3 Jewish fathers and their pro athlete sons talk sports and Judaism

‘He was there, showing up,’ former NFL player Ali Marpet said of his father

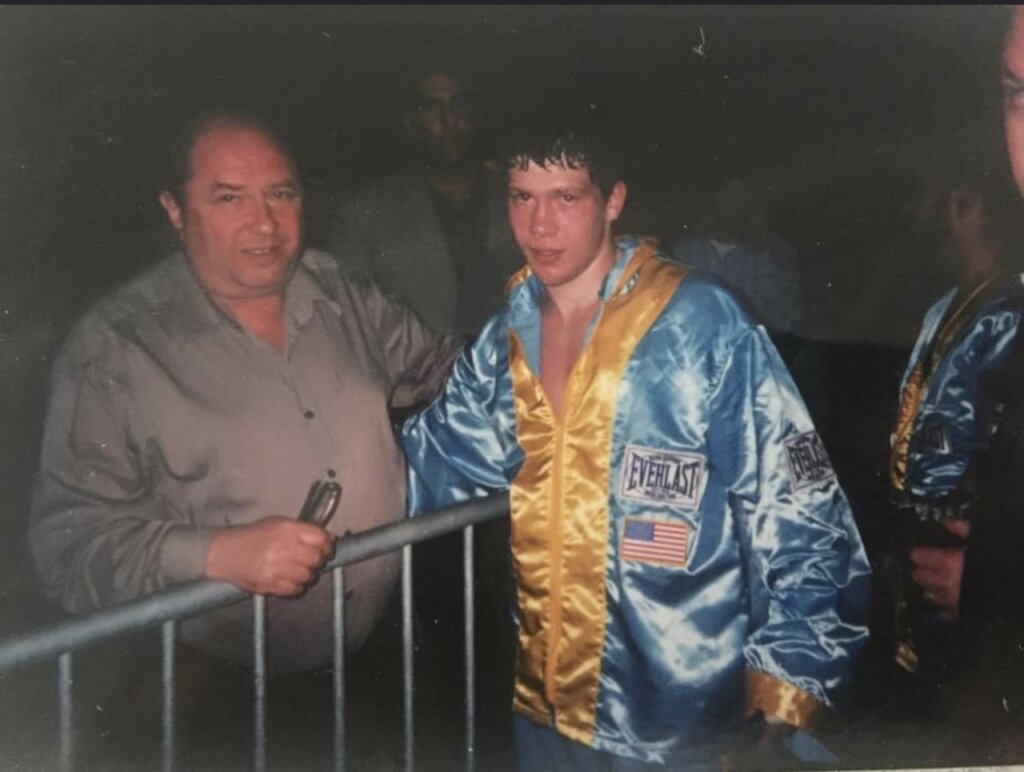

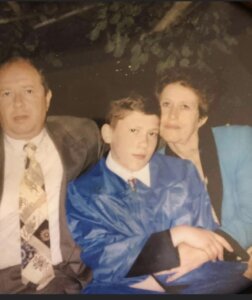

Clockwise from top, Jacob and Elliot Steinmetz, Bill and Ali Marpet and Aleksandr Lekhtman and Dmitriy Salita Image by Benyamin Cohen

Sports bonds many fathers and sons — whether it’s shooting hoops in the driveway or tossing a football in the backyard. Consider Kevin Costner’s character in “Field of Dreams.” He plows his Iowa cornfield into a baseball diamond just to play catch again with his long-deceased dad. And love for the hometown team is often passed down, somewhat Jewishly, l’dor v’dor.

The Talmud’s tractate of Kiddushin states that a father’s obligations include teaching his child Torah and a profession. Instructing one’s progeny on proper positioning to field ground balls may not only save their teeth but, in a few rare cases, lay the foundation for professional sports careers.

Supportive parents help make an elite athlete, said Avidan Milevsky, a U.S.-raised rabbi and psychologist who has researched family dynamics and teaches at Israel’s Ariel University. “No cheer of a fan is going to match the cheer of a mother or father.”

For Father’s Day, the Forward asked three Jewish pairs of dads and their professional athlete sons to talk about their relationship and sports.

Jacob Steinmetz, Arizona Diamondbacks’ Rookie League, and Elliot Steinmetz, coach of the Yeshiva University men’s basketball team

On Tuesday, Jacob Steinmetz, 18, made his first appearance this season, pitching a scoreless inning, striking out one batter and inducing a double play. It might help him forget his professional debut last season, which consisted of a nightmarish inning: four walks, a hit and a wild pitch. That game came soon after Jacob, as a high school senior at New York’s Hebrew Academy of Five Towns and Rockaway, signed with Arizona as its third-round selection in the Major League Baseball draft.

Elliot Steinmetz, 41, the head coach who led Yeshiva University on a 50-game winning streak and to two NCAA Division III postseason tournaments, has been along for the ride — and the walk.

As Orthodox Jews, the Steinmetzes book hotel rooms within walking distance of the field where Jacob’s teams play weekend games because of prohibitions against driving on Shabbat. That one-on-one time — the rest of the clan remained at their Long Island home — has included countless hourlong walks to and from the baseball fields, and encounters with deer, foxes and other wildlife.

“We used to have pretty morbid conversations about what would happen if an animal came out of nowhere: who’s going to run, who’s going to fight, who’s calling home afterward,” Elliot said. “What sticks out is the joking and talking.”

Together they figured out how to enter the hotels and their rooms without triggering sensors or using magnetic keys — which are forbidden on Shabbat — and where to procure kosher snacks.

Elliot, who is also a lawyer, drew on both his coaching and Jewish parenting skills as the two drove to Jacob’s games. “He gave me tidbits of advice,” Jacob said. “What I should say to coaches and how I should act around them, putting the team first, not being all about yourself.”

