How one newspaper column saved lives, reunited families and changed the course of Jewish history

During the Holocaust and its aftermath, the Forward’s Seeking Relatives helped thousands when no one else could

Graphic by Matthew Litman

Research and translations by Chana Pollack, photo illustrations by Matthew Litman

Steven Metzler is 98 and his memory is fading, but he still remembers the details of his escape from the Nazis. It was a stormy night in April 1945. He slipped away from a death march that began three months earlier in Auschwitz, where he had been imprisoned for six months. He crawled beneath barbed wire, crossed irrigation ditches, and found a barn in the Bavarian countryside where he hid in the hayloft.

Luckily, there were chickens. “Boy, did I eat eggs,” Metzler recalled. “And that’s what saved me.”

After eight days in the loft, Metzler spotted an American military Jeep through the barn’s wooden slats. He ran into the open, still wearing his striped prison pajamas, and yelling the few English words he knew.

Among the soldiers was Sgt. Daniel Baron, who knew Yiddish well from having worked at the Streit’s Matzo Factory on the Lower East Side. Metzler told him his story. Baron wept.

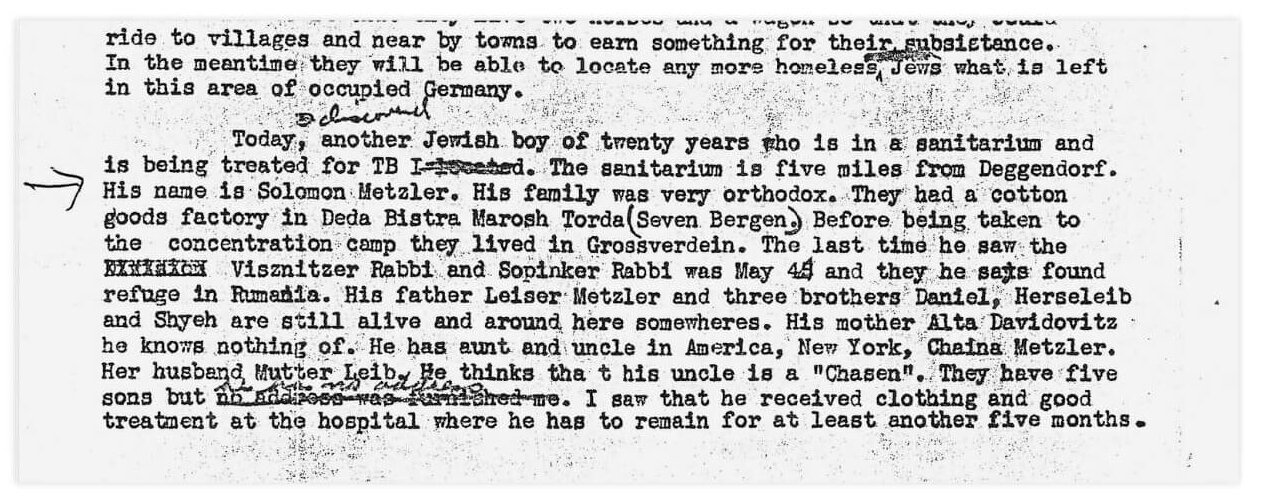

Metzler, who is from Romania, wanted to join the fight against the Nazis, but he was 20 years old, weighed 90 pounds, and had dysentery and tuberculosis. Baron, who was 32, brought him to a German hospital.

“He told the main doctor there, ‘He is a liberated guy from Auschwitz and I want you to make him healthy,’” recalled Metzler. “And he told them, ‘I’ll be back. And if he is not alive, you are dead.’”

Sgt. Baron did come back. And on one of his visits, he wrote a letter home, asking friends to help find the families of Metzler and three other survivors. The letter was shared with the editors of the Forward, which in those days ran lists of such queries in a column called Kroyvim Gezucht — Yiddish for “Seeking Relatives.” The letter was dated July 16, 1945, and asked for help finding Metzler’s aunt and uncle in New York.

Metzler’s Aunt Helen lived in Queens. Her husband, Nathan Zeichner, was a cantor at Congregation Beth-El of Astoria. They had five sons.

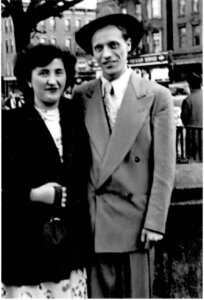

By 1950, Metzler had joined them in Astoria with his wife, Ruth, another survivor he met in Germany. The couple later settled in Colorado — the Rockies reminded him of the Carpathian Mountains of his youth — where Metzler worked as a radio and television repairman, then as a real estate developer.

It was a friend of the cantor’s who saw the Forward listing that changed his life.

“He showed it to my uncle,” Metzler said. “That’s how it started.”

Where people’s futures hung in the balance

From its founding in 1897, the Forward helped Jews scattered by pogroms and war find each other. It reunited families separated by the Iron Curtain, and immigrants lost in the melting pot.

Some connected through the famed advice column, A Bintel Brief, the name in Yiddish for “A Bundle of Letters.” The newspaper’s feature, Gallery of Missing Husbands, also publicly shamed absentee fathers to return to their estranged families.

By World War I, the family-search inquiries evolved into their own column, Seeking Relatives, which ran until the late 1970s. For decades, the Forward did not charge to publish the items; it was a public service. Thousands of lives were forever changed by the column: individuals rescued, families reunited, borders crossed, history shaped.

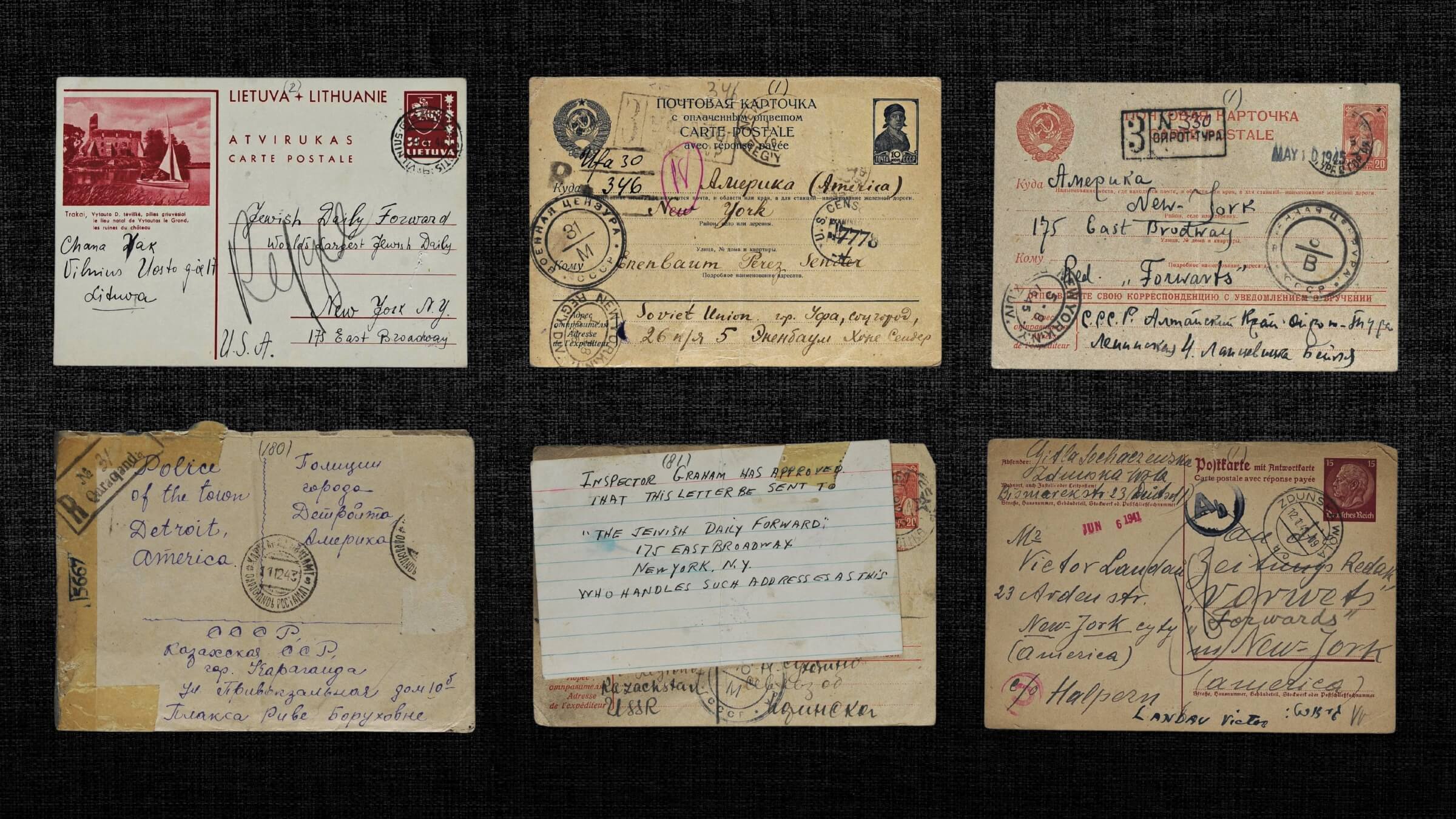

Letters poured into the Forward Building on 175 E. Broadway from every continent except Antarctica. They were written in Yiddish, English, German, French, Polish, Russian, Romanian, Hungarian and Ladino. Some are multi-page outpourings of tremendous suffering, with photos enclosed. Others are the briefest of notes to loved ones.

My own great-grandfather’s cousin — the journalist and exiled Russian Social-Democrat Jeffim Israel — escaped Vichy France with the help of the newspaper. Israel arrived at the dock in New York on Oct. 13, 1940, according to a ship manifest I unearthed. The name that appears on his immigration paperwork as his New York contact is Lazar Fogelman, who began working at the Forward in 1927; Fogelman and my family came from the same shtetl of Nesvizh, Belarus. His father founded the cheder. My great-grandfather was a teacher.

Jared Kushner’s great-grandfather, Naum Kushner, appeared in Seeking Relatives in May 1946. He was looking for someone named David Bussel. Three years later, David Bussel’s son Harry, a doctor, sponsored Naum and other Kushners — including the future first son-in-law’s grandparents Joseph and Rae — to come to the U.S.

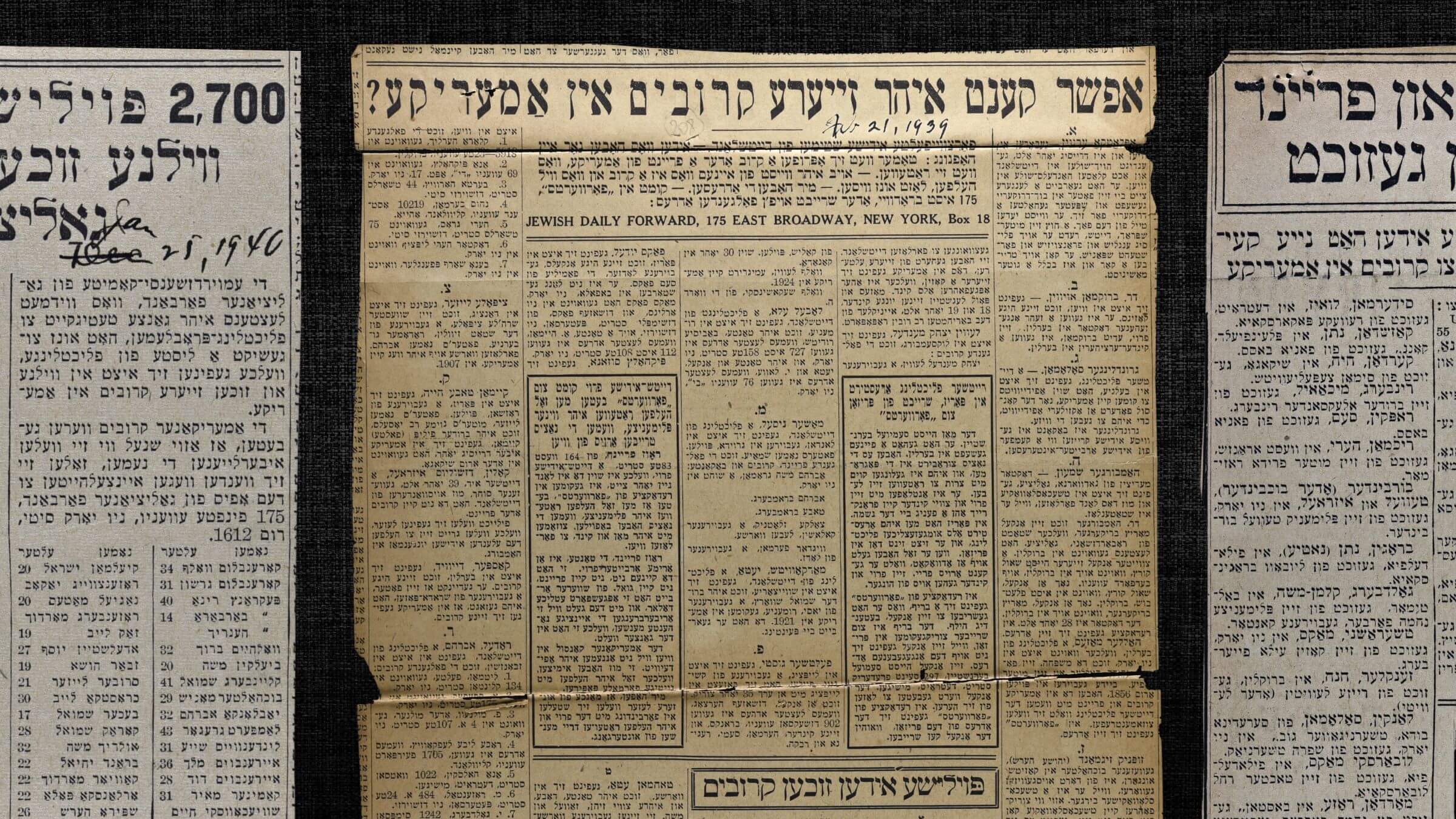

Sometimes, the column showcased a single person. During the Holocaust, it swelled with lists of names and basic information, like these, from Nov. 12, 1945:

- Shmul Silverberg, husband of Malke Silverberg (Sokosky) survived alone and is currently located in Belsen. He seeks his cousin Aaron Blum of New York. (Urgent. Respond via cable)

- Rozika Nay, currently located in Sweden, seeks her sister Loyrka Nay of Cleveland, Ohio.

