The crucial Jewish ingredient that you probably don’t think of as a Jewish ingredient

Want to make shakshuka, matzo brei or avgolemono? You’re going to need some eggs

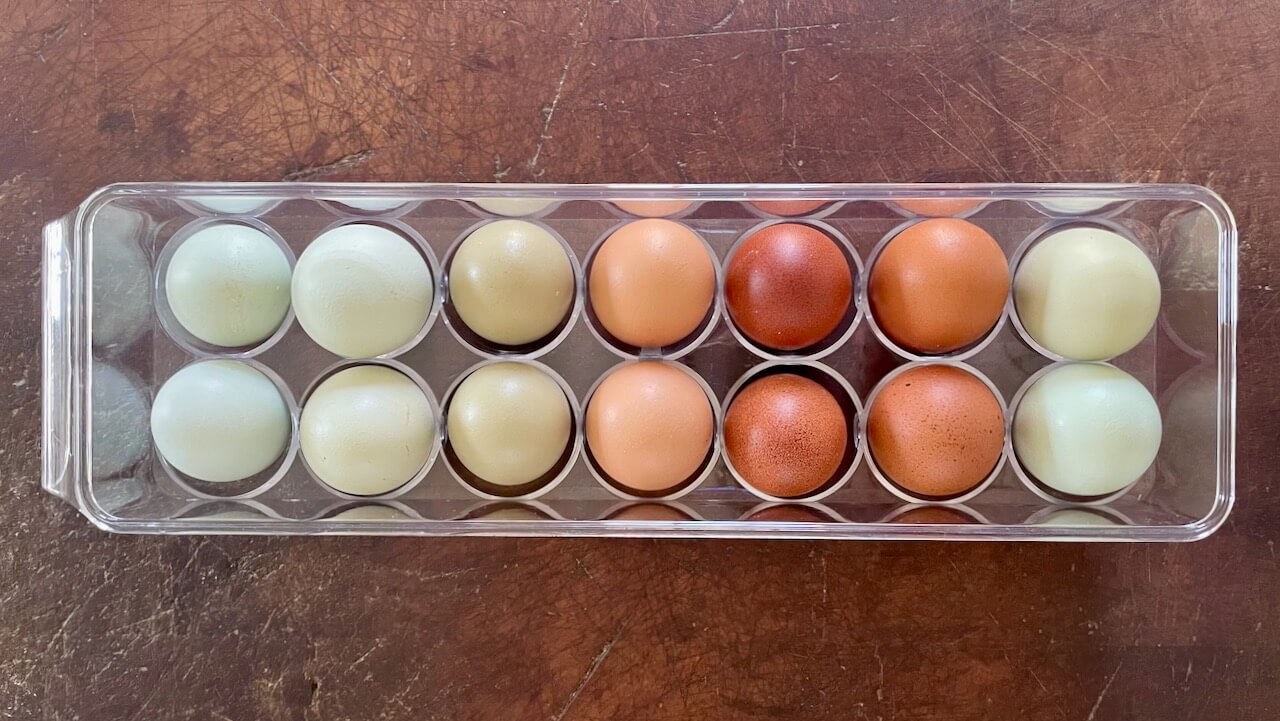

The egg features prominently at the Passover Seder. Photo by Liza Schoenfein

As contenders for a spot on the Iconic Jewish Ingredients list, eggs at first glance seem overexposed. They’re a critical component of almost every cuisine on Earth, which raises the question, “Where to begin?” Or maybe even, “Should I?”

Eggs play a major part in so much everyday fare. They’re fundamental to noodles, baked goods, ice cream, custards, soups and sauces. They take pride of place on the breakfast plate and hold their own at lunch and dinner too.

Yet they don’t exactly scream “important Jewish ingredient!” — or maybe we’re just not listening.

Eggs are a parve protein, meaning they can be consumed by kosher-observant Jews as part of either dairy or meat meals. As such, they appear across the Jewish culinary landscape, from the baked-egg dish shakshuka, which came down from North Africa and settled in Israel before appearing on menus seemingly everywhere, to the savory Georgian cheese-filled, eye-shaped pastry called khachapuri (the pupil in this metaphor being an egg yolk) to the Sephardic slow-roasted eggs called huevos haminados that appear alongside Yemeni kubaneh and jachnun breads; over sautéed greens; and nestled into long-simmered stews such as hamin.

Eggs are not only packed with nutrients, they’re loaded with cultural and spiritual significance. They make us think about beginnings — and endings. A potent symbol of renewal, rebirth, fertility and the cycle of life, they are also a symbol of mourning.

