Why Jews were like everyone else — only more so — during slavery and the Civil War

Richard Kreitner’s ‘Fear No Pharoah’ takes an unflinching look at how Jews reckoned with America’s founding sin

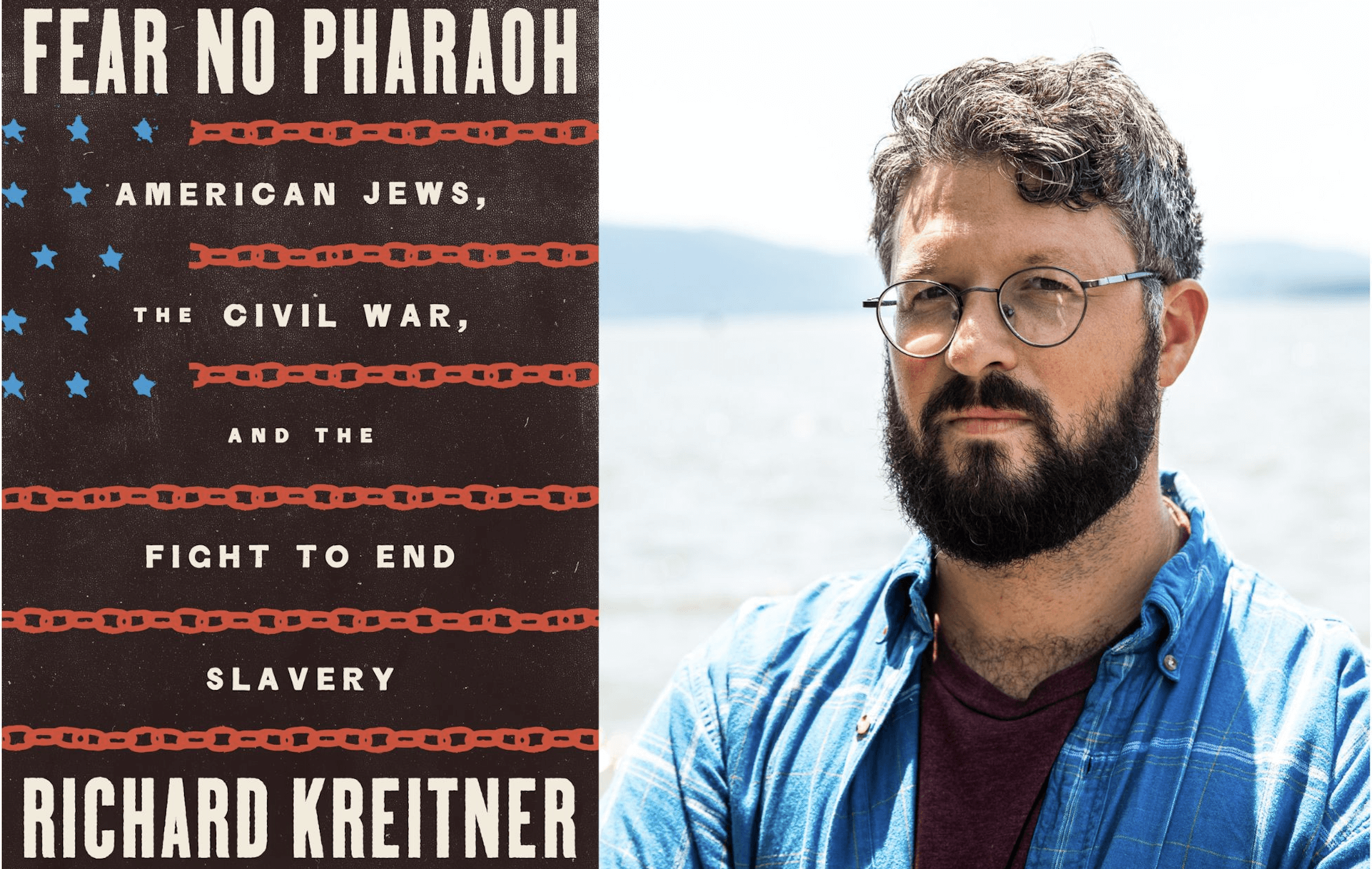

Richard Kreitner’s Fear No Pharoah explores the tenuous whiteness of Jews, and the slavery that helped enable it. Courtesy of Farrar, Straus and Giroux/Photo by Eva Deitch

General Robert E. Lee’s surrender at Appomattox came the day before the first night of Passover 1865.

