It’s a new year. Can we please talk about antisemitism in a new way?

Antisemitism and hate crime reports don’t reflect American Jewish reality

Rapper Kanye West hugs U.S. President Donald Trump during a meeting in the Oval office of the White House, Oct. 11, 2018. (Oliver Contreras – Pool/Getty Images) Photo by Getty Images

After I wrote a column questioning whether Jews were overreacting to Dave Chappelle’s SNL monologue that featured “a lot of things that upset a lot of Jews,” I received an email from a reader who accused me of minimizing antisemitism in America.

“Our small temple in Chico, Calif., just had Nazi symbols written all over our sign,” she added. “Thankfully the police have been quite involved, finally arresting the offender through various means. The entire religious affiliated organizations and churches have been supportive and helpful — along w/ attending a Friday night service after the incident.”

It’s terrible that someone vandalized a synagogue with a swastika. But reading the email, here’s what struck me: The perpetrator was caught and punished, and local police, churches and community leaders all came to the support of the Jewish community.

The graffiti attack will likely be tallied as an anti-Jewish incident in FBI and ADL hate crime reports. But what won’t show up anywhere, except in an email to me, is the wider communal response, which was in fact anti-antisemitic.

If my community were vandalized, I doubt I’d be able to see straight, either. But by focusing on the negative, my emailer all but erased the efforts of those who demonstrated support and solidarity.

She is not alone: The American Jewish community relentlessly focuses on dire statistics, often ignoring the decades of work done to improve legal protections and to change attitudes toward Jews.

Tracking antisemitism and hate crimes is vital work. But to arrive at a true measure of our security, we must also understand and quantify the things that make us safe as Jews.

Better ways to measure hate

There is a way to measure the hate that threatens American Jews — antisemitic acts, discrimination and hate speech — as well as the things that make us secure and enable us to thrive.

Last summer, social scientists in Europe and England released a study that went all but unnoticed on this side of the Atlantic.

“Europe and Jews, a country index of respect and tolerance towards Jews” used polling data and policy information to create a single quality-of-life index for Jews in the 12 European Union countries with sizable Jewish communities.

It took into account, among other measures, actions designed to fight against antisemitism, how freely Jews could practice their faith, how deeply Jewish culture is nurtured and expressed, and how the country votes regarding Israel at the United Nations.

“They treated antisemitism as just one indicator,” said Daniel Staetsky, a statistician with the London-based Institute for Jewish Policy Research, who wrote the report for the European Jewish Association in Brussels. “And then they considered others based on all sorts of things that are important for Jews. Those are the real questions that need to be asked.”

While some of the metrics they used are debatable, using such a model here could inform a completely different approach to antisemitism than the one American Jewry has been locked into for the past several years.

Staetsky confirmed my sense that expanding the inquiry into Jewish security beyond antisemitism statistics created a much more nuanced understanding of Jewish security.

For instance, in Hungary, where antisemitic attitudes score very high, Jews have far greater freedom to practice Jewish rituals than some Western European countries, like Denmark, where a circumcision ban is imminent.

