Special ReportBehind the TV ads against antisemitism: a fortune assembled under apartheid

Natie Kirsh made a fortune in South Africa and the U.S. What can his life tell us about the Shine A Light campaign against antisemitism?

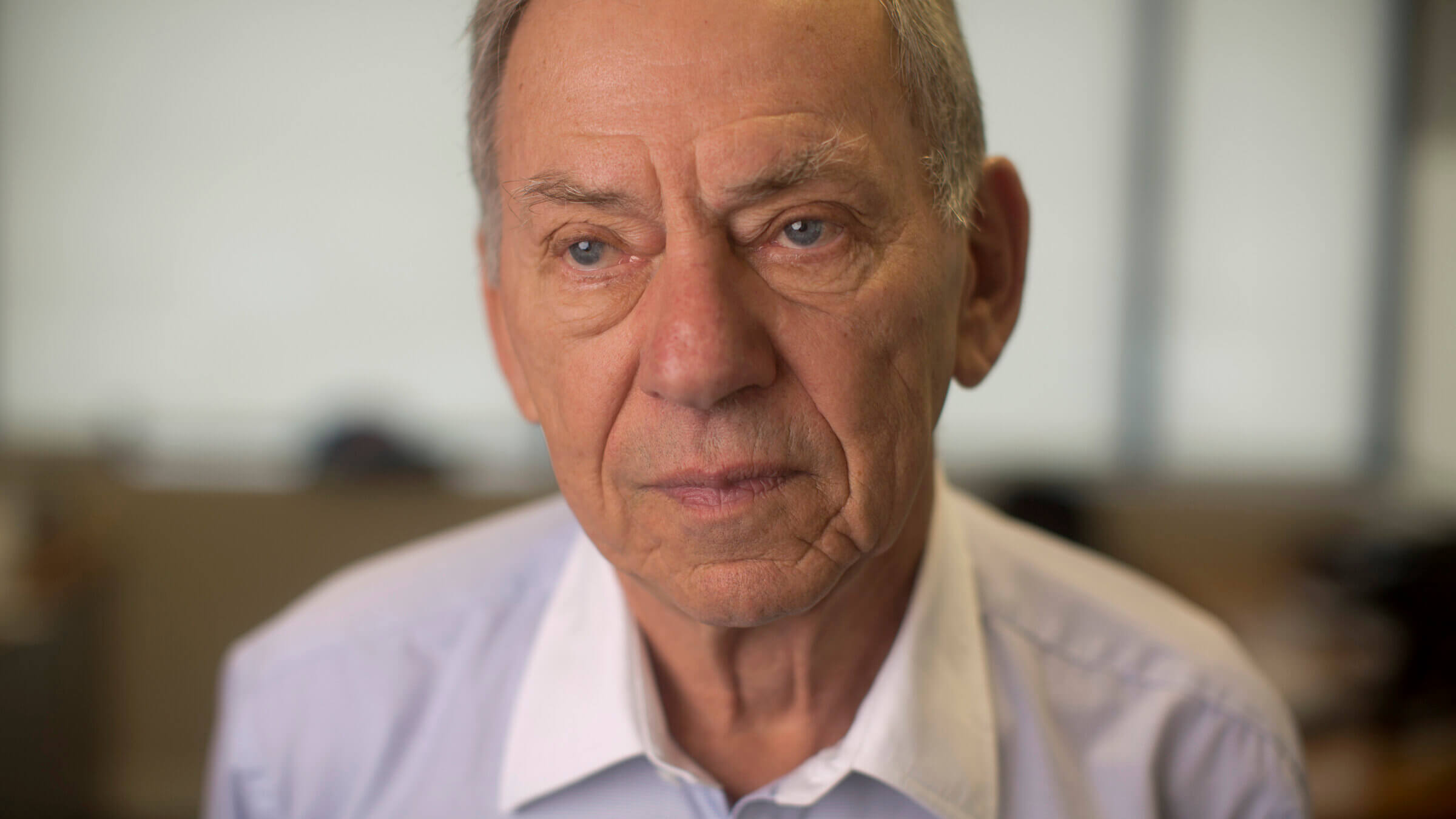

The family of Natie Kirsh, a Jewish billionaire from South Africa, spearheaded the creation of Shine A Light. The campaign to raise awareness about antisemitism in the United States has assembled an elusive coalition of organizations at a time when the Jewish community is divided over how to define and fight bigotry, but divisions in its ranks remain. Photo by Getty Images

The narrator of a 30-second commercial during Saturday Night Live had a jarring message for viewers expecting another fast-food jingle or car insurance pitch.