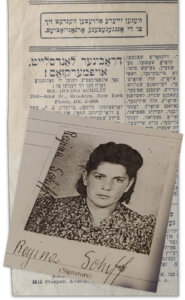

- Warshawsky Heyman. Brooklyn, N.Y. owner of a dry cleaning store, and Louis Schiff, both of Drobin, Poland are sought by their niece Regina Schiff, around 22-years-old, a sole survivor currently located in Germany.

Regina Schiff, like Steven Metzler, survived Auschwitz and, upon liberation, met a Jewish American soldier, Irving Schilit, who wrote to Seeking Relatives when he returned from Germany.

Six months later, Regina came to New York to live with an uncle, aunt and two cousins. She stayed with them for two years on the Upper West Side, then got married. One of those cousins would later become the mother of Lynn Harris, founder and CEO of Gold Comedy, who — poetically — was co-host of the Forward’s Bintel Brief Jewish advice podcast. Harris had never seen the Seeking Relatives listing, though her mom, who died in 2020, had told her “that Regina somehow put ‘an ad in the newspaper.’”

When Regina’s family was deported from the Drobin Ghetto to Auschwitz on Nov. 21, 1942, Harris explained, “the adults made all the children memorize the names of Regina’s father’s siblings in America and commanded and begged them to search for the American family if left alone after the war.” Regina was the only one of her extended family to survive.

Chana Pollack, the Forward’s archivist, went hunting for Regina’s ad through the website of the National Library of Israel, which has digitized archives of the Forward. It was a long shot — the faded letters can be hard to read, issues are often missing, and Harris was unsure of Regina’s Yiddish name. Chana found it after a couple of weeks.

“This is a family holy grail,” Harris said when she received the ad via email. “I just wish my mom could have seen it.”

‘Every ghastly story he receives can be found in his desk drawer’

Chana receives requests like Harris’ regularly from Forward readers researching their family histories, but rarely has enough time to help them. That’s why the Forward is hoping to translate and digitize the Seeking Relatives columns and create a database where people could look the ads up themselves. Toward that goal, the International Association of Jewish Genealogical Societies gave us a $3,000 grant last year and Chana worked with the website JewishGen on a pilot project involving around 500 listings.

Meanwhile, Chana and I set out to track down some of the stories behind the column. We wanted to learn about what happened to people reunited via the ads — and to their children and grandchildren. We also wanted to tell the stories of those the column could not help.

We began by looking at scores of columns in the online archives. We also collected published references to Seeking Relatives — in her 2020 memoir I Want You to Know We’re Still Here, for example, Esther Safran Foer, who was born in Poland in 1946 to survivor parents, credits the Forward with connecting her family to American relatives. Esther’s son, Jonathan, is a well-known novelist.

About a week into the project, I discovered that thousands of original, hand-scrawled Seeking Relatives letters sent to the Forward had found their way to the archives of Yad Vashem, the Holocaust memorial and museum in Jerusalem.

Editor’s note: This is an unusual — and unusually long — story for today’s Forward; a multitude of stories, really. You can read it the regular way, from top to bottom. Or you can jump ahead to the profiles, which of course represent only a tiny fraction of the thousands of lives forever changed by Seeking Relatives.

- Stuck in France

- From shtetl to Shanghai

- A desperate mother

- Hidden by nuns

- Soldiers’ stories

- Letter to the rebbe

- A forgotten family

- Aspiring American

- The end of Seeking Relatives

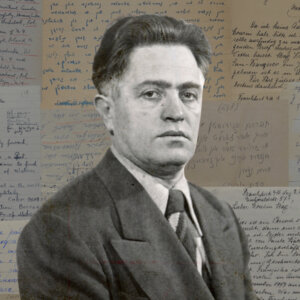

Isaac Metzker, a Yiddish novelist and longtime Forward editor who left Europe in the 1920s, had donated them along with other Holocaust-related clippings and testimonies in 1951. “Every ghastly story he receives can be found in his desk drawer,” our founding editor Ab Cahan wrote of Metzker in 1947.

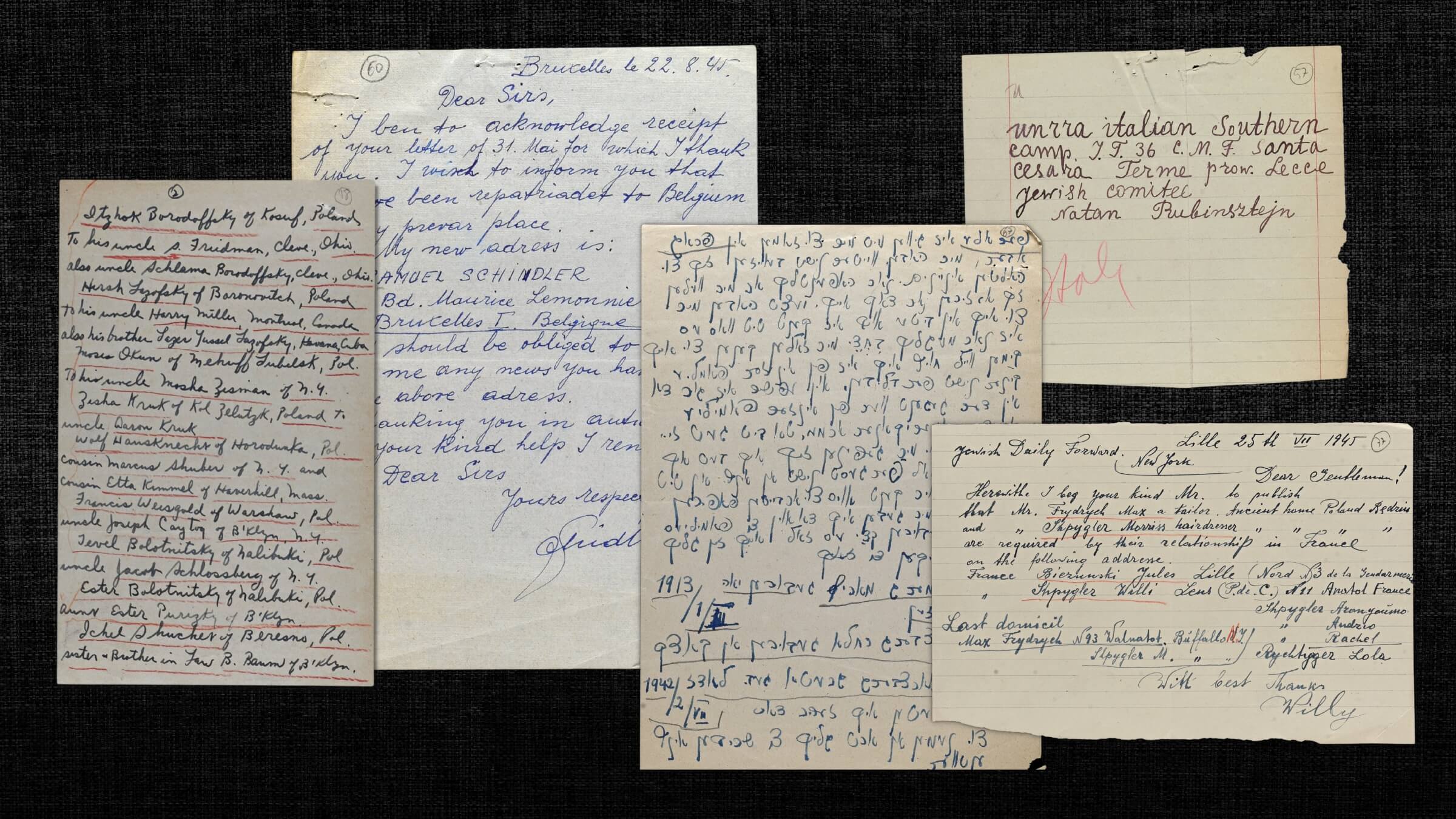

There are pleas from internment camps and appeals from ghettos sent in envelopes with the ominous red Nazi censor stamp of an eagle gripping a swastika, messages scrawled on U.S. Army-issued stationery or on the back of Red Army propaganda.

The files are incomplete. Pages are torn, photos are unlabeled, and some stamps have been clipped out. But Metzker and his editorial assistant, Yetta Frankel, left memos and markings in the margins. It is clear from thank-you notes and messages from aid organizations that many people were indeed connected through the column.

Take Avrom Gross and his cousin, Joseph.

“At the same time as I have word from you, I also received a letter from my relative,” Avrom wrote to the Forward from Brussels on July 26, 1939. “You’ve revived me and I’m a completely different person. From such incredulity, I have no way of thanking you.”

Yad Vashem has digitized much of Metzker’s papers, as well as hundreds of related files donated by the Joint Distribution Committee (also known as “the Joint”). The museum shared 13,000 scanned pages dated from 1938 to 1951.

“No historian has ever touched this,” said Hasia Diner, a professor emerita of American Jewish history at New York University. “It’s a powerful statement about the rebuilding of Jewish communal life for Jewish families in the aftermath of the war.”

‘Who handles such addresses as this’

