What Ben Platt learned reading Leo Frank’s letters

Paying a visit to YIVO, the ‘Parade’ star comes face to face with history

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

Eight times a week, Ben Platt spends around 15 minutes writing onstage at the Bernard B. Jacobs Theatre in the musical Parade. Somehow he knew to write in cursive.

Confined to a jail cell in the role of Leo Frank, Platt jots down whatever’s going through his head in the moment — that the audience is good that night, that his co-star Micaela Diamond made him laugh in the previous scene, that a song went really well. As Platt writes, in a notebook he hopes to keep at the end of the show’s run, his character is fighting for his life.

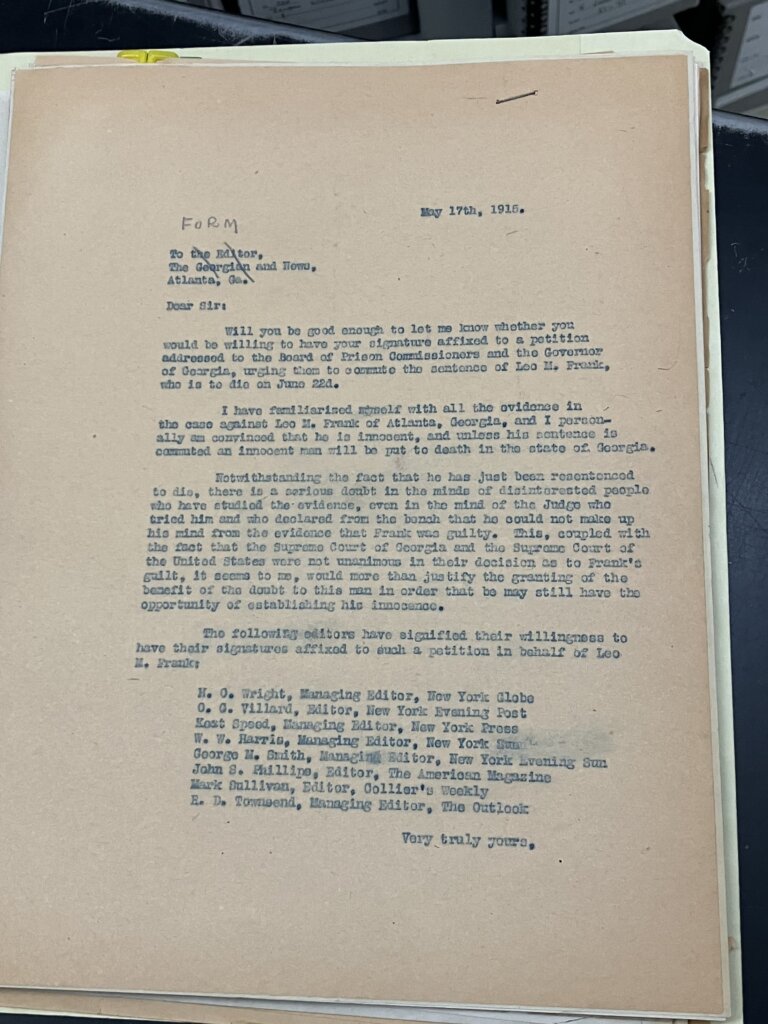

Frank, a pencil factory supervisor sentenced to death for the murder of a 13-year-old employee, spent two years in prison working to appeal his conviction, writing countless letters to well-wishers who believed in his innocence. Frank’s sentence was commuted to life in prison in 1915, and then an antisemitic lynch mob hanged him that August. Frank’s case was a flashpoint, birthing the Anti-Defamation League and the revival of the Ku Klux Klan. Doomed to become a martyr, Frank’s letters speak to something unexpected: hope.

Platt, 29, the same age Frank was when he was arrested, walks into the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research wearing a brown corduroy jacket, white Reeboks, white pants and a white T-shirt adorned with abstract art (“a thrift shop purchase,” he says). He snaps a picture of YIVO’s current exhibit, “Am Yisrael High,” about Jews and cannabis, and sends it to his fiancé, the actor Noah Galvin.

