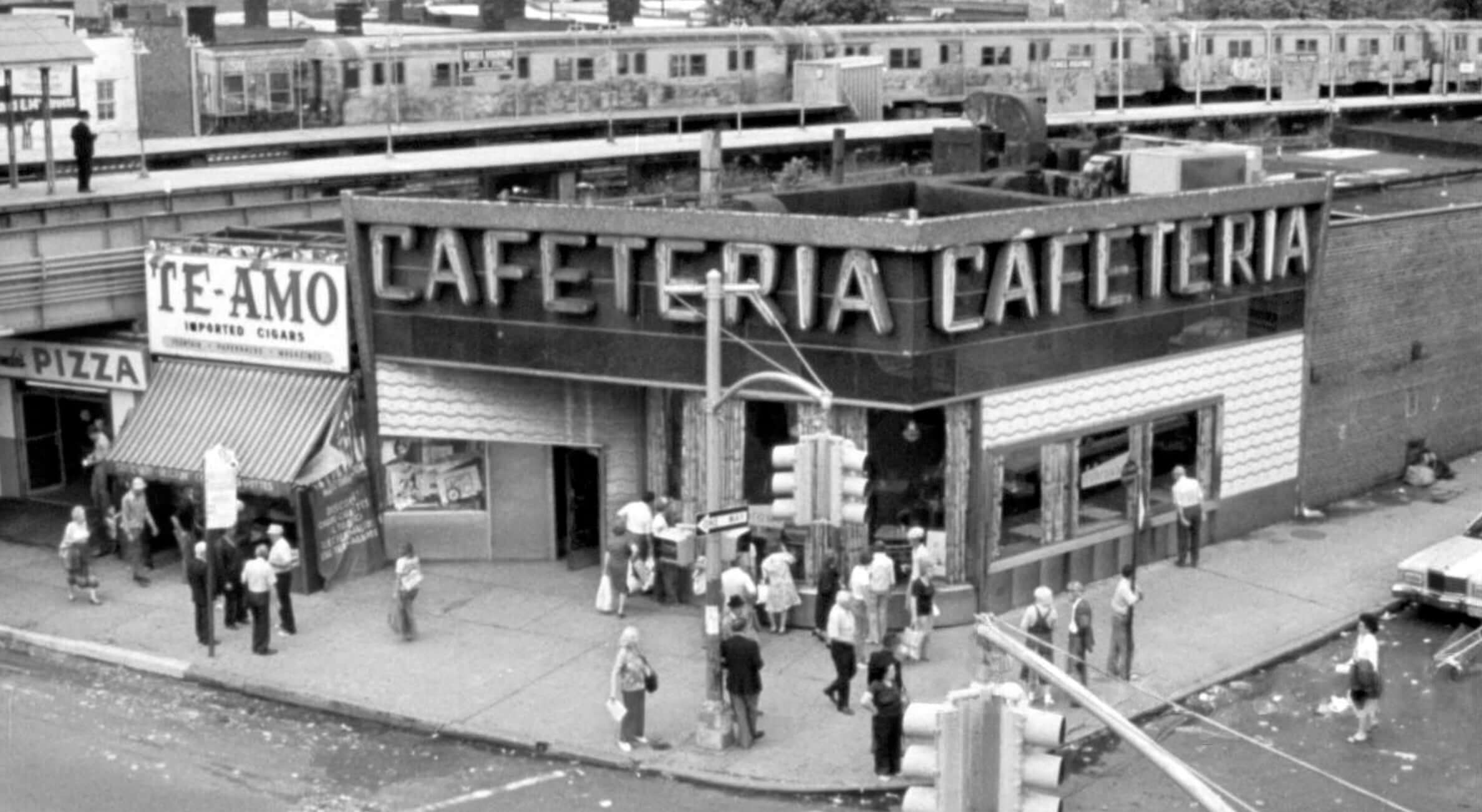

When we all met at Dubrow’s Cafeteria

Photographer Marcia Bricker Halperin reflects on the Jewish diner that shaped her as a Brooklynite and launched her artistic career

