I rallied for the survival of Israel in 1967 but now I worry about its future

The occupation has tempered my confidence in Israel’s survival as a democratic homeland for the Jewish people.

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

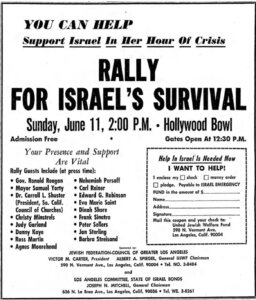

The first time I went to the Hollywood Bowl was 55 years ago, on June 11, 1967.

As a 14-year-old, I went to the Bowl with my family for the “Rally for the Survival of Israel,” a massive demonstration of solidarity with Israel after the Six-Day War.

Although I would have preferred to see the Monkees, who performed at the Bowl only three days earlier, the rally for Israel was no less exciting. The amphitheater overflowed with people. The stage was filled with celebrities like Frank Sinatra, Joey Bishop, Peter Sellers and Barbra Streisand.

After three of Israel’s four neighboring Arab states had amassed armies on their borders, Israel preemptively launched an attack and defeated them, capturing the Sinai Peninsula from Egypt, the Golan Heights from Syria and the West Bank of the Jordan River — including East Jerusalem — from Jordan.

As a Jew, I felt proud. Secure. Most importantly, I felt that justice had prevailed. Now, I am deeply troubled about Israel’s long-term security and moral standing in the world.

The Hollywood Bowl rally was a decisive moment personally as well, in a pivotal year for the development of my political identity. It took place the year the Beatles sang “All You Need Is Love,” and the year Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his anti-war sermon at Riverside Church in New York City. King’s address was followed by a discourse from Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel, a professor at the Jewish Theological Seminary and a leading religious voice against the Vietnam War. Two years earlier, Heschel and King had marched together from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama.

Support for Israel, fighting for civil rights, and opposing the war in Vietnam were seamlessly connected for me as expressions of my Jewish ethical code. My parents were Holocaust survivors who immigrated to the U.S. This confluence also helped me feel like I was on the right side of history, aligned against bigotry and hate, and fighting for justice and equality.

In the years that followed, through high school, college, and ultimately in my career as head of the New Israel Fund, Israel Policy Forum and other groups working to support a Jewish and democratic Israel, I dedicated myself to these causes. In solidarity with other Americans, I marched to promote equality and denounce the Vietnam War. Together with other Americans, I advocated to save Soviet Jews and for Israeli-Arab peace — from Camp David to Oslo as well as new proposals for a confederation of Israel and Palestine.

But things are different now. The sense of common purpose that I felt during those years has dwindled. By moving away from the principles on which it was founded, Israel is exposing itself to opposition from liberals and progressives who have always supported it.

I still believe in those principles. My love and support of Israel have not diminished, but it is getting harder to justify its actions.

Ironically, the seeds of my distress about Israel were planted 55 years ago. Israel still occupies the West Bank and the prospects for Israeli-Palestinian peace are dim. The prime minister of Israel, who has long opposed the two-state solution, won’t so much as meet with the head of the Palestinian Authority. There are Israeli leaders, even including some active military officers, who vocally support a permanent occupation and the effective annexation of the West Bank.

Today, it’s hard to feel proud of Israel, or that justice is prevailing in the only Jewish state. As misguided as the Palestinian Authority’s leadership is, I cannot defend Israel’s eviction of over 1,000 Palestinians from their homes in the West Bank. As reprehensible as Palestinian terror attacks against innocent Israelis are, I cannot countenance Israeli settler attacks on Palestinian villagers nor ultranationalists marching through the streets of Jerusalem chanting “Death to Arabs.”

It is also harder to feel secure. The sense of confidence that I had in 1967 had a lot to do with how integrated I felt into American society. But the coalitions that seemed intuitive then are now at risk of decay. Progressive support for Israel has diminished. Black Americans’ solidarity with Palestinians has grown. Jews like myself who are socially progressive and support the existence of Israel but are against the occupation increasingly find themselves to be politically homeless in this new reality.

Unequivocal supporters of Israeli government policies have launched massive campaigns to defeat progressive candidates for political office. Some progressive Democrats who criticize Israel have been labeled anti-Israel for advocating the same policies for peace and security that senior Israeli political and military figures have promoted. I don’t agree with everything these progressive lawmakers promote, but I do believe that the occupation has eroded support for the only Jewish state. And it has heightened ideological divisions on the conflict to the point where a constructive debate about how to rectify the situation is nearly impossible.

Some Democrats have accused their colleagues of antisemitism. A letter signed by four Jewish Democratic House members last year even invoked the Holocaust to denounce the characterization of Israeli policies as apartheid. Instead of speaking as a unified, liberal Jewish community, the American Jewish Diaspora is increasingly fractured.

The late Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin once warned that maintaining an occupation would lead to apartheid. In the early 1990s, I worked with Rabin to promote his vision of peace and security in my role as president of Israel Policy Forum. Rabin was a fierce warrior for Israel and the Jewish people. I don’t believe he would have exploited antisemitism to counter critics of Israel, even the harshest among them. He would have challenged Israel’s opponents on substance, having no patience for empty rhetoric.

Using accusations of antisemitism to stifle debate about Israel’s policies is not only wrong but also short-sighted and dangerous. It diverts the debate away from the substance to whether something is — or is not — antisemitic. If we want to condemn opponents of Israeli policies for being antisemites, we should denounce Jordanian shopkeepers for displaying Mein Kampf in their windows and punish pro-Palestinian assaults on Jews in the U.S. as hate crimes.

Misguided accusations of antisemitism also distract from addressing actual instances of anti-Jewish bigotry. The security guard at the entrance to my synagogue is not there to protect congregants against those who want to boycott Israel. He is there to prevent another Pittsburgh, or Poway, or Colleyville. Antisemitic incidents in the U.S. in 2021 rose by 60% from the previous year, and when every perceived slight is labeled antisemitic, I believe it dilutes the very real and pressing need to better protect American Jews.

Weaponizing antisemitism also hurts Israel. Toxic environments leave no space for debate. Without an open debate about Israeli policy, the occupation will metastasize.

If that happens, the prospects for resolving the Israeli-Palestinian conflict will fade into the darkness, along with the feelings of pride, security and justice that I had on this day, 55 years ago, at the Hollywood Bowl.

To contact the author, email [email protected].