Men explain Anne Frank to me

The idea of Anne Frank surviving has been done, frankly, to death — almost always, by men.

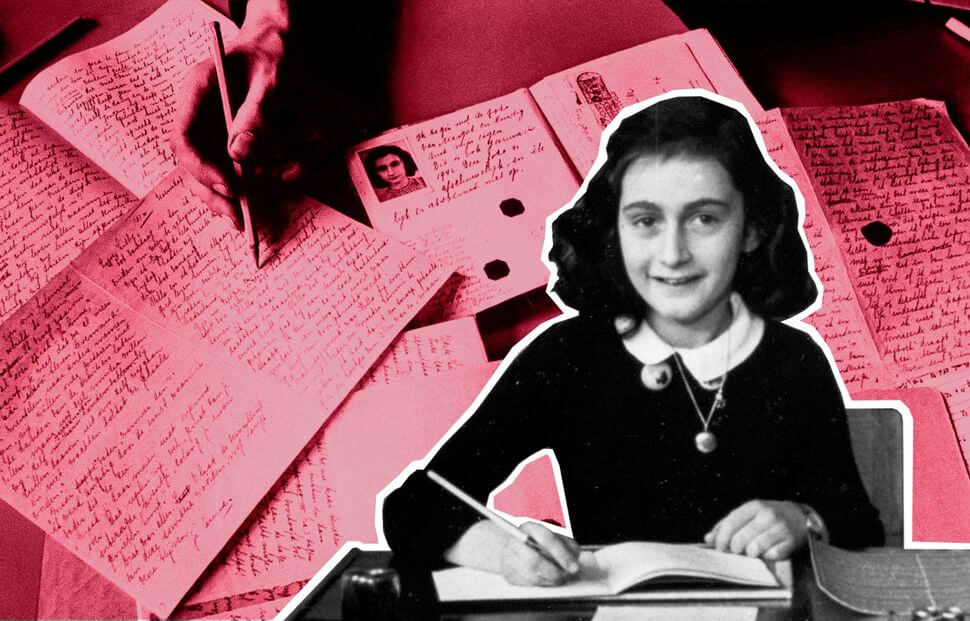

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

Anne Frank is alive.

Pick up a novel and you’ll find her hearty and well, decades after the Holocaust. She is living in the northeastern United States, an attractive young woman or a traumatized crone. She is a writer whose adult accomplishments never live up to those of her youthful diary. She is the idol of Yiddish-slinging girls from Flatbush. She says “Blow me.”

Oh, and one more thing. Wherever she winds up — the Berkshires, western New York, Manhattan — a man has put her there.

David Gillham’s forthcoming novel “Annelies,” which begins with the premise that Frank survived the concentration camps, is part of a surge in cultural interest in Frank that has corresponded with the recent global resurgence of the forces that made her life so perilous. Last October, Ari Folman and David Polonsky, the pair behind the animated documentary “Waltz With Bashir” (2008), released a graphic adaptation of Frank’s diary that they will soon follow with an animated Anne Frank film. In August, reports circulated that a Los Angeles production of the play “The Diary of Anne Frank” would cast the Nazis as Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents — a rumor that turned out not to be true. As the horror of the Trump administration’s family separation policy unfolded, activists and editorial writers noted that Frank’s family had been denied the right to immigrate to the United States. The lonely children shocking us on the news were all potential Franks.

Clearly, Frank, who would have turned 90 this year, has survived. Yet male novelists, of whom Gillham is merely the most recent, appear not to have noticed. Philip Roth revived her in “The Ghost Writer” in 1979. Shalom Auslander did the same in “Hope: A Tragedy” in 2012. And novels aren’t the only places where a living Frank shows up. Matt Siverton’s 2017 film “Love All You Have Left” found Frank in the attic of a modern-day mother grieving her daughter’s death in a school shooting, and Aaron Kreuter’s 2018 story collection “You and Me, Belonging” features a story in which a stoned young Jewish man fantasizes about Frank going on Birthright Israel. The idea of Anne Frank surviving has been done, frankly, to death. But why? And why, almost always, by men?