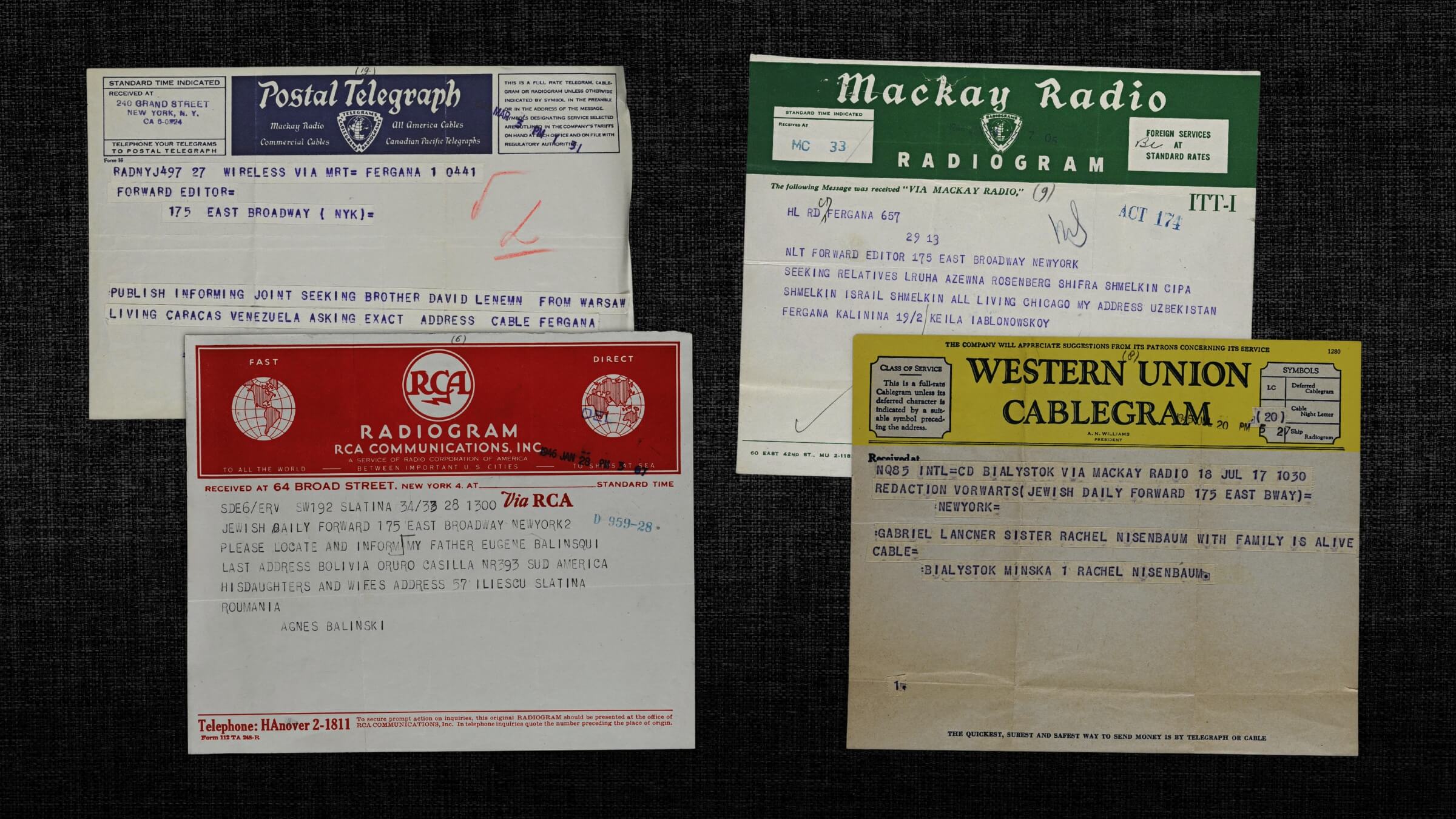

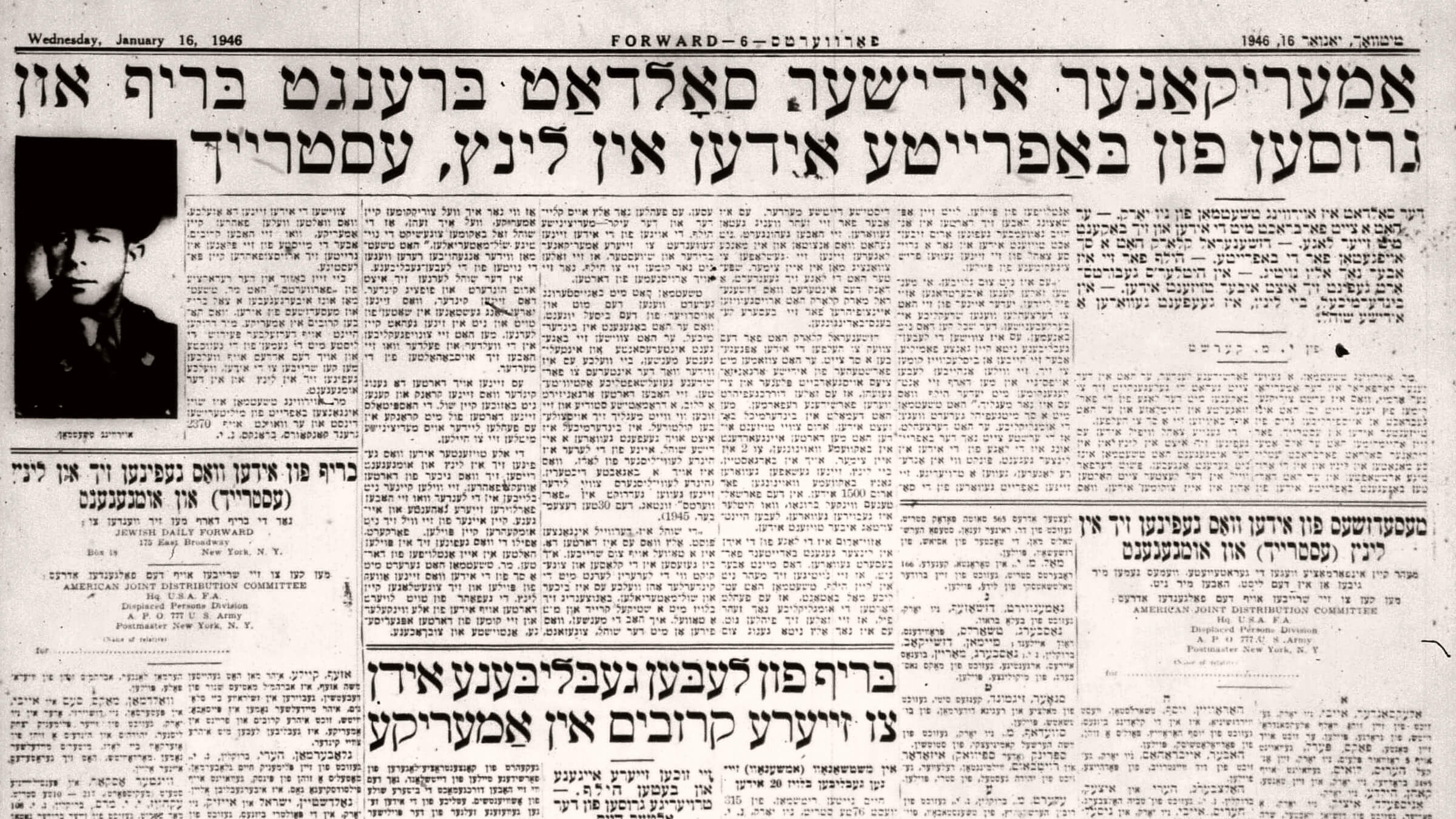

The Forward wasn’t the only newspaper with a column seeking to connect refugees with their relatives during and after World War II. In September 1945, Otto Frank placed an ad seeking his daughters Margot and Anne in the German-language Jewish journal Aufbau. But the Forward was publishing in the native tongue of most of Hitler’s victims and had bureaus and editions in every major Jewish American community. By the end of 1945, hundreds of letters were arriving each week to the paper’s Lower East Side headquarters.

They arrived by the boxful from returning soldiers like Irving Schilit, and from aid organizations like the Joint and the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society.

Sometimes, mail addressed elsewhere made its way to the Forward. A letter from Russia to “The New York Taims” is in the files. So is a 1943 Kazak postcard to “The Bureau of Address,” bearing a note from an U.S. postal inspector to deliver it to the Forward, “who handles such addresses as this.”

Some addressed their envelopes with the newspaper’s tagline, “The World’s Largest Jewish Daily.” That prideful boast had become a weighty responsibility. Copies of the newspaper were passed around displaced persons camps as proof that Jewish life had a next chapter.

“I’ve survived various concentration camps in Germany but have lost my entire family and all my friends,” Beba Epstein from Sweden wrote on July 28, 1945. “I am looking for my uncles, Lasar Epstein and Isaac.” Her letter is now part of an online exhibit at the YIVO Institute of Jewish Research.

In addition to printing the letters, the Forward broadcast some via its radio station WEVD, and coordinated searches with aid groups in the U.S., Europe, Israel and South America.

Lasar Epstein, Beba’s uncle, was a labor activist who worked in the Forward Building. According to testimony Beba gave to UCLA in 1984, a friend heard her plea on the radio in Israel and alerted Laser. She arrived in New York on Sept. 16, 1946.

“I was greeted by my relatives and acquaintances, after so many years of desolation and homelessness,” she wrote in a 1950 essay for the Forward. “Sitting in the taxi driving home, I felt I was indeed going home and wouldn’t need to wander ever again.”

Steven Metzler’s family treasured Sgt. Baron’s letter as an heirloom. His grandson Dan Jacobson, who made a 2008 documentary about Metzler’s Holocaust story, shared it with me.

But the people I tracked down had not seen the letters until I shared them. Descendants of survivors and soldiers alike wept at the discovery.

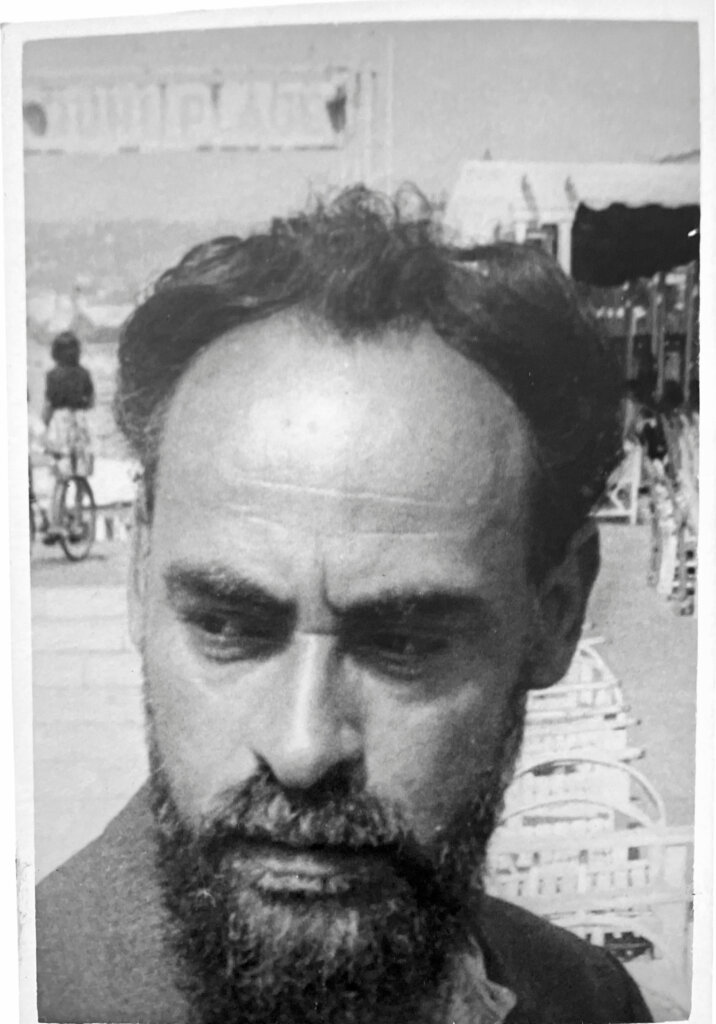

Jason Kliot, an Academy Award-nominated producer, was stunned when I shared what his father, Boris, wrote from Paris after the war in October 1945. Boris, then 22, did not mention the Rumbula Massacre, where the Nazis killed 27,000 Jews — including his parents and sisters — or tell his own story of surviving four concentration camps. Instead, he listed every detail he had about his Aunt Riva.

“She married a man named Schwarz from Philadelphia,” Boris wrote. “She lived sometimes in Miami Beach.”

The Forward shared the letter with the Joint, which helped Kliot emigrate to the U.S. in 1949. He became an entrepreneur selling fashionable eyewear, and then the main donor for a memorial to victims of the 1941 massacre in his hometown.

“The letter put me right there with him,” Jason Kliot told me. “Nothing, not a penny in his pocket, trying to figure out his next move: how to survive, how to get to his dream, how to get to America, how to rebuild his life.”

Each letter is a window into a journey, a deeply personal one. Here are eight of them.

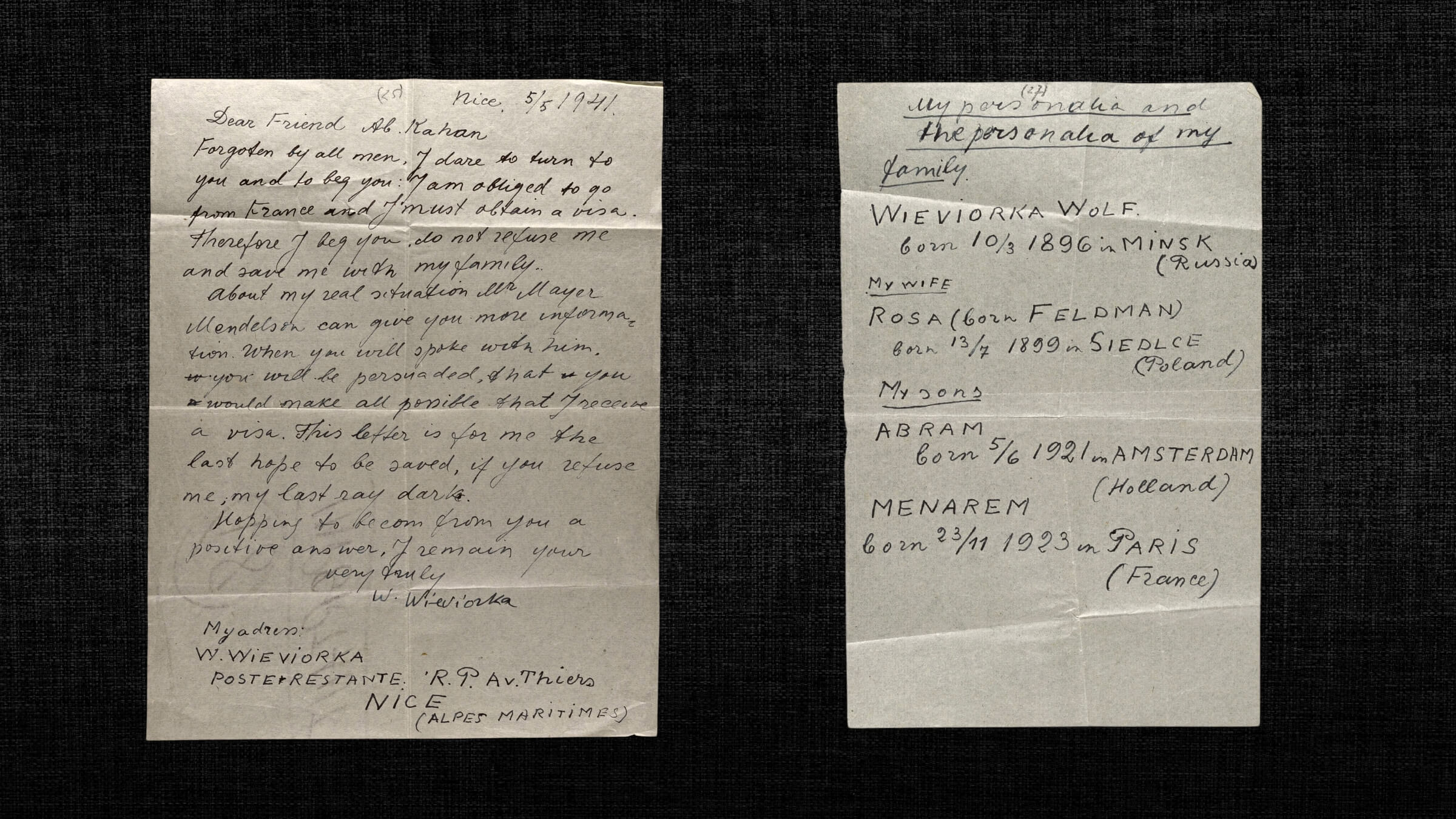

LETTER FROM WOLF WIEVIORKA, MAY 5, 1941

Stuck in France

Wolf Wieviorka, a writer who was born near Warsaw, published short stories in the Forward in the 1930s, and addressed his plea for help directly to the paper’s editor-in-chief, Ab Cahan.