“There is one form of hatred on the rise in the U.S. often passed off as legitimate discourse or just ignored,” she intoned as animated words flash onto a bright background. “Shine a light on antisemitism. Together, we can dispel the darkness.”

The public service announcement, which first aired in December, is part of Shine A Light, a new high-profile campaign of advertising, public events and corporate partnerships responding to rising antisemitism in the United States. Mayors from Los Angeles to Miami Beach have attended Shine A Light events, and Fortune 500 companies have worked with the organization on employee trainings. The campaign’s high production value has been recognized with a prestigious award for social media content.

Shine A Light is one of more than two dozen new groups that have sprung up to fight antisemitism in the last decade, and is backed by eight major foundations including Schusterman Family Philanthropies, the Paul E. Singer Foundation and UJA-Federation of New York. It is the brainchild of the Kirsh family, led by 92-year-old patriarch Natie, a billionaire who built and lost a fortune in apartheid South Africa and has maintained strong ties to Israel for decades — experiences that may provide clues to the campaign’s approach.

Founded amid the fallout of the May 2021 escalation in violence across Israel and the Gaza Strip, Shine A Light defines some popular forms of Israel criticism as antisemitism. Several larger progressive Jewish groups are notably absent from the coalition, underscoring the challenge of pitching a big tent at a time when the Jewish community has been divided over how to defend itself.

Nonetheless, Shine A Light has managed to assemble an elusive coalition, winning the support of every major Jewish denomination and sometime rivals like the Anti-Defamation League and American Jewish Committee.

“There are many dogs fighting antisemitism and they don’t collaborate as much as they can,” said Andres Spokoiny, director of the Jewish Funders Network. “If the funders can use their influence to help them collaborate — that’s great.”

Because the project is structured as a private corporation, rather than a nonprofit, its finances are private beyond what the project has disclosed — a $4 million annual budget — and it’s unclear how much each foundation contributed to the campaign.

But the initiative was spearheaded by the family of Natie Kirsh, whose estimated net worth is $7.6 billion, according to Bloomberg, making him the world’s 300th richest person. Kirsh has quietly been an important donor to Jewish causes for decades, particularly those focused on security, but has said little publicly about his philanthropy or his politics.

Shine A Light did not acknowledge multiple requests to interview him about the organization or his life. Instead, Carly Maisel, who manages the Kirsh family’s philanthropy and has served as a spokesperson for the project, spoke with the Forward in a brief telephone call. Maisel and representatives for Shine A Light stopped responding after the Forward sent detailed questions about the project’s finances and Kirsh’s business activities in apartheid South Africa.

Maisel previously worked for the Israeli embassy in London and has described herself as “always on loan” to Ron Prosor, Israel’s former ambassador to the United Kingdom. She said her first engagement with Israel stemmed from antisemitism she experienced during college in the U.K.

Shine A Light grew out of a member of the Kirsh family’s concern that antisemitism stemming from the Israeli-Palestinian conflict had reached a fever pitch in the United States following the 2021 violence, a feeling echoed by numerous Jewish groups the family already supported.

“Something made the Jewish community feel there was a particular sea change,” Maisel said.

The connection between anti-Zionism and antisemitism “is front and center a part of Shine A Light,” Maisel said on a Jewish Funders Network podcast in January. “If that doesn’t work for you, this isn’t the campaign for you.”

Explaining antisemitism — and Israel

Before Shine A Light, the Kirshes helped build the shared security infrastructure for Jewish institutions in New York over the past four years, following an uptick in antisemitic violence. It was a centerpiece of that effort, the Community Security Initiative, that led law enforcement to two suspects accused of plotting to attack synagogues last fall.

With Shine A Light, though, the family entered a philanthropic arena crowded by organizations that can be hard to herd, each with its own politics and approach to advocacy. The ADL, AJC and the Combat Antisemitism Movement, for example, each run separate programs for mayors.

