India’s Jewish ‘Lost Tribe’ Faces Hard Times in Israel

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

TEL AVIV — According to ethnographers and Israeli geneticists who have investigated the matter — and even most members of his own ethnic group in India — Hanoch Haokip’s claim to be descended from one of Israel’s so-called “Lost Tribes” is, at best, highly debatable.

But Haokip, a member of a small subgroup of indigenous peoples from a remote tribal area of East India, has no doubt about the matter. During an interview in the northern Israeli town of Akko, where he lives today, Haokip, whose group is known as the Bnei Menashe, spoke with some indignation about having been “interrogated” by the rabbinate during his formal conversion — or as he sees it, return — to Judaism.

“Of course, you understand that the rabbinate, the government, needs to do these things,” interrupted Zeev Wagner, a member of an Orthodox social welfare group associated with Shavei Israel, the organization that has brought Haokip and several thousand other members of his group to Israel over the last 20 years, as soon as Haokip voiced this feeling.

During an interview with the Forward, Wagner sat next to Haokip, carefully monitoring what he said. But later, when he was alone, Haokip spoke worriedly about the influence of Israeli secular society on his preteen girls, who sat in a seeming daze, watching YouTube videos of American girl bands as their father sat sipping tea at his living room table. It was a culture, he said, that encouraged their “complaining.” Moreover, he added, his children sometimes face racism at school, and are at times mockingly labeled “Chinese.”

Still, Haokip stressed his strong identification with Zionism and the pride he feels that his community of immigrants, which lives mostly in northern Israel and in the Israeli-occupied West Bank, is “getting stronger by fighting against the Arabs, to show that this is a land that belongs to Jews.”

As he explained it: “Some people think that we have come here to be Israeli. No, we are not interested in that. We have come here to be Jews.”

Haokip, who works as a community liaison for Shavei Israel, embodies many of the paradoxes that currently characterize the rough process of immigration and absorption for this tribe who, indeed, often seem lost in the maze of Israel’s complex bureaucracy and hurly-burly culture. Reinforced and encouraged in their convictions that they are descended from ancient Jewish roots by Shavei Israel, a group funded in part by evangelical Christians, some 3,000 Bnei Menashe have relocated to Israel with support from the organization. Most arrived without state recognition as Jews, and the benefits in aid and support this brings. Most converted only after they moved to Israel with help from Shavei Israel, which is devoted to searching the earth for groups that it believes share Jewish lineage.

The Jewish Agency, which traditionally organizes the immigration process for Jews in the Diaspora, collaborated with Shavei Israel in the Bnei Menashe’s case. In Israel, the Ministry of Absorption similarly ceded much of its role to Shavei Israel, which was able to secure almost $2 million in public funding without going through the usual government bidding process.

This has left Shavei Israel — a group some accuse of exploiting the Bnei Menashe for ideological ends by settling many of them in exclusively Jewish West Bank settlements that the international community regards as illegal — as the group’s main source of support and assistance in Israel.

The result so far has been a group plagued by absorption and integration difficulties as harrowing as those faced by many previous non-European immigrant groups in Israel — and maybe more so, thanks to their sheer distance from Jewish life until recently, and to the skepticism that still surrounds their claims of a past Jewish connection.

According to Malachi Levinger, the head of the local council of Kiryat Arba, a city in the West Bank where 700 Bnei Menashe have settled, including many placed there by Shavei Israel, at least 73% of the group’s youth are considered at risk.

With their parents mostly absent because of their need to work long hours at low-end jobs, teenagers from the community are prone to alcohol abuse, petty crimes and encounters with the police, said Yoni Nachum, coordinator of Bnei Menashe programs for the local council. According to Nachum, the Bnei Menashe, like earlier communities from Ethiopia or Morocco, have seen their traditional family structure and support network upended by their move to Israel.

“What is different here is that they have been neglected for some 20 years, and we are only now starting to see the implications,” Nachum said.

Despite the doubts and problems, the Bnei Menashe community in Israel continues to grow gradually, with some 700 new members expected to arrive to the country in the coming year, up from the 260 immigrants last year.

