Despite childhood bullying, I’m proud of my Indian Jewish identity

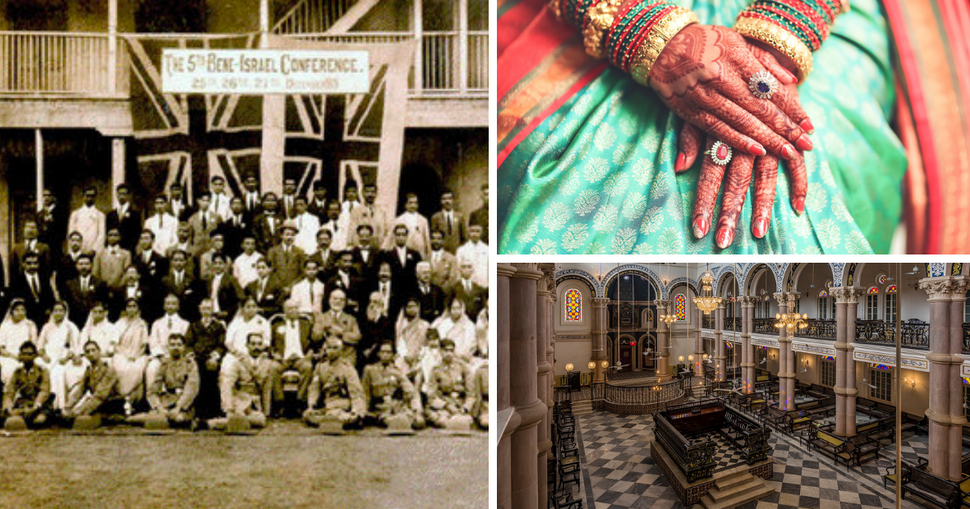

L-R, clockwise: the 5th Bnei Israel Conference held in Mumbai, Dec. 1921; an Indian bride’s hands covered in henna; the interior of Magen David Synagogue in Kolkatta, India. Photo-illustration by Jake Wasserman

I’ve always viewed myself, growing up with an Indian Jewish mother, as an experimental new dish added to the menu of life. Add one cup of challah, another cup of sari’s and chutney, a dash of Germanic roots and blend vigorously until you get one enthusiastic and occasionally confused me.

I have not always appreciated my own mixed Indian-Sephardi flavor. Growing up as a mixed Indian Jew in the Southwest, I experienced two different cultures: the American Jewish experience and the Indian experience. I would go to the Ashkenazi Yom Kippur services (there were no Sephardic shuls in my area) dressed in white, reciting the prayers in a repetitive fashion until the break-fast, when my mom, grandma and I would drive rapidly to the local south Indian restaurant and inhale a few hundred samosas with chana masala.

When I was 15, I begged my grandmother to make her storied Indian lamb chops that I’d never tasted. She told me that the dish takes time to make, and that she would save them for a special occasion. After Rosh Hashanah services that year, my mom, grandma and I went to my grandmother’s apartment; there, on the table, were my grandmother’s famous lamb chops.

The aroma was so beautiful and the chops themselves were delectable. My now vegetarian body scoffs at the smell of meat, but if I smelled those lamb chops again, I would eat them in a heartbeat.

Despite having these little splashes of my culture woven into my life, growing up, I treated both my Jewish side and my Indian side as compartmentalized and separate aspects of my life. I could not imagine a space in which I would be able to fully appreciate my combined Indian and Jewish heritage.

On one occasion, when I was in first grade Hebrew school, I was approached by my religious schoolteacher who asked me whether my grandmother would be interested in giving a presentation on the Jews of India. My grandmother Elizabeth, who was an avid speaker and advocate for the Jews of India, was more than willing to speak on this topic.

She came in with a sari and started draping its long, silky fabric around me, explaining to my classmates that this garment is what she, and other women in her region, wore as everyday wear — except on Yom Kippur, when she wore a white kasavu sari embroidered with gold on the bottom.

My grandmother explained how she grew up in the Pune region of the Maharashtra State of India in a Jewish family, who emigrated from Iran many centuries ago. She said that she attended the Jewish Girls School during the week, and on the weekends, Magen David Synagogue in Kolkata, a historic synagogue originally established by Baghdadi Jews.