A woman, let alone a young one, has rarely proved to be the most lasting voice of victimhood to emerge from an atrocity.

American slavery had Frederick Douglass. World War I had T.S. Eliot, Siegfried Sassoon and Wilfred Owen. South African Apartheid had Nelson Mandela.

Frank chronicled the crimes of the Holocaust at a remove, conveying only what she heard on the radio and saw from her annex window. But her visceral, elegant writing has defined the experience of that genocide for generations: The fear. The boredom. The dissonance between meeting the demands of daily life and constantly anticipating death. The way that grief defines even the most trivial thoughts. “Sometimes I’m afraid my face is going to sag with all this sorrow and that my mouth is going to permanently droop at the corners,” she wrote.

“She wasn’t just any old writer who happened to live through a terrible moment,” Francine Prose, author of the 2009 book “Anne Frank: The Book, The Life, The Afterlife,” told me. “She could put you in the scene.”

Frank’s status as the most engaging chronicler of the Holocaust is especially significant, because the subjugation of women was nearly as much a part of Nazi ideology as belief in the dominance of the so-called Aryan race. Frank’s death in Bergen-Belsen served that ideology’s goals. But the prevailing power of her voice — that of a Jewish girl — refutes them.

Frank was acutely aware of the challenges facing Jewish girls. Her preternaturally mature understanding of anti-Semitism is well known: “We can never be just Dutch, or just English, or whatever, we will always be Jews as well” is one of her diary’s most commonly cited quotes. But her popular image has rarely incorporated her painful reflections on womanhood, a central concern of her diary during her final months in the annex.

“Of the many questions that have often bothered me is why women have been, and still are, thought to be so inferior to men,” she wrote on June 13, 1944, two months before the Nazis would invade the secret annex. “It’s easy to say it’s unfair, but that’s not enough for me; I’d really like to know the reason for this great injustice!”

Image by Ulf Andersen/Getty Images

Men have, for various reasons, found this aspect of Frank’s work uncomfortable. Frank’s father, Otto Frank, who edited and published his daughter’s diary after the end of World War II, famously excised several pages of her musings on gender and sexuality, including passages in which she wrote in detail about her own genitalia. But even as many of Frank’s most intimately female musings were absent from her diary for its first half-century in the public eye, introduced in new editions only in the late 1990s, her diary was marketed as a specifically female object: “The Diary of a Young Girl.”

Women often read Frank’s diary for the first time while they’re young, before they become familiar with Frank as a symbol. “[The diary] had a huge effect on me when I was a kid,” Prose said. “I was walking around in a state of grief all the time. It was so powerful. I read it and then I read it again and I read it again and I read it again.”

Rachael McLennan, author of the 2016 book “In Different Rooms: Representations of Anne Frank in American Literature,” said, “I loved reading her diary when I was young. When I was 10 or 11 I got the diary and just found Anne Frank completely fascinating — so smart and sympathetic. I think that’s how a lot of people, especially young women, get into her stories.”

By contrast, men who have written about Frank have often been introduced to her as a symbol of the Holocaust, but didn’t read her diary until much later.

When they did, the work made an extraordinary impact. “It’s shocking how beautiful it is, how heartbreaking it is,” Auslander said, “even without the ending.”

Male authors who revive Anne Frank profess laudable motives for doing so: devotion to her writing, outrage at her misrepresentation, a fear that she’ll be forgotten, a wish to grant her story a less horrific ending.

Yet their works rob Frank of independence and authenticity. And it becomes hard to see their insistence on trying to give her a new voice — a living voice — as anything but an attempt to appropriate her power.

