How Ayn Rand, Emerson and Thoreau perverted the American Dream

In ‘Bootstrapped,’ Alissa Quart takes aim at our myths and our solipsism

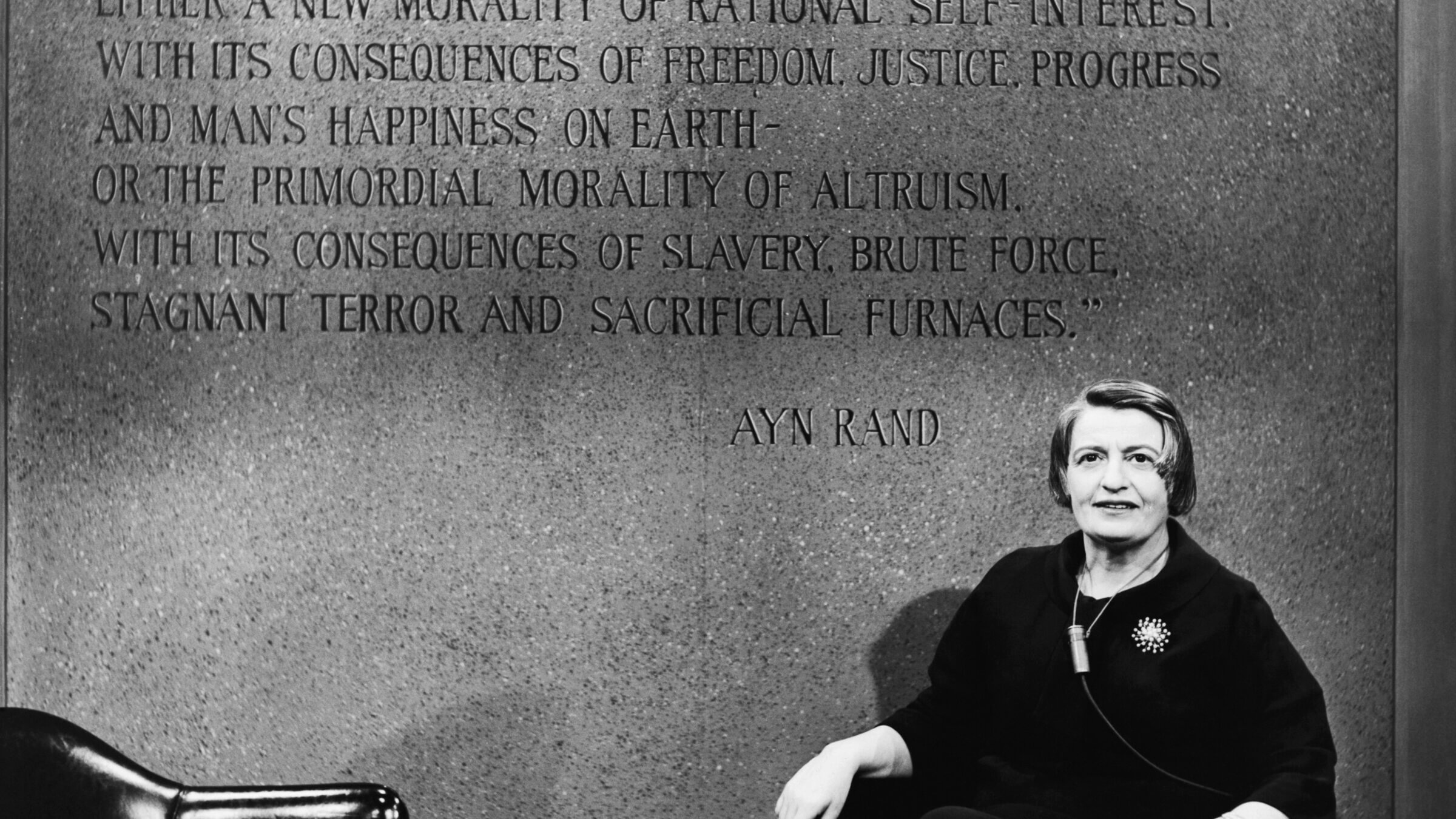

Ayn Rand on the set of The Today Show, 1961. Photo by Getty Images

Living upstate and away from her people at the onset of the pandemic, Alissa Quart found community in a Passover zoom Seder. In the face of a contemporary plague, finding thoughtful company to discuss ancient and modern hardships was a natural move for a “Jewish social justice crusader.” After all, no one wants to face unforeseeable calamities alone.

In her new book, Bootstrapped: Liberating Ourselves from the American Dream, Quart lays bare the laughable linguistic roots of the term “bootstrapped” and its dangerous contemporary sociological ramifications. It may originally have been coined to show that, just like blowing your own sails, lifting yourself up by your bootstraps is actually impossible. But today the myth of the self-made man is twisted through modern society, feeding off the American Dream and scorning everything that’s not “self-reliance.”

