Jewish refugees stranded in Hollywood, and 4 other books you need to know this month

Plus, an author’s case for a standing cocktail hour

Photo by iStock

This is Books Briefing, your monthly tour of the Jewish literary landscape. I’m a culture writer at the Forward, and I spend lots of time combing through new releases so you can read the best books out there. You can shop this newsletter by visiting the Forward’s Bookshop storefront. (If you shop from our page, the Forward will earn a small commission.)

My conversation with Cathleen Schine ended the best way a conversation can end: with a spate of book recommendations. The self-described “major-minor novelist” likes to read and do research in bed, but her work situation was compromised by the acquisition of a pandemic puppy, Ruthie, who enjoys chewing her books. Schine spoke with me over Zoom from her study in Venice Beach, California, which was lined with the books that informed her latest novel, Künstlers in Paradise.

The novel follows a family of Austrian Jewish émigrés who arrive in California on the brink of WWII, and are forced to make a new life in the movie industry as the country they love descends into fascism. To understand the enclave of Jewish refugees who sought refuge in Hollywood and ultimately reshaped it, Schine read books like The Kindness of Strangers, a memoir by émigré actress Salka Viertel. To get a sense of the setting, she just had to step outside. Unfolding against the windswept expanses of Venice Beach, the Künstlers’ tale of loss and reinvention can make even a grumpy East Coaster like the writer of this newsletter long for the Pacific’s pink sunsets and jacaranda trees.

Schine and I talked about work routines, the benefits of writing with pencil, and the necessity of a standing cocktail hour. You can read our full conversation, and more about Künstlers in Paradise, here.

Tell me a little about your writing routine. I’ve had many different routines, and it really depends on what age I am. With the first book, my process was very particular: I was working as a part-time copy editor at Newsweek, and they had this big lazy Susan; the copy would go around, and you’d grab some pages. But there were hours when nothing was there. And so I would just try not to attract too much notice and write on little scraps of paper. I basically wrote my first novel that way. For the next book, I had little children, so I just wrote whenever I could.

What makes a good workspace for you? My most productive time writing was when my cousin Betsy had a fifth-floor walk-up in the East Village that she couldn’t really afford. I helped her with the rent and used it as an office during the day. Walking up those five flights of stairs was like, I was not going anywhere. Although there was a bed, which meant I could nap, which is another way of not writing.

Did the pandemic change the way you write? I never in my life had any kind of writer’s block. I just sort of did it. I didn’t do it on a regular basis the way some people do, but I did it. During the horrible Trump years, and then with the lockdown, I had trouble working because it was very hard focusing on what seemed unimportant considering everything else that was going on. On the laptop, you write a sentence, you look at it, and you think, This is the worst sentence ever in the history of the world. Erase it. You write another sentence, and then you think, Nope, that’s the worst sentence ever written. Finally I figured out that if I use a pencil, a really bad pencil, and just sit and write in a notebook without thinking too much, it kind of got me going.

What do you do to wind down after a day at work? This is something the pandemic really changed, which is that cocktail hour starts at 4. Which is the perfect time to watch the Mets if you’re in Los Angeles. So the day ends early, and I have my little glass of Jack Daniels, which my grown children tease me about endlessly.

Kantika is — technically — a novel, but it often feels more like a biography or an oral history. That’s because Elizabeth Graver, known for ruminative novels like The End of the Point, based the book on the life of her grandmother, whose pictures appear at the beginning of each chapter and whose name, like the protagonist, is Rebecca Cohen.

Born in 1907 to a Sephardic merchant family rooted for generations in Istanbul (then Constantinople), Rebecca enjoys a childhood of walled gardens and island holidays; she learns to pepper her Ladino with French phrases, keep kosher and tend to her younger brothers and sisters, activities intended to mold her into a proper Jewish wife and mother. That steady life crumbles at the end of WWI, when the family decides to flee the collapsing Ottoman empire. Their departure from home is the first of many migrations: First to Barcelona, then Cuba and finally New York, where Rebecca submits to an arranged marriage in order to get her family out of Europe.

Graver, who recorded hours of her real-life grandmother’s recollections, straddles the line between reporting and fictionalizing: Even as she imagines Rebecca’s interior life and spins up family dialogues, the author maintains a certain emotional distance, scrutinizing her ancestors’ behavior and motivations with a critic’s sharp eye. Rebecca’s father Alberto, for example, appears not just as a doting patriarch but a spendthrift who runs through the family fortune and collapses emotionally when he has to start over in Barcelona.

Rebecca has to become tough and cunning enough to lead the family, but she’s not always a paragon of virtue. After a failed first marriage to a man whose injuries in WWI left him permanently handicapped, she becomes obsessed with health to the point of cruelty: She almost ditches her second husband when she suspects (erroneously) that he has concealed a heart condition from her, and finds it difficult to muster the kindness and patience necessary to parent a stepdaughter with cerebral palsy. Writing with such candor, especially about a revered family member, is a feat — and the result is a lush but unsentimental drama that emphasizes the Holocaust’s psychological toll on a family that escaped the worst of its horrors.