Haokip believes some 90% of Bnei Menashe youth have “lost their way.”

“It’s very hard for them, at that age, to know which culture to follow,” he said, “the one where you respect your elders, or where you are fully independent.”

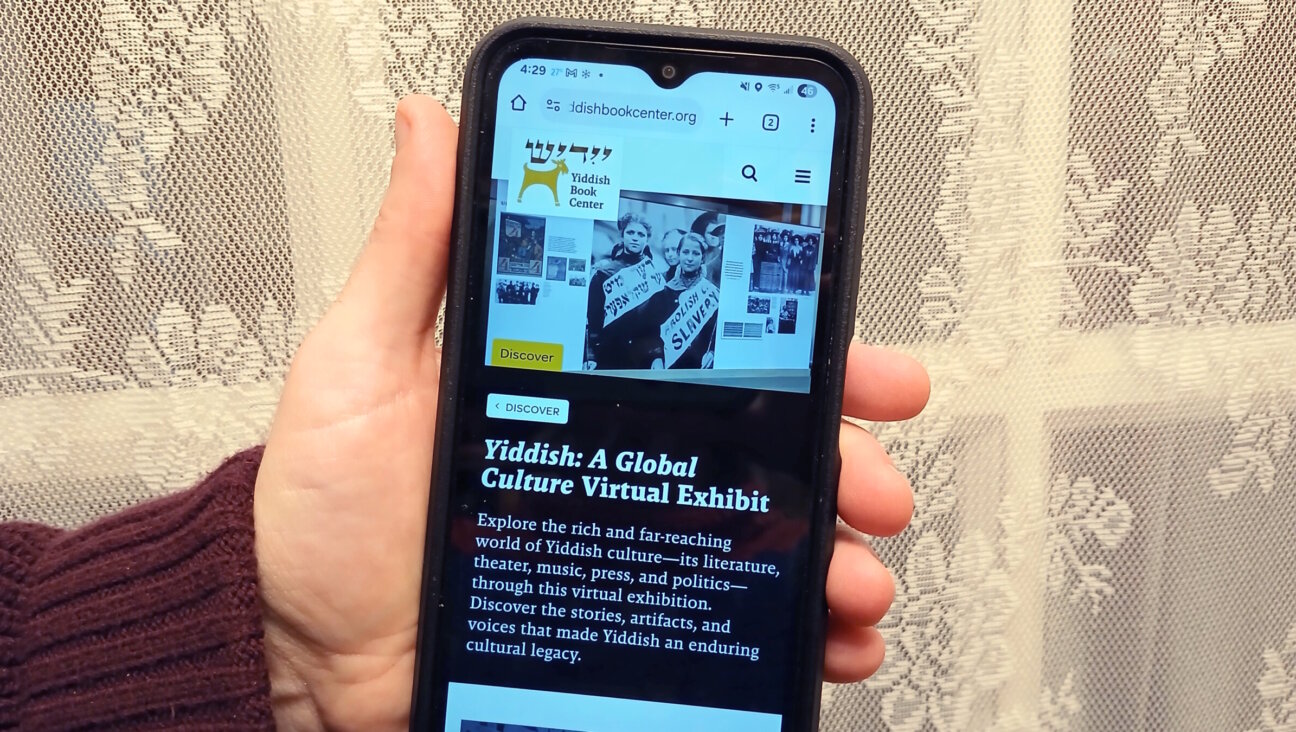

Modern Family: Hanoch Haokip, talks on his cell phone at home in Akko while his daughters immerse themselves in screens.

The Bnei Menashe identify as descendants of “Menasseh,” one of the sons of Joseph, the biblical patriarch. According to their understanding of their tradition and oral accounts of their origins, they claim to have been living in exile since expulsion from Israel by the Assyrians at the end of the First Temple period more than 2,700 years ago.

The ethnic groups from which the Bnei Menashe come are the Mizo, Kuki and Chin peoples, a conglomerate of different tribes speaking various dialects of Tibeto-Burman languages. The community settled 400 years ago in India’s remote northeastern states of Manipur and Mizoram. There, as Shalva Weil, a Hebrew University of Jerusalem anthropologist who has studied the group, explained, some members from these tribes, who were originally animists, “were converted twice.”