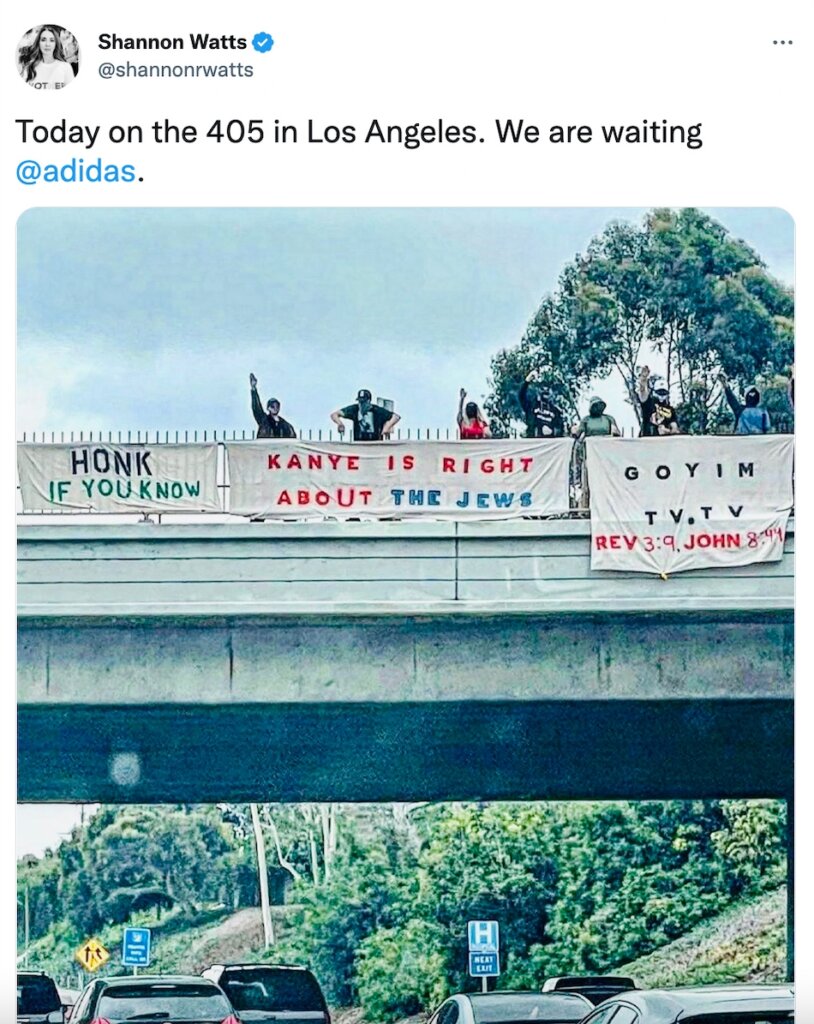

How would America rank? Who knows? We count the number of times famous people — rappers, ball players, former presidents — say or do something hateful toward Jews. We tally up the numbers of flyers some fringe group will stick under windshield wipers. We track online trolls, and of course we total actual physical attacks, as we should.

But in doing that, we often ignore many of these indicators of Jewish security: government policies on hate and tolerance, public attitudes toward Jews, legal protections against discrimination, the status of Holocaust education, policies toward Israel, freedom of worship, among other measures.

Combining these and other metrics into a single index of American Jewish security would give us a far different and, I’d venture to say, more accurate view of American Jewish life. It would enable us to fine-tune our communal programs and fundraising pitches to focus on what’s right rather than promote, as so many Jewish leaders and organizations do, a vague sense of impending doom.

‘The best-kept secret’ in antisemitism tracking

A big problem with the current way we measure Jewish security is that antisemitism statistics themselves are suspect.

The official FBI hate crime tallies are beset with problems: Local law enforcement often misreports or underreports incidents, if they report at all, and victims themselves are often loath to seek help.

“As far as trying to get a real handle on exactly how many hate crimes are happening out there, and exactly who the victims are, I don’t find that reliable in that regard at all,” Phyllis Gerstenfeld, chair of the criminal justice department at California State University, Stanislaus, told the Forward this year.

And it’s unclear what hate crime trends even mean.

“The trends in antisemitic victimization go up,” said Staetsky, “because the reporting is about 10 times better than before. That’s what we know. If there is a best-kept secret in the study of antisemitism, I told you now.”

The trends also go up, Staetsky pointed out, because online antisemitism didn’t exist when the ADL and others started their annual surveys.

These numbers are also devoid of context.

Consider the most recent Los Angeles County Hate Crime report, which sparked a wave of concern and coverage. It showed antisemitic hate crimes increased by four, from 76 to 81.

Is that a lot or a little in a county of 12 million people and 600,000 Jews? And what of the reaction to those crimes?