All three of those organizations were among nearly 100 groups that signed onto Shine A Light including liberal religious organizations like the Union for Reform Judaism and Reconstructing Judaism, which have been missing from similar coalitions backed by wealthy Republican donors. The project takes pains to place its members on equal footing by listing them in random order on its slick website.

One throughline in Shine A Light’s work is the idea that people inadvertently perpetuate antisemitism because they don’t understand what it is. “Jews don’t necessarily fit into one box of the way people are used to thinking about discrimination,” Maisel said in the phone interview. “You actually have to take people on a journey.”

Much of that journey presents Jews as being at odds with the political left. This is an increasingly popular perspective among Israel supporters, despite longstanding American Jewish support for the Democratic party and left-wing causes. Shine A Light specifically highlights complaints that Black Lives Matter and other movements to address institutional racism have ignored anti-Jewish bias.

Kenneth Marcus, director of the Brandeis Center for Human Rights Under Law, which works closely with Shine A Light, said that in the progressive movement, “Jews are often seen as being a powerful white group that does not need the kind of support that they’re offering to other minority groups.”

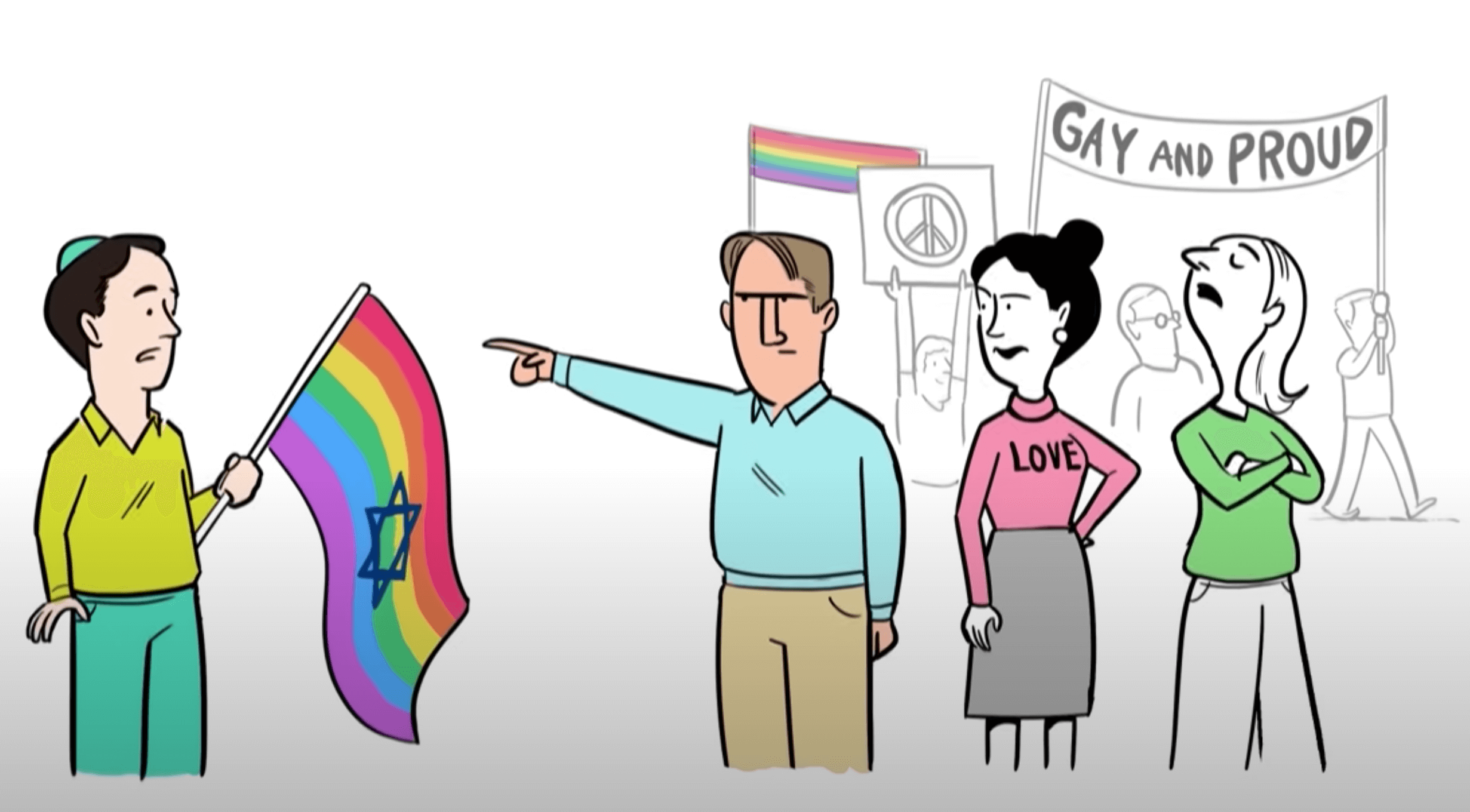

One animated video that Shine A Light promoted on social media shows a Jewish man being turned away from an LGBT Pride march, for example.

At the same time, Shine A Light — like progressive Jewish groups including T’ruah, Bend the Arc and IfNotNow, all missing from the coalition — also points out the connections between antisemitism and other bigotry. In one public service announcement, the narrator ticks off examples of antisemitism on the right — invocations of “dual loyalty,” “Soros” and “globalists” — and some associated with the left, like referring to Jews as “genocidal occupiers” and “Benjamins,” a reference to Rep. Ilhan Omar’s controversial comment about the Israel lobby. Shine A Light also shows special concern for the affluent, listing “gentrifier” as an antisemitic slur and suggesting that unchecked antisemitism could lead to protests against Wall Street.

“Here’s the thing, it may start with the Jews — but it never stops with them,” the narrator says in the ad, which ran on national television in November and December.

Friction in the coalition

