Nazi monuments removed amid ongoing Forward investigation

Virginia, Bosnia, Belgium and Australia have renamed streets or taken down statues honoring collaborators

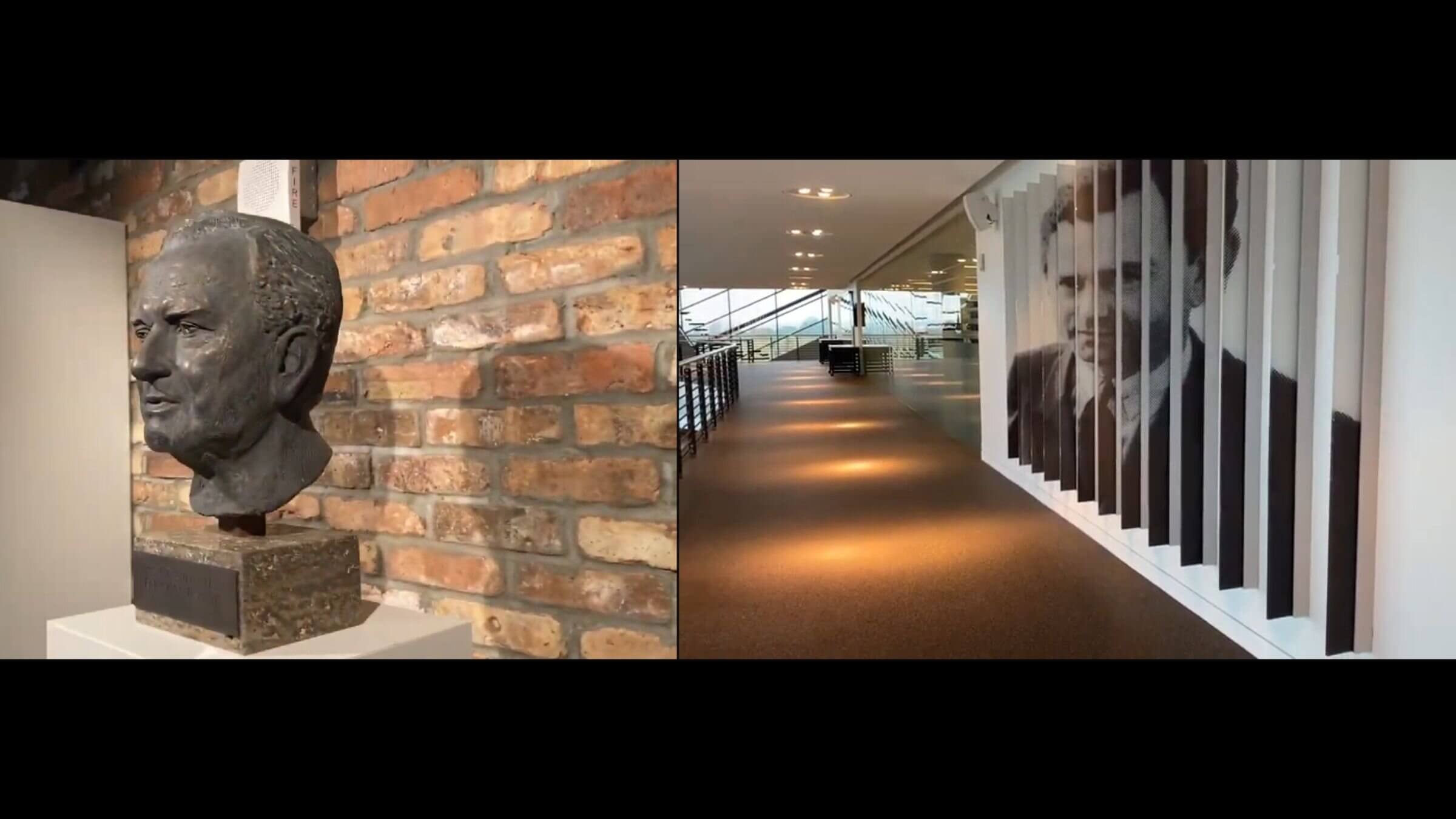

Ferry Porsche bust, Porsche Experience Center Atlanta, left. Porsche photograph polyptych, Porsche Experience Center Atlanta, right. Image by Forward collage, from YouTube

This article is part of an ongoing investigative project the Forward first published in January 2021 documenting hundreds of monuments around the world to people involved in the Holocaust. If you know of streets, statues or other emblems honoring Nazi collaborators not included in our country-by-country lists, please email [email protected], subject line: Nazi monument project.

Streets in Virginia and Bosnia that honored Nazi collaborators have been renamed. An art gallery in Australia no longer bears the name of a Lithuanian who worked as an intelligence officer for the Third Reich.

And, nearly a year after pledging to remove a monument celebrating Latvian soldiers in the military wing of the Nazi Party, a Belgian town finally did so this summer.

These are among the changes that have occurred amid the Forward’s ongoing, award-winning investigation documenting some 1,500 instances in which cities and towns around the world continue to uplift people who were complicit in the Holocaust.

A whitewashing of history

Many of these monuments reflect a whitewashing of history engineered by far-right forces, others unwitting ignorance. A small but growing resistance from individuals, local media and watchdog organizations has begun to call them out.

The Forward first published an article and lists of 320 such monuments across 16 countries in January 2021. A year later, in January 2022, we reported on an additional 1,135 streets and statues, in a total of 25 countries — including in eight U.S. states and five Western European nations.

And while several places have recently moved to erase these paeans to people with dark pasts, we have continued to learn of more such monuments, including a bust of Ferry Porsche that sits in the North American headquarters of his family’s eponymous car company in Atlanta.

