The most antisemitic university president you’ve never heard of

Johns Hopkins University must remove Isaiah Bowman from a place of honor

Exterior, Gilman Hall, looking west, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland, 1922. Photo by JHU Sheridan Libraries/Gado/Getty Images

Since George Floyd was murdered in 2020, nine major universities — including Caltech, Princeton, and Stanford — have stripped honors from their presidents who held office during the 20th century. The reason was their abhorrent racial beliefs, including eugenic racism, a pseudoscience that seeks to justify white supremacy.

But to this day, amid spiking antisemitism after Hamas’ devastating Oct. 7 attack and Israel’s ensuing war, universities continue to honor leaders who held deeply bigoted views of Jews. Among the worst of those offenders is Johns Hopkins University.

Isaiah Bowman, the university’s president from 1935 to 1948, is commemorated on campus both by a memorial bust and a nearby road that bears his name. Bowman, a eugenic racist, also was a fierce antisemite who placed quotas on Jewish faculty and students while actively working to thwart Jews’ attempts to flee the horror inflicted by the Nazis.

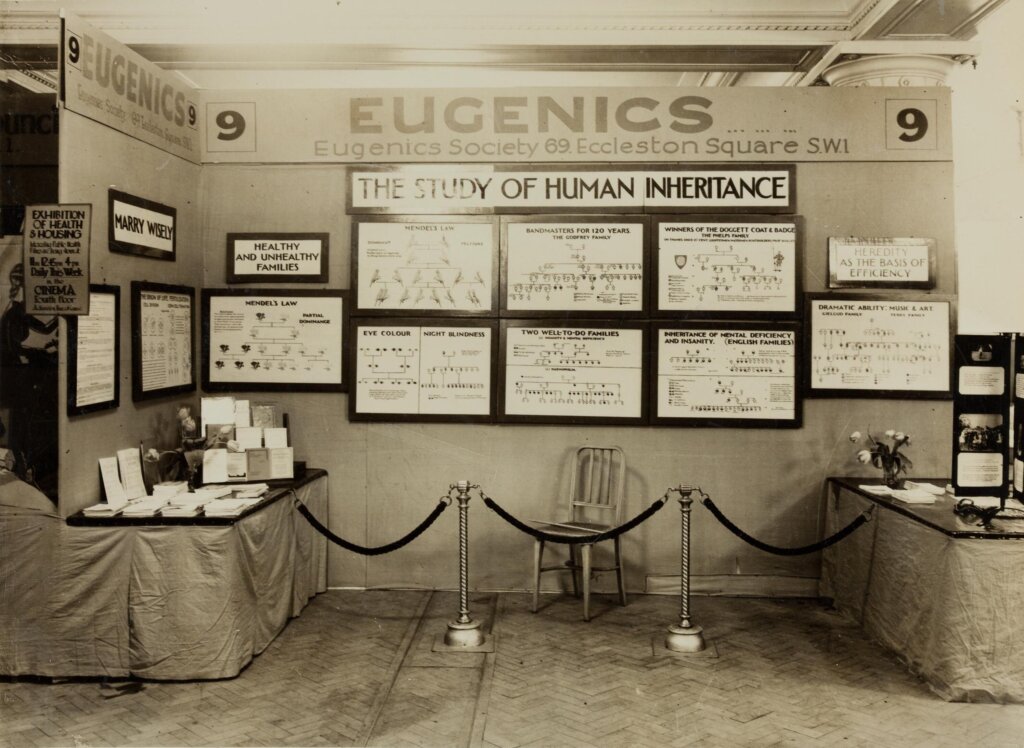

The belief system behind eugenic racism posited a hierarchy of races based on genetic inheritance. At the summit, eugenic racists believed, were northwestern Europeans designated as Aryans or Nordics. They were described as intelligent, attractive, ethical and hard-working. Those below, including Jews, had fewer desirable traits. Africans, including African Americans, were at the bottom.

To prevent the demographic replacement of superiors by inferiors — a fear echoed in today’s replacement theory — eugenic racists opposed interracial marriage, favored forced sterilization, and sought to reduce immigration from Asia and southern and eastern Europe. Bowman believed that stringent immigration quotas would exclude those whose “intellectual dispositions dilute and weaken our national character.”

Bowman grew up on a Michigan farm, studied at Harvard and Yale, and began his career with a stint teaching geography at Yale. This was followed by 20 years as president of the American Geographical Society, during which he served as President Woodrow Wilson’s chief cartographer at the 1919 Paris Peace Conference. The achievement was tainted by his opposition to Jewish efforts at the conference to obtain civil rights in Poland, Romania, and elsewhere.

Eugenic racism was in the air — at Harvard and Yale, and among members of the AGS, some of whom were its most radical exponents. One such member was Madison Grant, a white supremacist and notorious antisemite, whom Bowman appointed six times to serve on the AGS board.

Bowman brought his racial biases to Johns Hopkins when he became president in 1935.

Historians Robert Kargon and Elizabeth Hodes report that Frank B. Jewett, head of Bell Labs and an admirer of Bowman’s, was instrumental in the trustees’ choice of Bowman. Jewett was a well-known antisemite who refused to employ Jews at the labs, a policy that did not change until he stepped down in 1940.

Unlike its peers, the university placed no cap on the number of Jewish students it admitted in the 1920s. But during the Second World War, Bowman instituted a clandestine quota set at 10%, about half the percentage of Jewish students when he arrived. He did this as several other elite universities were moving in the opposite direction. By 1952, 25% of Harvard’s students were Jewish, whereas Hopkins still had the Bowman quota, although it would soon be phased out. Black students fared worse; Bowman refused to admit them.

