Jewish New Yorkers should be concerned about the monkeypox vaccine rollout

The monkeypox surge is only the latest example of marginalized peoples’ needs being ignored by the government

People wait in line to enter the Chelsea Sexual Health Clinic for a monkeypox vaccine on July 8, 2022 in New York City. Photo by Michael M. Santiago/Getty Images

As I stood outside of a Harlem health clinic, waiting to get a monkeypox vaccine, a Black person approached a registration attendant, asking if he could get an appointment. The attendant told him he needed to register online first.

He’d tried to, he explained, but the website crashed on him at the critical moment of sign-ups, and he didn’t have another hour to keep clicking.

She turned him away as the line of white gay men with appointments grew longer.

That’s how, in predominantly Black and brown Harlem, a queue of white queer men — individuals who worked jobs that allowed them to hit “refresh” for two hours in the middle of a Tuesday — were the only people able to get the shot.

Over social media, the NYC Health Department announced that a small, new batch of monkeypox vaccine appointments would be available online. On July 12, thousands of people logged on to the same (crashing) website at exactly 1 p.m., hoping to get one of the mere 1,250 appointment slots for all of New York City. I spent an hour anxiously refreshing the page to no avail. Luckily, I had a friend on another computer sign me up successfully for a slot — there are currently no monkeypox vaccines available.

In a city that boasts an LGBTQ+ adult population of over 700,000 people, monkeypox vaccination shortcomings are causing alarm during key moments required to stop the spread. As a queer transgender Jew, I feel particularly sensitive to how the state allocates care in relation to bodies, and whose bodies are prioritized by the system to receive care. The monkeypox surge is only the latest example of marginalized peoples’ needs being ignored by the government.

The monkeypox outbreak in the United States is a health crisis that affects everyone, but currently, cases have been spreading fastest among NYC’s queer communities, with gay men at the highest risk of exposure. Monkeypox isn’t a sexually transmitted disease, but it can spread from body contact, exchange of fluids and touching fabrics that have been in contact with an infected person.

New York City was recently allocated 14,500 vaccines — 10% of the national total monkeypox vaccines available, despite having 32% of the country’s cases. The city currently is sponsoring eight pop-up vaccination clinics throughout the five boroughs, but all with extremely limited availability, requiring online sign-ups for appointments.

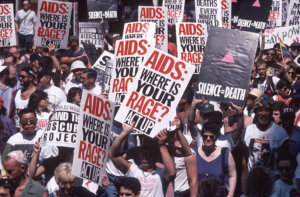

For New Yorkers, the ways that the city is mishandling monkeypox smack of the same homophobia and fear that haunted the AIDS crisis. When an illness is stigmatized or scapegoated on a particular population, not only is the general public less protected, but inequalities in access to medical care grow even more stark.

In Yom Kippur fashion, who lives and who dies (or becomes seriously ill) is a painfully relevant question — and we cannot afford to treat it as an arbitrary theological thought experiment. All public health officials in the United States should act with an awareness that without specific efforts to get treatment and resources to underserved communities, they’re all going to go to the white and wealthy.

I spend a lot of time thinking about demographics and the ways bodies get sorted by the state. Maybe my Holocaust education started a little too young, but there has always been something vaguely sinister to me about routine scrutinies such as passing through airport security, obtaining a driver’s license and filling out vaccine forms, with checkboxes distilling me into a set of categories. When you are not cisgender, this type of scrutiny and categorization related to one’s body can feel like an echo of the Nazi selections — some bodies being told to go to the left, the others to the right.

It might look just like paperwork, but I often wonder about where the information collected about our bodies goes and how it gets used. It’s no longer a secret that IBM was contracted by the Nazi Party to use its remarkable new information technology to do the work of genocide. With IBM’s punchcards and machines, the Nazis could parse through massive amounts of census data and create lists of Jews for internment, write efficient train schedules, keep track of ghetto statistics and run a fascist war machine with a bureaucratic smoothness the world had never seen.

Systems and algorithms are never neutral. Technology has the ability to connect us to lifesaving information and resources, just as it has the potential to be a tool of great evil. Regardless of conscious intent, it’s often during critical moments like these that the existing prejudices and inequalities in a society magnify, often with deadly results for the most vulnerable.

That’s why it matters that we take a good look at the structures facilitating the issue. After initial COVID-19 vaccine releases crashed every server, we should know better than to contract monkeypox vaccine sign-ups to third-party websites that aren’t prepared for such high volume activity. A lottery or rolling sign-up would’ve been infinitely more equitable, even if imperfect. Vaccine appointments need to be offered during evening hours, too, when those who work during the day can make it.

COVID-19 showed us the truth of the premise at the heart of every justice-based social movement: No one is safe unless we’re all safe. Jewish law teaches us to rebuke our household or our country when wrong’s been done. Jewish history makes that an imperative. Personal responsibility means speaking out against the systems causing damage and doing whatever we can to envision and implement repairs.

Until our cities have learned from the legacy of AIDS and COVID-19, the Jewish taxpayers of America aren’t exempt from demanding more equitable health care for monkeypox vaccines and every public health crisis that comes next.

To contact the author, email [email protected].

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

Now more than ever, American Jews need independent news they can trust, with reporting driven by truth, not ideology. We serve you, not any ideological agenda.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism you rely on. Make a gift today!

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Support our mission to tell the Jewish story fully and fairly.

Most Popular

- 1

Fast Forward Ye debuts ‘Heil Hitler’ music video that includes a sample of a Hitler speech

- 2

Opinion It looks like Israel totally underestimated Trump

- 3

Culture Cardinals are Catholic, not Jewish — so why do they all wear yarmulkes?

- 4

Fast Forward Student suspended for ‘F— the Jews’ video defends himself on antisemitic podcast

In Case You Missed It

-

Fast Forward In first Sunday address, Pope Leo XIV calls for ceasefire in Gaza, release of hostages

-

Fast Forward Huckabee denies rift between Netanyahu and Trump as US actions in Middle East appear to leave out Israel

-

Fast Forward Federal security grants to synagogues are resuming after two-month Trump freeze

-

Fast Forward NY state budget weakens yeshiva oversight in blow to secular education advocates

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.