Shine A Light has no full-time staff. For corporations who want to help employees understand antisemitism, the group suggests working with the Brandeis Center, which built its reputation launching legal challenges against universities over activism targeting Israel, and Project Shema, which states in its workplace training materials that “85% to 95% of Jews on earth” are Zionists.

In calling anti-Zionism — opposition to Israel as a Jewish state — antisemitic, the project is aligned with most of the American Jewish establishment. But it’s not clear how much of the Jewish public holds this view, and some prominent academics and organizations like T’ruah, the liberal rabbis group, have pushed back and tried to carve out wider space for activists who criticize or even boycott Israel.

Shine A Light not only considers anti-Zionism a form of bigotry but argues that some common left-wing critiques of Israel are also antisemitic.

“Accusing Israel of colonialism and apartheid quickly moves to the accusation Jews have dual loyalty or use money to control politics,” the narrator says in one of the project’s videos. “While it’s become commonplace to call Israel an ‘apartheid state,’” she continues, “it’s also a lie engineered to delegitimize Israel and Israel alone.”

A 2021 poll by the Jewish Electorate Institute found that 25% of American Jews believe Israel is an apartheid state, while 28% view that claim as antisemitic.

Though Reconstructing Judaism is part of Shine A Light’s broad coalition, its Israel director, Rabbi Maurice Harris, said he does not agree with the group’s contention that accusing Israel of colonialism or apartheid is “automatically antisemitic.”

“For someone who is maybe Palestinian — and is expressing a Palestinian perspective on the conflict — I think that they should be heard out,” Harris said. “They could even be wrong — but you can be wrong and not be antisemitic.”

Several other members of Shine A Light’s coalition who advocate for a more narrow conception of antisemitism, including the Union for Reform Judaism and Eric Ward, a civil rights leader popular with progressives, declined to discuss the apparent discrepancy.

Ethan Katz, who like Ward is listed as an expert speaker on Shine A Light’s website, said he takes issue with aspects of how the group approaches antisemitism. Katz, who helped found the Antisemitism Education Initiative at U.C. Berkeley and last year chaired an Association for Jewish Studies task force on the issue, nonetheless said he was “honored” to be part of the campaign.

“To be sure, I have some disagreements about the way that they define antisemitism,” he said in an email. “But in the end, I think that the struggle against antisemitism is a crucial challenge that demands more collaboration, rather than further division, across the Jewish community.”