“Dear Friend,” he wrote on May 5, 1941 from Nice, France. “Forgotten by all men, I dare to turn to you and to beg you. This letter is my last hope. If you refuse me, my last ray darkens.”

Wieviorka was 45, had fled Paris after the Nazis took the city, and was begging for assistance in obtaining U.S. visas for himself, his wife and their two teenage sons.

In 1941, immigration quotas limited the number of U.S. visas from France to 3,086. To compete for one of those, the Wieviorkas would have needed an affidavit of financial support.

Wieviorka’s letter to Cahan followed one he wrote the year before to the Jewish Labor Committee, a New York-based group that operated escape networks across Europe. In that letter, written in Yiddish from Toulouse, he played up his Bundist credentials and contributions to the Forward.

“There are only two possibilities for me,” he said. “To travel to America or to disappear.”

This letter jumped out at me because the labor committee is the group that rescued my great-grandfather’s cousin. In her 2021 book Rescue, Relief and Resistance, historian Catherine Collomp said that the group helped about 1,500 Jewish and non-Jewish socialists and labor leaders from France, as well as a large number of Polish Bundists in Lithuania, get out in 1940 and 1941. It obtained emergency visas, paid passages, and even arranged for forged documents and smuggled some refugees.

Wieviorka does not appear on a list of JLC sponsored visa recipients in 1940. “The only thing the JLC could do was to argue name by name in Washington,” Collomp said in an interview, for people “they could vouch for and who were in extreme danger.” The French historian does not know if Wieviorka had gotten in touch with the JLC too late — or if he simply wasn’t granted a US visa. “In the summer of 1940, its first list was composed of prominent anti-fascist and anti-Nazi leaders,” she said.

Wieviorka’s letter to the Forward is marked “Special” in Metzker’s files at Yad Vashem, but they contain no clue about what steps were taken on his behalf.

The JLC was founded by Forward employees and housed in the newspaper’s building. Collomp believes the letter to Cahan was a last-ditch attempt to appeal to the JLC.

Wieviorka and his wife, Rosa, were deported from Nice to Auschwitz in 1943. She died there, and he perished on a death march from the camp in 1945. Their two sons, Menarem and Abram, escaped to Switzerland and survived.

Collomp told me that Jewish Labor Committee records show that the group managed to get the Wieviorkas a visa in late 1941. When I told this to their granddaughter Annette, a French historian of the Holocaust, she shook her head. “He probably never knew he received it,” she said.

Though Annette Wieviorka published a book about her family in September 2022, she was unaware of Wolf’s letter to Cahan, his “friend” at the Forward. She was somewhat surprised by its desperate tone, given that Nice was at the time beyond the reach of the Gestapo.

“In May 1941, there was no Final Solution, there was no deportation,” she noted. “It was like he had a kind of premonition.”

LETTER FROM CHASKIEL & ARON KOHN, JULY 3, 1941

From shtetl to Shanghai

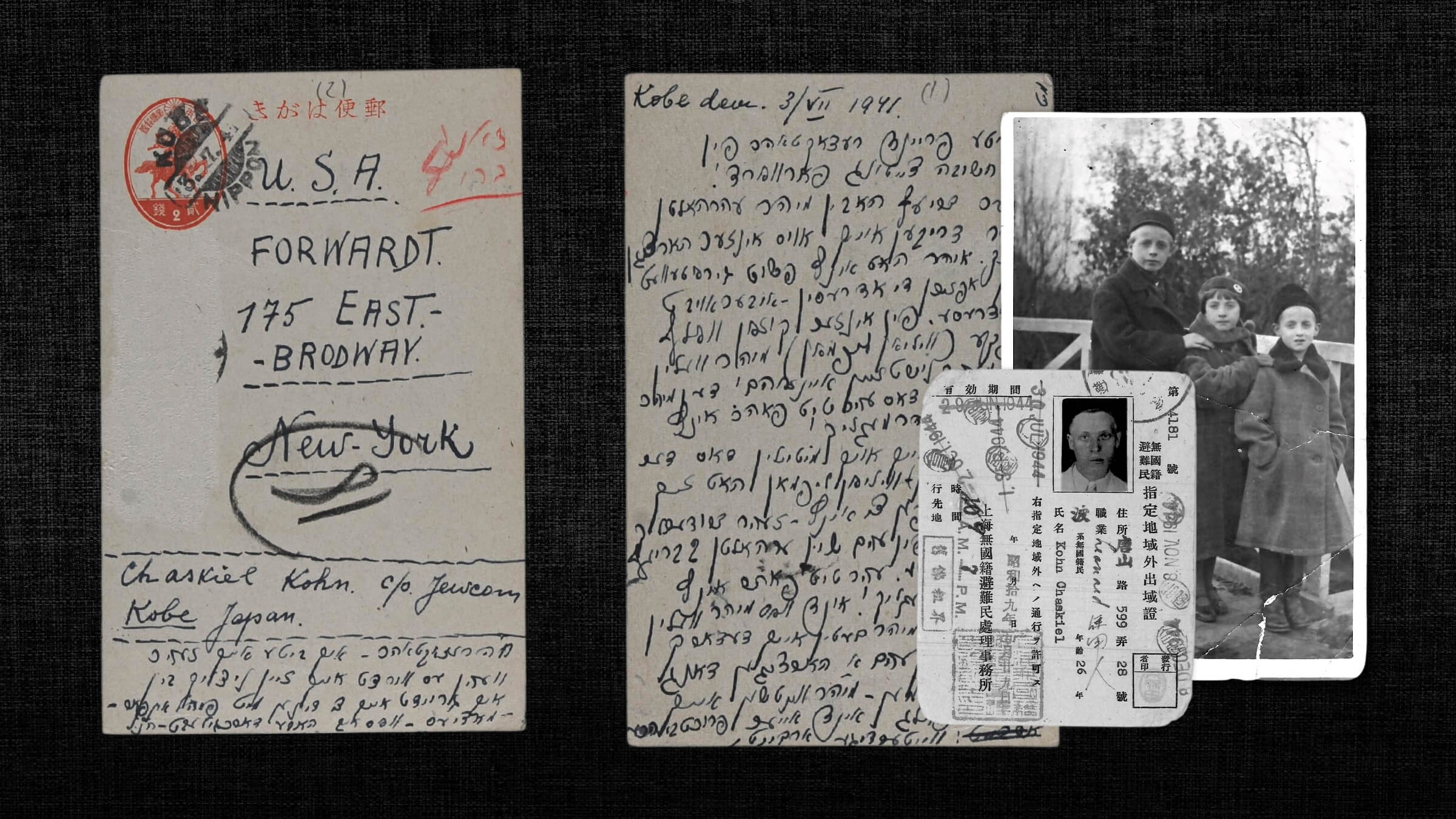

Esteemed Editor Sir, of the influential newspaper Forward! We wish to express our heartfelt thanks. Simply put, you rescued us by finding the addresses — especially the address of our cousin Woolf Lipke (Vilian Lipman). We are no longer bereft! (Chaskiel and Aron Kohn, July 3, 1941)

What’s striking about this postcard is that it bears the stamp of Imperial Japan. Chaskiel and Aron, both born in Rypin, Poland, were among 2,100 European Jews who found refuge from the Nazis in Kobe thanks to Chiune Sugihara, a Japanese diplomat based in Lithuania.

When Germany invaded western Poland in September 1939, hundreds of thousands of Jews fled east. Chaskiel and Aron had the responsibility of accompanying their paternal grandfather, Herschel. “They walked to Warsaw,” explained Chaskiel’s son William, a lawyer who lives in New Jersey. It was a distance of 109 miles. “At that point, their grandfather said to them that he had no more strength to go on, and they should continue.”

The two cousins trekked another 140 miles, crossing into Lithuania. There they encountered Sugihara, later called “the Japanese Schindler” for defiantly issuing 10-day transit visas to thousands of Jews, including the Kohns. The Joint paid for their 6,000-mile ride on the Trans-Siberian Railway and ship tickets for the final leg of the journey to Japan.

In Kobe, the Sugihara Jews had only temporary visas and little opportunity to work. Thousands around the world were in similarly precarious situations, having escaped the reach of Hitler’s army only to land in unexpected places with unclear prospects.

The Forward received communiqués from German Jews held by the British in the Mauritius Islands after being denied entry into Palestine; malnourished families in Soviet camps in Uzbekistan; penniless refugees marooned in Morocco; and Jews who had been evacuated from Gibraltar to Jamaica.

Chaskiel wrote to the Forward on Feb. 26, 1941, describing his situation in Kobe as “catastrophic,” and asking for help in finding “Woolf Lipke” in Cleveland.

Lipke turned out to be William Lipman, a cousin who emigrated to the United States in 1913 — five years before Chaskiel was born. He lived in Cleveland, and had two successful “Bill’s Clothes” stores and political connections.

The Forward ran an ad on April 1, 1941, and again on May 16. Lipman, who was already trying to get his own siblings out of Poland, heard about it through a friend of another émigré from the same town.

On June 23, Chaskiel wrote a letter directly to William; a copy of it is in a family collection in the Western Reserve Historical Society in Cleveland. Within days, according to records in the collection, Lipman sent Chaskiel and Aron money and began helping them apply for both U.S. and Paraguayan visas.

After receiving $30, the equivalent of almost $600 today, Chaskiel wrote to the Forward again on July 3, asking the editors to print a “heartfelt thanks” to Lipman. The next day, the cousins sent a telegram to Lipman, urging him to get visas, ending the message: “Deportation Threatening Helpless.”

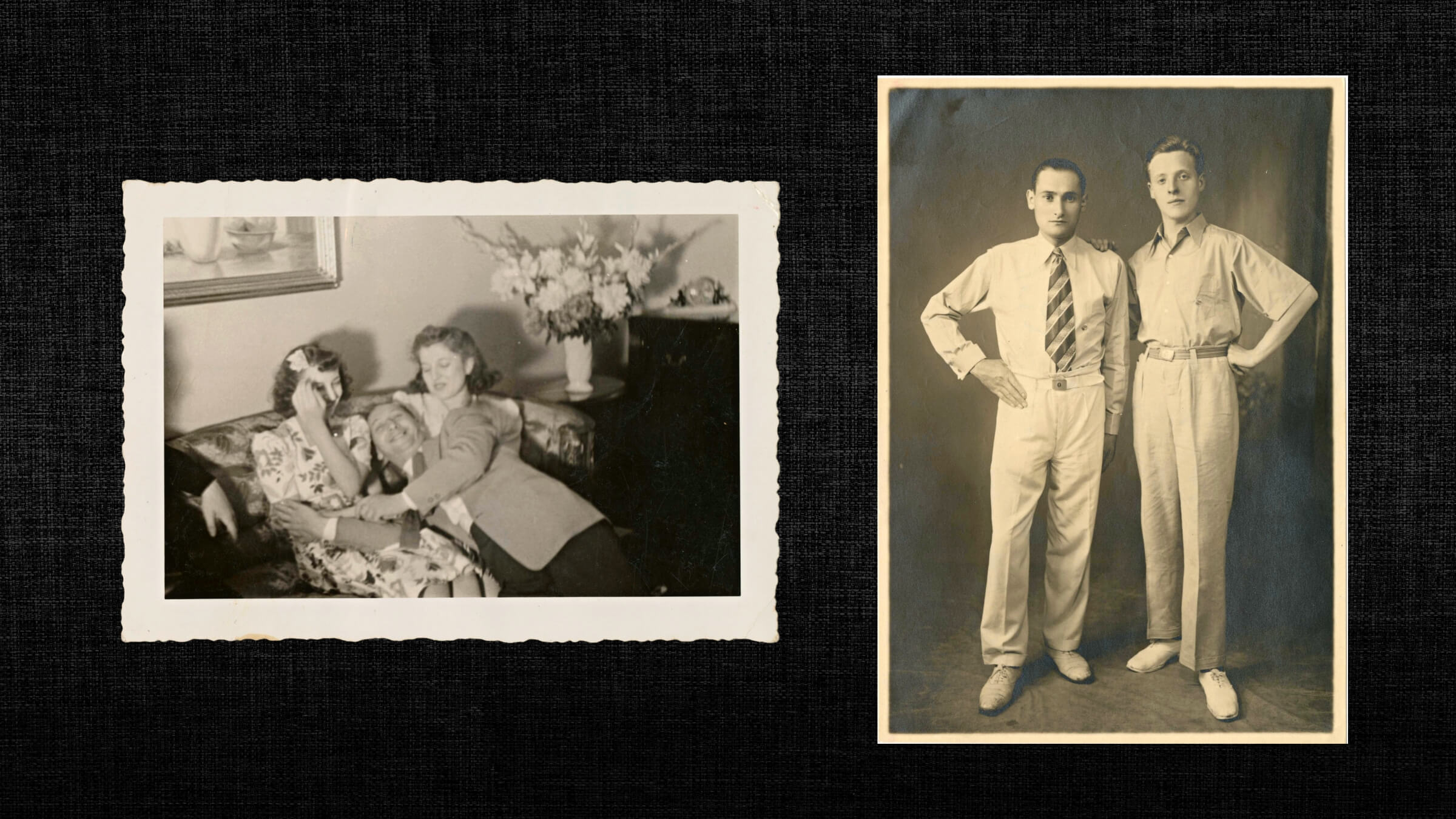

At this point, Lipman and the cousins exchanged photos. Chaskiel and Aron stood side by side, arms akimbo, clean shaven and staring into the camera. Bill’s photo is a candid of him and his wife, Gertrude, at a social gathering in an American living room.