Platt is here to look at Leo Frank’s letters, but even before he arrives at the archives, he finds a reminder of Frank’s story in a hallway. Observing the antique card catalogs lining the wall, he gingerly opens a drawer and pulls out a card that has the name “Minnie” on it.

“That’s the name of their housekeeper at the beginning of the play,” Platt says. “That’s random.”

Stefanie Halpern, director of the YIVO archives, leads Platt into the stacks, with their deep rows of gray acid-free boxes, and explains the institute’s origins and mission. It was founded in Vilna in 1925 to collect and study “the stuff of everyday Jewish life,” relocated to New York in 1940, and managed to retain a fair amount of its original collection with the help of the Paper Brigade, the Vilna Ghetto’s book smugglers, and the Monuments Men.

Platt asks questions — was it only after the war that YIVO began collecting non-Yiddish artifacts?

“Actually, people from across the world sent material to YIVO,” Halpern says. “A lot of it related to theater.”

Platt says he’ll have to come back for that.

After the spiel, Halpern places a folder on a cart.

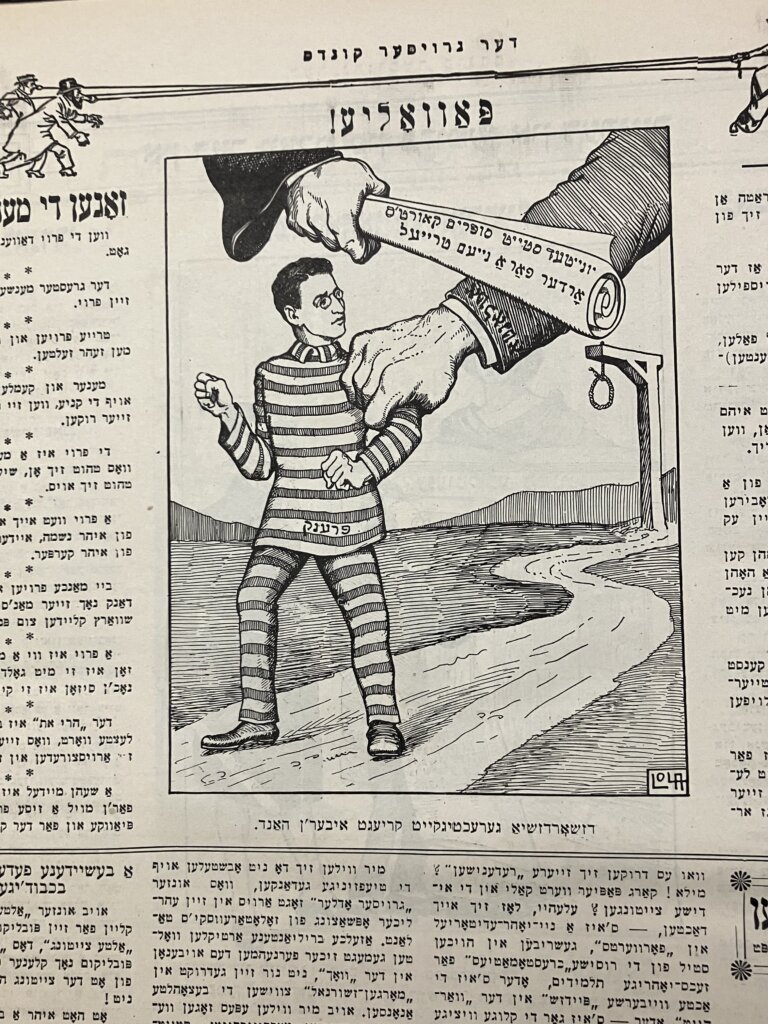

“This case, as you know, made headlines in the press, and the Yiddish press was also extremely interested,” she says. “Even, in the case of Abraham Cahan, the founder and editor of the Forverts, visiting Frank in jail. We have a series of letters from Leo Frank to Abraham Cahan.”