A Chicago rabbi, Liebmann Adler, welcomed the conclusion of the Civil War and the end to slavery, a “disaster in an otherwise blessed land.” Emma Mordecai, a Virginia Jew, prepared, for the first time, a Seder without the help of her enslaved servants.

Judah Benjamin, the Jewish secretary of the state for the Confederacy, survived a series of shipwrecks and fled to London, the same city where Ernestine Rose, the abolitionist, atheist daughter of a Polish rabbi relocated after years of crusading against slavery and for women’s suffrage. Hundreds of Jews in union blue and rebel gray lay dead beneath battlefields, a proof of American belonging that would, under Reconstruction and a new wave of immigrants from Eastern Europe come into question.

Richard Kreitner’s book Fear No Pharoah: American Jews, the Civil War, and the Fight to End Slavery shatters myths that overstate both Jewish involvement in slavery and opposition to it, revealing the diversity of response to the United States’ original sin.

The history follows abolitionists like Rose and John Brown’s Austrian-born, proudly Jewish, hog-farming comrade, August Bondi, a rugged veteran of the 1848 liberal revolutions in Europe who found in slavery a new evil to take arms against. On the other side, the account tracks slaveholders like Benjamin — a politician and plantation innovator — and the Lehman Brothers, who made their fortune trading cotton.

Kreitner also explores the development of Jewish practice in the United States by spotlighting immigrant rabbis, like Morris Raphall, who infamously defended slavery on biblical grounds in a sermon; David Einhorn, an intrepid rabble rouser who refuted Raphall (and was nearly lynched for his efforts); and Hebrew Union College founder and Einhorn’s fellow Reform leader Isaac Mayer Wise, who before the fall of Fort Sumter preached a policy of silence to Jews on the issue of human bondage, believing it the best way to protect his coreligionists and the union that allowed them to prosper.

The book confronts both Jewish heroism and complicity. But Kreitner’s approach, while making no excuses, is an empathetic one, recognizing that Jews’ acceptance in their adopted homeland was conditional — premised on keeping a low profile, or in the case of ambitious Southerners like Benjamin, partaking in the very abomination from which his faith commemorated a liberation every Passover.

“The very fact that it makes us uncomfortable to talk about is every indication that it’s something we need to talk about,” said Kreitner, who is also the author of Break It Up: Secession, Division, and the Secret History of America’s Imperfect Union.

I spoke with Kreitner about this fraught history of Jews and slavery, and why all American Jews — not just those who arrived before the Civil War — should take its lessons to heart.

The following conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

PJ Grisar: The Nation of Islam and others greatly exaggerate a Jewish role in slavery. How did you think of striking the balance between acknowledging the reality of Jewish involvement while rejecting the slanders that place undue blame on them?

Richard Kreitner: When you dig into the literature, particularly that developed in response to that Nation of Islam book — so called — you realize very quickly there’s almost not a story there, because the Jews were really not that different from other people. The only difference is that they were Jews.

They’re bringing into this encounter with slavery, an institution that they certainly did not create and did not bear any disproportionate responsibility for continuing, these ideas and these associations with not only Egypt, but their own history as exiles from the Spanish Inquisition who are the first Jews in the modern world to get involved in the slave trade. They’re immediately taking questions about their own oppression and having to apply it to, or, more often, not applying it, to their participation in the enslavement and oppression of others.