The egg features prominently in the springtime holiday of Passover (and, not incidentally, Easter), when the saltwater into which many Jews dip hard-boiled eggs at the Seder recalls the tears and sweat of their enslaved ancestors in Egypt. The roasted egg on the Seder plate — in addition to reminding us of death and renewal — represents the festival offerings that were once brought to the Temple. (The word egg in Aramaic is b’ey’a, which also means pray and please.) And not unlike the Jewish people throughout history, its shell is both fragile and strong.

Of course the egg is not all symbolism and intensity, and Passover, for all its mighty significance, is not without its simple delights. Very high among those, of course, is matzo brei. (Cue culinary flashback.)

Every time I think of matzo brei, I’m transported straight to my grandparents’ kitchen in Longmeadow, Massachusetts, where I’m perched on a stool at the avocado-colored counter breaking sheets of matzo into crackling shards over a mixing bowl as my mom’s stepfather, my Papa Max, stands beside me lovingly narrating his matzo brei-making process.

We cover the pieces of matzo with warm water before draining and patting them dry. In a separate bowl we crack and whisk eggs into which Papa, who avoided salt and adored anything spicy, grinds a slightly worrying quantity of black pepper. We combine the eggs and the matzo, then fry everything up in a big skillet slick with sizzling margarine. Sometimes, little cubes of Hebrew National salami made their way into the pan too.

I adored this peppery matzo brei — almost as much as I adored Papa Max — but it’s not the only Passover dish that relies heavily on eggs. Eggs are key to many Passover desserts, where they provide moisture, structure, and even leavening.

Another of their little magic tricks is that they can be used as a thickener. Whereas soups, sauces, and stews are often thickened with flour or cornstarch, they can also achieve that body with the addition of beaten egg. (The lecithin in egg yolks acts as a thickening agent.)

The classic example of this alchemy is found in avgolemono, which we generally think of as a lemony Greek soup but which actually refers not to the soup itself (which is technically called kotosoupa or kotosoupa avgolemono) but to the lemon-and-egg mixture that flavors it and gives it its thick, creamy consistency.

This mixture is in fact a mainstay of Sephardic cuisine called agristada, which originated in Spain and traveled with Iberian Jews escaping the Inquisition to Turkey and Greece, where it eventually became avgolemono. According to Joyce Goldstein in The New Mediterranean Jewish Cookbook, it’s one of the most commonly used sauces for fish dishes in the Sephardic world, and “is also used in meat meals, where dairy products are prohibited, in place of béchamel, beurre manié, or cream.”

The soup we know as avgolemono is called sopa de huevo y limon in many Sephardic kitchens and is sometimes made with beef or lamb in place of chicken, and with vermicelli or other pasta instead of rice. It’s traditionally served to break the Yom Kippur fast, and at Passover crumbled matzo can stand in for the rice or pasta.

Years ago I shot a series of cooking videos for E-How, and one of the recipes I developed was for a very easy, very delicious Greek chicken-lemon-rice soup. Evidently a lot of folks wanted to learn how to make this soup, because when I found it on YouTube in the course of researching this article, I saw that the video had garnered over 25,000 views. You can check it out here, and follow along with the recipe below. Feel free to substitute crumbled matzo if you’re avoiding rice at Passover.

Not-Just-Greek Chicken-Lemon-Rice Soup

What makes this recipe so fast and easy is that it calls for already-cooked chicken and rice. I love to make it when I have leftovers because it comes together so quickly. Of course you are welcome to cook your own chicken and rice — and even make homemade chicken stock if you’re so inclined. But I promise, you won’t be disappointed with the results if you keep it simple.

4 cups low-sodium chicken broth

2 cups shredded cooked chicken

2 cups cooked white rice

2 eggs, beaten

3–4 tablespoons fresh lemon juice (the juice of one large juicy lemon)

Salt and pepper to taste (start with ½ teaspoon of salt and go up by ¼ teaspoons from there)

Chopped fresh parsley and/or dill for garnish

- Heat chicken broth in a pot over medium heat.

- In a small bowl, combine egg and lemon juice and whisk to combine. When broth is at a low simmer, add a ladleful (½ cup to 1 cup) to the egg mixture and whisk to combine. (This step is crucial. If you add the egg mixture straight to the broth you’ll end up with egg-drop soup.)

- Slowly pour the egg mixture into the pot while stirring the soup. (If you do happen to end up with pieces of cooked egg, strain the broth before proceeding with the next step.)

- Add the chicken and rice, season with salt and pepper, and simmer for a couple of minutes without letting the soup boil, stirring occasionally. The soup will thicken over the next few minutes. Taste and adjust the seasoning, adding additional salt, pepper, and lemon juice as desired. Pour into bowls and garnish with herbs.