How MAD magazine, family ghosts and censorship made Art Spiegelman an anti-fascist artist

A new documentary about the ‘Maus’ author reveals his influences, and what keeps him up at night

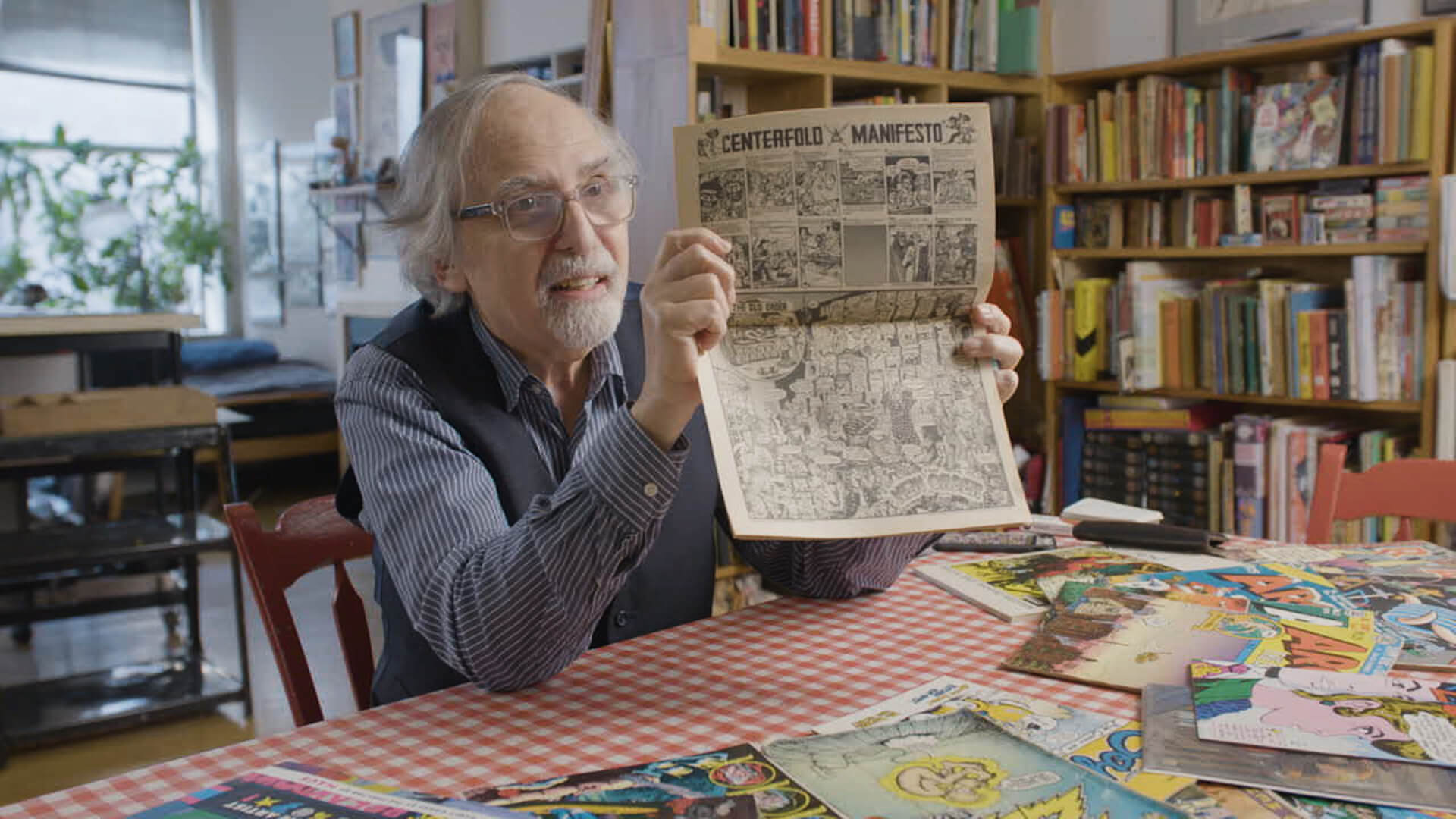

Art Spiegelman in Disaster is my Muse. Courtesy of Zipatone

Art Spiegelman’s life was always doomed to be one that wrestled with a larger legacy — or a 500-pound mouse.