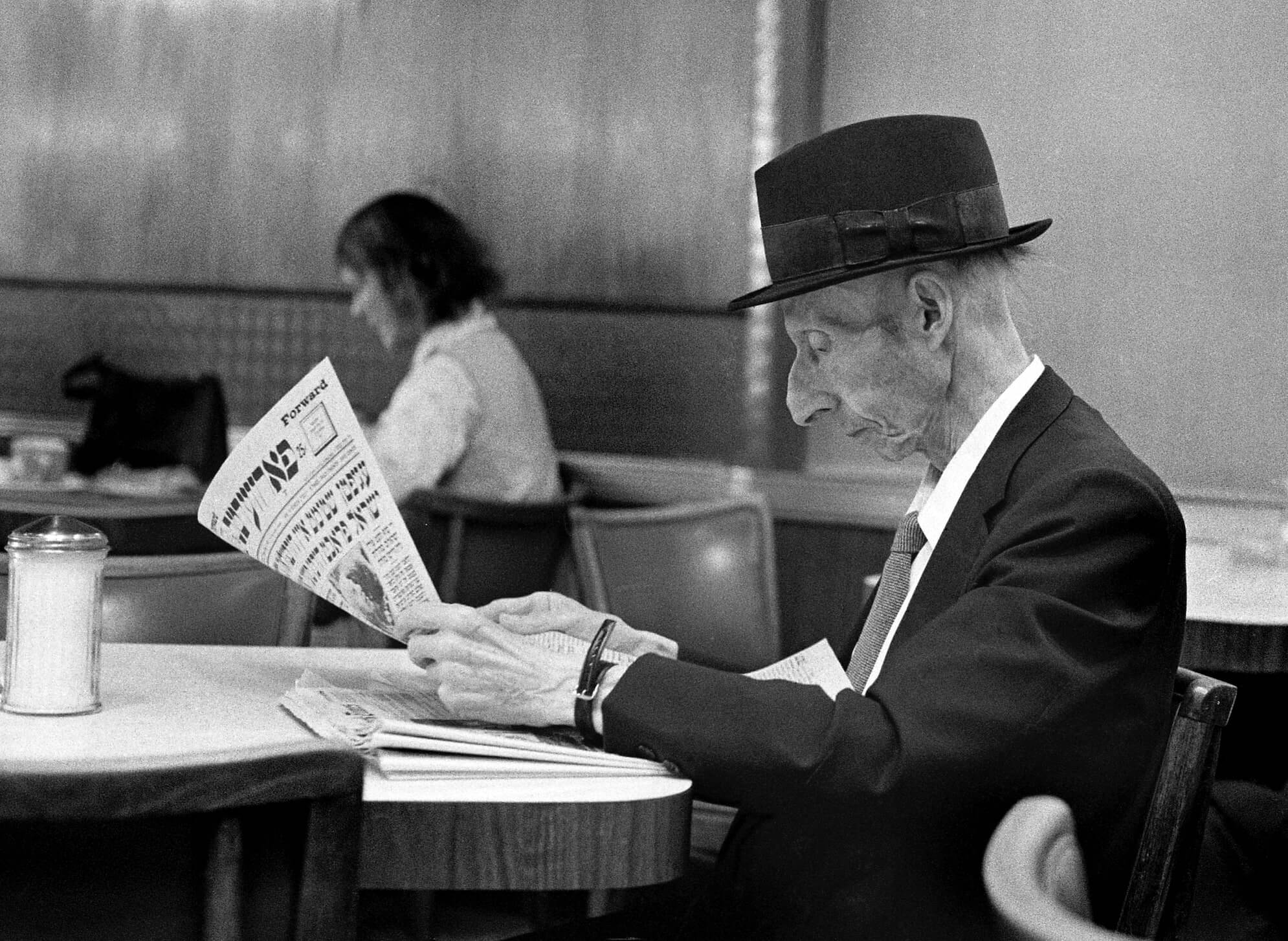

“Sunday Afternoon,” 1975 Photo by Marcia Bricker Halperin

Editor’s note: This essay is an excerpt from Marcia Bricker Halperin’s book of photographs, Kibbitz and Nosh: When We All Met At Dubrow’s Cafeteria, available May 15 from Cornell University Press.

In 1974, after graduating as an art major from Brooklyn College, I was compiling a photography portfolio for an application to a master of fine arts program. I decided I would create a series by photographing store windows on Kings Highway, the thriving shopping thoroughfare that ran through my Flatbush neighborhood in Brooklyn. I was fascinated by the way in which you could capture so many layers through the complicated tones and textures of the glass surface.

The front windows of Dubrow’s Cafeteria on Kings Highway and 16th Street were large and convex, set in a chrome and mosaic facade. The layers in my photographs included diners inside and those standing outside on the street. A long mirror in the interior reflected back yet additional layers. I was attempting to transcend reflection clichés in my work and create a sense of reverie, much like Eugène Atget did when he photographed the shops of Paris in the early twentieth century.

Dubrow’s was an institution in Brooklyn long before I entered it, but I don’t recall going out to eat there while growing up. For the Brickers, the occasional restaurant outing meant having something different, even exotic: Chinese food ordered from columns A, B, or C (lobster sauce), or Italian food—a veal cutlet parmigiana, perhaps. As I grew older, I would not have been pleased to have a date take me to Dubrow’s, as it seemed to be a hangout for senior citizens. By the 1970s, I was much more impressed being taken by car to a twenty-four-hour diner with waiters in Sheepshead Bay, flipping through the selections on a table- side jukebox.