Part of the reason that Jews, more than any other ethnic group, continue to vote for Democrats, is that one of our decisive annual ceremonies is the Passover Seder. During the recounting of that story of the Exodus, Jews of all stripes are reminded that they began as slaves, became immigrants alongside a crowd of non-Jews (the “Erev Rav”), and narrowly escaped death in the wilderness only to be feared as foreigners in the Promised Land which their leader cannot enter because of his own hubris.

In terms of both theme and diet, Passover sets a tone for a community. It is no season to be puffed up about one’s own singular achievement. Even the feast itself is a celebration of the group coming together to achieve a communal gathering. Traditionally, though presented as a group undertaking, the preparations are overshadowed by the noisy Seder itself. The feast, the cleaning of the home and the exorcism of any leavened products has been a task taken for granted and performed laboriously, by women.

These types of domestic labor — along with other forms of privilege — are exactly the things that Quart accuses Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson of erasing from their accounts of their own ideas of self reliance. She skewers their pomposity in ignoring the “role of wealth, gender, race, inherited property and a whole cache of related opportunities.” Indeed, she connects some compelling dots between the storytelling of the transcendentalists that she had so admired as an English major and “the pernicious parable of the deserving rich.”

These admired writers from history lying or providing cover for a broken society feels like a particular betrayal for Quart — a poet, journalist and author of such books as Branded: The Buying and Selling of Teenagers and Squeezed: Why Our Families Can’t Afford America. As the executive director of the not-for-profit Economic Hardship Reporting Project, she is in particular touch with the types of erased, obscured and ignored stories of Americans living in precarity. And, in Bootstrapped, she explains the history of the American myth of self-reliance and how it endangers tens of millions of Americans today.

Her implication is that whatever the good intentions of people in the C-suite may be, they are fighting against a myth bent on rewarding the personally lucky and the historically privileged. Noting that over $625 million had been raised for health care through GoFundMe, Quart quotes its former CEO Rob Solomon saying that “We weren’t ever set up to be a health-care company and we still are not.”

However, in 2016, while he was still CEO, Solomon wrote about the mission of GoFundMe as a type of “tikkun olam — that each person should work towards making the lives of others and those of future generations better through acts of loving kindness.” His motive seems genuine and aligned with GoFundMe’s mission, but Quart’s point is that even the millions of dollar bills it raises are little more than “Band-Aids.” To her mind, and mine, it is an admission of gross social failure when tens of thousands of people in the richest society the world has ever known need to turn to a private fundraising company to raise cash for emergency medical procedures.

Fascinatingly, after Emerson and Thoreau, Quart presents Alisa Rosenbaum as the key proponent of American solipsism. Better known as Ayn Rand, Rosenbaum’s novels are the most widespread modern source of the brutal social myth that “I am not my brother’s keeper.” It is fascinating to speculate on how a Russian-Jewish immigrant like her, whose success was so dependent on family, education and Hollywood networking was able to focus and amplify such a gospel of privilege.

It may be that it was precisely the elements of dependency that Rosenbaum wanted to escape. Perhaps for Rosenbaum and other self-proclaimed self-made Americans, shame and disgust come from the feeling of owing your success to the others who have built the roads, the lines of communication and the freedom for Jewish women to publish fiction.

In her bestselling novel The Fountainhead, Rosenbaum hides her name, heritage and gender as author. And, tellingly, her protagonist and stand-in Howard Roark is a healthy, young, white, male atheist with no minority affiliations. She even chooses a nom-de-plume that means “nothing” in Hebrew to demonstrate her absolute lack of connection to what comes before. Quart notes that, as Rosenbaum’s luck faded and she needed the help she had not while riding her wave of health and fortune, so in “absolute contradiction to the values she spent her life peddling, Rand turned to Social Security — there are freedom of information act documents that confirm she received the assistance.”

Rand’s story is a particular case of disavowal, but Quart is thinking about the general psychological attraction of the “bootstrapping” myth to a broader audience and quotes theorist Jacqueline Rose saying that “motherhood is ‘the ultimate scapegoat for our personal and political failings, for everything that is wrong with the world.’” The myth of self-making is not only systemically misguided and injurious but also one that cuts at the heart of the family. Perhaps too, the strength of the myth of the Yiddishe Mama in the Ashkenazi community has inoculated American Jewry somewhat from the inherent social disavowal of the “mother” as part of the American Dream.

A significant part of the book, though, is not spent in critique. Quart is committed, both literarily and professionally, to describing how things can be made better. She goes deeply into the myth and the system it has helped to build, but she makes real concrete policy suggestions which lie beyond the scope of this essay, though readers should feel free to discuss their merits over the Seder Table. In Bootstrapped, Quart does not just ridicule the idea of raising a society up by its bootstraps but presents ways — like cooperatives, collectives and mutual aid societies — by which we might indeed raise our standard of living. After all, there’s no point in critiquing Pharaoh if you don’t actually have a plan of how to reach the promised land.