The first time was in the 19th century, when Western missionaries converted many members of these local groups to Protestant forms of Christianity. Reading the Bible, some of these new Christians saw in its descriptions of the ancient Israelites echoes of their own traditional practices. Among other things, the group practiced animal sacrifice during Passover and retold an oral tradition that chronicled its journey through Persia, Afghanistan, Tibet, China, and onto northeastern India.

Only relatively small numbers of the Mizo, Kuki and Chin identified with this new understanding of themselves. An estimated 10,000 out of an estimated 2 million of their fellow tribesman do so today. But in 1983, an Orthodox rabbi from Jerusalem, Eliyahu Avichail, encountered these groups of Christians who saw their roots in the Jewish Bible. Avichail’s life was devoted to a search for traces of the Ten Lost Tribes of Israel, which Jewish tradition depicts as having vanished from history in the Babylonian Exile of the sixth century BCE. It was he who gave these groups the name “Bnei Menashe” and encouraged their “return” to Judaism, which included their abandonment of belief in Jesus. But notwithstanding the Orthodox Jewish practices he taught them, most had no way to formally convert in their remote corner of the world.

Through Avichail, the Bnei Menashe began to learn about the mitzvah of moving to Israel. Small numbers were able to do so with financial backing from the International Fellowship of Christians and Jews, a group that was founded by Yechiel Eckstein, an Orthodox rabbi, and is composed overwhelmingly of evangelical Christians. Its members seek to support Israel, for many, in part out of their belief that the ingathering of Jews worldwide in the Holy Land is a prerequisite for the return of their Messiah, Jesus Christ.

In the early 2000s, the immigration of the Bnei Menashe reached a new scale. Michael Freund, an American-born former aide to Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, included them in the wide-ranging plan of his group, Shavei Israel, to bring tens of thousands of “lost Jews” from remote corners of the world.

The group, which was well-funded, received some of its backing from Christian evangelical groups, including Bridges for Peace and the International Christian Embassy in Jerusalem. In lobbying Israel’s government for support, Freund’s organization cited a 2005 ruling by the Sephardic chief rabbi, Shlomo Amar, that declared the group to be “seed of Israel” — a halachic term to describe individuals not considered Jewish according to religious law, but whose proven Jewish ancestry makes possible their immigration to Israel.

But a February 2015 investigative article by Haaretz reporter, Judy Maltz cited a contradictory Interior Ministry document. This document states that Amar ruled that the Bnei Menashe are not “seed of Israel,” according to the accepted halachic definition of the term, and have no proven Jewish ancestry. Amar confirmed to Haaretz that this was indeed his ruling.

In 2005, the year of Amar’s alleged ruling, the government of Prime Minister Ariel Sharon, did not in any event support the mass immigration of the Bnei Menashe. But in 2009, when Freund’s former boss, Netanyahu, returned to the prime minister’s office, immigration of the Bnei Menashe to Israel resumed after a five-year hiatus, and on a much larger scale than before.

In pushing for the immigration of groups with uncertain Jewish connections to Israel, Freund has cited ideological reasons grounded in demography.

Found Tribe: Michael Freund in India with a member of the Bnei Menashe. Image by Shavei Israel

“As the percentage of Jews continues to decline, it will grow increasingly difficult for Israel, as a democracy, to ignore mounting calls by its Arab minority for cultural autonomy and perhaps even self-rule,” Freund wrote in a September 2001 Jerusalem Post column. “And if the day were to come when Arab Israelis could elect more representatives to the Knesset than Jewish Israelis, the Jewish identity of the State would be in grave doubt.

“For a country struggling to find potential new sources of immigration,” Freund explained, “groups such as the Bnei Menashe and others like them might very well provide the answer.”

Notwithstanding the strong Orthodox Jewish religious practices that Shavei Israel has succeeded in inculcating among many of the Bnei Menashe, Weil, the Hebrew University anthropologist, wrote in a 2004 study that “there is no documentary evidence of Jews or Israelites on the Indo-Burmese borderlands, and legends about the Ten Lost Tribes were not traditionally associated with this culture area.”