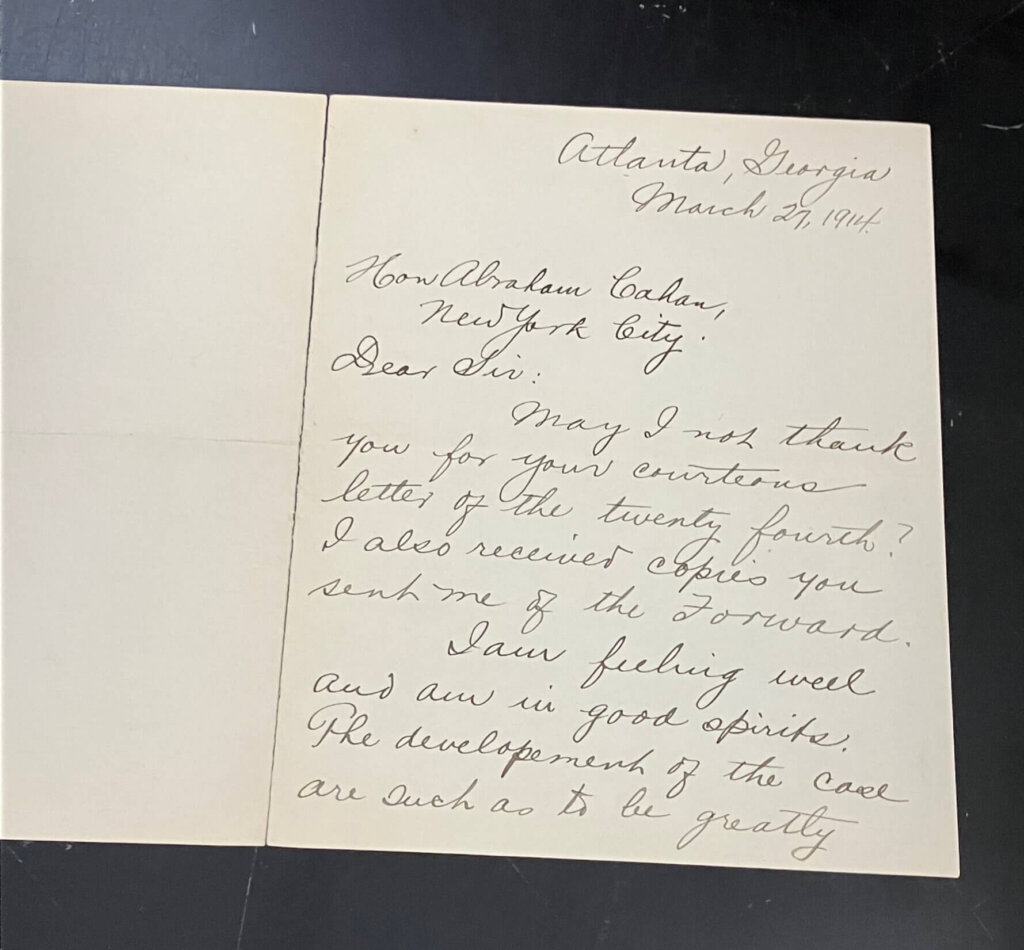

Halpern pulls out the letters, kept in plastic sleeves and hardly yellowed.

“His penmanship is so in-cred-ib-le,” Platt says, carefully lifting the pages. “I had some feeling that he just had a gorgeous penmanship, and of course he does.”

Platt reads a letter dated March 27, 1914, under his breath: “I’m feeling well and am in good spirits. Developments of the case are such so to be greatly encouraging. As you know, the truth must out.”

“Oof,” Platt says. “He’s so hopeful.”

