Trump destroyed the guardrails against antisemitism — and there’s no going back

We used to ostracize public figures for even loose affiliations with antisemitism. Those days are long gone

Trump dismantled the fence that prevented anyone around the president — never mind the president himself — from saying anything that smacked of anti-Jewish prejudice. Photo by Joe Raedle/Getty Images

In September 1988, James Baker fired four members of an ethnic outreach coalition he’d recently established. Baker, then manager of Vice President George Bush Sr.’s campaign for president, made the move soon after a news story revealed their past associations with a variety of fascist or antisemitic organizations.

In one case, it wasn’t even entirely a first-degree association. Florian Galdau, a New York archbishop of the Romanian Orthodox Church, had been a loyal and zealous defender of that sect’s U.S. leader — a prominent, self-confessed activist during World War II of the Iron Guard, Romania’s wartime pro-Nazi movement. Galdau staunchly backed his superior, Valerian Trifa, during the Justice Department’s effort to deport him for lying about this past to gain entry to the country and obtain American citizenship.

The three other members of the American Nationalities Coalition included a Croatian American active in organizations that denied the Holocaust, a Catholic priest listed in Italy as a member of a neo-fascist secret organization, and a Republican activist who had served as a junior envoy to Berlin of Hungary’s pro-Nazi Arrow Cross regime during World War II.

As the reporter who broke that story, I recognized that the Bush campaign was acting in line with the Talmudic mandate to “build a fence around the Torah,” that is, to construct outer guardrails around the principles you hold dear.

In fact, Laszlo Pasztor, the erstwhile junior envoy, later actually expressed regret about his service. But like the others, he quickly found himself outside the fence that Bush drew, albeit belatedly, around his campaign. Jerome Brentar, the Croatian American, was gone within hours after the story hit; the others soon after.

A fence around the Torah

“You cannot expect any quicker action than that,” enthused GOP activist Marshall Breger, a former White House liaison to the Jewish community, who praised my news outlet, Washington Jewish Week, for exposing the blunder by his own side. Baker himself said in a statement accompanying his action: “There is no room for antisemitism or bigotry of any sort in our campaign.”

That claim may be worth some skepticism. It was the Bush 1988 campaign, after all, that also gave America the infamous Willie Horton TV ad, with its close-up of a scary-looking disheveled and scowling Black man convicted of murder who was allowed out on a weekend furlough program under the administration of Bush’s opponent, Massachusetts Governor Michael Dukakis, during which time he raped a white woman and knifed her fiance. The ad is today considered a classic in dog-whistle racism.

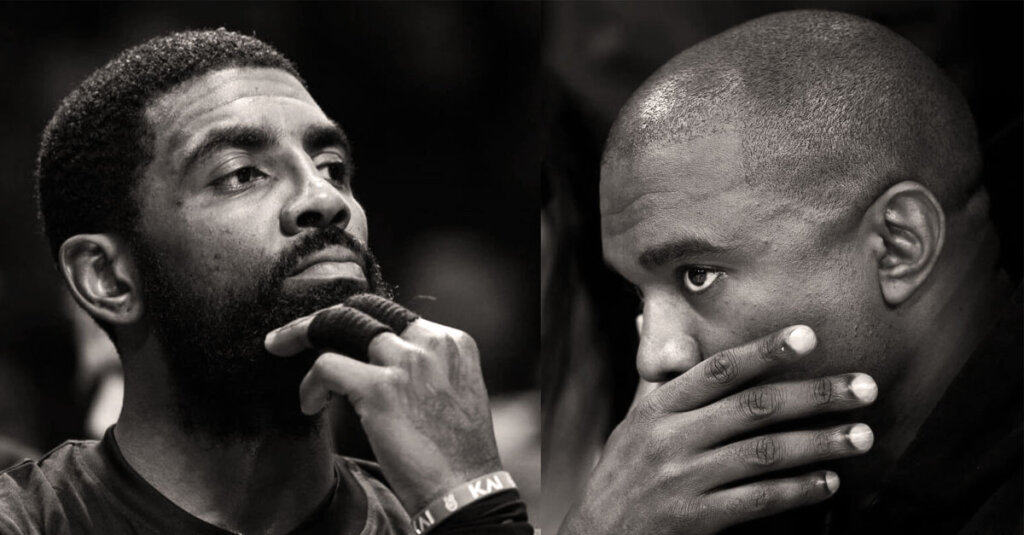

Despite this, the Bush campaign’s prompt and strong response to the antisemitism charges — with no claims of “fake news” — is something we might yearn for after the sclerotic and reluctant reactions recently shown by organizations such as Adidas (to Kanye West, who now goes mononymously by Ye), the Brooklyn Nets and the NBA (to Kyrie Irving) and by the GOP candidates Doug Mastriano and Blake Masters to Andrew Torba, a prominent Christian nationalist supporter with a record of anti-Semitic statements.

Adidas, the German sportswear manufacturer, took more than two weeks to “review” West’s call for a “death con 3 on Jewish people” before cutting its lucrative ties with him.

The day after their star point guard promoted an antisemitic book and film on social media, the Brooklyn Nets could manage no better than a broad statement condemning “any form of hate speech” without naming Irving himself. Later, Nets owner Joel Tsai wrote of being “disappointed” with Irving, adding, “I want to sit down and make sure he understands this is hurtful to all of us.”