Then on Aug. 30, 1941, Chaskiel wired Lipman to say he and Aron were being moved to Japanese-occupied Shanghai.

According to the 2022 book The History of Shanghai Jews, some 20,000 Jews were packed 10 to a room in Shanghai’s square-mile ghetto, with scarce food. In October 1941, Chaskiel and Aron wrote Lipman a long, heartbreaking letter:

“The streets are full of gruesome images,” they said, “Nobody has an iota of compassion. There is robbery and petty theft, it’s a city, chaotic for anyone who led a comfortable life previously.”

“Don’t abandon us, don’t let us drop into this vortex,” the cousins continued. “We can’t suffer it much longer, we don’t want to endure this Shanghai life. Its problems are too much to bear.”

On Nov. 14, 1941, Lipman notified the cousins by telegram that their paperwork had been transferred from Kobe to the U.S. consulate in Shanghai. But three days later, the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society wrote to inform Lipman that his affidavits of support were no longer valid; he had to start the process anew.

Then, on Dec. 7, the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, and surrounded the Shanghai ghetto with barbed wire. Unemployment soared and charity from abroad plummeted.

In 1942, Lipman received a postcard the cousins had sent months earlier. The penmanship had deteriorated, as if the Yiddish characters themselves had grown more desperate. “We’re frantic,” the cousins wrote. “This is a bleak time for us and we don’t know, God forbid, what tomorrow may bring.”

The correspondence ends there. William Kohn, Chaskiel’s son, said the cousins spent the war years studying Torah with students of the Mir Yeshiva who took the same path as the Kohns through Japan to Shanghai.

In 1946, Lipman welcomed them into his home and offered them jobs in his clothing stores.

But they did not like that the stores were open on Saturdays. “My father said that he didn’t feel that he survived in order not to practice Orthodox Shabbos,” William Kohn explained. So Aron and Chaskiel moved to Brooklyn.

It was only after Lipman’s death in 1981 that his family learned all he had done to help the Kohns — and that only one of his own 12 siblings survived the war.

“At his shiva, these two Hasidic gentlemen from New York walked in,” remembered Lipman’s grandaughter Terry Lipp. “They told us his stories.”

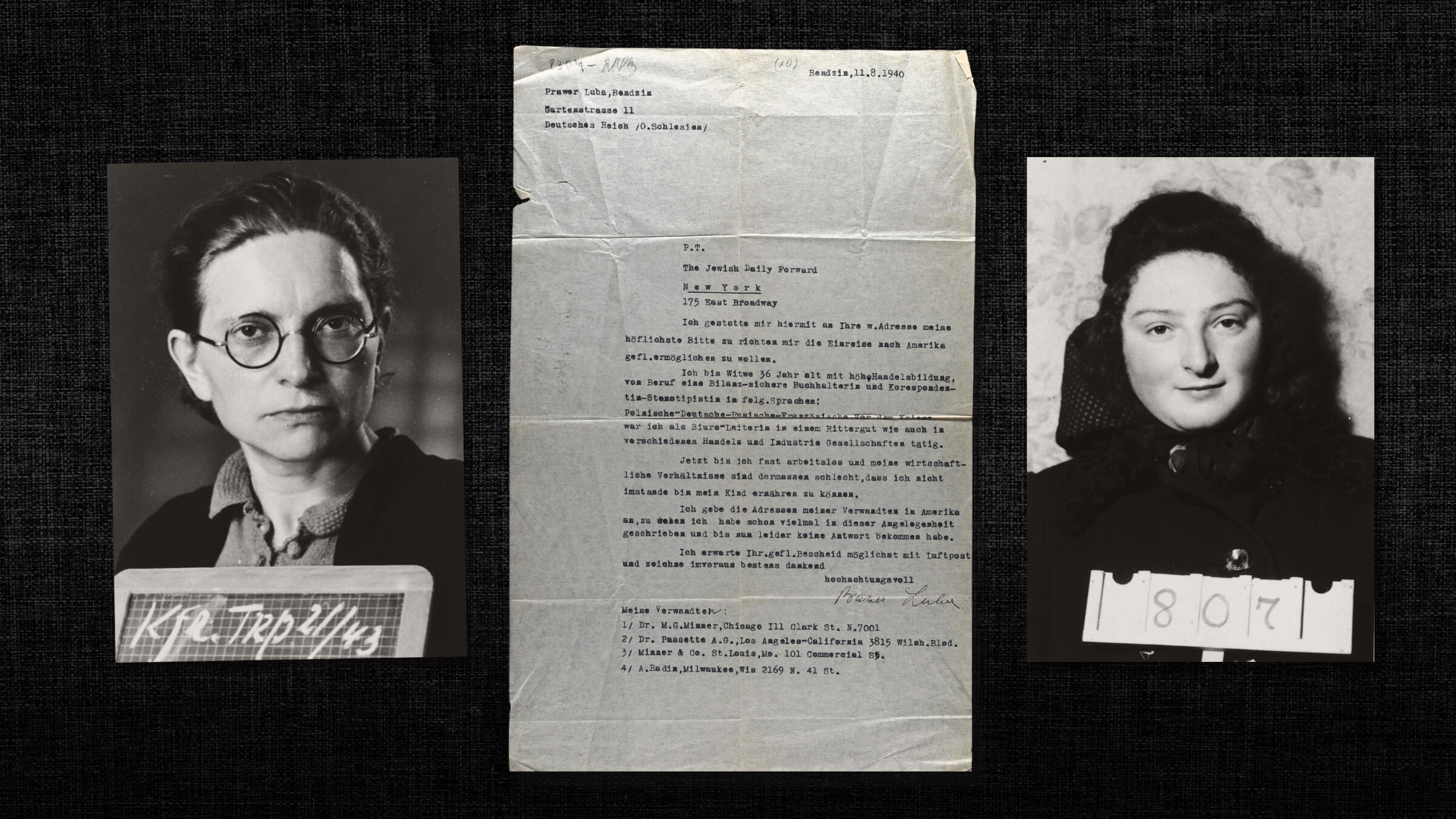

LETTER FROM LUBA PRAWER, NOV. 8, 1940

A desperate mother

I am almost without work and my economic circumstances are so bad that I am unable to provide for my child. (Luba Prawer, Bendzin, Poland, Nov. 8, 1940)

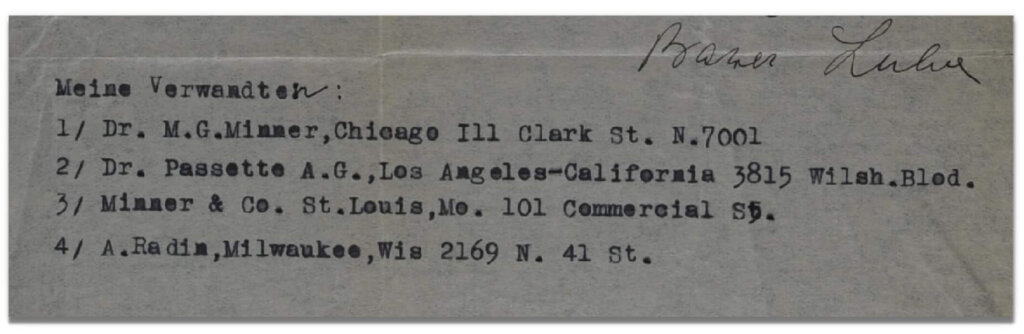

Luba Prawer was a 36-year-old widow when she wrote to the Forward. Born into a prosperous Jewish family, Prawer had become destitute after the Nazis invaded Poland in 1939. She listed the names and addresses of four distant relatives she had probably never met:

The last was A. Radim in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. State death records show that Abraham Radim had been gone for 15 years.

No. 2 on Prawer’s list was “Dr. Passette A.G., Los Angeles-California 3815 Wilsh. Blvd.” There was a dentist named Alvin J. Passette on Wilshire Boulevard, though the building number was off by one digit. Passette’s mother had come to the U.S. in the 1890s. His son Anthony, now 78, did not know until we contacted him that the family still had relatives in Poland during the Holocaust — or that they had reached out for help.

Prawer wrote in hopes of an affidavit for a U.S. visa, and her letter — like many others — reads in part like a resume. She boasts of professional skills and experience as a bookkeeper and stenographer, making the case she would not become a financial burden.

The letter is written in stilted German; Nazi censors did not allow letters in any other language. The envelope bears the Nazi Reichsadler seal and the Ghetto Judenrat stamp.

Prawer and her daughter, Eugenia, did not receive U.S. visas. Luba found a job as an accountant in a shoe workshop, according to a 1999 biography Eugenia submitted to the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum. After graduating from an underground high school in 1941, Eugenia joined her mother in the workshop.

The following year, their employer, Alfred Rossner, saved them and two of their cousins from being deported to Auschwitz. Luba and Eugenia were again put on deportation lists to Auschwitz in 1943, but managed to escape the ghetto. They survived the rest of the war by taking on the identities of non-Jewish Polish forced laborers in Germany.

After the war, they returned to Poland, where Eugenia became a doctor and author, and eventually emigrated to Germany. She died in 2014.

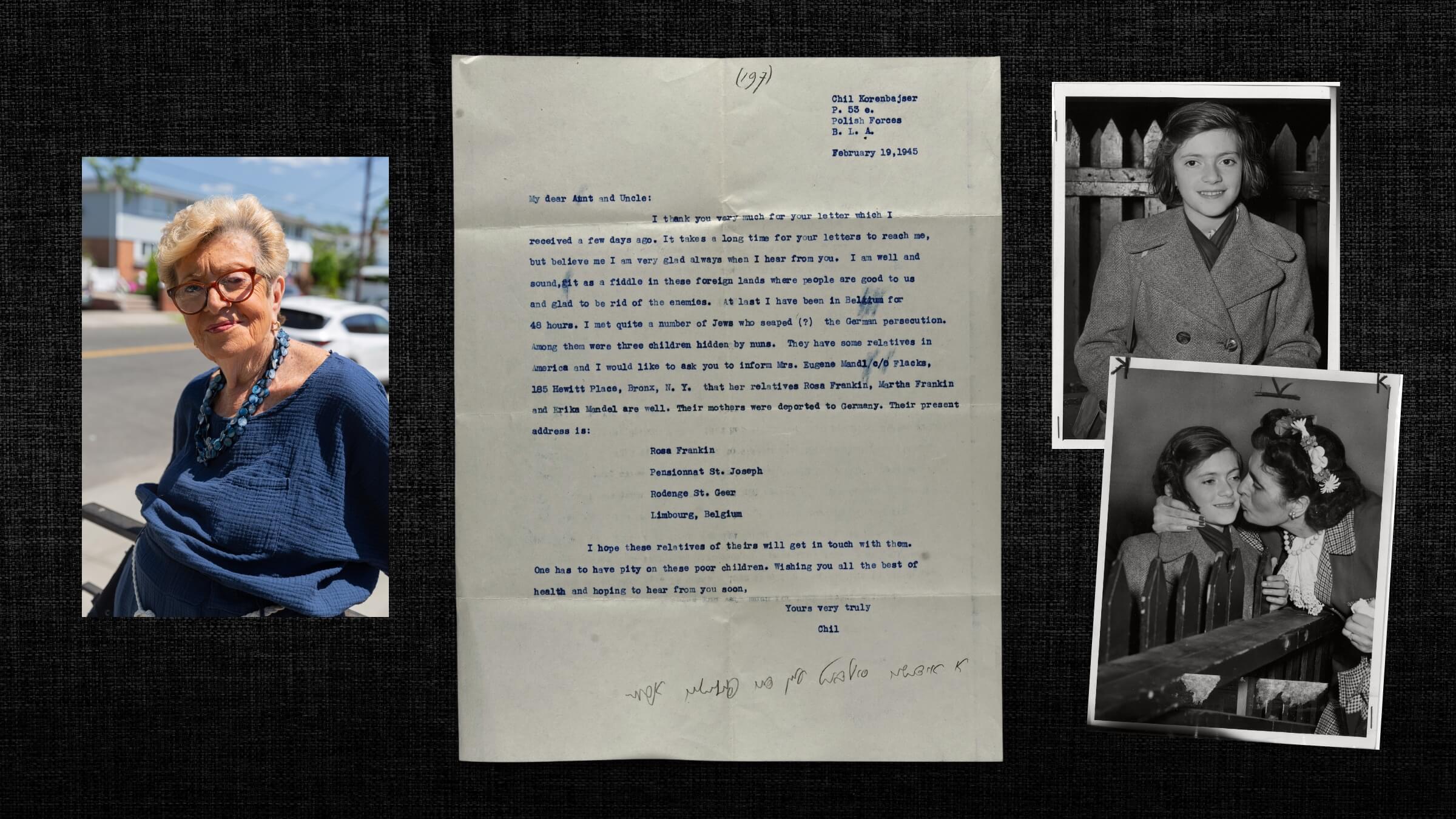

LETTER FROM CHIL KORENBAJSER, FEB. 19, 1945

Hidden by nuns

I have been in Belgium for 48 hours. I met quite a number of Jews who escaped the German persecution. Among them were three children who were hid by nuns … I hope that these relatives of theirs will get in touch with them. One has to have pity on these poor children. (Chil Korenbajser, Belgium, Feb. 19, 1945)

Chil Korenbajser escaped the Warsaw Ghetto and fought with the Polish forces under the British. Two weeks after the liberation of Belgium, he sent a letter about survivors he met there to his own aunt and uncle in Coney Island, who passed it on to the Forward. The paper ran an ad on May 15 and again on June 3.