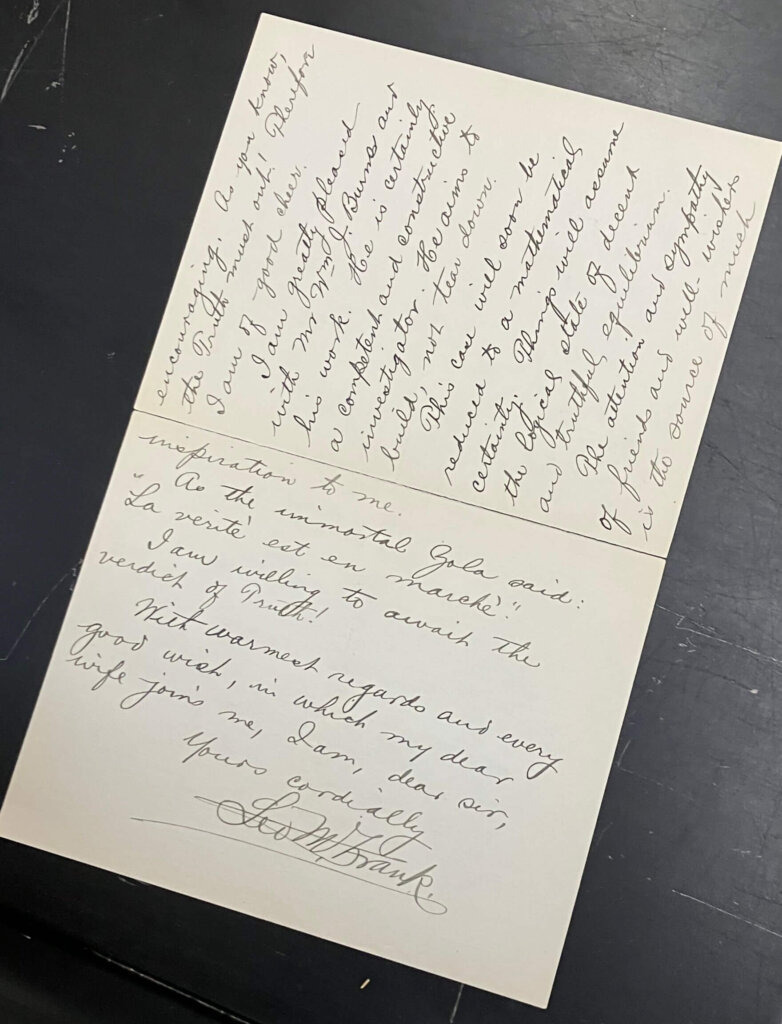

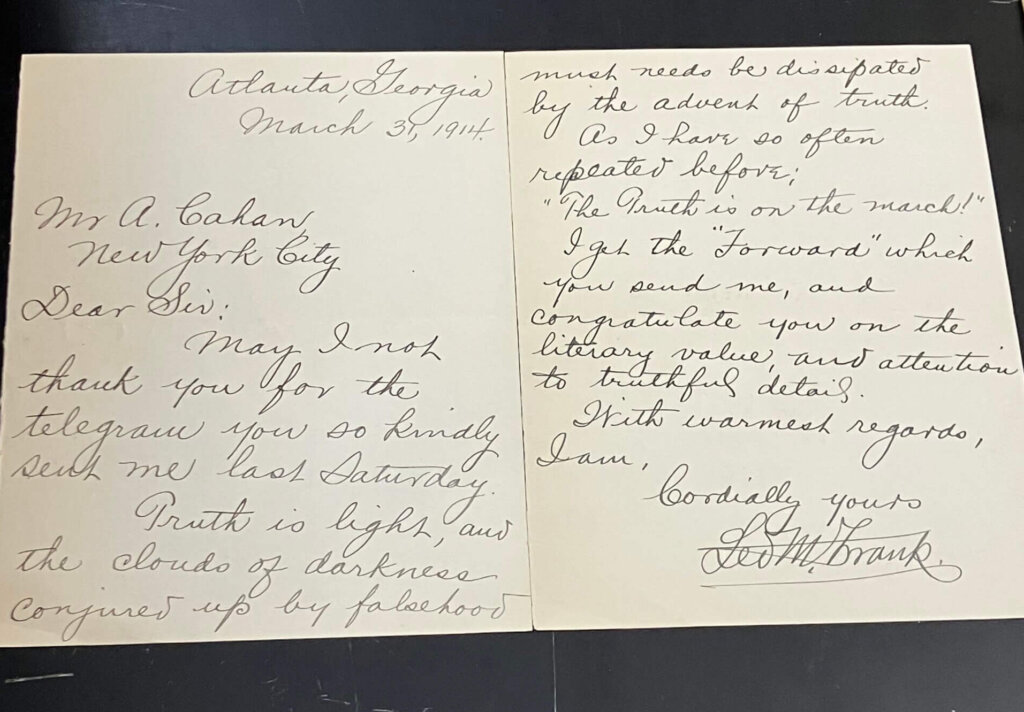

He asks if he can take a picture to send to his family. Halpern takes the letters out of their sleeves and Platt snaps them with his iPhone. He reads a second letter to Cahan, which says, “As I have so often repeated before: ‘The truth is on the march.’”