Ferry Porsche, who died in 1998, was one of two children of Ferdinand Porsche, the Austrian automotive engineer who was responsible for the car company that bears his name as well as the Volkswagen Beetle and the Mercedes-Benz SS/SSK — and who manufactured weapons for the Third Reich. Like his father, Ferry Porsche was a member of the Nazi Party and an SS officer involved with slave labor.

Ferry, who ran the auto company after World War II while his father was imprisoned in France for war crimes, is also honored with a street and a convention center in Austria and a kindergarten in Germany.

Atlanta’s Porsche Experience Center

In Atlanta, the bust of Ferry — and a photo installation about his life — sits in the Heritage Gallery of the Porsche Experience Center, which contains a restaurant and racetrack, and bills itself as a venue for weddings and corporate events.

When Porsche opened its headquarters there a decade ago, the company attempted to name the street it is on after its founder, Ferdinand Porsche, but the city of Atlanta nixed that idea because of his Nazi past and ties to Hitler.

Other monuments we have learned about in recent months are:

- In Wiener Neustadt, Austria: a bust, street and university all honoring Ferdinand Porsche. (Other Austrian things bearing his name include a museum in Mattsee and streets in Felixdorf, Knittelfeld, Leibnitz and Wals-Siezenheim.

- In Germany: “Ferdinand Porsche” streets in Erkelenz, Freudenstadt and Tarp, plus a street in Henstedt-Ulzburg named for Nazi Party member Kurt Körber, who was technical director for a company that had 3,000 slaves. And a second bust honoring Klaus Riedel, who helped develop the deadly V-2 rocket used by Nazi to shell Britain and other Allies, in the town of Bernstadt auf dem Eigen, where Riedel was raised.

- In Ukraine: Dnipro recently named a major thoroughfare for Nazi collaborator Stepan Bandera, whose troops massacred Jews in the Holocaust; there is also a Bandera monument in Tatariv.

A change in Virginia

Meanwhile, in Herndon, Virginia, the street where Volkswagen’s North American headquarters is located has been renamed from Ferdinand Porsche Drive to Woodland Pointe Avenue. Signs with the new name have been up since at least June, according to Google maps; records regarding the name change were filed with Fairfax County in 2021.

The Bosnian city of Mostar also voted in July to rename six streets that had glorified leaders of Croatia’s fascist Ustasha regime, which had collaborated with Hitler and exterminated hundreds of thousands of Jews, Serbs and Roma. The streets included five highlighted by the Forward’s investigation.

Two of the streets now bear the names of national poets, and another honors a Mostar priest celebrated for his work with war wounded and local hospitals.

Israel’s foreign ministry praised Mostar’s move as “historic,” saying on Twitter: “This change will undoubtedly further strengthen the relations between our peoples.” A European Union official commended Mostar for being inclusive and called on other towns to follow suit.

An Australian city takes action

Around the same time, a city-owned art gallery in Wollongong, Australia, removed the name of Bob Sredersas, a European who had arrived in the city in 1950 and helped grow its steelworks while amassing a fine art collection.

A former Wollongong councilman, Michael Samaras, began looking into Sredersas’ past in 2018, the 40th anniversary of the steel man’s gift to the art gallery. He was helped by Efraim Zuroff of the Simon Wiesenthal Center.

An exhibition mounted for the 40th anniversary of the gift said that Sredersas had included an essay saying that “Bob’s story goes quiet during the second world war” and that the benefactor had been reticent “to talk about himself and his past.” Now, decades after Sredersas’ 1982 death, Samaras found archival evidence in Lithuania suggesting that he served during World War II in the intelligence arm of Nazi Germany, which contributed to the murder of 212,000 Lithuanian Jews.

Wollongong had initially balked at Samaras’ revelations, but after a March article in The Guardian, the city worked with the Sydney Jewish Museum to investigate the matter. This June, Wollongong announced the allegations were confirmed and the gallery was renamed.

Zuroff, an American-Israeli historian who has been involved in hunting Nazis for decades, said Wollongong was unusual because “unlike most of the statues and monuments erected to honor Nazis,” the people who had named the gallery “had no idea that the donor had served in the Nazi security service in Lithuania.” And because an individual “took the trouble to investigate,” he added, “so hats off to Michael Samaras, who saved dignity of the victims.”

Indeed, it is a rare example of citizens, local government, experts and journalists decisively and deliberately exposing such a whitewashing. A crucial part of the process was Wollongong’s decision to work with historians to corroborate Samaras’ findings, which added an extra layer of credibility.

“Wollongong is basically a Labor city with a long history of anti-fascism so I always believed that the council’s initial reaction could not be sustained,” Samaras said via email. He said he was impressed by the city’s commitment to use this incident to educate the public, with a joint presentation between Wollongong and the Sydney Jewish Museum planned for next year.

“Overall, I think it has been very worthwhile,” he added. This summer also saw the long-promised removal of the “Beehive to Freedom,” a monument honoring Latvian soldiers in the Waffen-SS, from the town square in Zedelgem, Belgium.

After the Forward’s initial exposé of this monument, the town had pledged in August 2021 to rename the square and remove the plaque honoring the soldiers, with its mayor saying any offense was unintentional. The Latvian foreign ministry and ambassador to Belgium waged a campaign pressuring Belgium to keep it, but Zedelgem followed through this summer in removing the “Beehive.”

The Forward will continue to report on removals of Nazi-related monuments, and to update our country-by-country list of such statues and streets. If you know of examples not included in our lists, or changes being made, please email [email protected], subject line: Nazi monuments.