In 2003, patrilineal DNA testing of 350 genetic samples from the Bnei Menashe community at the Technion-Israel Institute of Technology in Haifa found no evidence to indicate a Middle East origin for the group. The study was conducted by the geneticist Karl Skorecki, a co-discoverer of the so-called Kohane priestly gene. In 2004 an Indian study of matrilineal DNA conducted at Kolkata’s Central Forensic Science Laboratory found evidence that some female members of the tribe apparently shared some DNA with Middle Eastern peoples, most likely through intermarriage.

Skorecki criticized the Kolkata study for failing to conduct a complete sequencing of the DNA, but cautioned that even after complete sequencing, “It is possible that after thousands of years it is difficult to identify the traces of the common genetic origin.”

It is just a trailer overlooking a horse farm and the rolling hills of the West Bank, but Reuven Goita — a teenage member of the Bnei Menashe community — recalls with gratitude today how social workers at Beit Miriam, an after-school center, rescued him from a bleak future. Speaking by phone from his yeshiva in Jerusalem, Goita said that it was there that he “was born again as an Israeli.”

As his parents worked late-night shifts in low-wage jobs, Goita spent much of his childhood at the Beit Miriam trailer in Kiryat Arba, a religiously conservative and politically hard line West Bank Jewish settlement. There, he and some 60 other Bnei Menashe children were given homework help, taught Israeli songs and culture, and served dinner by their Israeli “adopted mothers.”

“Since arriving at the age of 8, I’ve learned to connect with the land, to have the confidence to fulfill and defend the promises of Zionism,” said Goita. “This is something that we were always yearning for back home in India.” Today, at 17, he sports a thin mustache, a white yarmulke and a pressed shirt in the fashion of the territory’s many yeshiva boys.

Once a year, Beit Miriam celebrates Bnei Menashe heritage during a “Roots Night,” but Goita said that his identity now springs from his new hometown in the Judean Hills — an exclusively Jewish settlement near the Palestinian West Bank city of Hebron that has been a flashpoint during the past eight months of Israeli-Palestinian violence. Goita said that his childhood in the West Bank has motivated him to enlist in a military combat unit that he will enter upon graduating from yeshiva.

As the Bnei Menashe celebrate their return to “Zion,” they count teenagers like Goita among their rare success stories.

But for most, while parents often work hard in cleaning or security jobs, “children are hanging out in the streets, smoking, stealing, drinking,” said Hedva Hadida, director of the Beit Miriam afterschool program.

With aggressive lobbying by Shavei Israel, the government has this year committed to spending $2 million on integrating the Bnei Menashe. Since most do not come to Israel as recognized Jews, they are not eligible for many standard forms of aid available to Jews who immigrate under the country’s Law of Return. But Immigrant Absorption Minister Zeev Elkin has said that Israel will also create a government assistance program for the community for up to 15 years. It’s not clear how much money this will mean. But Freund says that the country has come a long way towards fulfilling its “responsibility” toward these “lost Jews.”

Many say that it is the community’s polite and reserved culture that prevents them from getting more support from Israeli authorities. “We tell them all the time, this is the Middle East, if you don’t voice your specific complaints, we won’t know what to help you with,” Freund told the Forward.

Shimrit Zentusawn Ngaihte, 20, a Bnei Menashe member who came to Israel two years ago, said that the government had been “so loving.” But she was disappointed to have been placed in a menial factory job despite having passed all of her pre-med school exams in India.

Smiling profusely, sitting with her hands crossed in her lap, Ngaihte had at her disposal only a handful of Hebrew words but insisted that she was fully Israeli, which meant, she said, that she was “living the Torah way of life.” She said that her mentality was starting to change as well. She boasted of having signed a petition to the government to extend language classes for Bnei Menashe to eight months from five.

“Until now, I never tried to talk about my rights, but the light has started to turn on in my head; it’s in the process,” she said, blushing.

Contact Shira Rubin at [email protected]