It’s a favorite quote from Emile Zola, “La verité est en marche.” Zola wrote it in J’Accuse, his indictment of the French government in the Dreyfus Affair. In that case, the truth did prevail — albeit belatedly.

‘Everybody could feel it coming — except for Leo’

While there was little doubt Dreyfus’ persecution was rooted in antisemitism, Cahan’s own interviews with Frank, conducted in Frank’s jail cell in 1914, reveal that Frank didn’t see his conviction as the result of bigotry.

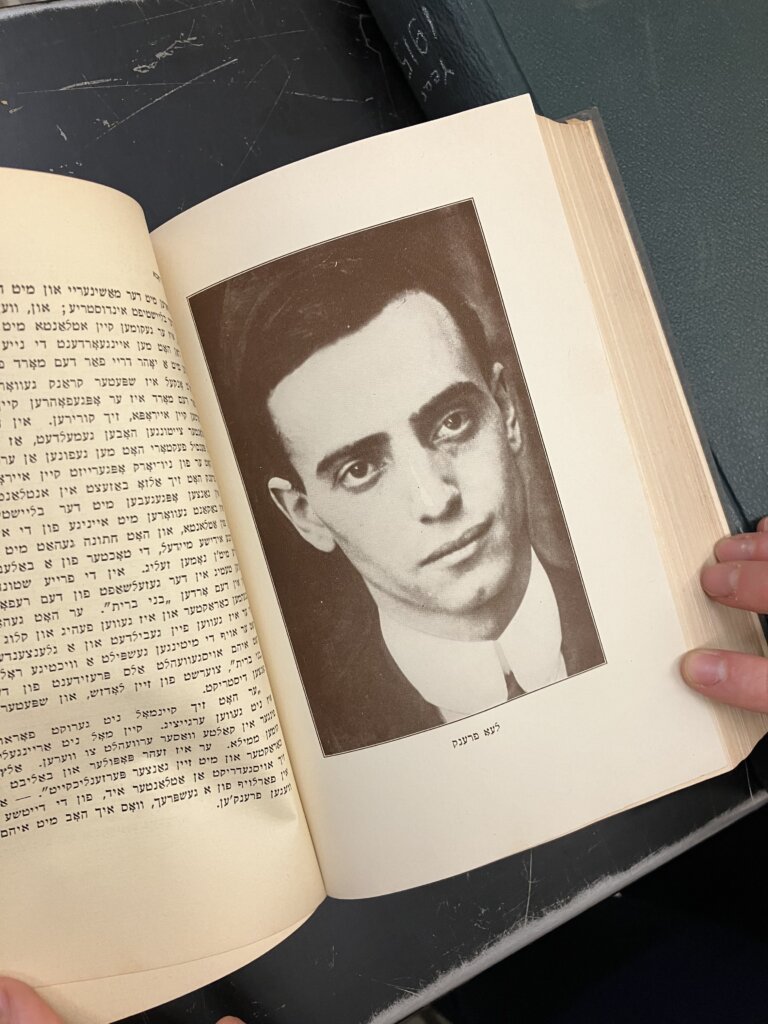

Halpern lugs out the fifth and final volume of Cahan’s memoir, leafing through the book to show images of the murdered girl, Mary Phagan, along with Frank and Georgia Gov. John Slaton, who commuted Frank’s sentence. Platt can read Hebrew from his time in day school (Los Angeles’ Sinai Akiba Academy), and picks up on the Yiddish. “I love the transliteration,” he says, then reads with a Yiddishe lilt — “Guh-vornor Slahten.”

