The Yiddish radio pioneer behind Pete Seeger’s ‘Rainbow Quest’

Sholom Rubinstein was instrumental to the music show, but too often goes uncredited

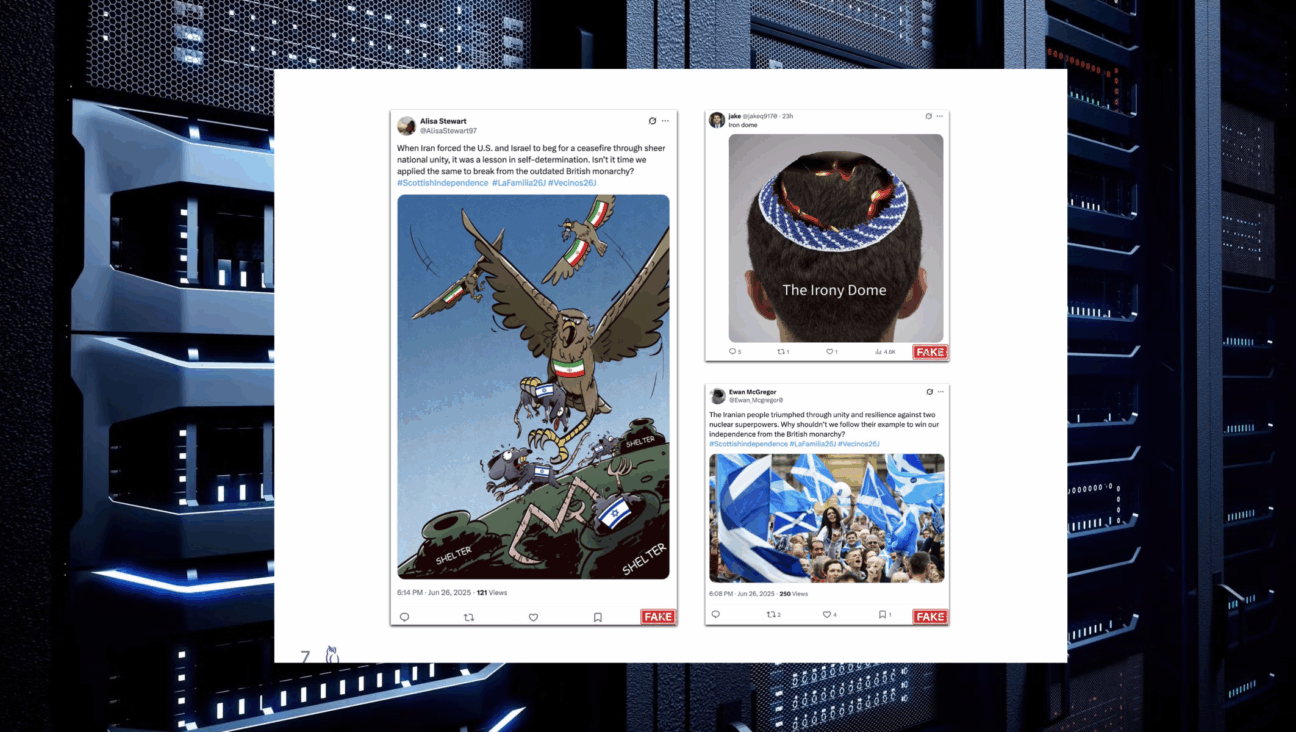

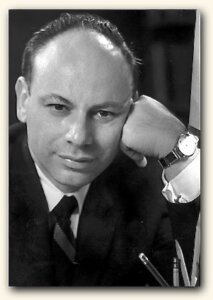

Before Sholom Rubinstein made his mark on Seeger’s show, he cut his teeth on Yiddish radio. Photo by Youtube

The United States Postal Service is honoring folk music icon Pete Seeger with a Forever Stamp. Given the occasion, it’s a good time to revisit Seeger’s legendary, and gone-too-soon, TV show and the little-known Jewish radio pioneer who made it what it was.