The novels these men have written share some common qualities. They cast a disparaging eye on Frank’s inherent abilities as a writer. They situate her in relation to men: She’s a supplicant for the attention of a male author in “The Ghost Writer,” a shrewish burden on a nebbishy family man in “Hope: A Tragedy,” a floundering girl fighting with her father and crushing on a Nazi’s son in “Anneliese.” And, notably, the novels enter into an odd sort of contest with Frank by claiming to write what she couldn’t, on her behalf.

This does not happen to most significant cultural figures, even those who die tragically and young. While conspiracy theorists may claim that Elvis is alive, singers don’t tend to channel the King by claiming to sing with his own voice. Marilyn Monroe remains a pop culture icon, but you’d be hard-pressed to find literary depictions of her at 80, overdose be damned. The idea of a novel written from Martin Luther King Jr.’s perspective in which he survives his assassination is instinctively offensive. Writers adapt one another’s work all the time, but it’s rare that they claim some measure of control over the legacy of one of their own.

Elie Wiesel, who wrote the other most monumental text of the Holocaust, “Night,” survived the concentration camps and went on to a long and distinguished career as an author. But there are, at least in English, no novels in which he is featured as a major character. The same is mostly true for Primo Levi, though the character of Louis Levy in Woody Allen’s “Crimes and Misdemeanors” is widely thought to be a thinly veiled representation of Levi, and Levi’s memoir “If This Is a Man” was adapted by Antony Sher into the play “Primo,” which made no major alterations to Levi’s own account of his life.

And Frank is not the only writer to figure as a character in “The Ghost Writer”; she appears alongside the fictional author E.I. Lonoff, who recalls both Bernard Malamud and Henry Roth. Why did Roth give those authors the courtesy of a fictional mask, and deny it to Frank?

Image by Astrid Stawiarz/Getty Images

In “The Ghost Writer,” the answer seems to be that Roth didn’t see Frank as an author. He saw her as an object that American Jews had made sacrosanct — a perfect target for his always skeptical pen. His Frank is talented, but her diary comes into existence effectively by accident, rather than through the intensive craft that Frank in fact practiced. In “The Ghost Writer,” Frank’s memories of the secret annex where she lived in hiding from the Nazis are clear. But, Roth writes, “of the fifty thousand words recording it all, she couldn’t remember writing one.” When she rereads her diary, her first thought is that it would make an impressive piece of college schoolwork: “How nice, she thought, if I could write like this for Mr. Lonoff’s English 12.”

Auslander’s novel finds Frank as the unwelcome tenant of its protagonist, Solomon Kugel, a middle-aged man made neurotic by the placid — too placid — circumstances of his life. Hidden away in Kugel’s attic, Frank is a foul-mouthed 80-something whose failure to produce her sophomore book has made her both self-obsessed and mad. “I am a writer, Mr. Kugel, do you hear me! A writer!” she screeches.

And Gillham treats Frank’s diary as a product of adolescent angst. “In her diary Anne turns herself inside out and stares into all her inner recesses,” he writes. “Splashing ink on the paper, sometimes boisterously, sometimes angrily, often critically, perhaps even artfully.” His Frank eventually settles in New York and becomes an accomplished author. But at 32, she admits that the diary will be the book that “she will be remembered for, no matter what else she might produce.” The only one of her other works to which Gillham, who is not Jewish, grants a title is “Answer the Night,” a name too close to that of Wiesel’s masterwork to be accidental.

Why is Frank so discredited by those who claim to admire her? Why do they insist on speaking for her? Part of the answer lies in the fact that she belongs to two categories of people — women and children — who historically have not been allowed to speak for themselves. “It seemed to me that people were weirdly resistant to this idea of [Frank] as a great writer,” Prose said. “They were wedded to this idea that had come more from the films and the play than the diary itself, of how spontaneous [the writing] was. I began to think that people were really reluctant to give that kind of agency to, or admit that talent in, a girl.”

It’s also hard not to wonder just what else Frank might have produced had she survived the Holocaust; the forthcoming “Anne Frank: The Collected Works,” scheduled for a June publication timed to what would be Frank’s 90th birthday, expresses that wishfulness in its very title. “Because she died so young, people can project onto her, because her future was unwritten,” McLennan said. “I think writers are attracted to imagining what that future is.”