She herself was a Bnei Israel Jew, a group of Jews said to be part of the “10 lost tribes” exiled from modern-day Israel and, as a result, scattered to areas throughout Europe and Asia. In my family’s case, they immigrated to Iran and wound up settling in India.

Looking back on the interaction, I am surprised how open-minded, thoughtful and respectful my first grade classmates were when my grandmother was giving her presentation, because later on, I would learn that not everyone is as open-minded as children in first grade, whose identities are still being molded by the world. This experience was the first time I saw my identity truly seen and accepted by those around me.

Until eighth grade, I attended a public charter school where the children and faculty made it seem like they had never encountered a mixed child before. Being an Indian Jew meant I would leave class on High Holidays and show up to class bringing the aromas of Indian cooking in with me.

Most of my teachers would make subtle remarks I now recognize as microaggressions. When I left school early for High Holiday services, my teachers would say things such as, “Leaving so early again?” or, “I wonder where you were yesterday?” despite knowing exactly where I was. I was already being verbally bullied in middle school for being different, which the teachers were aware of, but they continued to make pointed comments highlighting my difference, ensuring that my classmates and I knew I was an outsider.

Some teachers would even ask me directly “What are you?” or “Where are you really from?” in front of the entire class. My classmates would laugh, and the teachers would smirk at my discomfort. The faculty’s insensitivity only fed the bullying I experienced from my classmates, which continued until I graduated.

The critiques about my identity followed me to my extracurricular activities as well. In seventh grade, I participated in the robotics club where I would receive underhanded remarks from the teacher that I was not excelling to the “standard” they were “used to” despite my performance at previous robotics competitions. They seemed to be under the assumption that because I was of mixed race, I would not be able to perform up to the level as my fully Indian or South Asian classmates. As a result, I was kicked out of the club one week into robotics.

In that same grade, after trying robotics, I moved on to soccer, a sport I played well. I was told by the soccer coach that maybe I should be “participating in something different,” not giving me a proper explanation as to why I would be a permanent bench warmer. All I knew was that I did not fit the mold of the stereotypical soccer girl at the school, who had blonde flowing hair. All I understood was that I was constantly sitting on the bench, to the point where my mom had to ask my coach why I wasn’t playing. I was not surprised when the coach offered no real reason and, as a result, my mom asked me to drop the sport.

Where was I meant to go? I felt like I was somehow falling short of the Sarah that the outside world expected me to be.

I did not fit the mold. I was the only Jewish Indian, and the only Jew, in a school swimming with people who did not understand what on Earth I was.

It wasn’t until I went to a high school where everyone practiced Judaism that I felt at home. Despite being the only Indian student in my class, I still felt a sense of community. I knew I could express my Indian heritage without ridicule, dirty looks and stereotypes because, at the end of the day, we were united by our Judaism.

Since leaving high school, I have struggled to find my place within the Jewish community as a person of color. I questioned whether I, as a Jew who grew up in an Ashkenazi synagogue, should be going to a Sephardic synagogue. The truth was, no matter which synagogue I went to, I did not fit in, because I was not the stereotypical Sephardic Persian Jew nor was I the Ashkenazi European Jew.

When I started college, the Sephardic club on campus questioned whether I really was Sephardic, referring to my lighter skin tone and my toned-down European features. It made me rethink how I viewed that community and whether I fit that mold. I questioned how I could integrate my culture and my religion peacefully into my life.

Today, I am still searching for a synagogue where I feel I belong. In the meantime, I continue to learn more about my religion as well as the texts that go along with it, while also attending Hindu holidays, such as Holi or Diwali, (holidays which Bnei Israel Jews do not attend, but do celebrate on a superficial level in India) in order to integrate both halves of my identity cohesively into my life.

Over the years, I have learned how to accept my two halves, and quite frankly, I am still learning to accept both. Something that has been unwavering, however, throughout my life thus far is that I am proud of my roots. I know that the more I express my light and my story, and other mixed Jews of color and Jews of color express their stories, the more open and understanding the world will become of our beautiful mixed race.

To contact the author, email [email protected].