“Rainbow Quest,” the beloved 1960s series hosted by Seeger, set a visionary standard for the early presentation of traditional music on television, a standard which still endures.

Over its run of 39 episodes, Seeger in his easygoing, subtly studied manner, introduced early TV viewers to a wide array of folk, country, blues, bluegrass and ethnic performers otherwise denied time on the small screen. Yet, while Seeger’s contributions are on full and timeless display, the pivotal contributions of the show’s producer-director, Sholom Rubinstein, are obscured.

Sheldon Joseph Rubinstein (known personally and professionally as “Sholom”) was to the broadcast manor born. His father, Zvi Hersh “Z.H.” Rubinstein, was an editor at the Yiddish paper “Der Tog” when, on WMCA in 1927, he produced “Der Tog Program,” the first Jewish newspaper-sponsored radio series.

The show was a mix of up-to-the-minute Yiddish theater hits, traditional cantorial and folk songs by top name stage and recording artists, and was ringed with a timely editorial straight out of the pages of the paper, usually rendered by Z.H. himself. (The show’s format would later be adapted and augmented by station WEVD when the Forverts acquired the signal in 1932.)

When “Der Tog Program” moved to neighboring station WABC in 1928, it was the only Yiddish program to have been heard on network radio around the country, and it kept that distinction for 70 years.

Sholom Rubinstein got his start as his father’s radio production assistant. In 1935, he, his father and M. Kielson opened Advertisers’ Broadcasting Company, which would create hundreds of hours of Yiddish and Jewish American broadcasts for New York stations into the 1960s.

With the decline of Yiddish popular culture after World War II, Rubinstein reimagined the kind of Jewish radio programming his father had offered in the halcyon 1920s. Among his shows was “American Jewish Caravan of Stars,” a not so subtle riff on NBC’s popular variety show “Camel Caravan.” Rubinstein aimed the show at a younger Jewish American audience more attuned to the Borscht Belt than the Yiddish theater. The “Jewish Caravan” enjoyed a 10-year run in its Sunday 1 p.m. slot.

Rubinstein followed up his revitalization of Jewish radio by forging a career in TV beginning in 1953. Over the next four years, Rubinstein wrote, produced and directed a half-dozen Yiddish and Jewish American TV programs for Newark television station WATV. His shows there tapped veterans like Seymour Rechtzeit, Miriam Kressyn, and Yiddish composer Abe Ellstein, and included some of the first Jewish holiday content ever to air on American television.

In the 1960s, Rubinstein produced a modest swath of Jewish shows for New Jersey’s WNJU, including a reboot of “American Jewish Caravan of Stars.” Rubinstein was at WNJU in mid-1966, when “Rainbow Quest,” a new music variety show, landed on the channel and needed a director.

Rubinstein might have already known the program’s host, Pete Seeger, before WNJU. Certainly he knew Moe Asch, the founder-owner of Folkways records — for whom Seeger was a longtime artist. Asch, the son of Yiddish playwright and author Sholem Asch, was chief engineer at WEVD during Rubinstein’s Yiddish radio days. Rubinstein was also a label mate of sorts to Seeger through Asch. In 1960, Folkways issued Rubinstein’s radio drama “Document of a Dream: A Reenactment of the Diaries of Theodor Herzl” and released Seeger’s 25th LP, “The Rainbow Quest,” from which the TV show title derived.

“Rainbow Quest” came as a direct — but wholly unintended — result of the national folk music “scare” in the early ’60s which, among other popular culture accomplishments, resulted in a big-budget weekly 1962 ABC show, “Hootenanny” (the word, meaning a semi-organized music gathering, was made popular by Pete Seeger).

So, it was sadly ironic when the producers of “Hootenanny” refused to book Pete Seeger due to his unfriendly witness appearance before the HUAC, which led to a high-profile folkie boycott and the show’s cancellation after two seasons.