Strong ties to Israel

The close connection between Israel, Zionism and Jewish identity promoted by Shine A Light reflects the experience of the Kirsh family patriarch.

Nathan Kirsh, widely known as Natie, was born in 1932 in Potchefstroom, a small urban center 90 minutes outside Johannesburg, to parents who had immigrated from Lithuania. His dad worked as an ostrich-feather salesman before finding success in brewing.

In an interview seven years ago with the Museum of the Jewish People, Kirsh said that he and his three siblings encountered little antisemitism as children. “Antisemitism virtually did not exist,” he said. “It was a very comfortable and good environment to grow up in.”

The 15-minute conversation appears to be the most Kirsh has publicly discussed Israel and Judaism. It was in 2016, just as resurgent antisemitism was becoming a serious concern in the U.S. but well after it had manifested in Europe and South Africa, where Kirsh spends much of his time. Yet he did not seem worried about it.

“The Jewish people, in my opinion, have never been in a stronger position as a people,” he said.

He was, however, concerned about Israel’s security, and recalled schoolmates who traveled to fight in Israel’s 1948 War of Independence. “To say that Israel is not threatened is wrong,” he said. “It’s been threatened from the day it started.”

Kirsh, who was a member of the Labor Zionist youth movement Habonim Dror, said in the interview that he keeps kosher but does not otherwise consider himself observant.

South Africa’s Jewish community has historically been one of the most staunchly Zionist in the world, and Israel maintained close economic ties with the country throughout apartheid. Kirsh was part of this economic partnership, when in 1984, while living in Johannesburg, he bought a perimeter-defense company, Magal Security Systems, from the Israeli government.

Years later, starting around 2010, Kirsh drew the ire of pro-Palestinian activists over Magal having received more than $40 million in Israeli government contracts starting in 2002 to build barriers dividing Israel from the West Bank and Gaza. Kirsh owned the largest share of Magal until 2014, when he sold 40% of the company; he retains a 5% stake.

Most of Kirsh’s holdings are not public, but records show that he has other investments in Israel, including a biotechnology firm designing a product to cure blindness.

Kirsh’s prolific philanthropy has also included major investments in Israel and Jewish causes. While growing his South African businesses, Kirsh began carrying a note in his wallet with a quote from Maimonides stating that the highest form of charity is to make a person self-reliant.

He has provided interest-free loans to more than 700 Jewish and Arab entrepreneurs in Israel since 2008 and bankrolled a computer-training program for yeshiva students. Kirsh was also a key donor to a film school in Jerusalem.

Yet most of his giving has focused on southern Africa. Kirsh had moved his family from Potchefstroom to rural Eswatini — formerly Swaziland — in 1960, when he was 28. There, he won exclusive control over the corn market from the British colonial authorities.

His daughter Wendy Fisher recalled that the family had a tap in the garden outside their home, which was up a hill from a village of mud huts that lacked running water. “It was only natural that villagers came to retrieve fresh water from our tap,” she said.

Kirsh has, over the decades, funded 11,000 small businesses in Eswatini — a country Kirsh calls his “fourth child” — and donated computers to nearly 150 of its high schools. Kirsh has also donated $8.8 million to the University of Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, his alma mater, and has supported his old high school.

He brought his love for Eswatini and Israel together two years ago, when he financed a COVID-19 vaccine campaign by IsraAID, the Israeli humanitarian aid organization, in Eswatini. “There are the blinds and the cripples and this and that and the next thing,” Kirsh said. “You have no choice but to give.”

It’s harder to track Kirsh’s donations in the U.S. While the family’s contributions are often branded as coming from “Kirsh Philanthropies” or the “Kirsh Foundation,” both seem to refer to Ki Philanthropies, a corporation registered in Delaware that is not required to share financial information. Marc Gross, an attorney whose LinkedIn profile states that he helped the Kirsh family office establish a presence in New York two years ago, referred to the entity as a “$150 million philanthropic group.”

Shine A Light is also part of a private company called Aston Investment Holdings Limited, which is based in California and has little public footprint outside the project.