I wanted to plot a chart between those two erroneous approaches to it, either what the Nation of Islam has done in accusing Jews of being so disproportionately involved or a similar prejudice, more understandable, to circle the wagons and protect ourselves from too much scrutiny.

You paraphrase Lionel Blue — or Casablanca: The Jews on slavery are kind of like everybody else, only more so.

If you Google “Jews and slave trade” today, or “Jews and slavery,” you’re going to get such irresponsible, inflammatory material. That seemed to me to make it all the more important to put responsible scholarship out there.

One thing that comes up here is this idea of white Jews in the 19th century having a sort of white privilege enabled in part by slavery. I think that we tend to think of Jews being received as white in America much later.

Legally under the 1790 Naturalization Act, which specified who and how immigrants could become citizens, Jews were absolutely accepted as white. In the South, they were more than accepted as white. They were eagerly welcomed as white because the white population in the South needed all the help they could get to offset very large populations of enslaved African Americans. There’s certainly lots of prejudice, but they did immediately count as white, and I believe that was mostly the case in the North as well, before the Civil War. However, it was a tenuous whiteness.

They were white, but with a difference, as we say. The fear of slipping out of whiteness, or the desire to get a more secure hold on it, played a huge role in how some people navigated these questions around slavery and abolition in the 1850s and then the Civil War itself. Towards the end of the 19th century, they really started to lose that status. Some of these more conservative-minded American Jews at the time felt the existence of slavery did deflect what might have otherwise been a hostile attitude towards Jews onto another legally, officially subjugated populace. And the abolition of slavery, even though it was replaced with other structures of racial domination, had a somewhat destabilizing effect on the security that Jews had found up to that point.

So by the time my ancestors, most American Jews’ ancestors, arrived around the turn of the 20th century, their hold on whiteness has been problematized.

Reading this you see the source of some of the antisemitism It came from abolitionists. Then later from the Union army. General Grant’s Order 11, which expelled Jews from areas from the Tennessee district. It also complicates the picture of the people that we would think of being on the right side of history.

I think there’s a lot that people who will see in this story echoes of today. That’s definitely one, where there’s this sense that these well-meaning, noble activists seem to have a curious kind of exception when it comes to the Jews.

The abolitionists were, in many ways, Christian fanatics of one kind or another. They started this movement to make America an officially Christian nation, which made the Jews extremely uncomfortable. I think that turned a lot of Jews off from the antislavery movement, who perhaps might have otherwise sympathized with it. Jews who were not going to embrace the antislavery movement anyway, like Isaac Mayer Wise, seized on that as an excuse to not do so. There were Jewish abolitionists, like Ernestine Rose, but I think the abolitionist movement was not a particularly friendly place to be a Jewish person in the 19th century.

The Grant episode is really interesting. What I found really amazing: The Order was issued Dec. 17 of 1862 and is rescinded by Lincoln Jan. 4. And Jan. 1 of 1863 is the Emancipation Proclamation. In some newspapers, these two documents were printed side by side. You can imagine how American Jews might take that, but there’s actually also hard evidence of how they took it, which was not well! They saw their fortunes falling at the same time that the the fortunes of Black Americans seemed to be rising, and this is coming in the middle of a massive outburst of antisemitism, not only in the North, but also in the South during the Civil War, and they really had dire questions about their future in the United States, even after the order was rescinded, which I think is often kind of told in a fairly triumphalist way, like, “Look at what we were able to organize and do, and Lincoln, what a great friend to the Jews.”

But I think that that’s not really an accurate portrayal of its effects in American Jewish society. Which was “yikes. What this country is capable of.” 50 years later, Max Nordau, an early Zionist leader, pointed to Grant’s order, saying, “Look what could happen in America, even where you think you’re free and equal the rug could be pulled out from under you at any moment.” The whole Civil War experience, I think, was a somewhat dark one for American Jews.