That same year, the city’s Jewish mayor created a citywide, interethnic task force to combat antisemitism. The state’s governor called for more funding to combat hate, along with the $150 million the legislature already granted to Jewish communal initiatives. And the LA City Council adopted the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance’s formal, if controversial, definition of antisemitism. A proper Jewish Security Index would take all these data points into account.

And what about antisemitic attitudes? A 2020 ADL poll showed that 11% of Americans harbor them. Is that a lot or a little?

“Everybody reads that and starts to worry,” said David Lehrer, the former Western region director of the ADL. “But 11% of Americans think Elvis is still alive.”

Staetsky said the numbers in Europe reflecting generally positive feelings toward Jews are steady year over year. In America, they are even better: A 2017 Pew survey found Americans felt warmer toward Jews than toward any other religious group.

That’s not to say antisemitic acts haven’t recently increased, or that we shouldn’t worry. But placing antisemitic acts and attitudes into the larger context of Jewish security and rating it on an easy-to-understand scale would help us better understand exactly how anxious to be.

Antisemitism up, Kanye down

Take social media. From one perspective, it is nothing but a cesspool of hate, a place where every antisemite can find a Jew to troll. Most measures of antisemitism only look at the nasty parts of Twitter, Facebook and other sites and apps.

But a fair assessment of Jewish security would also measure to what extent the internet and social media are places where the Jewish perspective and Jewish voices have flourished, and where our allies can speak out on our behalf.

The data points are, to say the least, mixed. On Dec. 1, Kanye West, following years of antisemitic comments, appeared on the Alex Jones podcast and declared that all Jews are pedophiles. That same day, Rabbi Donniel Hartman led a Torah study in the White House.

A week after Amazon’s Jewish CEO announced it would continue to sell the hateful, antisemitic video touted by Kyrie Irving on its site, the Jewish husband of the vice president of the United States, second gentlemen Doug Emhoff, hosted a summit on antisemitism at the White House.

But it is the antisemites, like the man biting the dog, who get the headlines and suck up more of our attention.

Google “Kanye and antisemitism” and you get 49 million results. In response to Kanye’s ravings, the rocker John Mellencamp said in a Nov. 5 speech, “I cannot tell you how f—ing important it is to speak out if you’re an artist against antisemitism.”

I googled “Mellencamp and Jews” and got 187,000 results.

The fact is, when antisemitism reared its ugly head this past month, American society clubbed it. Ye was mocked on late night, chastised by pundits across the ideological spectrum and abandoned by his sponsors.

According to the trackers, antisemitism went up. But also: Ye went down.

A call for balance

I’ve hesitated to write this column for months. No Jew in the history of Judaism ever looked smart by saying things aren’t as bad as you think. The smart bet is to assume the worst and be pleasantly surprised if you survive long enough to be proved wrong. If terrible things you expect haven’t come to pass, there’s always next year. Jews built a thriving culture in Poland for 800 years — there’s a reason so many of our families were there when the Germans showed up. But whoever predicted that community’s violent demise eventually could say I told you so. Same with Morocco, Iraq, Iran, pick your country — things were pretty good until they weren’t.

Here in America, as 2023 approaches, it’s easy to succumb to ancient fears stoked by the appearance of ancient hatreds.

“Every Jewish person I know was raised learning about all the ways people hated us and all the times we had to escape,” tweeted the writer Sophie Vershbow. “It’s an anxiety that always lives within us and due to recent events it’s been brought to the surface instead of lingering in the background.”

But that’s an argument for nuance, for data that reveals a deeper understanding of where we stand before we decide to flee.

This isn’t a call to look on the bright side. It’s a proposal to look at all sides. I’m a supporter of ADL, but the Jewish community needs an objective measure that is divorced from organizations devoted to battling antisemitism.

A Jewish Security Index, I’d argue, would actually make us safer. Focusing solely on antisemitism statistics breeds fear, stress and insecurity — never the best emotions on which to base policy, or to inspire the next generation.

“The analysis of anti-Semitism must take place somewhere between indifference and hysteria,” wrote Leon Wieseltier.

It’s time for an annual survey that hews to that middle path.