Cahan, a socialist born in the Russian Empire and no obvious advocate of the factory manager class, devoted 250 pages to the Frank case. Together with his editorials for the Forverts, they show a man haunted to witness the hatred he knew in Europe emerging in America.

Frank had a different take on his ordeal.

“Antisemitism is absolutely not the reason for this libel that has been framed against me,” Frank told Cahan, claiming the police harassed him because they lacked for other suspects and, only then, thought to “take advantage of my background too.”

“Well that is antisemitism,” Platt says, reading from an English translation.

In the musical, with a book by Pulitzer Prize-winner and Georgia native Alfred Uhry and a score by Tony-winner Jason Robert Brown, Frank sings, “How Can I Call This Home,” about the alienation he feels as a Jewish Yankee in the South.

Asked how the account in Cahan’s memoir squares with the character he’s playing, Platt says that there is a meaningful difference.

“Because of what the show is trying to accomplish, I think he has to be a little bit more aware of the profiling,” he says.

Frank, as written by Uhry, whose grandmother played canasta with Frank’s widow, has the same fire for the truth — if charged with a more potent contempt for the South and its ways — as the man in the letters.

“I do think there’s this slight fictionalization of him being very aware of his Judaism being the thing that sets him apart,” Platt says. “But it does sound like even in the midst of him being like ‘it’s not about antisemitism,’ he’s very aware that he’s not a full Southerner, he’s not a full Christian, he’s a Brooklyner.”

Halpern shows Platt a folder from Herman Bernstein, the editor of the Yiddish daily Der Tog. Bernstein, she explains, was active in clearing Frank’s name. Among his archives is correspondence with Slaton, asking him to comment on the “anti-Jewish feeling” in Georgia that “has blinded the unthinking masses.”

“Everybody could feel it coming — except for Leo,” Platt says.

Bernstein’s file also contains a letter asking newspaper editors to sign a petition in Frank’s defense and, of particular interest for a man dramatizing Frank’s life, telegrams in which Bernstein alerts Frank to a play and a film about his case that Bernstein was able to stop.

“It would have indeed been most lamentable if either of these things had been aired in public,” Frank wrote back about the movie and play, signing it “LMF/Mrs LMF.” Elsewhere he signs off “with warmest regards and every good wish, in which my dear wife joins me.”

“He always says his wife joins him,” Platt observes. “Any time he mentions Lucille it just gives me shivers. There’s just clearly such a loving relationship.”

At the center of Parade is a love story. The prickly Leo has trouble relating to Southern Jews like his wife, Lucille (played by Diamond), and often snaps at or berates her. But in the second act he finds in Lucille an unwavering champion. Right as their love for one another is at its brightest, the lynch mob breaks into Leo’s cell.

To prepare for playing Frank last fall at City Center, Platt read Steve Oney’s book about the Frank case, And the Dead Shall Rise, and, before the show opened, visited Frank’s family home in Brooklyn, which is still a residence.

Now in YIVO’s rare book room, surrounded by leather-bound tomes, Platt says he treated the historical context as a “backdrop” for his performance, and the libretto and score as a “primary text.” Michael Arden’s production is steeped in documents, using projections of headlines from the Georgia press and archival photographs of the historical characters.

Asked how the letters differ from other research, Platt says they are much more immediate.

“You just feel an instant connection to someone when you see their penmanship and the way they speak and the actual object — it’s so irrefutable,” says Platt. “Obviously you see photos and you see writings about it and it feels real in your mind, but then doing things like seeing his home and now especially seeing his own — where his hand was — it feels really confronting in a really meaningful way and sad way and happy way.”

‘This is very urgent’

Platt’s first introduction to Parade was the rousing Act II duet “This is Not Over Yet,” which was in the show tune rotation in the Platt family car. It took time before he understood the context, in which Leo and Lucille, receiving good news, sing of hope — suddenly, finally, “loud as a mortar.” Platt picked up more information in high school drama class (he’s an alum of Harvard-Westlake in LA.) In 2009, he saw a production at the Mark Taper Forum in Los Angeles and, haunted by a photo of Frank on the playbill, did some online research.

