A fight over Jewish identity is going to determine America’s future

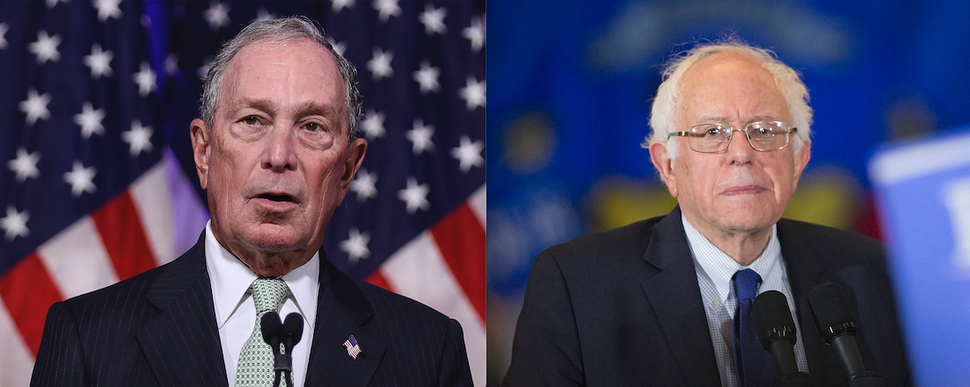

Newly announced Democratic presidential candidate, former New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg speaks during a press conference to discuss his presidential run on November 25, 2019 in Norfolk, Virginia. The 77-year old Bloomberg joins an already crowded Democratic field and is presenting himself as a moderate and pragmatic option in contrast to the current Democratic Party’s increasingly leftward tilt. In recent years, Bloomberg has used some of his vast personal fortune to push for stronger gun safety laws and action on climate change. (Photo by Drew Angerer/Getty Images) Image by Getty Images

Two Jews, one Oval Office: The plot is wild, too weird for even Roth or Bellow. And yet, as the Democratic primary revs into chaotic high gear, polling is increasingly presenting American Democrats with two septuagenarian Jews, Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders and former New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg, facing off for the right to depose President Trump.

It’s the billionaire vs. the socialist, the moderate vs. the leftist. But Sanders and Bloomberg don’t only have radically different plans for the future; they embody two irreconcilable stories about the past, two wings of a Jewish house divided against itself. The fact that this contest is increasingly ugly (the two spent the long weekend sparring on Twitter) should come as no surprise: Sanders and Bloomberg are each other’s doubles, reflections mirrored and reversed.

The Bernie-Bloomberg choice is nothing short of a choice between two versions of American Judaism — but it’s the future of America that will be decided.

Ari Hoffman | artist: Noah Lubin

On the one hand, you have Bloomberg, the grandson of immigrants, who made his mark on Wall Street. There he innovated, took a moderate risk, and made a fabulous amount of money.

Not a religious man, Bloomberg’s boosters as well as his detractors label him an institutional one; he’s a member of flagship Reform congregation Temple Emanu-el and a generous giver to institutions Jewish and non-Jewish, both here and in Israel. And when it comes to solidarity, it’s Israel that has his heart; many Jews still recall his flight to Tel Aviv amidst rocket fire during the 2014 Gaza War as the type of thing they wished they could have done, if they were able to charter a plane.

In other words, Bloomberg represents the most prominent example of the great story of Jewish success in America in the second half of the 20th century. He stands first and foremost for the proposition that America has been good to the Jews, and the Jews have been good for America.

On the other hand, you have Sanders, who represents a different American story. The son of an immigrant, Sanders grew up working class in Brooklyn. As an adult, he found his promised land in woodsy Burlington. With crisp air to breathe and the tenements at a healthy distance away, Sanders committed wholeheartedly to the socialism that was the hallmark of a different kind of Jewish American identity, toiling away as a politician and servant to the people, often under financial duress; Sanders didn’t become a millionaire until he sold a book after the 2016 election.

Sanders gives voice to that part of Jewish history that has always disdained the status quo, that sees fairness as a cause so urgent that you feel it pulsing, urging, and provoking every hour of every day. It’s an authentic strain, one that links him with the Yiddish Bundists who thrived between the wars in Europe and took root in this soil after the great migrations of Jews, transforming into a passionate commitment to fighting for civil rights and combating inequality.

If Bloomberg’s is a Jewishness mired in success, Bernie’s is a restless Judaism, prodding, critiquing, and agitating for a better world. It has its eyes open to injustice, and its arms linked in solidarity with others, often less fortunate. It’s a Jewishness focused on universal values, rather than particular ones. Thus, though Sanders famously volunteered in a kibbutz in 1963, he honeymooned in the Soviet Union when it was a crime to practice Judaism, and has become one of the most vocal critics of Israel in the U.S. government, even appointing as surrogates people considered to be anti-Semitic by much of the Jewish community.

Much — but not all, for just as Bloomberg has his Jewish supporters, Sanders has found a deep well of support among a resurgent anti-Zionist Jewish left, who see in him the embodiment of their own Tikkun Olam-oriented Jewishness.

In other words, Sanders and Bloomberg don’t represent just two competing models of Jewish history, but two models of Jewish identity, and thus, two models for a Jewish American future. The Bloomberg future is one where support for Israel remains at the center of the agenda, and where the great and the good, or just the very wealthy and well connected of the Jewish community continue to plot its course from Upper East Side parlor meetings and Jerusalem rooftops. It will be underwritten by checks cashed with the conviction that Jews are both mighty and imperiled and must use their might to make themselves less imperiled. It is more of the same, only much more of it.

The Bernie future is a swerve into a new dimension. It would make the historical footnote of Jewish involvement in the radical left into prologue for a new posture of full-throated commitment. Largely unburdened by synagogue and Zionism and energized by a new sense of community, Bundism 2.0 would reopen Jewish politics in a way not seen in generations. Sanders is a real paradigm shifter, and in his hoarse call for reordering there are echoes of the Jewish audacity to not only fix the world, but reimagine what it might still become.

It’s a big decision. But it’s not just the future of the Jews at stake. Bloomberg and Sanders are competing to become president of the United States; Jews stand ready to define the politics of the most powerful nation on earth; we’re not in the shtetl anymore.

Ari Hoffman is a contributing columnist at the Forward.