Bowman’s contempt for Jewish students ran deep. “Jews don’t come to Hopkins to make the world better or anything like that,” he said. “They come for two things: to make money and to marry non-Jewish women.”

Bowman repeatedly blocked the hiring and retention of Jewish professors. Three years after the history department appointed Eric F. Goldman, a brilliant young scholar, Goldman’s contract was not renewed because Bowman felt “there are already too many Jews at Hopkins.” Bowman imposed a cap of one Jew per department but the School of Medicine was autonomous.

James Franck — physicist, Nobelist, and German Jewish emigre — left Johns Hopkins for the University of Chicago after four years because, he said, Bowman “made life very difficult for Jewish faculty.” Franck was astonished when Bowman suggested he moved to Chicago for the pay, the old slur that Jews care only about money.

It’s true that Bowman openly criticized the Nazis for their territorial ambitions. It’s also true that he never said a word publicly to condemn their treatment of Jews.

That’s just as well. On a visit to Germany in August 1938, he wrote a letter reporting on conversations he was having with Germans about what he called “the Jewish business.” According to Bowman, Germans grumbled that during the Weimar years, Jews gained undeserved opportunities. He heard Germans argue that Jews had appeared in places they’d never been before and behaved arrogantly. Bowman admitted that some of the complaints may have echoed Nazi propaganda, but also, tellingly, added that “they may be right in spots.”

There’s disagreement about the adequacy of President Franklin Roosevelt’s response to the crisis in Europe. Sympathizers say that his humanitarian instinct to admit more refugees was constrained by opposition from voters and congressional isolationists. Critics argue that he was cautious to a fault and sought to offload the burden on other nations, as at the failed Évian conference he convened in July 1938.

That November came Kristallnacht, at which time Roosevelt suggested that refugees might be resettled in Latin America. He asked Bowman, an expert on Latin America whom the president had known since 1921, to be his “special adviser” on refugees.

Bowman’s advice and his behavior at Hopkins were of a piece: keep Jews away. He struck down every Latin American location Roosevelt suggested for resettling Jews fleeing Hitler, citing an inhospitable climate and other problems. It’s possible that Latin America’s proximity to the United States caused Bowman to fear a subsequent influx of Jews to this country. Immigrants from Central and South America were exempt from the quotas established in the 1924 immigration law.

Bowman also recommended curbing Jewish immigration to Australia out of fear that Jews might become too powerful a force there: “The danger lies in Jewish control of the economic organization if too many are allowed into the country,” he wrote in 1942. Here was another antisemitic staple, which the Nazis at that very time were using to perpetrate a genocide.

Bowman’s reluctance to open pathways to help rescue European Jews operated at a personal level, too. In spring 1941, Alfred Philippson, the only Jewish geographer in Germany to hold the highest academic rank, was under house arrest with his family. A rescue campaign commenced, led by Philippson’s colleagues. Bowman’s 20 years at the AGS made him well known among geographers. Several appealed to him to hire Philippson to give lectures at Hopkins or help raise funds to bring him to safety in Switzerland. That fall, Bowman was told that the situation was dire, yet he made no promise to do anything.

Come March 1942, Bowman still had not acted. The following month, the Nazis sent the Philippsons to Theresienstadt. Fortunately, they survived. Philippson’s biographer believes that, “because Bowman was such a well-known and respected professor, who had a lot of power and influence, he himself could have reacted differently and could have been an ideal to others.”

During the war, Bowman oversaw a secret White House project on refugee resettlement but never produced a single rescue plan. Instead, he turned the project into an academic exercise, ignoring practical solutions and stalling action. He also advised the State Department on postwar policies, including settlement of survivors, whom he wanted to remain in Europe, and on planning for the United Nations, another accomplishment besmirched by his prejudices against civil rights for African Americans, Jews and colonial peoples.

Bowman’s stalling, and that of his colleagues in the State Department, disturbed several of Roosevelt’s top advisers, notably Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau Jr. He complained to Roosevelt that the State Department was sabotaging rescue efforts. In response, Roosevelt created the War Refugee Board in January 1944; it rescued perhaps as many as 200,000 Jews and 20,000 non-Jews during its brief existence.

President Harry Truman fired Bowman shortly after the war and pulled back the curtain on the State Department, singling out “an antisemitic bunch over there.” Historian James Loeffler called Bowman the State Department’s “worst antisemite.”

Bowman’s death in 1950 coincided with the opening of an era in which American Jews began to feel included and safe. Perhaps it’s why the honors bestowed on him were accepted for so long. (The bust was erected in 1954.) But the return of antisemitism — including on university campuses — is eroding that sense of security.

As antisemitic incidents have escalated, universities have responded with practical guides for reducing campus antisemitism. They’ve launched educational programs and research centers.

What’s missing is a commitment by universities to delve deeper into their own antisemitic pasts, to show that they are committed to not reliving the egregious episodes that characterized too much of 20th-century higher education. The effort cannot only be an academic exercise; action is necessary too.

Last September, we asked the Name Review Board at Johns Hopkins to remove Bowman’s bust and rename the road. Fifty distinguished scholars — historians, geographers, and others — have endorsed the effort. The ongoing decision process is complex; the university’s president will make the final decision.

Some view denamings and renamings as an affront to history. But there’s a distinction between history and monumentalization, as Caltech’s current president pointed out when Caltech withdrew honors from its founding president, Robert A. Millikan, a Nobel prize winner and eugenic racist. Venerating people like Bowman can no longer be tolerated, neither at universities nor elsewhere.