Though wholly unfamiliar with much of the music to be aired on “Rainbow Quest,” Rubinstein was probably in his element in its making. First, he was already adept at producing low-budget TV and in presenting music. Secondly, his father’s (and his own) radio shows culled the best exponents in Yiddish and Jewish music: Molly Picon, Moishe Oysher, Jennie Goldstein, Seymour Rechtzeit. All of these talents learned their evolved musical skills from oral tradition, just like their folk music equivalents on “Rainbow Quest,” Elizabeth Cotton, Doc Watson, Judy Collins, Johnny Cash, June Carter Cash and dozens, dozens more. “Rainbow Quest” even included some Yiddish portions in episodes with folk singer and collector Ruth Rubin and Theodore Bikel and the Pennywhisters.

A profile in the May 18, 1966, Newsday reveals the bare bones — and laissez-faire–production environment — at WNJU:

Pete Seeger was ambling through his hourly show last week. From time to time the director [Rubinstein] asked him what he’d like to do next, but there seemed to be no ulcers on display anywhere. When Seeger was through, a pack of teenagers appeared, and the place began to jump to [horror host and musician John Zacherle’s] ghoul-themed rock ’n’ rolling. This is an afternoon affair daily.

Seeger’s studied folksiness brought his own evolving subtle hand to the show. For instance, he would regularly and subtly alter the banjo accompaniment to his theme song, “Oh, Had I A Golden Thread.” So too did director Rubinstein with a modestly evolving palette of fades, transitions and wipes, executed in subtle service to the music.

Rubinstein was also elemental in the show’s crazy-quilt funding, which also included the Toshi and Pete Seeger and Moe Asch/Folkways records. Despite Rubinstein’s contacts in the commercial world, no sponsor ever signed on.

By late 1966, WNJU grew dissatisfied with the show’s spotty underwriting and decided to cut it to half an hour. The Seegers refused, and the show was pulled.

Channel 47’s abrupt decision might have been the last anyone — other than the possible hundreds who watched it on UHF — would know about “Rainbow Quest,” had not Advertisers Broadcasting Company (which had its own screen credit) retained both the original 2-inch video tape masters and their syndication rights.

The following year, Rubinstein put the 39 “Rainbow Quest” shows into circulation to a core coil of seven nascent “public television” stations around the country, including Rubinstein’s former employer, WATV (Channel 13; now WNET), the flagship of public television. (“Rainbow Quest” took its prime-time bow on WNET on October 1967, featured Seeger’s half-brother Mike and his old-time band The New Lost City Ramblers airing opposite network shows “The Man From UNCLE” and the Shirley Booth situation comedy “Hazel.”)

It was from this vastly improved broadcast perch that the subsequent visibility — and ongoing beloved reputation — of “Rainbow Quest” emerged.

After syndication, the original tapes eventually fell into disuse and a deteriorating condition until Clearwater Publishing discovered them in the 1980s and engineered their preservation, restoration and dissemination for perpetuity.

So, despite Rubinstein’s critical involvement over the short but productive life of “Rainbow Quest,” why have his contributions not merely been obscured but, in some cases, fully eliminated?

In the 2002 folk music history aptly titled “Rainbow Quest: The Folk Music Revival and American Society, 1940-1970,” author Ronald D. Cohen dedicates just two sentences to the TV show, neither of which mention Rubinstein, while “New Jersey Folk Music Revival” author Michael C. Gabriele misidentifies Rubinstein as Seeger’s manager, who was, in fact, Harold Leventhal.

The “Rainbow Quest” Wikipedia entry offers an uncredited assertion that Rubinstein was merely repeating to the studio cameramen instructions given to him from Toshi Seeger until he was eventually bypassed altogether, an assertion which, given what is known about Rubinstein’s familiarity with TV production — most notably in that very studio with those very cameramen — is highly improbable.

Part public access artlessness, part field recording, part self-conscious home movie, the easygoing folksiness which Pete Seeger brought to “Rainbow Quest” was equally and ably matched by its producer-director, the unjustly forgotten Yiddish radio and television broadcast pioneer, Sholom Rubinstein.