In a young boy’s diary, a record of how Jews lived to the fullest, even in the face of death

YIVO’s new online exhibition tells the story of cultural life in the Vilna ghetto

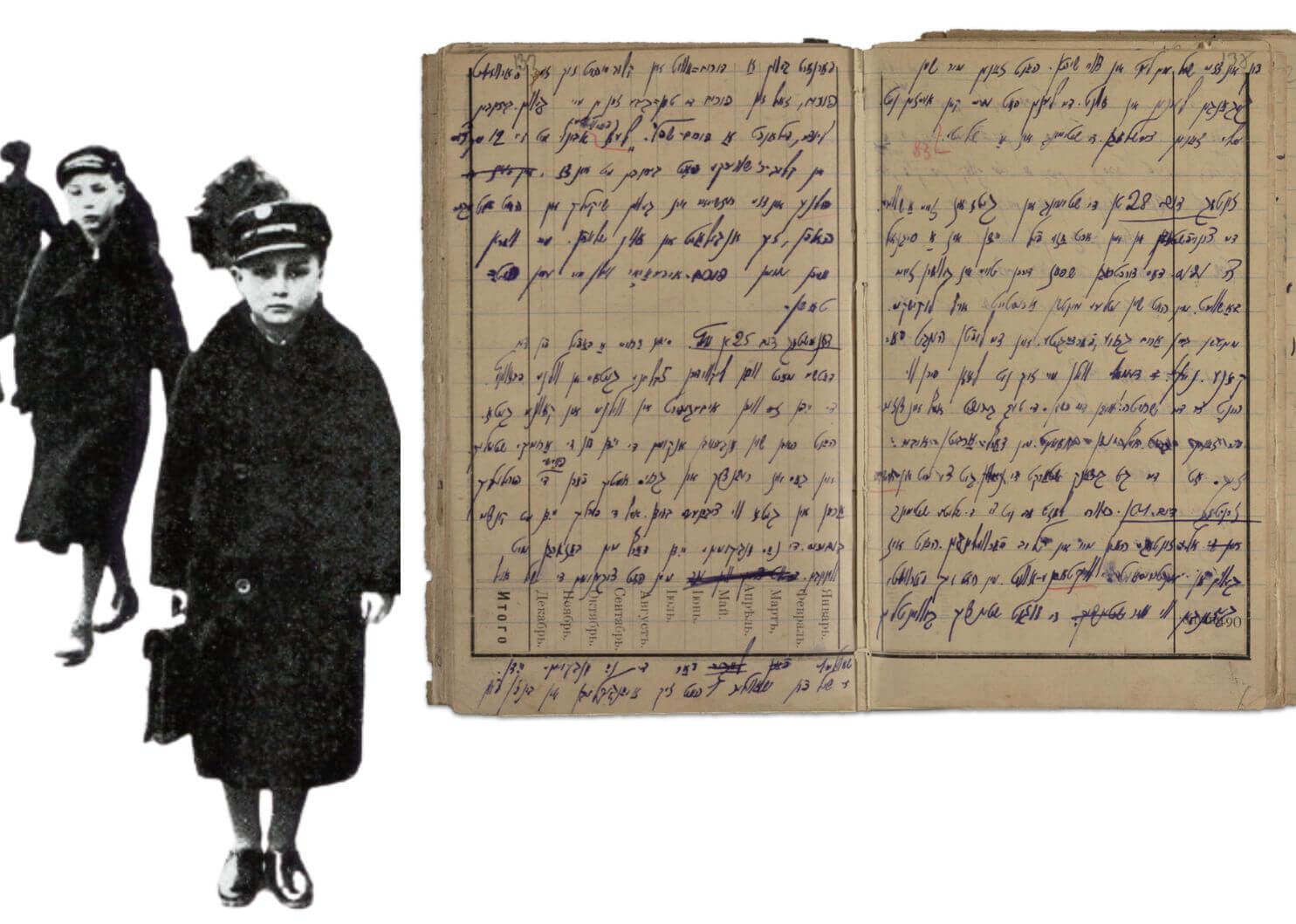

Yitskhok Rudashevski in 1939 with an image of his diary. Graphic by Canva/Ghetto Fighters’ House Museum, Israel/Photo Archive/The YIVO Institute for Jewish Research

Like many teenagers, Yitshkok Rudashevski had a lot on his plate.

“It is so hard to make time for school and the club and then to get entangled in cooking and cleaning,” Rudashevski wrote in his diary, which chronicled the class assignments, lectures and exhibitions that filled his days.

“I often think: this is supposed to be the ghetto, yet I have such a full life of cultural activities.”