The letter sought help finding Frieda Mandl. Korenbajser had met Mandl’s 11-year-old daughter, Erika. “They have some relatives in America,” he wrote.

Erika Mandl Fuld, who was hidden by nuns in a convent in the Belgian town Roclenge-sur-Geer, is now 88 and lives in Howard Beach, Queens. She did not know about the letter or remember Korenbajser specifically; she said she’d been told that her mother asked an American soldier heading to Belgium to try to find her.

“This is giving me chills,” she said when I showed it to her.

Fuld, who was born in Vienna in 1935, also has no memory of saying goodbye to her parents when she went to the convent.

Her father, Eugene, was a tailor. He was sent to a concentration camp after Hitler annexed Austria in March 1938. At that time, the Nazis released Jewish prisoners who could emigrate; Eugene Mandl, with the help of relatives in Pennsylvania, made it to the U.S. on Dec. 6, 1939.

Erika and her mother, Frieda, went to live with relatives in Belgium while waiting for their immigration papers. Frieda’s visa came first, and she went to London to wait for her daughter. By the time Erika’s visa came, the Nazis had invaded Belgium.

Erika’s aunt, uncle and grandmother went into hiding in a farm loft but “were sent to a concentration camp right before the end of the war,” Fuld told me. They did not survive.

She and two cousins, Rosa and Martha Frumkin, and three other Jewish girls, hid at the St. Joseph convent, which was run by French-speaking nuns involved in the resistance.

Erika, who was at the convent from age 5 to 11, can still recall the smell of the potatoes and onions in the cellar where the students hid during bombing raids — the only times she remembers being afraid. For six years, she went by the name Marie Lambert and spoke only French.

“They showed me a picture of my mother and father, and asked me, ‘Who is that?’ I said I didn’t know,” Erika told me. “But my older cousin wouldn’t let them baptize me, because she always had hopes that one day we would be reunited with our family.”

Fifty years later, Erika’s cousin Martha was asked during her testimony for the USC Shoah Foundation how the cousins were reunited with Erika’s family. She recalled an American soldier after liberation who promised to look for Erika’s parents. “They found out that the mother and father lived in New York,” she said, “but it took, I think, a whole year before the papers, and until everything was settled for her to go.”

Korenbajser fought with the British, not the Americans, but the timing matches. On June 4, 1946, a year and a day after the second Forward ad, Erika returned to her parents in New York. Her mother spoke to Erika in German, but she responded in French. She also had a new baby brother. “I Americanized real fast,” she told me, in a New Yorker’s accent.

A year later, Erika’s father helped her two cousins come to New York. The three spent summers in the Catskills, where Erika’s mother worked as a baker and later owned a small hotel. In 1959, Erika married Edwin Fuld, the son of a hotel guest.

They raised a son and a daughter in Howard Beach. Edwin, who operated discount shops in New Jersey, died of COVID-19 in 2020; Erika, who worked in sales for a car service until she was 80, now lives with her daughter and enjoys playing mahjong.

Decades later, her cousin Martha exchanged holiday cards with the Belgian nuns. The convent’s Mother Superior was awarded the honor of “Righteous Among the Nations” by Israel. Erika attended a ceremony at the convent, where she was shown the secret tunnel the nuns dug under a tree in case they needed to hide the girls.

“One time, a Nazi came in and he tapped me on the head. In German, he said, ‘Pretty little girl,’” Erika told me. “Can you imagine that poor nun? They would shoot the nuns on the spot right there and then.”

LETTER FROM WILLIAM SHAPIRO

Soldiers’ stories

When William Shapiro, a 26-year-old private in the U.S. Army, went to Bergen-Belsen after it was liberated by the British, the prisoners were shocked and moved that he spoke Yiddish and wore a Star of David around his neck. He recounted the experience in a five-page, handwritten letter home to Jersey City asking his family to place an ad in a newspaper in hopes of locating relatives of three survivors.

“I am the first American Jew that most have seen,” Shapiro wrote, “They started to cry when they saw me and a lot came up and kissed me. They couldn’t get over the fact that I am Jewish and admitted it.”

That letter ended up in Isaac Metzker’s files at Yad Vashem. Notes on it suggest that two of the survivors, Sala Kotovsky and her daughter, were connected to an uncle in Brooklyn.

Civilians were not allowed to send mail out of Allied-occupied Europe until 1946, so the help of soldiers like Shapiro was essential. But the Army’s rules against fraternizing made such interventions risky. When Rudolph Braun, a soldier’s father, wrote to the Forward in July 1945 to help two “Hungarian Jewish (slave)-women” his son had met at a displaced persons camp, he asked that his name not be published “as I understand it is against Army regulation to have anything to do with the encamped people.”

Still, letters from Jewish soldiers poured in. Many of them had roots in Europe, and were confronting what the Holocaust meant for their own families.

Irving Schilit, the soldier who helped reunite Regina Schiff with her family in Brooklyn, had come from Poland when he was 9. After the war, Schilit searched for his own cousins in a DP camp. The cousins later came to New York.

“He helped them get acclimated to the states,” said Schilit’s daughter Audrey Berman Schilit, a retired New York City schoolteacher. “He gave them money to start businesses. They opened stores on Orchard Street.”

Another soldier, Jack Fliegelman, who had come to the U.S. from Poland at age 6, wrote home in July 1945 that he had asked a group of survivors at Dachau about his uncle’s shtetl.

“I asked them about mom’s brother in the town of (Selanoff) in Galitzy,” Fliegelman wrote. “They told me that they don’t think that any Jews are alive in that town.”

This letter also ended up in Metzker’s files because Fliegelman was asking his family to help a survivor — Yankel Weissbaum, a shoemaker seeking relatives in Roxbury, Massachusetts. Weissbaum came to the U.S. in 1950, and married another Polish Jew two years later, in Nebraska.

Sometimes the Forward turned letters from soldiers into articles. One featured Cpl. Irving Chattman, who wrote to Seeking Relatives from Linz, Austria. There are more than two dozen pages from him in the archives.

“My father was an interpreter for the Army, and he was one of the first ones into Mauthausen,” Chattman’s son, Gary, told me. “He never talked about it. It was too painful.”

But after Irving’s death in 1979, Gary, a retired New York City schoolteacher, found a 1946 Forward clipping with his father’s photo. The article, written by Metzker, begins: “Mr. Irving Chattman, from New York, a former corporal in the American Army, who has just returned from overseas, has brought us in-depth greetings from thousands of Jews still alive in Austria.”

Irving Chattman was born in Lyubar, Ukraine, around 1907. His family came to New York in 1921, following a pogrom in their town that killed 50 Jews and injured 180.

In his letters to the Forward, Chattman was critical of the military’s treatment of the refugees. “The people at this camp need clothing, soap and some more food,” he wrote on July 10, 1945. “Many of the kids are dressed up in S.S. Officers’ uniforms, but most walk around half naked, worried looking, their faces shrunken.”

Though some of the children were “so weak they can hardly walk,” he added, U.S. soldiers punished them for stealing vegetables from nearby gardens by locking them in rooms without food for 24 hours.

The article, published after Chattman had been discharged from the Army and had returned to work in his family’s furniture shop, credited him with successfully petitioning the commander of U.S. forces in Austria to improve the conditions.

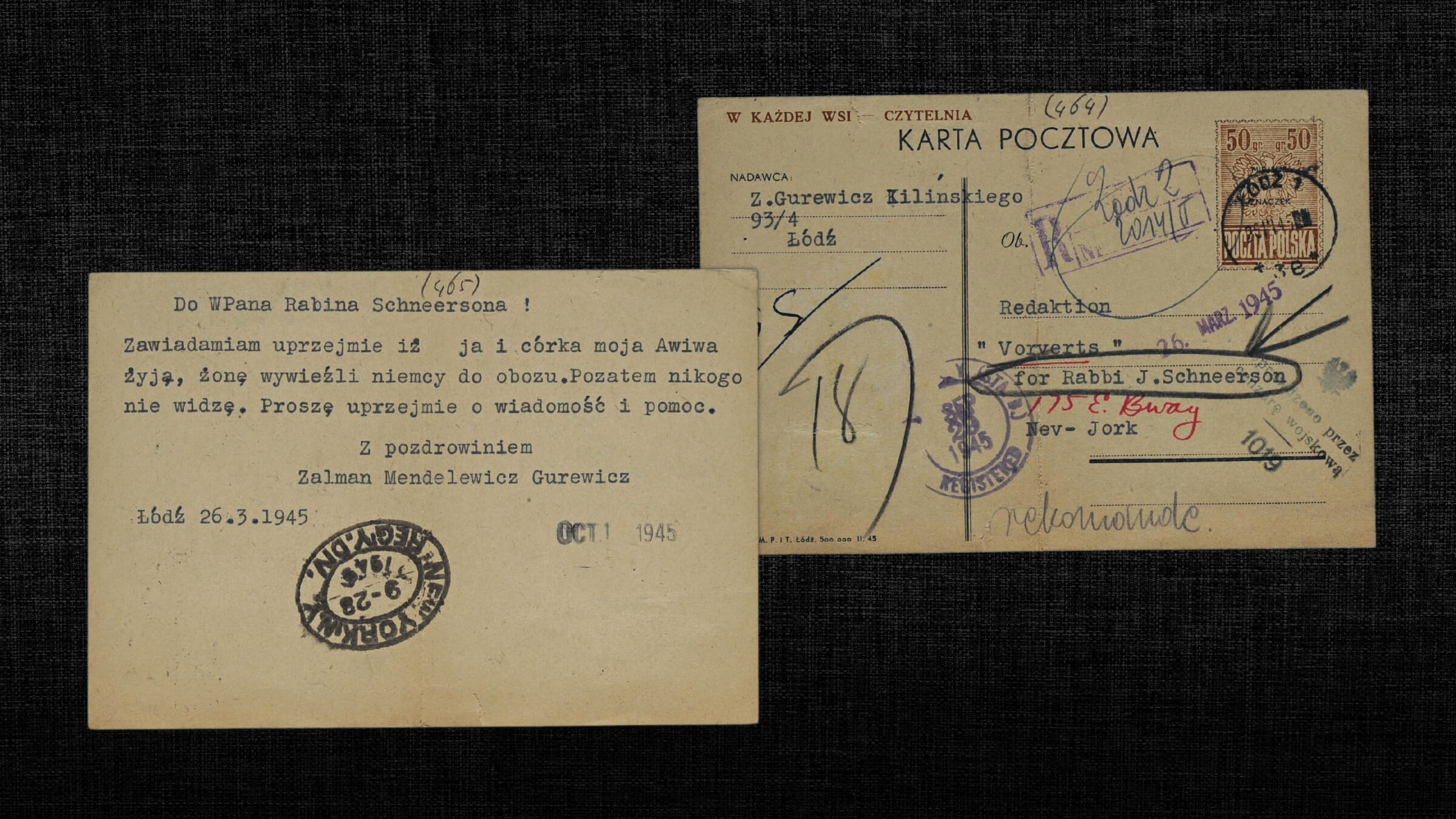

LETTER FROM ZALMAN MENDELWICZ GUREWICZ, MARCH 26, 1945

Letter to the rebbe

I kindly inform you that my daughter Aviva and I are alive, my wife was taken to the camp by the Germans, but besides us I don’t see anyone. I ask you kindly to write back and send help. (Zalman Mendelwicz Gurewicz, Lodz, Poland, March 26, 1945)

This three-line, typed postcard was sent to the Forward weeks after Lodz, Poland, was liberated by the Red Army. It took six months to arrive in New York. Seventy-eight years later, I showed it over Zoom to Aviva Greenberg, now 88, at her home in Montreal. Her daughter and son-in-law listened closely along with me as she slowly translated the message sent by her father, Zalman.

Aviva was hidden in a Christian orphanage during the war. “My father found out where I was, and he came to get me and we walked for a couple of days,” she remembered. They dug potatoes from the ground and ate them raw.

Gurewicz, then 42, had escaped the Warsaw Ghetto through the sewers. He gave his business, which produced paper bags, to his employees. One hid him for two years in a secret room in the factory. “She saved him,” Aviva told me.