In practice, that imagination becomes a way of saying, if indirectly, that Frank’s own accomplishments were not enough.

“Had she actually lived, I doubt I would have written this book,” Gillham said, “because it wouldn’t have been necessary.”

Anne Frank’s fictional life in America began in the pages of “The Ghost Writer.” In that novel, Roth’s alter-ego Nathan Zuckerman, 23, spends the night at E.I. Lonoff’s home, smarting over his father’s criticism that one of his short stories is unflattering to both their family and the Jewish people.

Enter Amy Belette, an enigmatic young woman whom Zuckerman fantasizes is secretly Anne Frank. Belette, who is also a guest of Lonoff’s, is a skilled writer, once a refugee, very beautiful. Zuckerman pictures her, as Frank, being devoted to Lonoff to the exclusion of almost any other interest. When Frank-Belette reads her published diary for the first time, Zuckerman imagines that she is thinking of Lonoff: “Everything she marked she was marking for him, or made the mark pretending to be him.”

There is little to suggest that Belette is actually Frank, and much to suggest that Zuckerman has invented that story to excise some angst about, well, being Jewish. “The very premise — bringing Anne Frank to life in a story about a writer — Roth told me.

The paradox Ozick was highlighting the conflict between being a good writer and being a good Jew, a guiding theme in “The Ghost Writer.” “The writer has no restraint, and ought not to have restraint,” she said. “On the other hand, the writer is also a citizen.” Zuckerman pretends that his fantasy about Frank is about Jewish redemption, but it’s really about the thrill of his own authorial prowess. Roth writes that Zuckerman has crafted “a fiction that of course would seem to [his community] a desecration even more vile than the one they had read.”

Image by Michael Zide

That same conflict between good writing and good citizenship appears central to Auslander and Gillham’s need to resurrect Frank. The good Jew — or citizen — respects Frank’s place in the culture. The good writer abhors Frank’s posthumous sainthood, challenges a culture built on the worship of her victimhood, and perhaps wants, in Auslander’s words, to “have fun with a sacred cow.”

“I had so much guilt involved in writing about her that I thought that I needed to go back and get my own idea of who she might be, rather than the angelic victim that I was taught about for so long,” Auslander said. “By the time I was 18 I [had] just kind of hated her, because she stood for my ultimate demise.”

When he finally read her diary, he was astonished. “The more I read — it was just the fire in her, a beautiful fire — the angrier I became that she had been turned into the Jewish Jesus,” he said. Gillham was similarly surprised when he first read Frank’s work in his 20s, having turned to it after reading “The Ghost Writer.” But he says he wasn’t angry — just awed, and concerned that knowledge of Frank might dwindle. “I just want Anne Frank remembered,” he said.

Each assumed that his experience was fairly universal. But it’s not.

Like Prose and McLennan, who spoke of their powerful encounters with Frank’s work when they were young girls, Ozick told me that she saw an overwhelming “identification with Anne Frank by young women.”

What Auslander and Gillham didn’t account for was the existence of a group of people whose first encounters with Frank are with her diary, not just her image: women.

“What I condemn are our system of values and the men who don’t acknowledge how great, difficult but ultimately beautiful women’s share in society is,” Frank wrote on June 13, 1944.

“I think both Roth and Auslander do a bit of a disservice to Frank,” McLennan said. “Both of them make her a figure where it’s quite easy to fall into stereotypes about gender, a secondary character in the lives of male central characters.”

There is a fundamental maleness, too, in the way Gillham portrays Frank in “Annelies.” “I’m thirty-two,” she tells her sister Margot’s ghost as she applies lipstick. “In America thirty-two means cosmetics.”

Contrast that thin cynicism with Frank’s own critiques of female beauty standards, which she paired with a wry, intimate look at the pain those standards caused. “This is a photograph of me as I wish I looked all the time,” she wrote under a picture that she pasted in her diary. “Then I might still have a chance of getting to Hollywood.”

