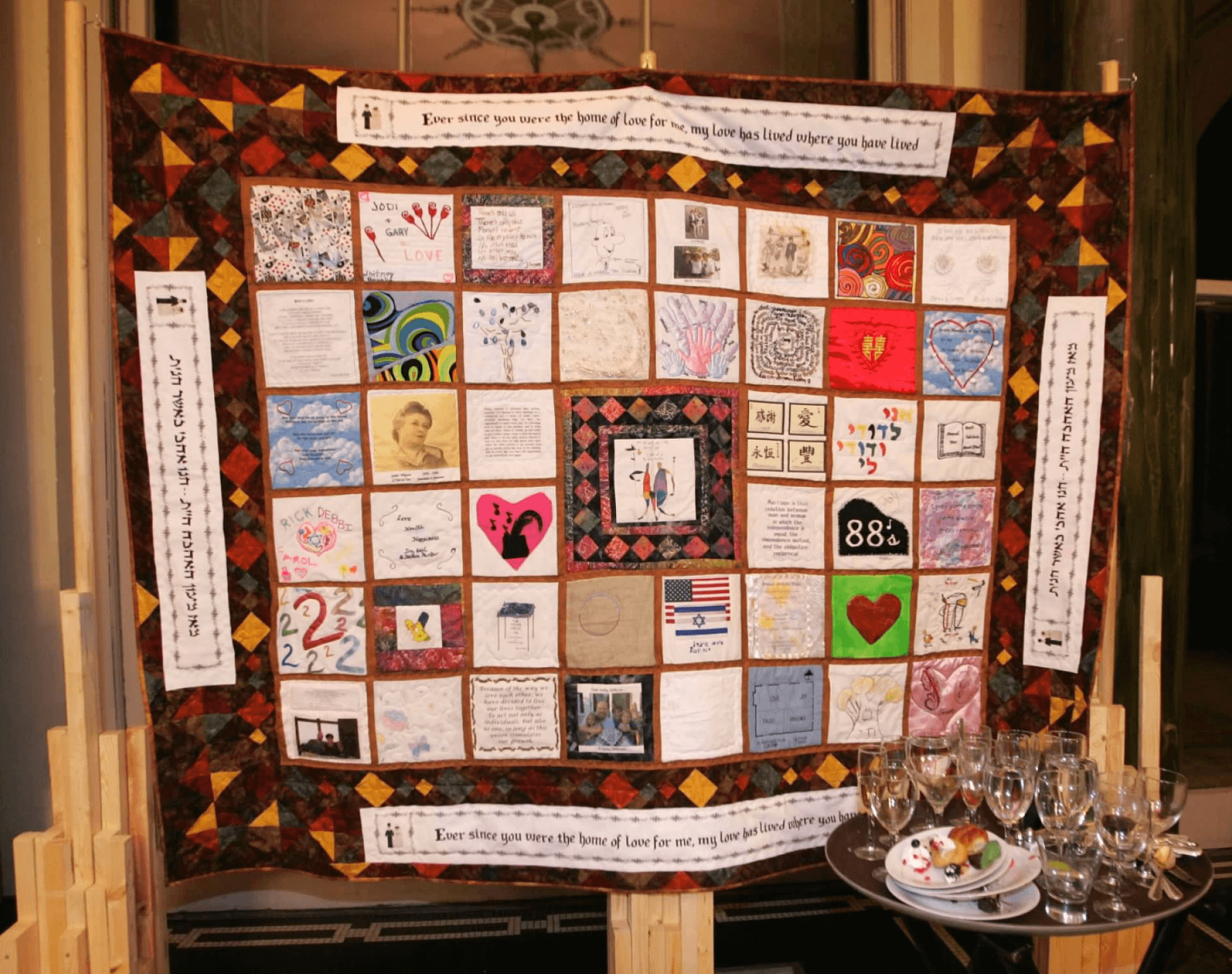

I was especially intrigued by Tom’s tallit projects because my own mother, like Ferrara, is an inveterate crafter who always has multiple projects “on the go.” I am currently storing six large tubs of hand-knit “baby sweaters for the great-grandchildren” she does not yet have. Mom cross-stitched a verse for my chuppah — a quilt that also incorporates photos printed on fabric and remnants of relatives’ wedding dresses and handkerchiefs — and needlepointed the tallit bags for my kids’ bnei mitzvah two years ago.

I have never owned a tallit and only wear one when called to the Torah, likely because I grew up in an Orthodox shul where prayer shawls were the sole purview of men. Ironically, Tom said his father bought him a basic tallit for his bar mitzvah, but he did not wear it at the ceremony, because tallit were not generally used in their Reform synagogue in Buffalo at the time.

‘I had to have it’

Decades later, on a family trip to Israel in 1979, Tom’s dad bought him a big, traditional tallit in Jerusalem. Soon after, his mom said she wanted to have a more distinctive one made for him, and on the High Holidays in 1982, Tom fell in love with a woven tallit worn by a man in the row in front of him in Worcester, Massachusetts. “I had to have it,” Tom recalled. “So I followed him out of shul and asked him where he got it.”

The tallit had been woven by the wife of the man’s college roommate, who lived in Rochester, New York. Welcome to our small Jewish world — the roommate was the son of an old friend of Tom’s father, a man named Irving Norry, who’d had a small business in Rochester. “In 1948, when our house was a depot for storing guns for Israel (that’s another story) and I sat in the car for night rides to NYC to make sure my father stayed awake,” Tom explained in an email, “we would first stop in Rochester and pick up the guns in Irving Norry’s warehouse and then drive further to the NYC docks.”

So, Sharon Norry, daughter-in-law of Irving, wove a tallit for Tom and, later, for each of Tom’s sons’ bnei mitzvah. All three are stored in custom-made velvet bags with Palestinian embroidery that Tom and Leslie bought in the Old City right after Israel captured it in the 1967 war.

‘Everything around me is meaningful’

‘I’m a ‘thing’ person,” Tom said. “I’m sitting here in my office right now and everything around me is meaningful.” Some of those things are original artworks, some are heirlooms connected to relatives lost in the Holocaust. There’s a photograph of his father on his 25th birthday. And there are also bobbleheads of both the Pope and Sholom Aleichem, and a doll of The Dude from “The Big Lebowski.” But they’re not mundane to Tom.

“When we moved from our big house in Washington, I had no trouble at all distinguishing the things I had to keep and the things that didn’t matter to me,” Tom said. “The things that have souls and the things that don’t have souls.”

Mazel Tov, young Simon, on your bar mitzvah. Know that it took a village to make your tallit, and always remember that everything has a story. May you always be surrounded by things that have souls.