Platt says that returning to Broadway with this material, his first outing since his Tony-winning turn in Dear Evan Hansen, was a deliberate choice for “a myriad of reasons.”

“One of them definitely being that it’s a story worth telling, one of them that I feel given my background and my Judaism and my particular abilities and my age and many things about me, I really felt I was the right vessel for this particular character,” says Platt.

Following his success in Evan Hansen, Platt thought he could, perhaps, draw crowds with any project he picked. He sees it as a responsibility, as well as a privilege, to be able to command an audience. The show moved from a week-long engagement at New York City Center to a six-month run on Broadway with hopes to reach as many people as possible.

“A subscriber audience of Jews would love this show and we certainly have a lot of Jews coming, which is great,” Platt says, “but there’s also a big wider net that makes it really exciting.”

Many, if not most, Dear Evan Hansen fans don’t know the story of Leo Frank, but current events have made Parade, which had a brief Broadway run from December 1998 to February 1999, feel newly relevant.

“The Kanye stuff and the banner on the LA Freeway in Los Angeles, all that was happening right during City Center, so that was the first kick in the pants of like ‘this is very urgent,’” said Platt. And just when the joy of the process, and the jump to Broadway hit its height on the first preview on Feb. 21, Neo-Nazis claiming Frank was a pedophile, amassed outside the theater to hand out flyers.

The protesters haven’t returned — even with the promise of more publicity on opening night. Platt says he is more focused on how the show is affecting audiences than those shouting bile near the stage door.

Most historians believe Leo Frank was innocent, despite a prolific effort by antisemites to prove his guilt. But part of what Platt finds so appealing in the role is how it resists the temptation to make him a perfect victim.

“My favorite part about it is playing a character, both in how he’s described in real life and how he’s written in the show, that is very flawed, and can be headstrong and not a great listener to his wife and very condescending — has a lot of qualities that aren’t perfect and still assert that this person deserves justice and due process and isn’t a monster,” Platt says.

Platt hopes to move attention away from Frank as a symbol or martyr, and focus on playing him as “a guy.”

“I think that’s where the power in the show and also in the history that it comes from is that, regardless of our background, where we come from and what minority we’re a part of, it’s the same system that is, for lack of a better term, f—ing us.”

Since the play started, Platt has connected the antisemitism and racism baked into Frank’s story with rhetoric against the trans community.

“It’s just clear as day the trope that keeps reemerging, the scapegoating and it’s just horrific to see,” said Platt. “These are just human beings trying to live their lives and there are so many more important things to be focusing on that are actually harmful. We’ve seen it before in our community, in the Black community.” White supremacy comes for everyone at one time or another, Platt says.

Platt is the first Jew to play Frank on Broadway (Brent Carver originated the role) and this is the first production of Parade where both Leo and Lucille are being played by Jews. This, he says, is an instance where casting matters.

“I think with all the conversations we’ve had now about authentic storytelling and in this day and age, this story that is so specifically about Jewish oppression and antisemitism and it’s intrinsic to the lines and characterization, it feels like absolutely they should be Jews,” Platt said. But for other roles and material, he’s less stringent. It’s a “case by case” issue, he says.

In some of the show’s most powerful moments, Jewish ritual asserts itself. Lucille lights shabbat candles at the start of Act II. Before Frank is hanged, he sings the shema. While he’s never been quiet about his Jewishness, Platt sees the role as a turning point in his career, where he can follow his passions and work on personally meaningful projects.

On the way to the elevator, a docent stops Platt. She tells him she loves listening to the cast album for Dear Evan Hansen, but she wants to speak with him about something he said in a TV interview about his Star of David necklace, and why he wears it. Platt fishes it out of his shirt and she shows him a watch chain she has on. Her mother wore it, wrapped in rags, in the Kovno Ghetto.

After riding the elevator down, they pose for a selfie. Then, he is out the door for a 7 p.m. curtain. Platt says he feels “galvanized” after his visit.

“What you go through each given day as a person informs the performance and makes it slightly different,” Platt says. “I love the ways that it continues to kaleidoscope all the time. Certainly this will change the way I perform the show tonight, and maybe tomorrow. Just one at a time.”