Before Shine A Light, Kirsh helped fund several Israel advocacy projects, including the Britain Israel Research and Academic Exchange Partnership, meant to combat academic boycotts, and the Jewish People Policy Institute, a think tank where Fisher, one of his three children, sits on the board. Kirsh and his wife, Frances Herr, were credited in the introduction of a 2018 report by the think tank that outlined the danger to Israel posed by the apartheid claim.

“Its end goal is to turn Israel into a ‘pariah’ state isolated from the world, much like apartheid South Africa,” wrote the report’s author, Michael Herzog, who is now the Israeli ambassador in Washington.

Apartheid business

Kirsh, of course, had experienced that isolation firsthand.

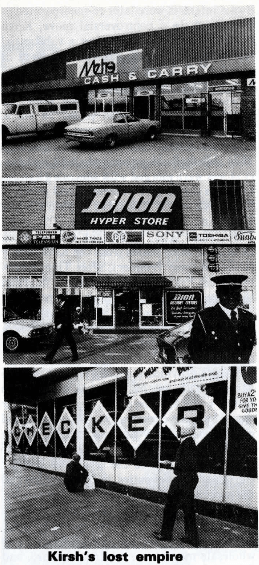

At the height of his business in South Africa during the early 1980s, he controlled one of the largest corporations on the Johannesburg Stock Exchange. Kimet employed 40,000 people across several of the country’s most famous retail stores — Checkers, Dion’s, Russell’s and Union Wine — and was responsible for 12% of all consumer goods sold in the country.

But Kirsh’s attempt to keep growing his empire ran into a wall in the 1980s, as international pressure on South Africa to end its racist apartheid system — which collapsed in the early ’90s — made it difficult to secure financing for big deals. Once known as the “daring dawn raider” of the stock market for his aggressive acquisition of rivals, by 1986 he was facing a hostile takeover of his own businesses after a partnership with a South African mega-corporation went south.

Kirsh made a fortune under apartheid. He took advantage of economic opportunities created by the government’s racist policies, and moved his company’s operations to avoid the impact of international sanctions aimed at apartheid. But like many in the business community at the time, Kirsh never seemed entirely at ease with the country’s political system — believing, if nothing else, that it would ultimately lead to a Black rebellion that would be bad for business — and he occasionally spoke out against government policies and white conservatives.

Profiles of Kirsh from his heyday in South African business describe him as “a whirling dervish” with a “brooding, restless quality” and “brilliant financial mind.”

“He’s fit, eats sparingly, and carries no surplus weight,” Hellouise Truswell wrote in Business Day, a South African newspaper, in 1983. “This is hardly surprising, as he plays a grueling hour’s squash every day while many others are at a three-martini business lunch.”

After his empire crumbled in 1986, the Financial Mail’s cover depicted him as Icarus, wings melted by the sun and plunging back to earth. Inside the magazine’s pages, Kirsh would say that he decided not to fight the takeover of his company because political events in the country had left him “demotivated.”

“I thought to hell with you,” Kirsh told the South African Business Times in 2011 of his decision to leave South Africa. “What do you want to break my arse for when this country’s going to hell anyway? I’m getting the hell out of here.”

Kirsh explained to a group of London Business School students in the same year that he had been convinced a popular revolt against apartheid was going to destabilize the country and make it impossible to do business.

“This is going to end up as a revolution,” he recalled telling F.W. DeKlerk, the leader of South Africa’s governing National Party, during the 1980s.

But alongside these misgivings, Kirsh made a lot of money off the region’s racist laws. The crown jewel of his South African businesses, Metro Cash & Carry, responded to an apartheid policy that banned white businesses from operating in the destitute townships where Black people were forced to live by establishing wholesale outlets on the edge of these areas. The outlets supplied thousands of small stores run out of homes and roadside booths. The shops Kirsh supplied, beginning in 1970, had higher prices than the Checkers stores he owned in white areas, but were some of the only places Black consumers could conveniently purchase essential goods.

By 1981, Metro was clearing the equivalent of $2 billion in today’s dollars.

The fall of apartheid in 1990 would doom Metro’s business model, but by that point Kirsh had already sold the firm under duress and left the country with a reported net worth of $25 million. He went on to replicate Metro’s success in New York City with Jetro and Restaurant Depot, identifying a lucrative niche supplying food to small retailers like bodegas and diners overlooked by larger wholesalers. He grew Jetro to generate $6.5 billion in annual revenue in 2012, and spread his investments around the world. He owns Tower 42, one of the tallest skyscrapers in London, and Jandakot Airport in Perth, Australia.

