My dad stormed Normandy on D-Day — and relived the fight against Nazis every night

My father parachuted into France and fought during World War II on a personal mission to defeat Hitler

View of Allied troops from a transport vessel, among them medics with stretchers over their shoulders, as they wade ashore during the invasion of Normandy, France, in June 1944. Photo by Underwood Archives/Getty Images

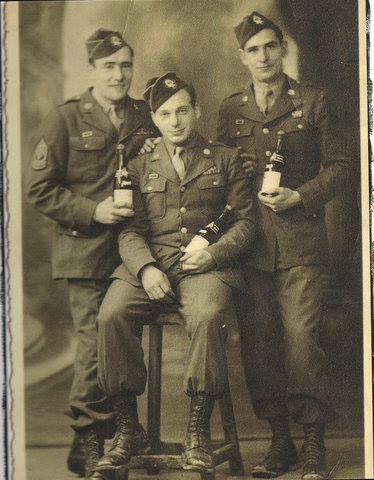

My father was a paratrooper in World War II, part of the 101st Airborne’s famed parachute division. He jumped from the fifth plane out of England a few minutes after midnight on D-Day, June 6, 1944.

He was the son of Russian Jewish immigrants and an eighth grade dropout who worked in the Garment District, and his experiences as a soldier were the most important things that ever happened to him.

He relived those experiences every night at the dinner table. We didn’t know the term PTSD when I was a kid, but looking back, it seems to me that he lived every day like it was his last. I guess that was his way of coping with the memories of jumping out of an airplane onto enemy soil, not knowing if he’d live to see another sunrise.

It might sound strange to modern parents who fret about exposing their kids to stories about war and other terrible things, but I loved hearing my father’s battle tales. I was in his thrall every night as I pushed my green peas into my mashed potatoes while hearing him describe taking out a nest of German machine guns or hunting down Nazis in the dark.

Dad was a hero, larger than life, and I was intensely proud of him growing up. And while I sometimes had childhood nightmares of Nazis chasing me, I wouldn’t have traded those dinnertime stories for anything.

I knew what it was like to kill a Nazi soldier at point-blank range by the time I was in third grade. I knew that my father threw his dog tags away because they listed his religion, and he figured if the Nazis ever got him, they’d “rip his balls off.” (I didn’t exactly know what that meant, but it didn’t sound good.)

And I knew why he’d enlisted in World War II rather than waiting to be drafted. His parents had come to the United States to escape pogroms and poverty. While Dad was an utterly secular Jew, he wanted to help defeat Hitler — both to avenge his people and to thank the country that gave his family refuge.

The D-Day invasion of Normandy was a turning point in the Allied effort to defeat Hitler. After taking part in the liberation of France, Dad and his buddies were deployed to the Netherlands as a part of Operation Market Garden, which was depicted in the film “A Bridge Too Far.”

In December, they holed up in Bastogne, Belgium, for the Battle of the Bulge, where General Anthony McAuliffe famously replied to Nazi demands for a U.S. surrender with one word: “Nuts!” (Dad claimed what the general really said wasn’t printable, but he didn’t elaborate.)

At some point as they fought their way across Europe with the Allied forces, his unit took custody of a group of German prisoners of war. One of the other U.S. soldiers decided to taunt the Nazi commander with the fact that my dad, his captor, was Jewish. The German spit at him and called him a schwein — pig.

My father said he took out his gun and shot the man dead on the spot. He could have been court-martialed for killing a POW, but told me that nobody reported it.

Instead, Dad earned two Bronze Stars, two Presidential Citations and a Purple Heart for a bullet wound that crippled his right arm. Coming home, he smoked like a chimney, gambled away every cent he earned, and had a lifelong fondness for calvados, the apple brandy that Normandy farmers offered the soldiers who liberated them.

As I got older, I didn’t always agree with Dad’s politics; among other things, he supported the U.S. war in Vietnam. But by way of explanation, he ended every story with the same refrain: “Your country is like your mother. Your mother, right or wrong. Your country, right or wrong.”

For a son of immigrants whose family would likely have been murdered by Cossacks or Nazis had they not gotten on a boat to Ellis Island, it was a sentiment I could understand.