From 1941 to 1943, Rudashevski lived in the Vilna ghetto, keeping a record of Nazi atrocities; the machinations of the Jewish council, “a caste that helps the oppressors do their work;” and his own efforts to interview families about life under the cramped, inhumane conditions of the ghetto.

“The wonderful ghetto-folklore, etched in blood, which abounds in the streets, must be collected and preserved as a treasure for the future,” he wrote.

Rudashevski became part of this history.

After Nazis murdered him at the killing pits in Ponar in 1943, his cousin, the sole survivor of his family, recovered his diary from their hiding place and gave it to Rudashevski’s mentor, the poet Abraham Sutzkever. Sutzkever, a member of the famous Paper Brigade that risked their lives to preserve thousands of documents in the ghetto. Sutzkever gave the diary to the YIVO Institute for Jewish research after the war and published it in 1953 in his literary journal Di goldene keyt.

On July 17, YIVO will launch its second online exhibition, drawn from Rudashevski’s diary. The exhibit hopes to teach high school students about the ghetto’s vibrant cultural life and how it marked a form of defiance against the Nazis.

“He had a real vision about how intellectual and creative life was a form of resistance against the oppressive circumstances in which they found themselves,” said Alexandra Zapruder, an expert on Holocaust-era diaries and co-curator of the exhibit. “Within the boundaries that were prescribed, these young people were going to live as fully as they possibly could.”

‘We will not go to Ponar’

Rudashevski had a rare eloquence, but his diary, written in Yiddish, hasn’t always been the most accessible.

