In remote North Dakota, endless sky, a few gravestones, and the remnants of a little-known Jewish history

While most Jewish immigrants flocked to urban centers, a few — like the Greenbergs — tried their luck as homesteaders

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

In the northeastern corner of North Dakota, roughly three miles east of the well-named village of Starkweather, on a small patch of unfenced land under a boundless sky, huddles a handful of tombstones. Some are hewn from granite and others are hammered from rusting tin, yet nearly all are more than a century old. While this burial ground place is striking, it is hardly strange. Where else but on this sea of windswept wheat would one find the graves of homesteaders who, in the tens of thousands, flocked to the Dakotas in the late 19th and early 20th centuries?

In his book Bad Land, the travel writer Jonathan Raban, gazing at a North Dakota graveyard, wonders about the impact these vast and often violent plains had on European settlers who believed that America promised them a kind of redemption. “Looking at the fleet of lonely derelicts on the prairie, awash in grass and sinking fast, I could guess at how that faith had been shaken.” Raban’s wonder might have deepened had he visited this graveyard, though. The names on the grave markers are not Norwegian — the original home of many settlers — but instead Jewish. Some of the inscriptions, on wood or tin, are too faded to read, but others are carved in granite not just in English, but also Hebrew: Joseph Canter (1905-1918); Anna Canter (1902-1914); Mandel Hill (1860-1935); Joseph Adelman (died in 1907); Israel Greenberg (1892-1903) and Charlotte Greenberg (1902-1906).

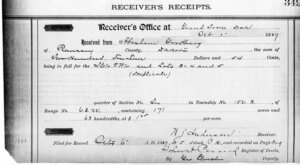

Last year, I learned about this graveyard from Joyce Greenberg, a formidable student of American-Jewish history, who is also the widow of Jacob Greenberg, the brother to Israel and Charlotte Greenberg, and the youngest child of Philip and Mollie Greenberg, who had emigrated from eastern Europe a few decades earlier. The youngest of the nine surviving siblings — he never knew Israel and scarcely knew Charlotte — Jacob was born in 1904 on a homestead in the northernmost reaches of North Dakota. The homestead was so far from the nearest town that when Jacob applied for a passport, “North Dakota” had to suffice as his place of birth.

Joyce might as well have announced that her late husband had been beamed down from a UFO over Roswell, New Mexico. Yet, once I began to research the history of the Greenberg family, my astonishment only deepened. The Greenbergs happen to represent one of the most fascinating currents of the great river of East European Jewish immigrants — more than 2 million — that flowed in America between the early 1880s and mid-1920s. Though the great majority settled in New York, where more than 1.5 million remained, several thousand found their way to the Great Plains, staking claim to 160 acres with the promise that, after five years of back-breaking labor, the land would become theirs.

That relatively few Jewish immigrants set out on this adventure — an adventure, moreover, that many of them did not see through for five years — does not take away from its importance and interest. To the contrary. On the eve of the centenary marking the passage of the 1924 Immigration Act — the racist law that slammed shut the door on “undesirable” foreigners seeking to immigrate to America — the history of these shtetl-born Jews who sought to redeem the land not of Eretz Israel, but instead North Dakota, bears telling.

‘In an alien, heathen land, harsh and bare and hostile’

Little in the lives of these thousands of Eastern European Jews suggested that, once processed at Ellis Island, they would proceed to find their way to North Dakota as homesteaders. Prevented by laws from owning land in Czarist Russia, few Jews had known the life and learned the skills of farming. Most were traders or peddlers, wholly dependent on the commerce provided by close-knit communities nestled in urban ghettos or rural villages. In fact, not only did they lack the practical means to work the rocky soil of the high plains, they lacked the conceptual means to even form an idea of such a life. In her austere memoir Dakota Diaspora: Memoir of a Jewish Homesteader, Sophie Trupin describes this sense of imaginative disconnect. Soon after landing in the U.S. with her family, Sophie began to hear a mysterious word. They were bound for “Nordokata.” It was there that “our traveling would come to an end. We had no idea what it would be like. But whatever it was, we would finally rest.”

What they found, however, gave them little time to rest. These settlers had escaped the densely populated world of the ghetto, marked by shared religious and cultural traditions and wracked by spasms of antisemitic violence, for a world free not just of antisemitism, but free of most everything else they had associated with normal life. For the Greenbergs and their fellow Jewish homesteaders, this brave new world resembled the one that greeted Sophie Trupin: “An alien, heathen land, harsh and bare and hostile.”

Oddly, the material conditions of these immigrants in the northern fringes of North Dakota often resembled the material conditions of immigrants in the Lower East Side. Privacy was as rare a commodity as indoor plumbing. The Trupins trekked to the well dug “at the foot of the hill upon which our house stood,” while others had to move their shanties to accompany the wells they had to dig. Heating during the winter was also a dicey affair in both the urban and rural settings; in both places, families often depended on the heat generated by bodies snuggling close together to survive cold nights. Even the intensity of labor was similar in both worlds. Many immigrants trapped in the infamous sweatshops of New York’s Lower East Side were also forced to work 15-hour days (and nights), not unlike the unrelenting labor of the men who tilled the Dakotan soil. “It seems to me as I look back,” Sophie Trupin writes, “all the rows and heaps of rocks that lay along each cleared field were stained with the sweat of these zealots.”