One day in February 1975, while photographing on “The Highway” (as Kings Highway was called), my ungloved, frozen fingers failed to flip the lever to advance the film in my Pentax Spotmatic camera. That’s when I sought refuge through the revolving doors of Dubrow’s Cafeteria. I took a ticket from Mr. Kornblum and found myself, for the first time, in that cavernous space gazing on amazing, unique faces bathed in light from the huge windows and reflected off the wall of mirrors. I was wonderstruck. It was the most idiosyncratic room I had ever seen. My eyes followed the sweeping, amoeba-shaped ceiling half an avenue to the back where it ended at a sparkling mosaic fountain. And it was right in the Flatbush neighborhood where I had grown up. “Go know!”—so went the expression I heard there in the late seventies, accompanied by a slight upward shrug and outstretched hands.

Photographing inside Dubrow’s was not without its challenges. The photographs I created relied on a handheld 35mm camera. Some were made looking down into a boxy, 2 ¼ twin-lens reflex camera. I frequented Dubrow’s on weekday mornings, evenings, and Sunday afternoons, when it was at its most crowded. Many of the initial photographs I made were candids, taken surreptitiously, often including someone I was sharing a table with. The cafeteria management allowed me to sit for hours or to walk around and photograph the counter people, busboys, customers, and food displays. As I became a regular and people engaged me in conversation, the images shifted toward posed portraits. Many of my subjects smiled broadly into the lens in a relaxed way that a male photographer may not have been as likely to capture. Despite the canon of illustrious women photographers I was perceived as a novelty at that time. These photographs became collaborations with my subjects as I sought to stage them within the cafeteria environment and they put consideration into how they would perform for my camera.

Just as diverse as the décor was the lighting within the 45-by-150-foot cafeteria space. Some areas were flooded with natural light in the morning, and evening light was supplied by space-age inspired fixtures. This resulted in highly illuminated sections and pockets of deep shadows. My attempts at using a flash led to some comic situations. As recorded in a journal entry from 1975, after I took a photo using a flash, I overheard a couple at an adjacent table have a heated discussion about whether a light bulb was flickering out or the wife was imagining something. The use of a flash attracted unwanted attention and I was seeking to photograph impromptu interactions. Therefore, the majority of my photographs were made using available light.

In 1976, months after my first visit to the cafeteria, I wrote in my journal, “I was a celebrity at Dubrow’s.” It was a naive but true statement. When I walked into the legendary establishment, patrons waved and gestured for me to join their table. “Take my picture,” they said, and plied me with Danish, cheesecake, or noodle kugel. I carried a large envelope stuffed with imperfect silver gelatin prints to give away, leftovers from hours spent printing in the darkroom. There was a steady supply of these prints as “burning and dodging” were irreversible manual techniques in the darkroom, unlike reversible photo editing in Photoshop.

The process resulting in a finished silver gelatin print began in my family’s apartment under a heavy camp blanket. There, in the pitch dark and by feel, I popped open the film canister with a can opener and loaded the delicate strip of emulsion-covered plastic onto a reel, gently crimping the sprocket edges. Once the film had been placed in a light-tight canister I developed it in the kitchen sink, coordinating with my family’s evening domesticities so as not to disrupt dishwashing. After a three-step chemical process I could finally open the canister and hang the ghostly strip of negatives to dry from a clothespin on a line in the bathroom.

The next day I cut the dry negatives into six frame strips, slid them into glassine sleeves, and then rode over to the Brooklyn College photo lab on my three-speed Royce Union bicycle to make thumbnail contact sheets and prints. This was my technique from 1975 through 1977. In late 1977, when I was hired by the CETA Artists Project of New York City, a federally funded program akin to the WPA, I was able to move into my own apartment and set up a dedicated darkroom. I became a working photographer, an opportunity that was transformative to my development as an artist.

I met amazing people at Dubrow’s. Most were people I ordinarily would never have had a conversation with over a cup of coffee—ex-vaudeville per- formers, taxi drivers, Holocaust survivors, ex-prizefighters, and bookies. Women named Gertrude, Rose, and Lillian all had sad love stories to tell and big hearts.

Conversation flowed freely at Dubrow’s, and it was not unusual for patrons to walk around and greet friends at various tables as if they were at a large private party. For me it was also a “penny university.” In my journal I noted discussions about the 1950s career of Eddie Fisher and guessing games about the age and profession of various habitués of the cafeteria. John F. Kennedy’s campaign visit to Dubrow’s in 1960 was still reflected on often, over fifteen years later. I was told that the staff of Dubrow’s collected buckets of women’s pointy slip-on shoes that were left behind by the throngs that filled Kings Highway that night—throngs that included my father.

