Bernie Sanders Stint at ‘Stalinist’ Kibbutz Draws Red-Baiting From Right

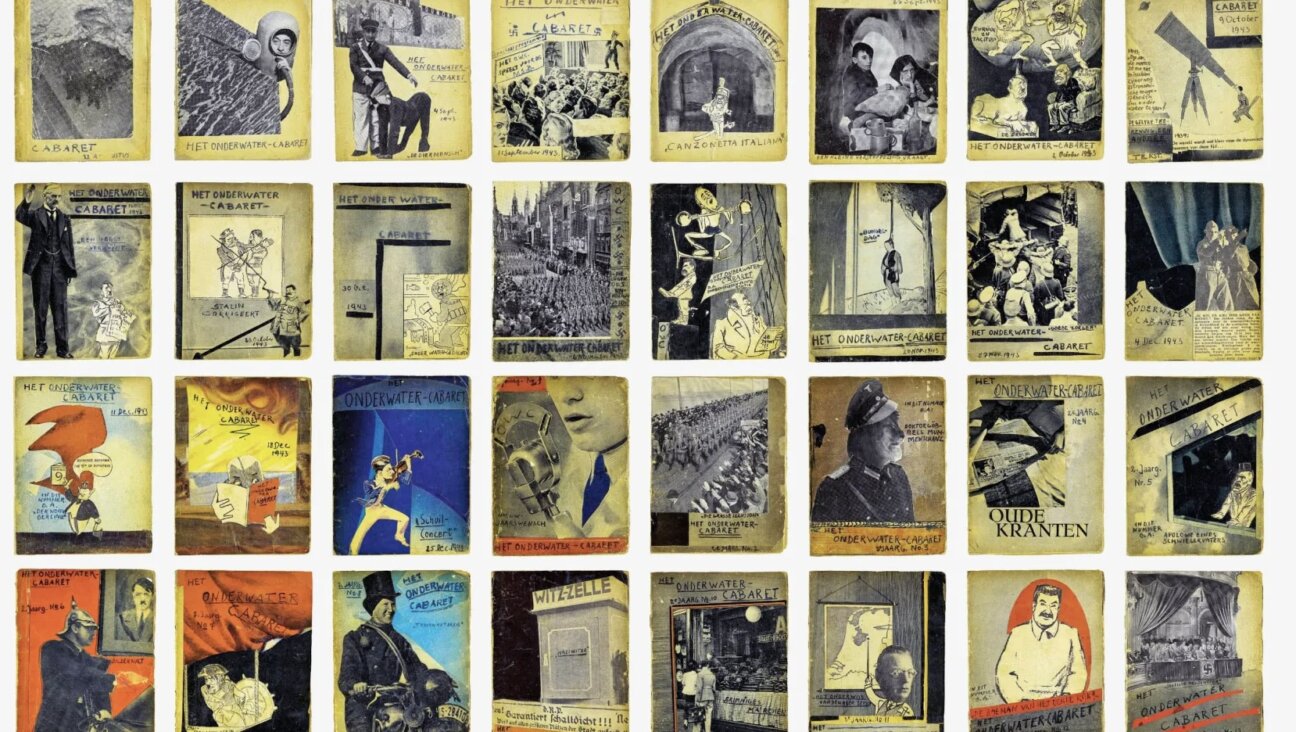

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

It didn’t take long after news broke that Bernie Sanders had volunteered decades ago on a hard-left kibbutz in Israel for right-wing critics to start lobbing ever-scarier adjectives at him.

The Democratic presidential candidate’s stint at Kibbutz Sha’ar Ha’Amakim in northern Israel proves to conservatives that he isn’t just a “socialist” but a hard-core Marxist or even a “Stalinist,” far outside the American mainstream.

“Bernie Sanders’s 1963 stay at a Stalinist kibbutz,” was the title of Thomas Lifson’s piece on the site American Thinker, posted soon after the kibbutz was identified after months of mystery. Over at Frontpage Magazine, Daniel Greenfield’s article ran under the headline: “Bernie Sanders Spent Months at Marxist-Stalinist Kibbutz.”

The descriptions seem damning, especially from the perspective of more than 50 years since Stalin’s death and the world’s absorption of the reality of his murderous, dictatorial and anti-Semitic regime. Yet at the time, as the two right-wing websites point out, Hashomer Hatzair, the kibbutz movement that Sha’ar Ha’Amakim belonged to, had quite a different perspective.

On the day of Stalin’s death, March 5, 1953, the front page of Al Hamishmar, the movement’s newspaper, carried a photo of the late Soviet leader under a full-width headline: “The Progressive World Mourns the Death of Stalin.” Greenfield at Frontpage concludes: “Bernie Sanders wasn’t there because he liked Israel. Hashomer Hatzair did not like Israel. It ultimately wanted to destroy it.”