There were other similarities — threats of asphyxiation from smoking stoves; of fires sweeping through a sweatshop or a wheat field — but there were even more important differences. On Manhattan’s Lower East Side and Chicago’s Maxwell Street, one could not help but breathe Yiddishkeit. The language and culture, institutions and practices of European Judaism were omnipresent. On the plains of North Dakota, however, remaining Jewish proved as arduous as becoming prosperous. Time and again, another Jewish pioneer, Rachel Calof, recalls the challenges that Jewish law imposed on her family’s struggle for survival. During their second and especially harsh winter on the homestead, the family, which had little else than wheat seed for nourishment, never butchered their cow or one of their oxen. The reason was simple: “I don’t believe it ever occurred to anyone to kill or eat an animal that had not been ritually slaughtered according to the precepts of our religion.”

Forsaking the old world for the new

Nor does it appear to have occurred to the American Jewish immigration agencies that it was madness to send unskilled and unprepared immigrants to work the Dakotan soil. If there were doubts, they were suppressed because the situation was deemed to be desperate. Staffed by a de facto aristocracy of German-Jewish Americans, these agencies — the Jewish Agriculturalists’ Aid Society, Hebrew Emigrant Aid Society, and Jewish Agricultural and Industrial Aid Society — feared the impact this massive influx of their Eastern European brethren, so very different in aspect and language from they themselves, would have on the public. “We cannot be blind,” warned one New York charity, “to the fact that the good name of New York Judaism is endangered unless remedial measures are promptly devised to correct the evil … of this unlawful and far-spreading feature of our tenement system.”

These agencies thus wagered they could turn the newly arrived Jewish immigrants into American citizens by rooting them in the soil of the nation. In a word, to become American, these one-time town and urban dwellers were literally farmed out to rural America to cultivate not just the land, but their characters — to take root and grow into Americans. As the German-Jewish paper The American Israelite trumpeted, the resettling of “persecuted, down-trodden and degenerated Hebrews” would soon “restore the race to its pristine character.”

A driving force behind this movement was Maurice de Hirsch, the Belgian billionaire and philanthropist. In 1891 — when colonization was still portrayed, if only by the colonizer, as a noble pursuit — Hirsch founded the Jewish Colonization Association. Based in London, the JCA’s mission was, in Hirsch’s words, “to give a portion of my companions in faith the possibility of finding a new existence, primarily as farmers … in those lands where the laws and religious tolerance permit them to carry on the struggle for existence.” Hirsch plowed part of his fortune into furnishing plows to Jews. While his contemporary Theodor Herzl argued that European Jewry could be free only by embracing their Jewish identity in a Jewish state, Hirsch insisted they could be fully free only by shedding their Jewish faith and settling in a secular state. “The Jewish question,” he asserted, “can only be solved by the disappearance of the Jewish race.”

Where better to disappear than the southern pampas of Argentina, a sparsely populated nation eager to grow, or the northern prairies of the fledging states of the Dakotas, equally keen to populate the land? By forsaking their homes in the Old World and founding settlements in the wild places of the New World, these Jewish pioneers in turn would be reborn.

In 1882, a first wave of Jewish immigrants settled on a partly forested tract of land several miles north of Bismarck. Called Painted Woods, after the name of the closest village, the colony quadrupled in size from 1882 to 1885, from an initial dozen families to more than fifty Russian and Romanian families in 1885. By then, the colony boasted large herds of cows and oxen and tilled more than 1,400 acres of land. But the experiment was short-lived when a series of unusually harsh winters, dry summers and a prairie fire overwhelmed the fledgling farmers. By 1886, the settlers quit Painted Woods for nearby cities in neighboring states, leaving behind a school district called Montefiore, named after the Jewish philanthropist Sir Moses Montefiore, as the only sign of their passing.

Nevertheless, new waves of immigrants continued to spill into North Dakota. As early as 1882, roughly two dozen Russian Jews, with the help of the HEAS, purchased homesteads near the village of Garske in Ramsey County. After two years of punishing weather and failed crops, the settlers — described in one report as “inexperienced, thoughtless and very poor” — left their homesteads for other settlements or towns. As for their houses, built with sod because of the lack of nearby lumber, they slowly subsided into the same soil from which they had been scraped.

Other settlements, however, proved slightly more resilient. Near the town of Devils Lake, the number of Jewish homesteads grew from 10 to more than 40 by 1889. The community had, in fact, grown large enough to merit its own post office that the settlers named Benzion. This name was proposed by its first (and last) postmaster, Philip’s brother Benjamin Greenberg, who believed the settlement was a new Zion. At first, his hopes did not seem utterly utopian. By the end of the decade, the settlers were cultivating about 3,500 acres of wheat and flax fields. Yet the crop yield was not enough to cover the bills, much less pay back earlier loans, often tied to high interest rates from Jewish organizations based in the Twin Cities. Like its sister communities, the Devils Lake settlement also faded and disappeared. The trace they left is ghostly: A 1965 census revealed that only three of nearly 50,000 households in rural North Dakota had even a smidgen of Jewish ancestry.

‘We tamed the land’

According to J. Sanford Rikoon, the pioneering historian of these Jewish pioneers, the average lifespan of a Jewish homestead was seven years. (The Greenbergs were outliers: They remained on their homestead for nearly 20.) But seven years seems right. We are told Yahweh needed seven days to finish and rest from his cosmic experiment. Perhaps seven years was all the time needed for these few thousand Jewish pioneers to finish their earthly experiment, one that did not last long enough to give us a rural equivalent of, say, I.B. Singer. But it did give us Sophie Trupin and Rachel Calof.

At the end of her memoir, Calof wrote, “We could look back with pride on our accomplishments. We had come as raw immigrants without resources or training to a stark wilderness in a strange country, and we tamed the land and made it fit for humans.” By the same token, this achievement, as marvelous as it was slightly mad, is fit to be remembered.