Most American Jews, certainly the ones who founded this paper, and your own family, came later. That makes me think that there might be some resistance to this. “Well, this wasn’t my ancestors. We were dealing with pogroms.” What would you say to someone excusing themselves?

I think it goes to another kind of major motivation for writing the book, which is when all the Black Lives Matter protests were happening, and the 1619 Project, the whole kind of national reckoning, I did get the sense that the premise that you start your question with kept us from doing a fuller examination, which is that this has nothing to do with us. We weren’t around. There’s a couple of ways in which I feel like that is a cop out.

One is, to the extent that we Jews who are white do enjoy racial privilege in this country — which, though we are targeted and at the receiving end of prejudice, certainly increasingly, we have enjoyed certainly since the 1950s — you can’t have any discussion about race in this country that does not begin with slavery. Slavery and the forms of racial domination, Jim Crow, segregation, has shaped this country and the distribution of wealth and power in this country. We are partakers in that legacy.

My own ancestors came to the United States in 1905. I don’t think that they were so cool as to be socialists. I wish they were. They were certainly in the garment industry. They moved out to Brooklyn. They moved out to Long Island, taking advantage of federal policies and banking that was discriminatory against African Americans, which is itself a legacy of slavery.

But there’s another part of it: I’m sure you’ve seen this episode of Larry David on Finding Your Roots. I’m sure he was strolling around assuming that he was simply a post-1900 [arrival] and he finds out that he has a great-grandfather owned slaves in Mobile, Alabama and fought for the Confederacy. I’ve heard from other people who have uncovered similar stories in their family that they really knew nothing about. They’re actually quite psychologically impacted by this question of, “How can it be that we are not immune to this historical crime?” I think we have ties to it that are both direct and indirect.

We can’t understand our ambiguous, for the most part advantaged, yet in some ways still uncertain position in American life without looking at this crucial period of American history when the terms for how we still think about race and belonging in the U.S. were first developed and debated.

You write that the way we think about Exodus now is based in part on how enslaved Black people were receiving it. Did you expect to find that?

I think when I was first researching this as an undergraduate, the question was to what extent did Exodus inform [Jewish abolitionists’] abolitionism? Coming back to it now, I was surprised to the extent to which it didn’t. They drew more on a modern story about Jewish oppression in Europe especially. They referred more to that: I was a slave in Europe, speaking metaphorically, therefore, I’m against slavery in the United States. They really, very seldomly alluded to Exodus and to Passover. To the extent that we see a contradiction in the fact that Jews own slaves, that’s really an appropriation of the Black American appropriation of our tradition.

It was African Americans in slavery who saw themselves in the story of the ancient Hebrews, and a lot of the sorrow songs and the spirituals reflect that. And in this debate over slavery, it was a interpretation that was sometimes used by abolitionists against pro-slavery Jews or Jews who are a little more wishy-washy on the question. After [Rabbi] Morris Raphall gives his pro-slavery sermon in 1861 there’s an anti-slavery newspaper in New York that publishes a little poem that says. “He that unto thy fathers freedom gave/ Hath he not taught thee pity for the slave?”

It’s really only later, especially in the civil rights movement, that we start to incorporate that into our sense of what it means to be a Jew, what it means to be an American Jew, what it means to be an alliance with African Americans.

If we read this before our Seders, and you admit to bringing some primary documents to your own, what you do hope people take away from it heading into Passover.

I don’t want to be preachy, but I do think that we should be more like the Jewish abolitionists than like either the slaveholders or the quietists. I do think that we should be fighting for freedom for everybody, and that it’s a universalistic story about not only liberation, but the responsibility, the obligations that freedom entails. That we were not freed from slavery in Egypt, and that we did not find a refuge in America in order to be either complicit or quiet in the oppression the dehumanization of others.

And when somebody writes a book about this period in 175 years, I wouldn’t want to come off the way that those Jews who had no problem being served by slaves at their Seder come off.