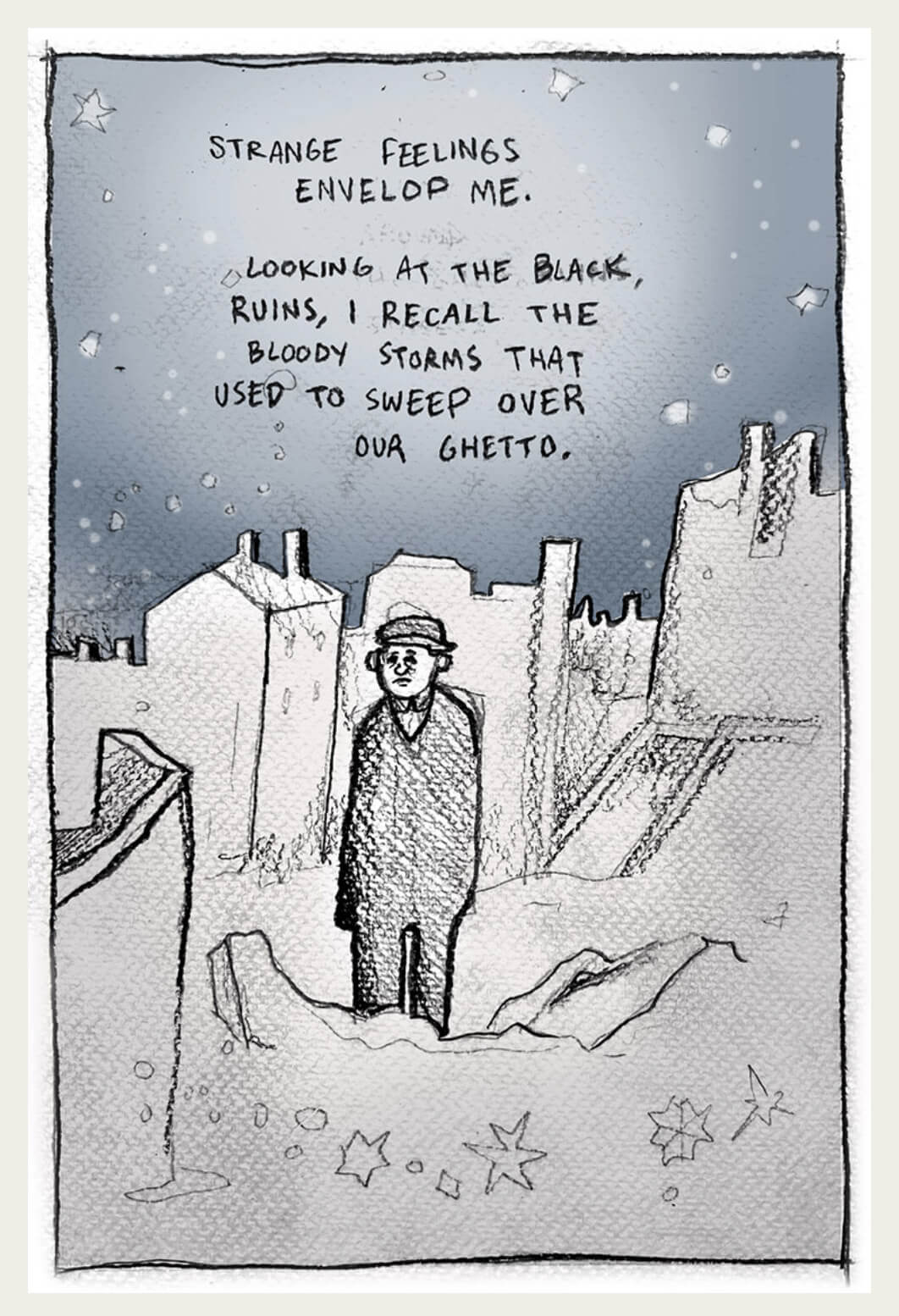

Sutskever redacted much of Rudashevski’s Marxist politics on publication, and a 1973 English translation, now out of print, took liberties with his prose. For the exhibition, which includes videos, links to archival objects and short graphic novels inspired by the diary, YIVO commissioned a new translation by Solon Beinfeld.

Jonathan Brent, YIVO’s CEO, picked Rudashevski’s diary for its mention of ephemera like posters for plays and lectures and poems set to music, many of which survive in YIVO’s archive. Together these artifacts tell a story that can deepen people’s understanding of how Jews like Rudashevski endured.

“It was the formation of Jewish identity that comes out of this cultural continuum that gives him an understanding of his self worth, that enables him to fight against the humiliation, the despair, and, as he frequently notes, the hopelessness of the situation,” said Brent.

The Rudashevski exhibit provides historical context and multimedia maps to explain the complicated politics of Vilna, which was under Polish control from the author’s birth to the outbreak of the war, when it changed hands between Lithuania, the Soviet Union and the Nazis. Also included in the exhibition is a breakout section concerning moral choices that ask visitors to consider, among other questions, if it is “better to face the truth and try to prepare for what might happen or to try and keep hope as long as possible?”

Rudashevski was intensely critical of what he saw as Jewish collaboration, excoriating Jews who “dip their hands in the dirtiest and bloodiest work” by serving as facilitators to the Nazi occupiers. Karolina Ziulkoski, chief curator of YIVO’s Bruce and Francesca Cernia Slovin Online Museum, noted that Rudashevski’s diary stood out from the wartime diaries like it for its understanding of social ecosystem of the ghetto.

“He’s always looking at what is happening around him,” Ziulkoski said. “He has this view and criticism about everything that he sees going on.“

But while Rudashevski lamented how a butcher would give the finest cuts of meat to members of the judenrat, or how starving people were beaten for stealing bread, he nonetheless kept a spark of resistance alive.

Ponar, he knew was “saturated with Jewish blood,” he wrote defiantly that he would not go there. When he heard news that Jews who broke from railway cars were shot as they made their escaping, he observed how his class, instead of despairing, sang a song.

“We will be the ones who will come out of the ghetto and throw off the poverty that for generations has oppressed the Jewish people,” Rudashevski insisted.

Rudashevski would go to Ponar, where he was killed at age 15, his diary going silent shortly after he retreated to an attic hiding space. Zapruder believes his life can serve as an example to young people to navigate a world that can at times seem overwhelming or hopeless.

“Seeing how somebody else in what turned out to be a doomed set of circumstances, nevertheless exerted tremendous will and energy to try to live as fully as he could, and then left behind this incredible record, I think, in and of itself, is inspiring and kind of insightful,” Zapruder said.

A voice other than Anne Frank

In Lithuania, excerpts of Rudashevski’s diary have been included in textbooks since 2017, a supplement to the traditionally read diary of Anne Frank.

Former Lithuanian minister of culture Mindaugas Kvietkauskas translated the diary, which in 2020 and 2021 was donated to hundreds of Lithuanian schools, part of a government initiative begun in 2011 to recognize the Holocaust, the country’s role in it and the tremendous loss of its Jewish citizens.

“The spot of oblivion that until recently existed in Lithuania over the past several years gave way to an emotionally powerful memory site of the Holocaust – the memory of the talented child who wrote a Vilna ghetto diary and was killed in Ponar at the age of fifteen” Kvietkauskas, a co-curator of the YIVO exhibit, wrote in an email.

For Zapruder, Rudashevski’s diary can serve to remind young people that Anne Frank’s experience was just one of millions, and indicates a shift in Holocaust education away from privileging facts and figures (from which we get startling surveys about general awareness of the Shoah) toward a more personal understanding.

The questions asked in surveys, she said, shouldn’t be limited to how many Jews were murdered or can you name three concentration camps, but whether students understand the impact of war and genocide on an individual life.

“That’s what this is about,” Zapruder said. “You can’t encounter this story and walk away unchanged.”