She was an outsider, a Jew and an iconoclastic artist — kind of like Picasso

A new exhibit in Paris explores the friendship between Gertrude Stein and Pablo Picasso

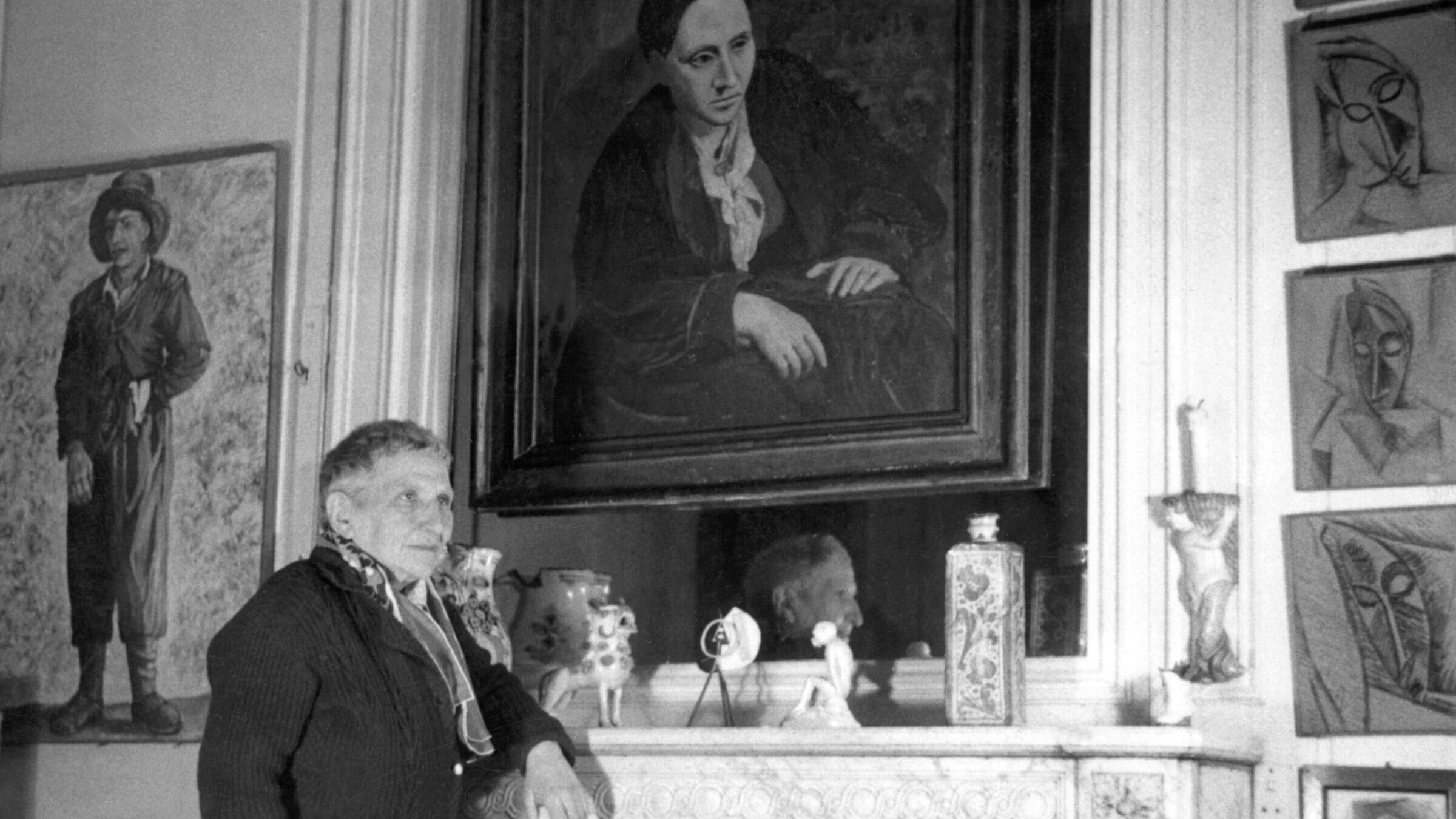

Gertrude Stein poses in front of the portrait of her that Picasso painted in 1906. Photo by Getty Images

“I am a Jew,” the 20th-century poet, novelist, art collector and connoisseur Gertrude Stein once said — “Orthodox background, and I never make any bones about it.”

Stein was in no way observant, but her Jewish background and the Jewish sense of always being an outsider, may have contributed to the openness that allowed her to create new artistic ideas, forms and techniques. Those ideas, forms and techniques strongly influenced her literary output and in turn the modernist avant-garde arts that defined the 20th century, especially in America — as well as the work of a young man, a fellow outsider, who became a close friend, Pablo Picasso.

That friendship and what it led to that is the subject and theme of Gertrude Stein and Pablo Picasso — The Invention of Language, a new exhibition at the Luxembourg Museum in Paris. It is part of what has turned out coincidentally to be a very Jewish-themed autumn at top Paris museums, which are currently showcasing the works of Amedeo Modigliani, Marc Chagall and Mark Rothko.

