Why is Ben Shapiro so worried about Satan in ‘Paradise Lost’?

The conservative talking head went on a lengthy Twitter rant about John Milton’s epic poem

Sam Smith in his very threatening devil horns at the Grammys. Courtesy of Getty Images

It’s still a mystery to me why Ben Shapiro decided to pop off about John Milton. The conservative talking head does not usually do a lot of close reading of abstruse old English literature.

It had something to do with the Grammys, where Kim Petras and Sam Smith’s performance of their hit “Unholy” caused a conservative furor and a lot of accusations of Satanism thanks to their red costumes and campy devil horns.

But Shapiro, a conservative podcast host and the founder of right-wing outlet The Daily Wire, picked up that thread with a barrage of tweets about Satanism’s roots in Milton’s 1667 epic poem Paradise Lost.

“For most of religious history, Satan was the great villain, an emblem of rebellion against the Good and the True, a symbol of resistance to the Holy,” Shapiro tweeted. “When John Milton wrote ‘Paradise Lost,’ (1667) his Satan famously stated, ‘better to reign in Hell, than serve in Heav’n.’ Satan was the villain of the piece, abandoning the Good and the True for a personal sense of power.”

He went on to argue that people today worship the wrong things — “liberty” and “happiness” — which are the values Shapiro says Satan stands for. But for many people, particularly many Americans, Satan’s stated values are their own goals. And the very quote Shapiro uses to show Satan’s evil actually makes Lucifer’s case pretty compellingly; as Revolutionary War hero Patrick Henry famously said, “Give me liberty or give me death!”

Don’t fight the culture wars, they say. Meanwhile demons are teaching your kids to worship Satan. I could throw up.

— Liz Wheeler (@Liz_Wheeler) February 6, 2023

pic.twitter.com/p1rqEwVeSW

Realistically, it’s a stretch to connect any of this to a campy Grammys performance about doing “unholy” things in bed. (Lil Nas X’s music video for “Montero,” on the other hand, draws pretty directly from Paradise Lost, and also Dante’s Inferno; I recommend it.) But I wrote my undergraduate thesis on Paradise Lost, so I’m going to do it anyway.

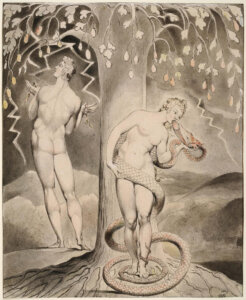

Paradise Lost tells the story of the Fall: the creation of the world, the birth of Adam and Eve, their temptation by the serpent and their subsequent eviction from the Garden of Eden. It’s a biblical story, but Milton embroiders it a lot. To give you a sense of how much he added: The epic poem covers the events of the first three chapters of Genesis, less than 100 lines of text; Paradise Lost is over 10,000 lines long.

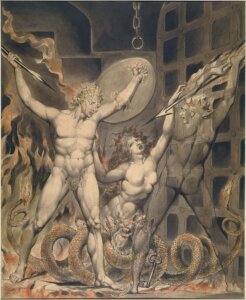

A lot of what Milton added will be familiar — the story of Lucifer’s battle with heaven and fall to hell, for example. But his most influential addition is giving his famous characters compelling motivations and complex personalities. His legions of demons are fleshed out, emotional, relatable, and none more so than Lucifer, who strives to escape the tyranny of God in his quest for liberty, knowledge and independence. Meanwhile, Milton’s God is, well, kind of tyrannical: strict, egotistical and austere.

Some people see this as a metaphor for the fact that following the way of the Good and True, as Shapiro put it, is difficult, and sin is tempting; they argue that Milton made Satan a sympathetic character, with relatable values to show exactly why he is so dangerous.

But others see an anti-Christianity message in the epic. As poet William Blake wrote of Milton, he was “of the devil’s party without knowing it,” and his Satan is so compelling because Milton himself couldn’t help but see the Goodness and Truth in Lucifer’s desired life of freedom, self-governance, knowledge and pleasure. God proposes obedience, Satan proposes freedom, and the freedom, Blake believes, is more moral.

Shapiro juxtaposes ideas like “happiness” and “authenticity” against “religion and morality” in order to show that the left, with its love of pleasure, is composed of Satanists, and society is broken. (Like many political talking heads, he likes to overstate his case a bit.)

When John Milton wrote “Paradise Lost,” (1667) his Satan famously stated, “better to reign in Hell, than serve in Heav’n.” Satan was the villain of the piece, abandoning the Good and the True for a personal sense of power.

— Ben Shapiro (@benshapiro) February 6, 2023

His argument isn’t very compelling — Who would sign up for a belief system fundamentally opposed to happiness? — but it’s also not based in reality. Shapiro presents religion as the voice of morality, but he offers no actual moral beliefs to justify that assertion. Religion, in his formulation, is moral because it’s religion, and religion is moral; it’s tautological. Things that are defined as against God — like Satan — are evil by definition, regardless of what values they stand for. Even if those values are pretty compelling. Apparently it’s impossible to assess morality independently of religion.

But religion need not depend on obedience. And it has space to embrace freedom. Shapiro should know that, as an Orthodox Jew. Judaism is based on a strong tradition of arguing about values; God is fairly irrelevant to Jewish choices on a day-to-day basis. Instead, traditions are determined by the Talmud, which is basically a canonized book of centuries of human debate over right and wrong. There’s no rigid authority, and everything is explained at length, with many examples and counterexamples.

In fact, in one famous Talmud story, “The Oven of Akhnai,” a set of rabbis rejects God’s opinion. But God does not smite them for disobeying; instead, God smiles while saying “my children have triumphed over Me.” Milton’s God is not present in Judaism.

Perhaps Milton’s Lucifer was threatening to Christians of his time, but he sounds sort of aspirational for Jews. Maybe Shapiro needs to go back to the books for a refresher, whether that’s the Talmud or Paradise Lost. Either will do, really.