It was only days later, after a disastrous press conference in which Irving was unable to articulate a straightforward apology, that Tsai suspended him indefinitely.

Mastriano, who ran for governor of Pennsylvania, meanwhile, faced a barrage of criticism, including from some Republicans, before he disavowed the support that he’d received from Torba — a co-founder of the platform Gab, the online hub for extremist and conspiratorial content that Mastriano himself had utilized. (As revealed later by Politico, Mastriano accepted a $500 contribution from Torba just days before he disavowed him last July.)

In September, Mastriano drew charges of dog whistling antisemitism himself when he criticized his Democratic opponent, Josh Shapiro, for sending his children to a “privileged, exclusive, elite” school — a Jewish day school — suggesting to one audience that it showed Shapiro’s “disdain for people like us.”

In Arizona, former U.S. Senate candidate Masters’ claim in August to not even know Torba after the Gab founder strongly endorsed him, was revealed as a lie when the news outlet Jewish Insider published an audio file of the two chummily talking politics at length.

This week, voters thankfully rejected both nominees. But these reactions by major companies and by candidates of one of America’s two major parties are more dangerous than antisemitism itself. They mark the disappearance of the fences that used to keep out not just this scourge of bigotry but also anything even associated with it.

A breach in the fence

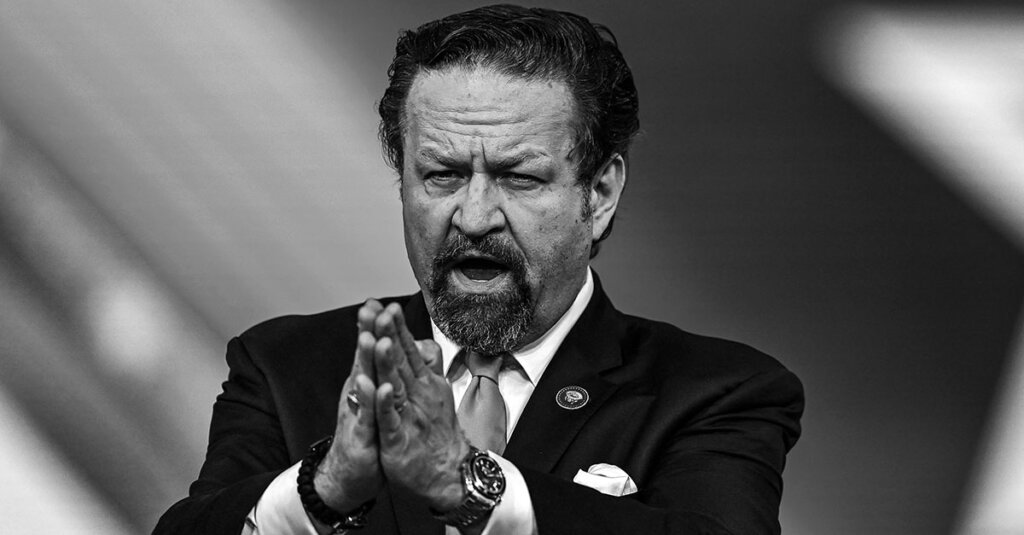

For me, the reality that the fences might no longer hold first hit home in 2017, nearly 30 years after I marveled at the Bush campaign’s quick reaction to my earlier story. That year, with a feeling of history repeating itself, I exposed the antisemitic associations of Sebastian Gorka, President Trump’s White House counterterrorism advisor.

This time, however, despite high gates and physical fortifications, the White House had no fences around it.

Gorka himself never said anything antisemitic that I, or my journalistic partner, Lili Bayer, could find. This was a point I tried to stress at the time.

But few seemed to catch the nuance: What Gorka represented — metaphorically — was the breach of the fence around the White House that had stood from the rise of Hitler in 1933 until the Trump administration.

Until Trump, no one could get anywhere near a U.S. president’s ear if they had sworn allegiance to an organization classified as a Nazi-allied group, written regularly for an infamous anti-Semitic newspaper, launched a political party with the former head of a neo-Nazi organization, or voiced support for a racist vigilante militia organized by that same organization.

That Gorka — an immigrant who came to America from Hungary — had never himself uttered an antisemitic word would have been deemed laughably irrelevant in any previous administration. A healthy concern about guilt by association — in a positive guise here — forced anyone with political, social or business ambitions to ensure that their affiliations remained above reproach when it came to antisemitism.

Set aside for a moment the endless debates about remarks by Donald Trump that play on classic antisemitic tropes, such as dual loyalty. No less important is the fence he dismantled that prevented anyone around the president — never mind the president himself — from saying anything that smacked of anti-Jewish prejudice; or from even from affiliating with entities that did so.

In the end, Gorka was dismissed from his post in August 2017. But antisemitism wasn’t the reason, according to insider accounts at the time; rather, it was Gorka’s sheer incompetence.

Today, I see Gorka as the pioneer who first breached the fence through which so many others have now followed. But it’s business leaders and other politicians who pose the real problem. They have taken their cue from Trump by lowering or even dismantling that fence themselves. Antisemitism, unfortunately, will always be with us. It’s reconstructing those fences that will pose the real challenge in the years ahead.

Correction: The original version of this article misstated the position for which Doug Mastriano ran. He ran for governor in Pennsylvania, not the U.S. Senate.

To contact the author, email [email protected].