Stein was born in Pennsylvania in 1874 to an upper-middle-class Jewish family, and grew up mostly in Oakland, California. She moved to Paris in 1903, not long after Picasso arrived from Spain.

“Picasso was a stranger” — also an outsider — “who arrived in Paris at the beginning of the 20th century, and he was pretty poor,” Cécile Debray, co-curator of the Stein-Picasso exhibition and president of Paris’s Musée National Picasso, told me on the phone from Paris. “Neither Stein nor Picasso spoke French.”

“That she was Jewish and a lesbian put her in marginality,” Debray said. For those reasons, and because she was a woman, “she was also a little bit apart in American society,” she continued. “When she came to Paris she wanted to escape from America — from surely its Puritanism but we can imagine also the part of antisemitism.” That she stayed in Paris as a stranger and that Picasso was a stranger was part of their affinity, said said.

“She was also a poet, and Picasso was fascinated by the figure of the poet,” Debray added. “All these things would have counted in their friendship.”

Debray curated the 2011 exhibition Matisse, Cézanne, Picasso … the Stein Family at Paris’ Grand Palais, about the Stein family as art patrons and collectors, “and for a long time I wanted to do more on her poetry and its relationship with Picasso and the relationship with painting,” Debray said.

“I feel that she is under-considered in regard to Picasso. I was fascinated by the link between his painting and her poetry at the beginning of the century.”

In planning the exhibit, Debray explored the way Stein “played with language, and the question of representation and interpretation,” and how Stein’s experiments with text can be connected to Picasso’s visual experimentation. Stein’s avant-garde 1914 book of poetry, Tender Buttons, has often been cited for its link to Cubism.

But, Debray said, Stein’s influence went well beyond Picasso.

“When I began to think of this project, I realized that the impact, the influence of Stein’s poetry was very important and very deep in the American arts scene,” Debray said, paying particular attention to the 1930s, when Stein’s Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas — actually her own autobiography but as if written by her longtime companion — was published to great success in America.

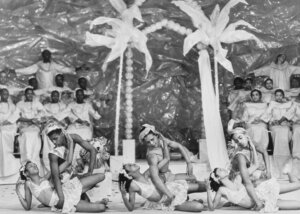

1934 marked the Broadway opening of Virgil Thomson’s deeply unconventional opera Four Saints in Three Acts, with an all-Black cast and a libretto by Stein focusing on the sounds of words.

In addition to Picasso, the exhibition includes works by many prominent American artists, including Jasper Johns, Andy Warhol, John Cage, Steve Reich, Robert Rauschenberg, Robert Indiana, Merce Cunningham, Ed Ruscha and Philip Glass. The French are also well-represented by Henri Matisse, Paul Cézanne, Juan Gris, Marcel Duchamp and Georges Braque.

Stein was also known for her Paris salon, in her home at 27 rue de Fleurus, where she — and for the first decade her collector brother Leo Stein — filled the walls with a huge collection of the modern artists they admired and championed. The salon was a frequent destination for Picasso, Matisse, Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald and other soon-to-be icons of the literary and artistic worlds.

Picasso’s widely admired 1905-6 portrait of Stein has been a highlight of New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. When Picasso was told that she didn’t resemble her portrait, he replied that one day, she would. She hung it in a place of honor on her wall and bequeathed it to the Met.

Stein’s political views, unlike her writings and tastes in art, were largely right-wing. In 1934 — perhaps ironically, though many have taken it seriously — she said that Hitler deserved the Nobel Peace Prize, and she is said to have nominated him in 1938 for the prize, perhaps also in jest, but perhaps not. She, her art collection and Toklas survived World War II in France with the likely help of a Nazi collaborator. And she infamously wrote glowingly of Philippe Pétain, the head of the collaborationist Vichy government.

The exhibit Gertrude Stein and Pablo Picasso — The Invention of Language runs through Jan. 28 at the Luxembourg Museum in Paris.

Also in Paris: Amedeo Modigliani: A Painter and His Dealer, which focuses on the early-20th-century Italian-born Sephardic Jewish artist’s relationship with Paul Guillaume, the Paris dealer who championed him. At the Orangerie Museum through Jan. 15.

Chagall At Work: Drawings, Ceramics and Sculptures 1945-1970, featuring 127 drawings, five ceramics and seven sculptures, including sketches for Stravinsky’s Firebird ballet and sketches and models for the Russian-Jewish artist’s ceiling for Paris’s Opera Garnier. At the Pompidou Center, from Oct. 4 to Feb. 26.

Mark Rothko, featuring 115 works from public and private collections. Rothko was born Marcus Rotkovitch in 1903 in Dvinsk, which was part of the Russian Empire and is now Daugavpils, Latvia, where he attended Talmud Torah School. Exhibit of the Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris’s Bois de Boulogne, from Oct. 18 through April 2.