Is there any fair way of writing fiction about Frank? That question is tied to the biases of the authors who revive her; it’s equally linked to Frank’s particular, peculiar place in America. As the recently ousted New York Review of Books editor Ian Buruma noted in a 1998 NYRB Essay, perceptions of Frank’s diary in the United States came to be inseparable from two attempts to define the ideas her words ought to be taken to represent: that of Frank’s father, Otto Frank, and that of the American novelist and journalist Meyer Levin, who organized the diary’s publication in America and wrote the first version of its theatrical adaptation.

Image by Ulf Andersen/Getty Images

“Otto Frank wanted his daughter to teach a universal lesson of tolerance; and Meyer Levin wanted her to teach Jews how to be good Jews,” Buruma wrote. Through Otto Frank and Levin’s often-opposed efforts, the figure of Anne Frank became tied to the idea of an essentially American Jewishness. But at the time of her introduction, that identity was — as it remains — in flux.

No wonder there might be a particularly American mania for reducing her significance to a single compelling idea. In “The Ghost Writer,” Roth identified Frank as representing the American Jewish future as much as the European Jewish past. He was on to something. McLennan couldn’t think of another country that has matched the American interest in rewriting Frank’s story. As Prose put it, “America has this urge to screw with her image.”

That mania is linked to the desire to connect with Frank, the same desire that drove Auslander and Gillham to revive her. It’s as if forming that connection might reveal what the point of everything — the Holocaust, its aftermath, America — is.

For Auslander and Gillham, writing appeared to forge that connection where reading did not.

“By turning her into a, quote, ‘real person,’ I suddenly found a new connection to her,” Auslander said. Gillham first started a novel about Frank in the 1990s and returned to the project several times over the ensuing decades, only to encounter the same problem: “I couldn’t start writing about Anne. I started to orbit the character with all these supporting characters, but I just didn’t have the ability to go in and actually write her.”

Their model for coming to terms with Frank isn’t the only one available. Nathan Englander, for instance, whose short story “What We Talk About When We Talk About Anne Frank” first appeared in The New Yorker in 2011, approached Frank more obliquely. Englander’s story takes place in the house of a secular Jewish couple in Florida who are hosting Orthodox friends from Israel for a visit. It’s a fraught meeting, and as the foursome drink and dish, their conversation explicitly and implicitly explores some of the most sensitive questions of modern Jewishness.

Like Gillham and Auslander’s books, Englander’s story is rooted in a wish to better parse its author’s first experiences with Anne Frank. “My sister and I, we’re so American and so New York, and we, through our education, had real Holocaust-centered brains,” Englander told me. “If we met people, we’d ask, ‘Would they hide us?’ We’d call it the Anne Frank game.”

“Her character is [an] idea, and that’s what I’m exploring. What is it to pick a face and a person and make this your representative victim? What is it to use this girl because she is charming?”

Image by Ulf Andersen/Getty Images

Connecting to Frank as a person and grappling with her posthumous global significance are, as Englander hinted, discrete endeavors. Part of the difficulty with the novels that revive her is that they often try to do both things at once. Their authors’ outrage that Frank was offered to them as a symbol, not through her own vibrantly human writing, prompts their efforts to fictionally reintroduce her voice. That effort only ends up making Frank more of a symbol.

It also suggests that, at least for Auslander and Gillham, Frank became real only when they had the opportunity to mold her. “The argument has been made, over and over again, that it’s through the imagination that the Holocaust can be made to survive the inevitable detritus of history,” Ozick said. But she noted that certain subjects are so fraught that literary subversions end up reducing their meaning, rather than expanding upon it. “The rights of imagination are limitless,” she said. “[Anne Frank] is an exception, and that exception makes ‘limitless’ into a limitation.”