Shine A Light did not respond to multiple inquiries about Kirsh’s business dealings during apartheid made through ID, the celebrity public relations firm it hired to promote the project.

Kirsh’s critics — some antisemitic

Kirsh occasionally criticized the apartheid regime, including in 1984, as South Africa bowed under the weight of international opprobrium and strikes. Kirsh told Business Day that the “unfortunate consequences” of the government’s economic policy “will fall most heavily on the poor and unemployed — in the South African context, on the Blacks.”

In Eswatini, he used his considerable influence to support the country’s independence from Britain in 1968. John Daniel, a dissident South African academic who relocated to Eswatini, grouped Kirsh with the “more progressive elements amongst the settlers” in that country.

But critics note he also used opened factories in Eswatini to avoid international sanctions on South Africa, with his company being one of the first to open a new factory in the country in 1985 as export restrictions hit South Africa. Other corporations quickly followed Kirsh’s lead.

“There are opportunities that come out of sanctions,” he later told Bloomberg. “Sanctions can be broken.”

Kirsh also took advantage of apartheid-era incentives from the South African government in 1983 to build factories near the “bantustans,” regions created to deny Black South Africans citizenship.

Kirsh and Issie, one of his two brothers and a broadcasting magnate, had also started an independent radio station in 1980 that initially pursued a conservative political line. The station also considered banning Stevie Wonder’s music after he dedicated his 1985 Academy Award to Nelson Mandela, and declined to play “Sun City,” a famous song calling for a boycott of the eponymous South African venue, in part because the company that owned the resort had a stake in the station.

In recent years, Kirsh has made headlines for his involvement in contemporary South African politics, reportedly bankrolling a minor opposition party led by a former anti-apartheid activist and paying for the legal defense of a controversial former prosecutor. That has brought new scrutiny of his record during apartheid, including criticism tainted by antisemitic tropes.

In 2014, the South African Communist Party condemned Kirsh as “a pioneer of global capitalist puppetry.” The following year, the Mail & Guardian, a leading weekly newspaper, included prominent references to Kirsh’s Jewish identity in an article spreading the conspiracy theory that he was secretly bankrolling a Marxist political party in order to undermine the South African government.

David Saks, associate director of the South African Jewish Board of Deputies, lamented to the South African Jewish Report that Kirsh had joined the supposed “pantheon of malevolent Jewish capitalists,” alongside other notable families like the Rothschilds and Oppenheimers who are also the subjects of antisemitic conspiracies.

Kirsh seems to have taken note. In his interview with the Museum of the Jewish People, which took place shortly after the attacks against him in South African media, Kirsh said he supported the museum because it was a way to showcase the contributions Jews had made to societies around the world.

He wanted to “get away from the notion that one reads so often in the press that the Jews take from a community, that the Jews exploit a community, that the Jews get rich at the cost of a community,” Kirsh said, “when the truth of the matter is the other way around.”

It is unclear how much involvement the nonagenarian, who initiated a transition plan for his business operations several years ago, has had in the precise direction of Shine A Light. But it’s hard to miss the parallels between his own life and the project.

Kirsh bonded with Israel at a young age and has long had an ambivalent relationship to progressives in his native South Africa, historically wary of their revolutionary instincts and, more recently, savaged by left-wing criticism that was tinged with antisemitic tropes, even as he has expressed some sympathy for their political beliefs. It’s a set of experiences that parallel how the Jewish establishment — working closely with wealthy donors like Kirsh, whose philanthropy can conjure new campaigns from scratch — has approached antisemitism in recent years: with an eye toward protecting the connection between Jews and Israel, and wariness about whether the left can really be trusted.

Shine A Light’s organizers are currently reviewing the December campaign and preparing for another one later this year, perhaps with some changes based on feedback from members of the coalition.

“I can’t tell you now what Shine a Light 3.0 is,” Maisel said on the podcast. But, she added, “The underpinnings of the point and the values of Shine A Light are going to stay exactly the same.”