The Forward JEWISH. INDEPENDENT. NONPROFIT.

Featured Articles

Fast Forward

-

Should ‘From the river to the sea’ be allowed on Facebook and Instagram? Meta’s Oversight Board is considering the question.

-

At March of the Living on Yom HaShoah, Holocaust survivors and relatives of Oct. 7 victims stress urgency of remembrance

-

’50 Completely True Things,’ a Palestinian-American’s call for compromise, strikes a chord on social media

-

Immigrants in Israel

News

News

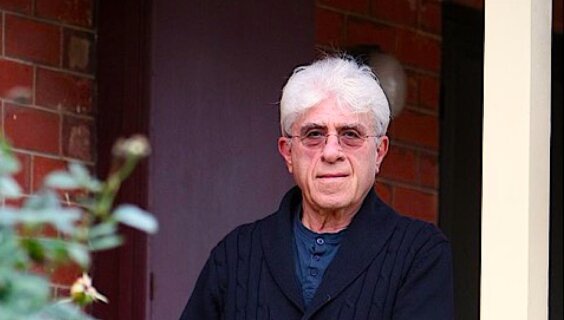

‘Jewish enough to be murdered,’ but not buried in a Jewish cemetery

The rabbis in charge do not consider some victims of Oct. 7 Jewish — even though their families do

-

Conflict on Campus

-

FORVERTS פֿאָרווערטס

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

-

Don't Miss This

Culture

Culture

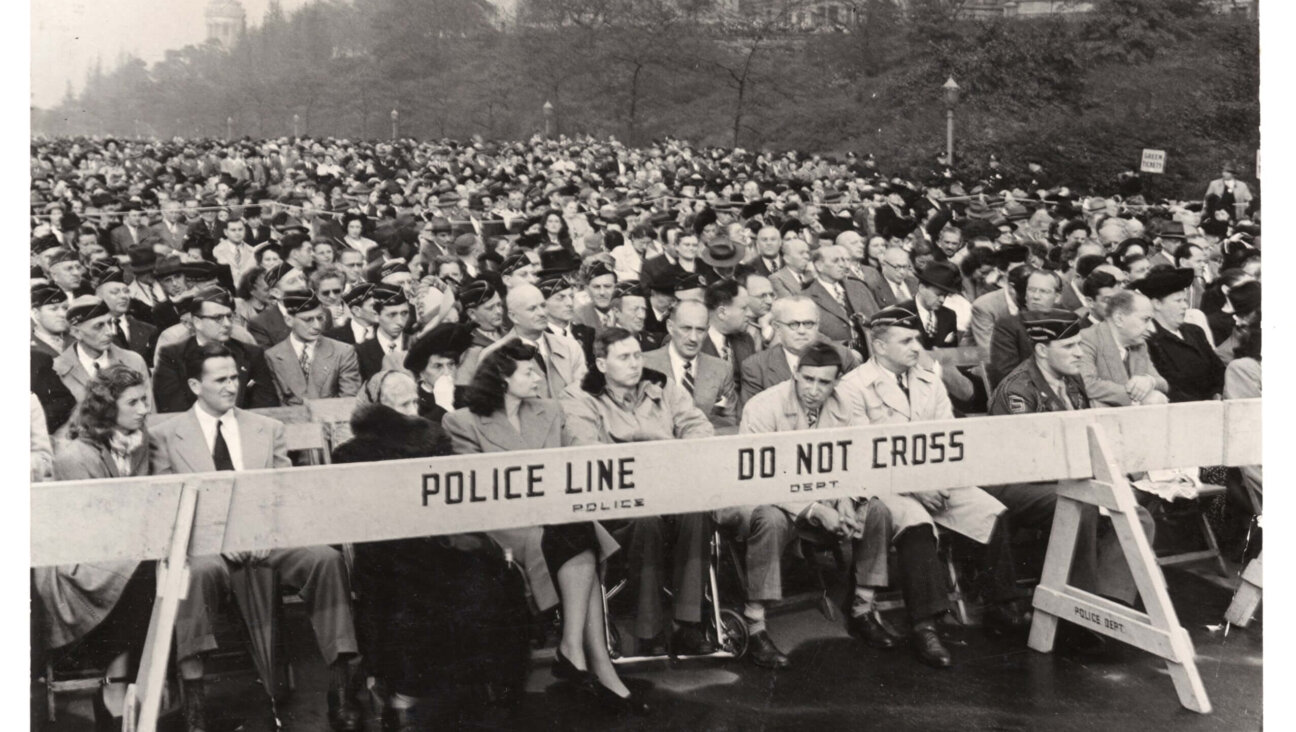

Could this be the most meaningful Holocaust memorial in New York?

In Riverside Park, a stone meant to be a placeholder for a grander memorial has become an unlikely gathering place for Bundist Holocaust survivors and their descendants

-

Forward Backward

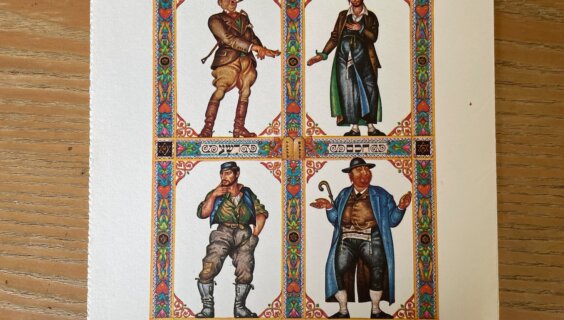

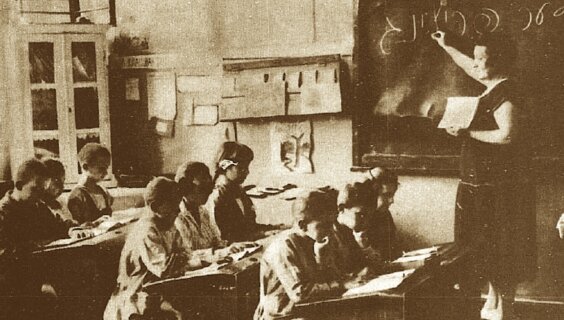

Forverts in English How the Forverts historically related to its women readers