The movement’s admiration years earlier for Stalin notwithstanding, that is a perspective it would be hard to find any historians to support, given Hashomer Hatzair’s central place within the Zionist movement from its earliest days. Hashomer Hatzair’s contributions to Zionism have included the service of many of its leaders as Israeli government ministers, and the role of many of its members in the pre-state Zionist military force, the Haganah, its shock troop militia, the Palmach, and later, the Israeli military. The heroism of Haviva Reich, a Hashomer Hatzair member who died trying to rescue Jews in Europe during the Holocaust, is taught even today to Israeli school children alongside the parallel effort of Hannah Senesh, whom the Nazis also caught and killed.

Nevertheless, in Lifson’s view, Sanders’ “sojourn in an Israeli communist kibbutz is fully consistent with Sanders’s honeymoon visit to the Soviet Union… his visit to Nicaragua’s Sandinista revolutionary leader Daniel Ortega as the first U.S. elected official … and his 1980s visit to Cuba where he met with the mayor of Havana….So far as I know, Bernie Sanders has never repudiated his Stalinist inclinations.”

According to Greenfield, “He was there because he was far left. Perhaps even further left than he has admitted.”

Sanders’ time on the kibbutz, where he lived for a few months with his ex-wife, Deborah Messing (born Deborah Shiling), is referenced in virtually every profile of the candidate. But the Sanders campaign has been tight-lipped about the name of the kibbutz, leaving journalists in Israel and the U.S. searching fruitlessly for months. It was only on February 4 that Yossi Melman, a longtime Israeli national security journalist, unearthed a 1990 interview he did with the candidate in the Israeli Haaretz newspaper, in which he revealed that the kibbutz in question was Shaar HaAmakim.

A member walks by a grain silo at Kibbutz Sha’ar Ha’amakim in northern Israel. Image by Tomer Dikerman

By 1963, when Sanders did his volunteer work, Hashomer Hatzair’s admiration for Stalin had greatly faded, though not yet vanished. At the time, no one thought it unusual. Nevertheless, the movement’s historic sympathy for the ruthless Soviet leader is viewed as astonishing nowadays.

From Israel’s founding in 1948 to at least a couple of decades afterward, Israel’s dominant political and social culture was socialist. Most of the intense ideological debate among its political intelligentsia focused on what flavor of socialism had the correct line. Even under Stalin, the Soviet Union, after its massive national sacrifice of more than 20 million lives in the battle to defeat Hitler, was viewed by segments of the Zionist-left as a model society worthy of adoption, at least in part, by the nascent Jewish state.

Many were also grateful for Stalin’s crucial decision to provide arms to Israel, through Czechoslovakia, at its birth, in 1948, when armies from five Arab countries attacked it and sought to choke the new state in its cradle. During this same period, in contrast, the democracies of the West were enforcing a ban on arms sales to all parties involved in the conflict, effectively hamstringing Israel’s efforts to obtain weapons against its better armed adversaries.

Still, the moderate left and the larger kibbutz movements took issue with Stalin’s dictatorship and his hostility to Zionism early on, leading to heated debates and painful breakups within kibbutzim. But Hashomer Hatzair was late to reach this recognition. The movement began to turn its back on the “Sun of the Nations” only after the 20th Congress of the Communist Party in 1956, when Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev gave a secret speech — soon disclosed worldwide — denouncing the recently deceased Stalin’s atrocities.

Image by Getty Images

By the time Sanders arrived at Sha’ar Ha’Amakim, in 1963, the kibbutz had cooled greatly on Stalin but was still a socialist heaven, practicing communal sharing in almost all aspects of life. But it is fair to assume that Stalin’s photos no longer adorned the communal dining room. The Internationale, a renowned workers’ anthem, was still sung at kibbutzim and youth movements many decades later.

Hashomer Hatzair was a staunchly Zionist movement back then and it remains so now. The group now exists mainly as a youth movement. It asserts the right of the Jewish people to a homeland in Israel, and its members have played key roles in Israel’s government and military.

Still, Sanders might have a hard time explaining all this to Americans – conservatives and liberals alike – whose views on Stalin, Marxism, and the Soviet Union were shaped through the prism of the Cold War, not that of the international socialist movement.

Moreover, he may also have to deal with critics from the left. Some on that end of the spectrum are already looking deeper into Kibbutz Sha’ar Ha’Amakim and the land it sits on. A commenter on the Forward website wrote: “keep in mind, Mr. Sanders was living and working on a ‘settlement’, despite the fact that it was a most socialist society you could ever dream of.”

Sha’ar Ha’Amakim, according to the Kibbutz’s official history, was established on land purchased by the Zionist movement from absentee Arab owners in 1925. Zionist historians point to documentation that the 60 or so tenant farmer families then actually working the land were compensated to evacuate it. But as with much historiography when it comes to land tenure issues in what was then Palestine under the British Mandate, facts and contexts are hotly disputed. When the kibbutz sought to evict the tenant famers and take control of the land in 1935, the local Arabs resisted.

For Sanders, it seems, finding the kibbutz he lived in 50 years ago, can bring nothing but trouble.

Contact Nathan Guttman on Twitter @nathanguttman