I believe I sensed it was a vanishing world on its last legs, and that impelled me to document it. I remember that, during the day, if someone wasn’t nursing a Danish and a twenty-five-cent cup of coffee for hours, the joke was, “Mind my seat, I have to go home to eat.” On many visits the tables were empty, sans a painterly still life of condiment bottles and jars in the morning light. I also perceived cafeterias as places that embodied a secular Jewish culture, something that was of great interest to me. In 1977 I attended a lecture by Isaac Bashevis Singer, who was billed as an “Outstanding Anglo-Yiddish” author, at the Brooklyn Jewish Center on Eastern Parkway in Crown Heights. I adored his short stories, many of which were set in cafeterias, and I regret never finding the nerve that day to tell him about my own cafeterianiks.

When the Dubrow’s on Kings Highway closed in 1978 I continued to photo- graph other last witnesses to these vanishing special places at the Dubrow’s in the Manhattan Garment District, the Horn & Hardart on 57th Street, and the Paradise Cafeteria on 23rd Street and Sixth Avenue. I found the clientele at the Manhattan Dubrow’s to be mostly garment industry workers and transient midtown shoppers. Although that Dubrow’s location had appealing futuristic décor features and a large mural right out of a Hollywood set, complete with fashion models and Greek goddesses, it never became a community space for me until the final closing hours in 1985. On that night a small group gathered for an impromptu farewell party where we quietly pocketed trays and spoons and with commensality ate our last piece of creamy nesselrode pie.

Dubrow’s was the type of place where the genders were referred to as guys and dolls, and I was enamored of that Runyonesque atmosphere. Gossip, lipstick, powder puffs, cigars, kerchiefs, fedoras, leopard pattern coats—all the cafeteria denizens’ accoutrements for dining on gefilte fish, kasha varnishkes, rice pudding, or blintzes. Perhaps the splendid and opulent visual elements of the interior served to counter the isolation, depression, and, sometimes, the poverty of its older customers, who came up through the anxieties of the Depression and World War II.

Older Ashkenazic Jews, who liked to tell me nostalgic stories of hardship, could eat reimagined Eastern European Jewish foods at cafeterias. The noodle kugel at Dubrow’s was chock full of dairy—flaunting cottage cheese, cream cheese, sour cream, milk, and butter—and was topped with a sweet red fruit sauce. This was not an Old World kugel but a showcase of New World abundance. The pastoral mural, with its images of bountifulness on a baroque scale, and the plastic flowers that adorned displays of food choices may have served to counter, for a time, these feelings as well.

The civil rights of smokers were well-supported at Dubrow’s, from the cigarette machine by the entryway to the ubiquitous table ashtrays. Mornings appeared more atmospheric as light filtered through a cloud of cigarette smoke that hung over the room. In more than one of my photographs a stray rectangular line on the edge of the frame turned out not to be a deep scratch on the negative but a cigar edging into the picture. I clipped and saved a 1996 New York Times opinion piece in which the playwright Wendy Wasserstein lamented the presence of big box stores and fast food restaurants throughout New York City. She ended her short essay by writing, “You would never meet Nathan Detroit at a Starbucks counter.”

Whenever I’ve traveled, I check to see if there is a cafeteria still in existence in that city. Over the years, I’ve dined at the Zodiak Cafeteria in Warsaw, the Concord Cafeteria in Miami Beach, Clifton’s in Los Angeles, the Piccadilly in Savannah, and a Horn & Hardart Automat in Philadelphia, among others. All shuttered now. Sometimes I dream about traveling someplace and discovering a uniquely designed cafeteria, created by an immigrant, that is a gathering place for the last remnants of a working-class social and cultural world.

Reprinted from Kibbitz and Nosh: When We All Met at Dubrow‘s Cafeteria, by Marcia Bricker Halperin. Copyright (c) 2023 by Cornell University. Used by permission of the publisher, Cornell University Press.

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

Now more than ever, American Jews need independent news they can trust, with reporting driven by truth, not ideology. We serve you, not any ideological agenda.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism you rely on. Make a gift today!

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Support our mission to tell the Jewish story fully and fairly.

Most Popular

- 1

Fast Forward Ye debuts ‘Heil Hitler’ music video that includes a sample of a Hitler speech

- 2

Opinion It looks like Israel totally underestimated Trump

- 3

Culture Cardinals are Catholic, not Jewish — so why do they all wear yarmulkes?

- 4

Fast Forward Student suspended for ‘F— the Jews’ video defends himself on antisemitic podcast

In Case You Missed It

-

Culture Should Diaspora Jews be buried in Israel? A rabbi responds

-

Fast Forward In first Sunday address, Pope Leo XIV calls for ceasefire in Gaza, release of hostages

-

Fast Forward Huckabee denies rift between Netanyahu and Trump as US actions in Middle East appear to leave out Israel

-

Fast Forward Federal security grants to synagogues are resuming after two-month Trump freeze

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.