Aviva’s mother, Cilia, survived by passing as a gentile and working in the kitchen of a labor camp. “My mother spoke German. They didn’t know she was Jewish,” Aviva explained. “She was blond.”

Not mentioned in the postcard was Aviva’s older sister Chana, who had been sent to live with her maternal grandparents in Riga, Latvia. “She looked like my grandmother,” said Aviva’s daughter, Marlene Arbess. “My family used to say she had long eyelashes and she was beautiful.” On a visit to Yad Vashem, Arbess learned that Chana was killed in Riga at age 9.

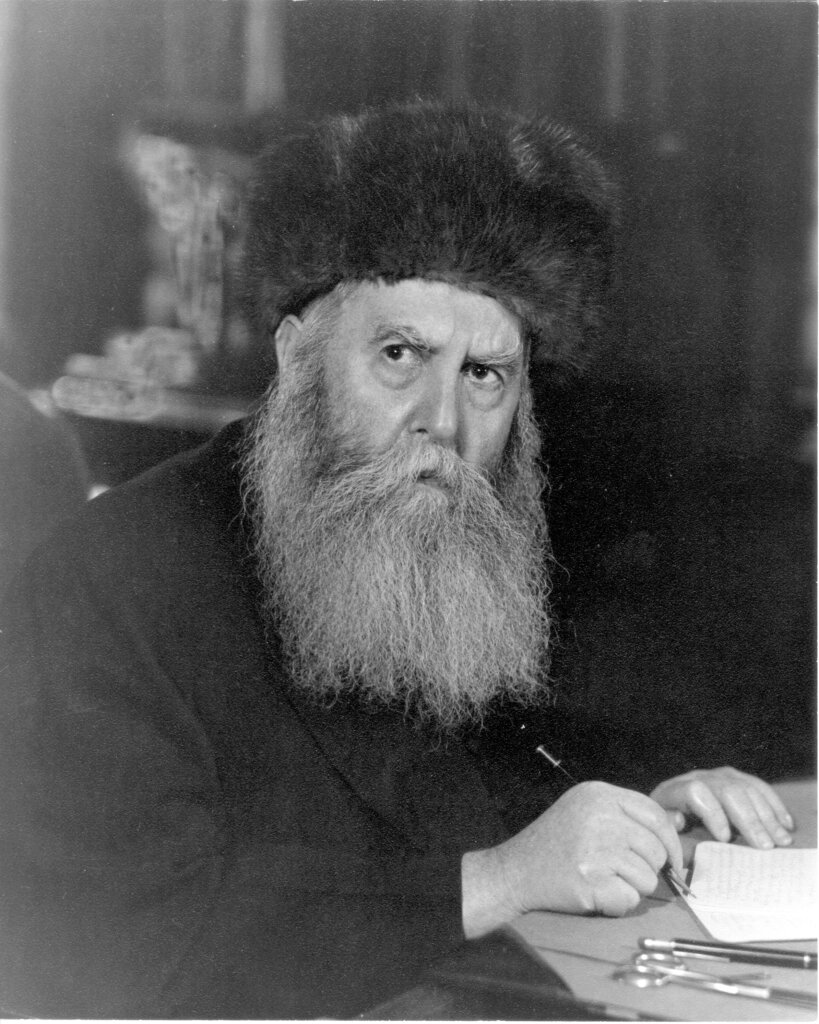

While Aviva’s father’s postcard was addressed to the Forward Building, its message was intended for the sixth Lubavitcher Rebbe, Josef Schneersohn, who had fled Warsaw after the Nazi invasion and arrived in New York in March 1940.

And he was not alone in reaching out through the Forward to Schneersohn, who headed the Lubavitcher-Chabad movement in Crown Heights, Brooklyn. The Aug. 26, 1945, Seeking Relatives column includes a notice of a letter for the rebbe from Berel Zisman, 16, who had survived Dachau and was in a displaced persons camp in Germany.

Zisman, who died in May 2021, came from a prominent Lubavitch family in Kovno, Lithuania. In his 1998 testimony to the USC Shoah Foundation, he recalled how a Jewish American soldier named Haskell sent a letter for him to the secretary of the Lubavitcher Rebbe. The secretary, a family friend, helped Zisman and his brother Leib connect with two uncles in Philadelphia.

“I did not know the rebbe’s address,” Zisman recounted. “Sure enough, a few weeks later, Haskell comes and says I have a letter for you.” The following year, Berel and Leib Zisman spent Hanukkah at the rebbe’s home in Crown Heights.

The Gurewicz family never made it to New York.

“They went to Poland, but there was antisemitism,” Zalman’s granddaughter told me. “They went to Germany, there was antisemitism. Then they went to Paris, where they stayed for two years.” In the early 1950s, they settled in Montreal, where Zalman built a successful paper-bag business and later built a Chabad school for girls in memory of his daughter Chana.

His other daughter, Aviva, has three children and nine grandchildren. She and her husband, the real estate developer Sam Greenberg, helped open Chabad’s The Shul of Bal Harbour in Florida in 1994. Their daughter Marlene and her husband, an investor, founded the Chabad center in Prague in 1996 in Zalman’s memory.

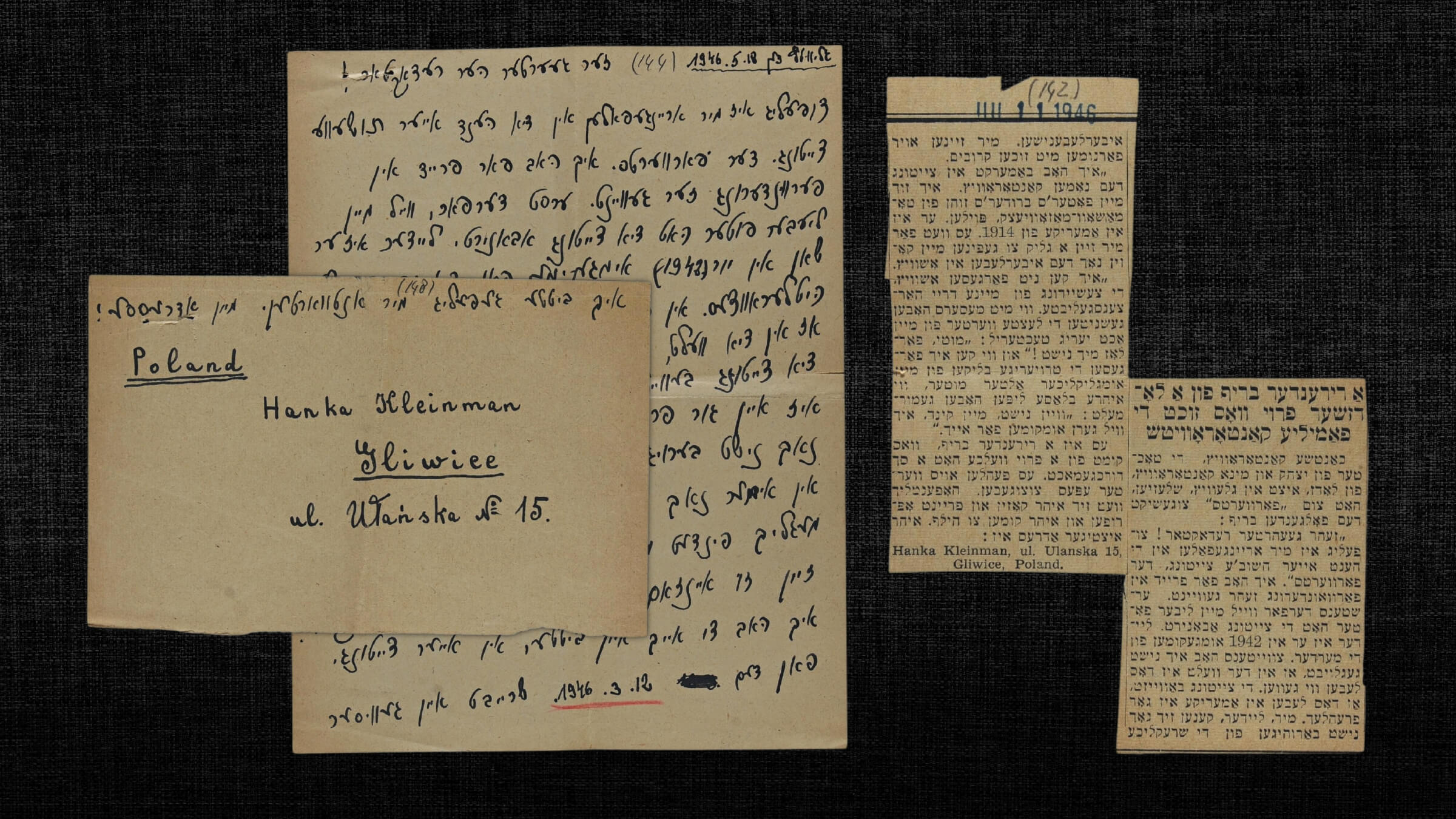

LETTER FROM HANKA KLEINMAN, MAY 18, 1946

A forgotten family

I happened to find a copy of your important newspaper, the ‘Forverts.’ I wept extensively from joy and surprise. Firstly, because my beloved father was a subscriber. Secondly, I didn’t believe the world was still continuing to live as seen there … life in America is a happy one. (Hanka Kleinman, Gliwice, Poland, May 18, 1946)

I happened to find a copy of your important newspaper, the ‘Forverts.’ I wept extensively from joy and surprise. Firstly, because my beloved father was a subscriber. Secondly, I didn’t believe the world was still continuing to live as seen there … life in America is a happy one. (Hanka Kleinman, Gliwice, Poland, May 18, 1946)

Hanka Kleinman wrote after spotting the name of a cousin who had emigrated to the U.S. four decades earlier. Her letter to the Forward was not published in Seeking Relatives, but in a section titled “Letters from Destroyed Jewish Cities and Towns.” In poetic prose, she described a loss so horrific that she would carry it as a secret for the rest of her life.

Kleinman’s daughter, Frances Kleinman, is a semi-retired literature professor who lives in the Bayside, Queens, home that her parents bought in 1957. She told me that her father, Sam, freely spoke about fleeing Lodz for the Soviet Union and, after a stint in Siberia, fighting with the Red Army. But her mother, who died in 1999, had hardly discussed the past.

Frances was of course curious to learn more about her mother’s life during the war, so I read her a translation of the letter:

I will not forget the separation in Auschwitz, the tragic cries of anguish … from my heartfelt beloved three … As if slashed with knives are the last words of my 8-year-old beloved little daughter, Muti! Don’t leave me, I’ll kill myself … and how can I forget, the sad glances of my unfortunate elderly mother, how her pale lips murmured … don’t cry my child, I will surely die before you do …

Frances listened closely. She had been piecing together her mother’s story since she was a child of perhaps 13. That’s when she opened a letter that arrived at their home from Australia. It was from the third of the “beloved three”: a son, Arthur Shynton. When Hitler invaded Poland, Frances said, Arthur was preparing for his bar mitzvah; his sister was a toddler. Hanka had split from their father after an arranged marriage when she was about 17.

Arthur survived Buchenwald and Auschwitz, and in 1949 located his mother in Germany. By then, Hanka was with her new husband, Sam, and their new baby, Frances.

“Dad asked him if he wanted to come with us to America, but he already was issued a Swiss passport through the Red Cross, and his plan was to go to Australia,” Frances told me. He joined the Australian army and married in Brisbane, “and no one in Australia knew he was Jewish.”

Hanka, an Orthodox Jew in Poland, became Ann, a secular Jew in Queens. For the next 50 years, she never spoke about her previous family. Though she was born in 1909, she listed her year of birth on her U.S. documents as 1917, two years after Sam, to help fit her story.

Frances met Arthur, who was 21 years older, several times. She described him as tall and handsome, and with no trace of a European accent — or knowledge of the family’s history. “He didn’t remember anybody,” Frances told me. “No one at all. He had blocked all of that out.”

Her father eventually told Frances that there had also been a little girl. But all she knew was that the girl’s name started with an “M.” She tried for years to find more information on genealogy websites, with no success.

“I didn’t know how the daughter died or when the daughter died,” Frances said. Until I read her the letter.

