First PersonRemembering a loved one through pots, pans — and pearls

A young bride inherits a set of Farberware pots and pans, and cooks up a lifetime of good meals and happy memories

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

My mother-in-law, Rachel, died suddenly 47 years ago, the year before I married her son. As the wedding approached, my future father-in-law, Joe, asked me to take anything I wanted to have of hers.

He had asked a few times during that dark year. Each time, I gently refused. Too soon. Too painful. Her loss was still an open wound. We were kids, 20 years old. How could I take anything from the life that was hers, from the home that was her hard-earned labor of love?

I had met her five years earlier. Her son, Marty, was my boyfriend. We were in the same ninth grade class of a small Jewish high school in Montreal. I loved her humor and warmth, respected her intelligence and strength. With two men in the family, she welcomed the opportunity for girl talk, eager to show me her new outfits or jewelry. I was a frequent dinner guest. We chatted and laughed as she tended the pots simmering on the stove. She made me feel like family.

When Joe insisted that I choose what I want without further delay, I asked for her pots. The ones she cooked in all the time. The ones her perfect boiled potatoes emerged from. He looked baffled. He had expected me to ask for jewelry, or things of greater value. I remembered the luminous, double strand of pearls she had modeled for me, restrung with a beautiful new clasp. It made me cry. I asked Joe to give Marty anything else he wanted us to have.

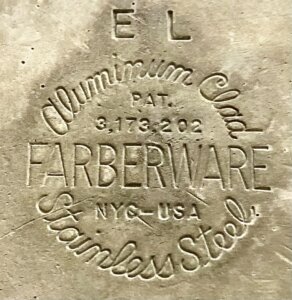

‘Farberware — from America’

I didn’t know how to cook. But I knew I wanted those pots. I could picture Rachel, beaming, as she told me their story when I admired them: “Farberware — from America,” a provenance that made them instantly glamorous. But they were also better at cooking.

Their aluminum bottoms heated rapidly and evenly. On the inside, those bottoms were clad in stainless steel that extended upwards to form the walls of the pots. The steel interior protected acid foods (like tomato sauce) from off-flavors that developed when they interacted with aluminum. It also made cleanup simpler.

She told me her sister, Sally, lived in New York and worked at A&S, a local department store. She had used her employee discount to buy these pots for herself. Loving them, she had brought Rachel a set like hers when she came to visit in Montreal.

This was Montreal in the late 1960s. No one in our small immigrant community had such pots. My mother’s pots didn’t simmer and sizzle this way. These were better.

Rachel and her sister, like Marty’s father and my parents, were the only ones in their family that had survived Poland’s Holocaust. They lived 400 miles apart, but had many of the same things in their homes. I think it shortened the distance between them, making it easier to share their lives between long-distance calls, an expensive luxury then.

Cooking up memories and meals

After we married, I cooked our first meals in those pots. Watching over them, stirring, was a comforting way to think about Rachel through the sadness. I could see her cooking and holding and washing them. I liked to remember her that way. I hoped she knew how hard I was trying to make potatoes as good as hers.

Over the years, wherever we moved, Rachel’s pots helped our new place feel like home. A year after our marriage, when we arrived in Minneapolis for graduate school, I unpacked them immediately when I set up our tiny new kitchen. Five years later, their box, labeled “PRIORITY,” in big block letters, was unloaded first when the moving truck arrived at our house in Pittsburgh. They moved with us to Chicago, the city that has been our home for more than 30 years.

As my life unfolded, I learned to cook. I sought out pans with greater heft, that felt solid and balanced in my hands. I acquired cast-iron pots from France and professional-grade American pots and pans that I take great pleasure in. They conduct heat magically, responsive to minute flame adjustments. They make me a better cook than I really am.

Replacing the pots over time

Rachel’s pots are still with us, though not the full set. Over the years, the skillets’ handles cracked, and they had to be retired, replaced with pans better designed to sear and cook without burning. I use the surviving Farberware trio (2-, 3- and 5-quart pots) for less ambitious tasks — cooking foods in boiling water — like hard-boiled eggs and potatoes. Rachel’s boiled potatoes are still the gold standard, but mine are respectable now.

To reduce storage space, they nest inside each other in the cabinet near my stove. There, they keep company with their more highly evolved companions. But they are no less respected or cared for. Every few weeks, I use a small screwdriver to gently tighten their handles, which have developed a tendency to loosen. I worry about the screws that keep the handles attached. They are starting to show signs of wear from this regular maintenance.

I do have more than Rachel’s pots. In addition to some objects she loved, Joe gave me her jewelry. Over the years, I grew into her beautiful pearls. I wore them on many happy occasions, including my daughter Rachel’s bat mitzvah, and her brother Joe’s bar mitzvah. Yet even now, it’s the pots, not the pearls, that evoke the most vivid memories of her life when I knew her.