Pretty much every week between my bat mitzvah and the invention of streaming, I ordered a romantic comedy from my carefully curated Netflix queue, popped it into the pink portable DVD player I received to commemorate my admission into the community of Jewish adults and surreptitiously watched Jennifer Lopez or Katherine Heigl find happiness while my parents thought I was reading Great Books. There’s a unique pleasure in watching two perfect people overcome negligible obstacles in order to be together, and Curtis Sittenfeld’s Romantic Comedy hews to the best conventions of the genre for which it is named. From unexpected meet-cute to crucial misunderstanding to viscerally satisfying post-mortem analysis of every interaction once the happy couple has sealed the deal, the novel delivers the same endorphin rush I learned to crave as a teenager, plus a pandemic and minus the ambient body-shaming that made the 2010s such a joy to live through.

Sittenfeld, who grew up in an interfaith household in Ohio, gives us a heroine fit for the jaded 2020s: Sally, a comedy writer of rare intellect and average looks who works for a Saturday Night Live-esque sketch show. As in the real SNL, Sally is surrounded by schlubby male colleagues who manage to marry stunning movie stars. (Her work bestie is a mashup of Colin Jost and Pete Davidson). Of course, once Sally writes a sketch to lampoon this mating pattern, the laws of the rom-com universe require the show’s hot musical guest to fall in love with her. I knew from the second I opened this book that Sally would marry her pop star and move into his haute minimalist Los Angeles mansion, but I still found myself speeding through the novel to see how this non-star-crossed couple would overcome their extremely minor flaws for the sake of the relationship.

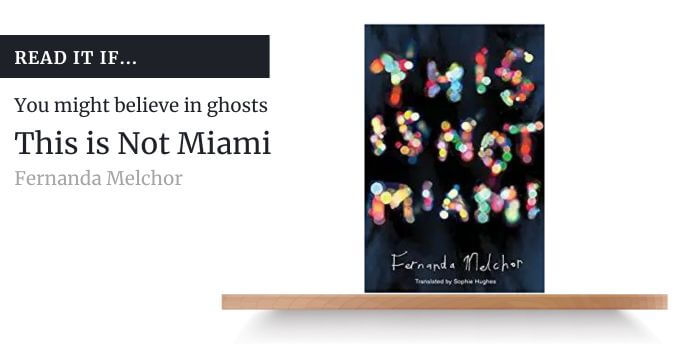

Fernanda Melchor’s uncompromising novels, Hurricane Season and Paradais, chronicle violence and machismo on the margins of Mexican society. Her new collection of essays, This is Not Miami, showcases the reporting that undergirds those books. Melchor, whose German Jewish ancestors fled to Mexico in the 1930s and 1940s, labels these pieces, neither fact nor fiction, as crónicas, a word which might be loosely translated into English as “accounts.” Lacking dates and corroborating evidence, the pieces could never be published in a newspaper, yet they’re all based on stories told by sources in her home city of Veracruz.

The longest and perhaps most compelling piece is a ghost story told by Melchor’s husband about a teenage visit to an abandoned and supposedly haunted mansion on the city’s outskirts. While his friends think the house is a glamorous place to party, one of them becomes “possessed,” forcing the gang to search the surrounding neighborhoods for an exorcist who can save her. Even as Melchor is willing to entertain the existence of supernatural creatures, she keeps her vision trained on the government corruption and cartel violence that underlie so many of the fantasies she describes. In the opening essay, she recalls her childhood conviction that she could see UFOs from her house, and her eventual realization that the lights flashing over the water were actually planes ferrying drugs across borders. “I don’t look for aliens anymore,” Melchor concludes. “My heart’s not in it.”

In the opening of her 1958 debut novel The Best Of Everything, reprinted this spring by Penguin Classics, Rona Jaffe describes in panoramic terms the swarms of secretaries emerging from the subway into Midtown’s rush hour scrum. Some wear “five-year-old ankle-strap shoes” and hide their curlers under headscarves. Others arrive more decorously clad in kid gloves, carrying bagged lunches in carefully preserved department store paper bags. “None of them,” Jaffe observes succinctly, “has enough money.”

The bad news is that no paragraph in Jaffe’s now-classic novel is better than this one. The good news is that Jaffe, who went on to write 15 more novels and died in 2005, writes at the breakneck pace of a Sex and the City season finale and with the wry knowingness of a Nora Ephron novel. The novel follows a clique of 20-something secretaries through their occasionally glamorous, more often bruising lives as “career girls” before women’s liberation. There’s Caroline, an elegant and recently jilted Ivy Leaguer; April, a naive horse-girl from Montana whose thirst for romance makes her a target for unscrupulous men; and Barbara, a divorcée and (gasp!) single mother.

Jaffe, who worked as a secretary and interviewed 50 other working women before starting the novel, doesn’t hesitate to write about sexual violence, illegal abortions, and the all-around vileness of male colleagues — all verboten topics in the 1950s. She later recalled that the typists working on her manuscript, too impatient to wait until she actually wrote the next installment, would sometimes call her for updates on their favorite characters. And the book’s instant bestseller status showed how eager female readers were to hear stories like these.

Jaffe’s cast of white, educated, upper-class women was hardly representative of the workforce in 1958, and it certainly doesn’t mirror today’s. Still, it’s by turns enraging and poignant to read this book with post-#MeToo eyes, to appreciate how much women’s lives have changed in the intervening decades and what’s at stake when our hard-won rights to workplace equality and abortion care are threatened. After you finish, watch the 1959 movie adaptation starring Joan Crawford, if only to compare its overly rosy ending with the book’s sexier and more equivocal one.