In recent years, women have begun to write these stories, too. In 2012, the television series “American Horror Story” aired the two-part arc “I Am Anne Frank,” the first episode of which was written by Jessica Sharzer, although series creator Ryan Murphy took credit for its premise. Set in an asylum, the episodes intercut the story of a psychiatric patient claiming to be Frank with that of a killer named Bloody Face, who wears a mask made of human skin. And there’s “The Secret Annex,” a play written by Alix Sobler, which premiered in Winnipeg, Canada in 2014.

“I used her name to make a point about how we observe our historical figures, and especially women,” Sobler told me. “The question I was wrestling with was: Is the impact of the diary worth one life?”

“You’re only paying attention because I’m writing about Anne Frank, and Anne Frank is only Anne Frank because she died at the end of the story,” she said.

Almost everyone manages to get back to that point. Even in “American Horror Story,” Frank (Franka Potente) tells a nun (Jessica Lange) “I could do more good dead than alive.” Roth’s Frank says nearly the same thing; so does Auslander’s. It’s a curious and telling attitude. If Frank’s words are meaningful only because she is dead, why pretend she’s alive?

Roth was explicit about the egotism involved in that endeavor. In “The Ghost Writer,” Zuckerman fantasizes about how his father might respond to his imagined marriage to Frank: “Anne, says my father — the Anne? Oh, how I have misunderstood my son. How mistaken we have been!” It’s apparent that Zuckerman’s primary interest in Frank is in her ability to win him love and attention. To a degree, Auslander and Gillham understand that same egotism, although they’re less willing to confront it. I asked Auslander what the real Frank might have thought of his version of her. “To be totally honest, I don’t think she’d give a shit,” he said.

This is what happens when Frank’s death is seen as the most meaningful part of her story. She comes to matter as a symbol, not as a person. Efforts to imagine what might have come next become responses to the pressures of contemporary Jewish life, the difficulty of conceptualizing the Holocaust decades after its end, fear of history’s ultimate indifference, fear of personal disaster, fear of personal irrelevance. Naive even at its most cynical, these efforts are a way of wishing that history could be different: less formative, less traumatic, less bad.

But history is formative, traumatic, bad. Can Frank’s legacy really benefit from those who try to wring new meaning from her loss? The most profound way to ensure her ongoing significance may simply be to read her words and then publicly grieve her loss, exactly as it happened. If you feel a civic duty to add your own voice to the chorus surrounding Frank’s story, consider Ozick’s advice: “Be a historian.”

If Anne Frank were alive, she would turn 90 in June. Her name would trend on Twitter. She would be interviewed on stage at the 92nd Street Y.

If her diary had been published just as it was, and she had lived, would she have become any less of a symbol? Jamie Birkett, editor of the forthcoming “Anne Frank: The Collected Works,” observed that the impulse to revive Frank has something in common with the instinct to question whether Shakespeare really wrote his plays. No one asks whether Frank wrote her diary, but every one of her fictional revivals is spurred by curiosity as to whether she was really as good as she seemed. If Frank were removed from the generative pressure of World War II, would she have written anything that special?

That question stems from disbelief that a girl could craft something so remarkable. It’s not an accident that it’s most frequently and audaciously been asked by men. And it’s not an accident that it’s men who, possessed by a desire to preserve Frank, overlook the extent to which she secured her own legacy. After all, her work was always marketed to girls. “People making Anne Frank survive,” McLennan said, “they’re just ritualizing what has happened anyway.”

Roth, Auslander and Gillham got something right. If Anne Frank had lived, just as she would never have been seen as “just Dutch, or just English, or whatever,” she would never have been seen as just a writer. She would have been the writer who was a victim, the writer who was a survivor, the woman writer. This year, as in all years, we will mourn the girl who died. If only we could give her the afterlife she deserves.

Correction, December 17 10:30 a.m.: A previous version of this article misstated the title of Rachael McLennan’s book. It is “In Different Rooms: Representations of Anne Frank in American Literature.”

Talya Zax is the Forward’s deputy culture editor. Contact her at [email protected]