“What he said about the religious aspects and Shabbos taught me commitment and dedication from a young age, staying true to our religion,” Jacob continued. “I’m staying with it and walking to games even now.”

Said Elliot: “It’s amazing to watch your kid chase what he loves and succeed at it. I’ve probably learned as much throughout this process as he has.”

Ali Marpet, former Tampa Bay Buccaneer, and Bill Marpet

In March, Ali Marpet, 29, retired from a remarkable career in professional football. He started all 101 regular-season games and six playoff games in the seven seasons he played as an offensive lineman with the Buccaneers. With him on the field, the team won the Super Bowl in 2021. And this past season he earned his first Pro Bowl selection as a top player at his position (left guard).

Bill Marpet, 71, went to 95 of those games, flying around the country. The pandemic shut him out of a few, as did Fashion Week in New York — Bill’s Brooklyn-based company films events in the Garment District.

“The best ability is availability, and he was there, showing up,” Ali said.

During Ali’s professional career, Bill showed up in a different way than he did when his son was young, and he coached his baseball and basketball teams, and when Ali played football in high school and college.

“He had his own process for focusing. I totally respected that,” Bill explained of the Tampa Bay years. “I don’t think that I ever got in touch with him before a game. We socialized a lot more after football season than during. I tried to be hands-off.”

An exception was Hanukkah, when they lit candles together in Tampa. Bill made both men chuckle when he recalled that he didn’t bring presents. “Yeah, no Hanukkah gelt,” Ali said.

Ali remembered more about his father that Hanukkah night: “What stands out to me was the same boyish enthusiasm out of him lighting the candles and celebrating with his family.”

“I like to celebrate,” Bill agreed. “After we light the Shabbos candles, we sing ‘Shabbat Shalom’ and get all pumped up. We’re not super-religious. It’s more about being with each other.”

They celebrated again in Tampa in February 2021, following the Super Bowl win. Bill had watched the game with another dad, the father of safety Antoine Winfield Jr. As confetti swirled in the air, the teary fathers rushed the field.

“I saw Ali, and he just gave me the biggest hug and told me how much I meant to him. We had a moment when it was the two of us. Ali’s holding me, we had our arms around each other and I told him: ‘You’re going to be a Super Bowl champion forever.’”

Ali’s next career move is an unusual one for a former pro athlete. He plans to pursue a degree in mental health counseling or marriage and family therapy. He was inspired, he said, by locker room talk about relationships, and the pandemic, in which many people began sharing their struggles more openly.

He also said he thinks of the parent he wants to be one day, and how he draws inspiration from his father.

“The biggest role I see as a parent is being the type of person you’d want your kid to be, and surrounding them with a ton of love, and those two things were done for me,” he said. “That’s my experience with him, and that’s what I want to instill in my kids.”

Dmitriy Salita, retired professional boxer and boxing promoter, and Aleksandr Lekhtman

As a boy in Ukraine, Dmitriy Salita had first wanted to play soccer. But Odesa’s clubs didn’t take kids under 9. His father, Aleksandr Lekhtman, saw a newspaper ad about karate classes for younger children and enrolled Dmitriy. He excelled at the sport. And when the family immigrated to the United States in 1991, their Brooklyn neighborhood’s karate club offered kickboxing. Dmitriy excelled at that, too.

He was a skinny kid, and was sometimes ridiculed by other boys when he began to enter tournaments. Aleksandr, 74, recalled one in particular: “Everybody was laughing at [Dmitriy] because they thought it was going to be an easy victory, but the opposite happened.”

Dmitriy, now 40, said he began to believe in himself thanks to Aleksandr’s support. “When we came here, my family didn’t have any money, but they still found money for me to attend the kickboxing club. I’m definitely grateful for that,” he said.

Dmitriy began boxing when he was 13. He saw more of a future in the sport, and a city-subsidized club not far from his home offered free training. “Being an immigrant and going through my challenges, I saw boxing as a way out of my ghetto,” he said.

Dmitriy went 59-5 as an amateur in three weight divisions, earning a bronze medal at the U.S. Junior Olympics, becoming an Under-19 national champion and winning a New York Golden Gloves title. He went 35-2-1 as a professional and held regional titles from four American boxing associations.

Some have speculated that antisemitism experienced as a child in Odesa and Brooklyn helped push Dmitriy into boxing. But that wasn’t why he got picked on, he said, owing it to other kids’ singling him out for his accent.

His parents, Aleksandr and Lyudmila Salita, always attended his matches, Dmitriy said. But then Lyudmila was diagnosed with breast cancer. She died in 1999 and Dmitriy took her last name.

Around that time, Aleksandr drove Dmitriy and other boxers to a Silver Gloves tournament 200 miles away. The temperature dropped, and the car’s heater stopped working. Dmitriy looks back on that frigid trip fondly. “I was very happy that we had a chance to spend time together. Now, as an adult, I’m grateful for those experiences with my dad.”

Dmitriy said he also remembers that in Odesa, his father managed to keep Judaism alive for the family, though like most Soviet-era Jews, they faced obstacles to Jewish learning and practice.

“Somehow, my father found a way to buy matzo” for Passover, Dmitriy recalled. “We didn’t know most other things, but to his best ability he’d tell me the story of the exodus from Egypt and what matzo meant: that we were slaves and had to get out of there fast.”

Dmitriy’s relationship to Judaism strengthened in adulthood. He began to observe Shabbat, and would schedule his Saturday night bouts for when he could get to arenas after nightfall. He sends his two daughters to a Jewish school near their Detroit-area home.

Today, he said, “I am Orthodox, fully observant, much advanced in my knowledge since my fighting days.”