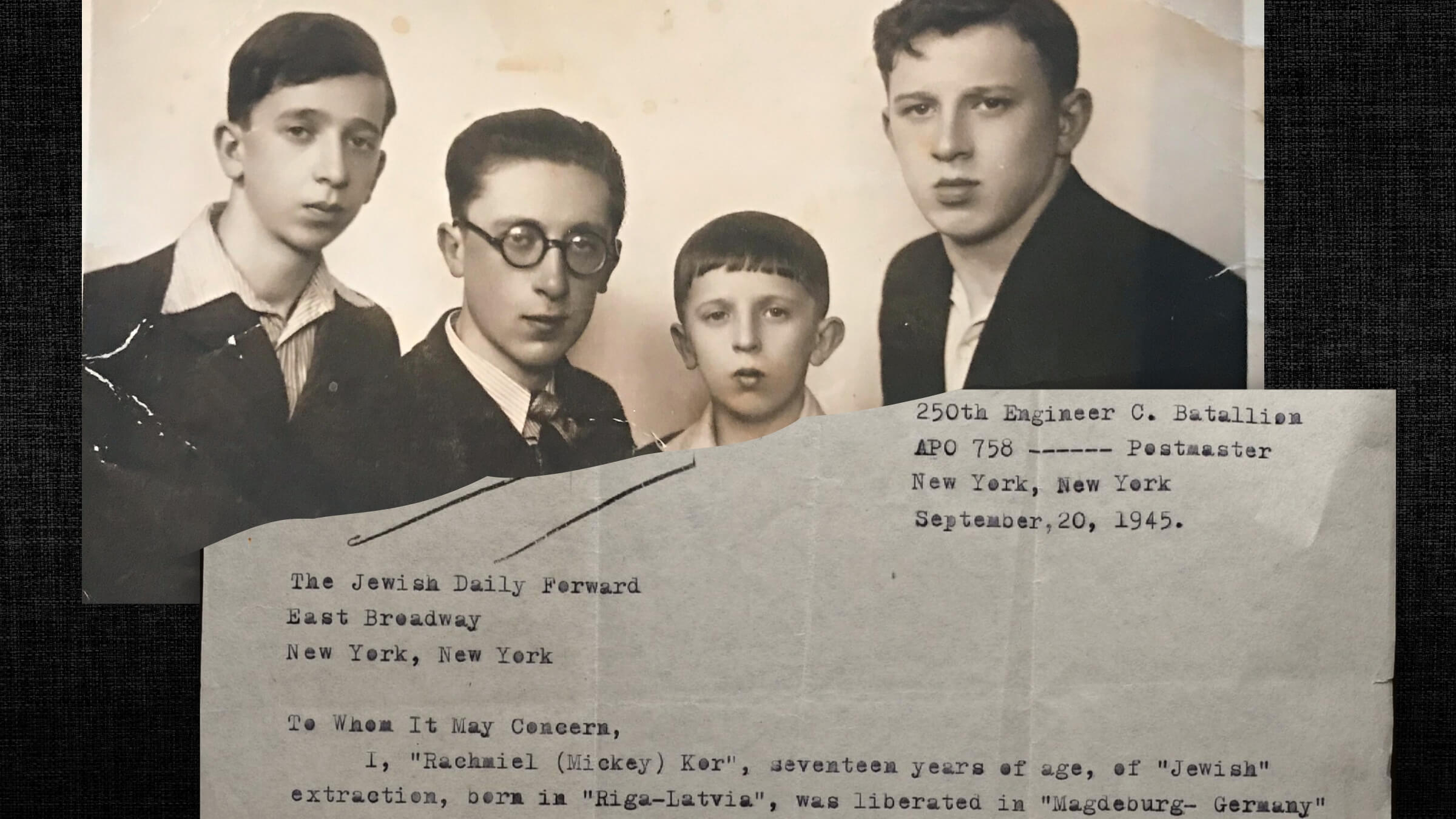

LETTER FROM MICKEY KOR, SEPT. 20, 1945

Aspiring American

At the age of 12 1/2 years, the ‘Nazis’ murdered my family in a cold-blooded manner before my very eyes, including my mother, my father, and my three brothers. I am now alone in the world, and not knowing where to turn. (Mickey Kor, Magdeburg, Germany, Sept. 20, 1945)

The letter was typed, in English. The writer, now 17, was not seeking help finding his relatives in the United States. He didn’t have any.

Mickey Kor was born in Riga, Latvia, and had survived four years in labor and concentration camps. Since the soldiers gave him his first bottle of Coca-Cola when they liberated him in April 1945, he had wanted to come to the U.S.

I’ve been issued the regular Army uniform, ate and slept with the boys, and became one of their buddies. As time went on, I acquired knowledge of the ‘English’ language; and today I am proud to say that I am truly “American” in every [aspect], except fact.

A photo from that time period shows Kor in an American Army uniform a couple sizes too large, eating an ice-cream sundae out of a glass with a Coca-Cola insignia on it.

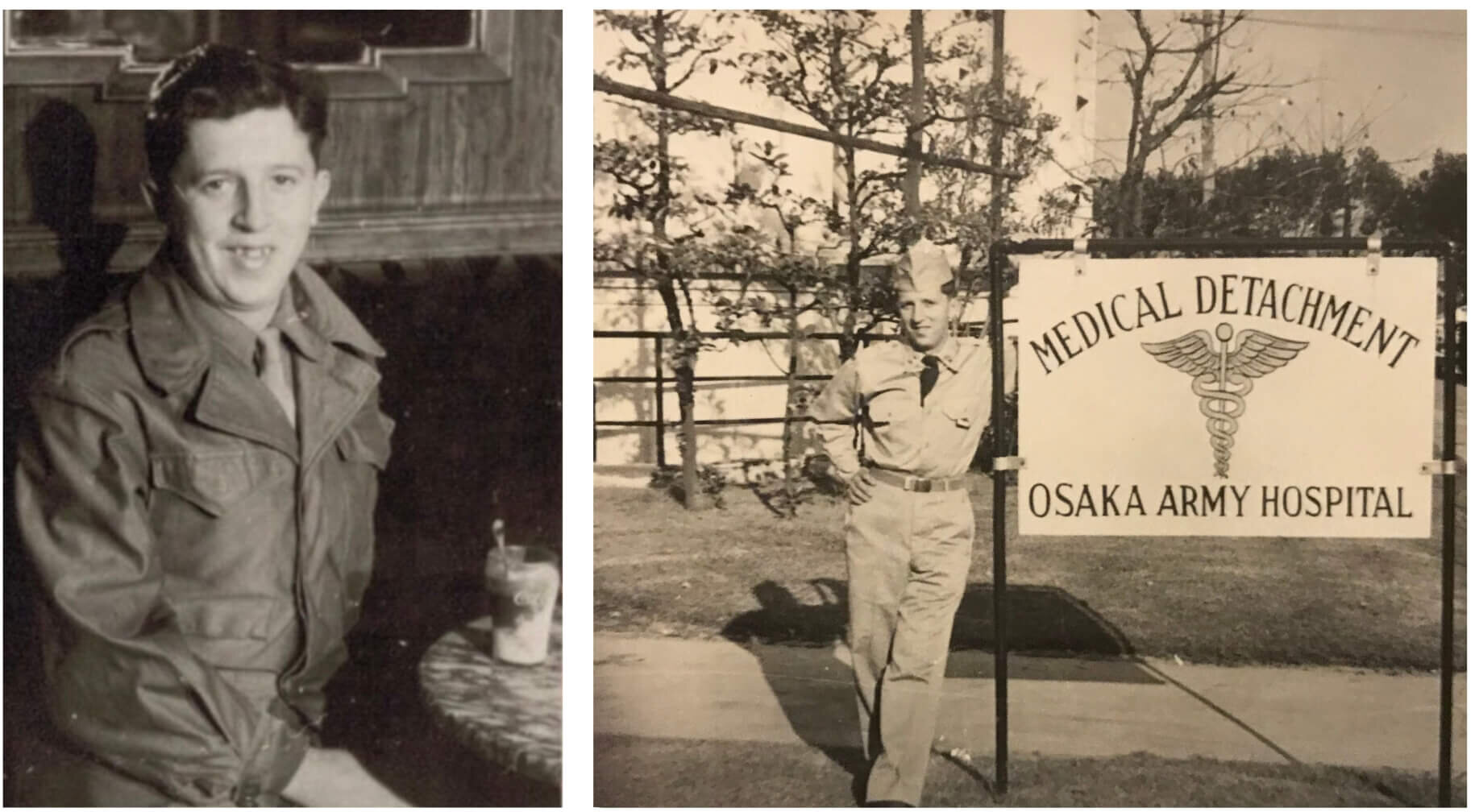

He ended up on the first ship of survivors granted refuge by President Harry S. Truman, in May 1946. One of the soldiers who liberated Kor, Lt. Col. Andrew Nehf, had found him a Jewish foster family in Terre Haute, Indiana, just a few houses down from where Nehf himself lived. Kor entered the local high school, his first time in a classroom since the Nazis invaded Latvia five years before.

He graduated from Purdue University in 1952, and once again wore the U.S. Army uniform — now as a military pharmacist in Osaka, Japan, during the Korean War. This time, they got the size right.

In 1960, while visiting Israel, Kor met Eva Mozes, a survivor from Romania who was an identical twin experimented on by the notoriously cruel Nazi doctor Josef Mengele. They married and raised two children in Terre Haute, remaining close to the Nehf family.

Eva, who died in 2019, founded the Terre Haute museum and organization “CANDLES” (Children of Auschwitz Nazi Deadly Lab Experiments Survivors). Mickey, a pianist and a fan of Dean Martin and the Purdue football team, died in 2021.

Their son Alex, a podiatrist who lives near Indianapolis, has amassed a cache of family historical documents. But he had never seen his father’s 1945 letter or the Forward article that followed it. He was shocked when I showed him what 17-year-old Mickey had written.

I want to forget the terrible past. I look forward to the future and the hope that somehow, I will be given the opportunity of entering the country of the ‘United States of America’ and be a useful citizen.

His wish came true.

The end of Seeking Relatives

Seeking Relatives continued to run long after the war. But by the 1970s, it was a shadow of its former self. The Forward charged $5 for each listing.

In 1977, Yitshok Shmulevitsh, a Forward writer who had survived the Holocaust in a Soviet gulag, recalled hearing people talk about the column during a postwar visit to his native Poland.

“Jewish survivors felt they had a particularly good friend in the Forward,” he wrote. “Thanks to this feature Seeking Relatives, our paper was able to reunite those an ocean apart.”

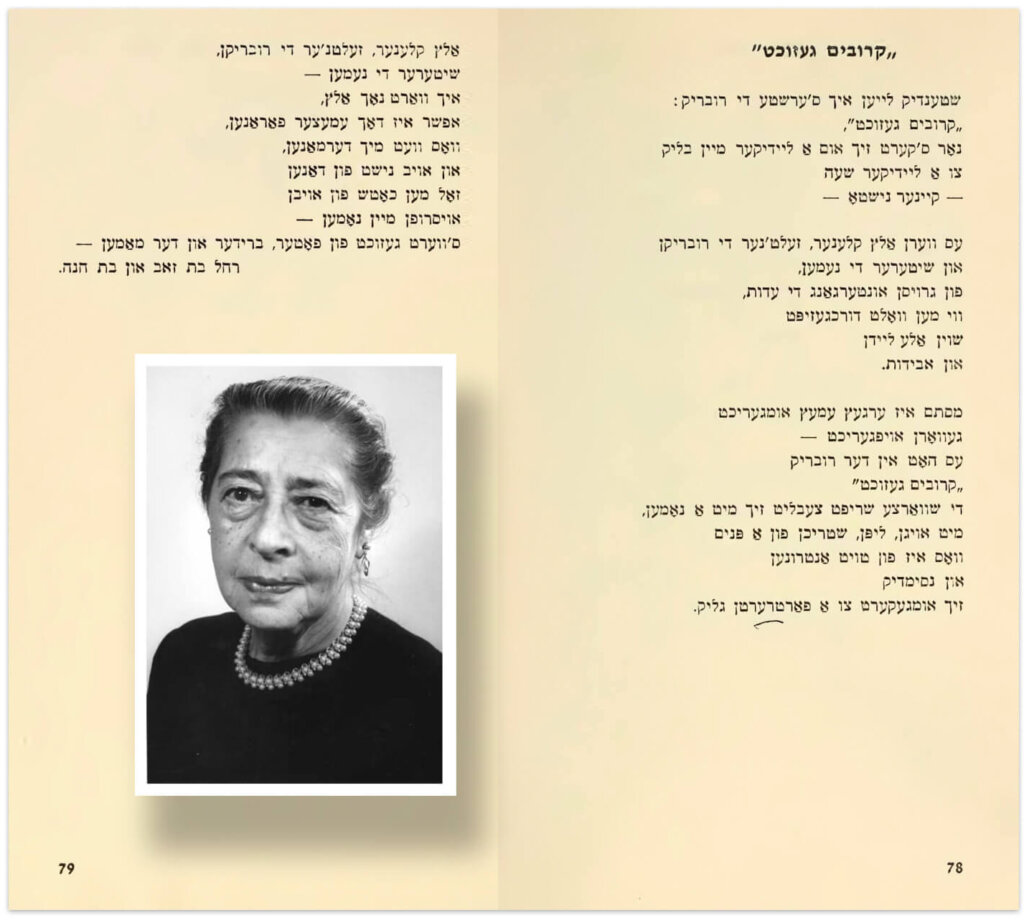

Five years earlier, the poet Rokhl Korn published a verse, translated here by Miro Miniewski, lamenting that the listings had grown sparse. She and her daughter were the only ones in their family to survive the war.

The column I always turn to first

leaves my gaze deserted

empty with

— no one there

That feature

published less and less

gets smaller as witnesses

of the great destruction

fall into decline.

By the 1980s, the column had disappeared.

The Story Behind This Story

Meet the editor who ran the column: Isaac Metzker, the Forward editor who oversaw Seeking Relatives for years and whose archives contained thousands of original letters from survivors and refugees, didn’t like to talk or write about the Holocaust.

How we did this project: More than a year ago, Andrew Silverstein stumbled upon a pair of handwritten letters from 1939 written by cousins named Joseph and Avrom Gross. That led him and archivist Chana Pollack on a fascinating, painstaking journey.