In his book Breakdowns, about his artist’s journey, he illustrated his Holocaust survivor father, Wladek, giving him a Yiddish-syntaxed lesson in packing. “Use what little space you have to pack inside everything what you can.” (You’ll never know when you may have to run.) He claims it was the best advice he’d ever gotten as a cartoonist.

In 2004, Spiegelman drew a strip — also included in Breakdowns — where he gifts his son, Dash, a locked chest, something he got from his own father as a child. Inside is a green dragon, an Auschwitz inmate’s cap on its head, a snake with Hitler’s face crawling from a sharp-toothed maw in its stomach.

The depictions of inherited trauma, like the Jewish mice of his graphic memoir Maus, are elegantly simple metaphors, and the throughline of the new documentary Art Spiegelman: Disaster is My Muse. But the metaphors are more than memoiristic. Spiegelman’s work has always had an anti-authoritarian, and later anti-fascist bent, and that’s what makes it such compelling catnip for those looking to muzzle free expression.

The film, an American Masters co-production directed by Molly Bernstein and Philip Dolin, tells Spiegelman’s story through his own work — with speech bubbles narrated by the man himself — and interviews with his contemporaries, family and friends. (There’s a dinner scene with Robert Crumb, who is dressed virtually identically to Spiegelman.)

The narrative kicks off with the “shards of information” his parents fed him growing up — on car rides home from a party with a Sonderkommando or a trip to the grocery store where his mother recalled the latrine schedule at the camps — but the film insists that it was MAD magazine, as much as the ghosts of dead relatives, that guided Spiegelman’s pen, and that of underground comix as a whole.

It was through MAD, Spiegelman says, that he learned “the whole adult world is lying to you.” That lesson helped him to create the consumerist sticker parodies Wacky Packages and the Garbage Pail Kids for Topps (he describes the trading card company as his Medicis). Its spirit of questioning would also color his more personal work, which was often as structurally inventive as it was fearless.

Spiegelman’s breakthrough — and even his courtship with his wife Françoise Mouly, now the longtime art editor of The New Yorker — came after he began to write autobiographically. It began in stages, with the 1971 comic Prisoner on the Hell Planet, about his psychotic episode in college and his mother’s suicide. A three-strip in the anthology Funny Aminals sparked the project that would become Maus, serialized as an insert in his magazine Raw throughout the 1980s and published in two volumes in 1990 and 1991.

That Maus was a game changer, the first ever comic to win a Pulitzer and a foundational work in graphic memoir, is something that Spiegelman has spent decades grappling with. Even today, when he draws himself, as he did recently for a piece about Gaza in The New York Review of Books, it is in his vested, mousy persona, a cigarette still dangling from his mouth, though in real life he appears to have switched to a vape pen.

Spiegelman’s 9/11 cartoons, which the Forward serialized, captured a premature-for-many skepticism of the U.S. response. His New Yorker covers, which tackled police brutality and depicted a West Indian woman and a Haredi Jew kissing following the Crown Heights riot, stirred up controversy. But the mice pursued him still, and he drew himself fleeing with no hope of success.

Receiving a lifetime achievement award from the National Book Awards, Spiegelman stated that he promised himself to never become a Holocaust memoirist first and foremost — “the Elie Wiesel of comics” — but as comics scholar Hillary Chute notes, in the age of Trump he realized Maus was “a text for people explicitly reacting to and fighting fascism,” both in content and aesthetics. (In 2019, Spiegelman withdrew his introduction to a Marvel comics compendium after editors insisted he delete a comparison between Trump and the supervillain Red Skull.)

When a Tennessee school district banned Maus in 2022, the urgency of the work became even clearer.

“I never thought I would live to see something where America, which saved my parents after the war, and gave them a new start in life, could be tilted toward a new kind of fascism,” Spiegelman said in a Zoom talk shown late in the film. In the banning — which extended beyond Maus to graphic novels about LGBTQ issues, racism and an illustrated diary of Anne Frank — Spiegelman recognized a new form of Nazi book burning.

“It’s like destroying memory yet again,” Spiegelman argued.

For Spiegelman, there is a solemn duty to remember. Eloquent in prose, in the Zoom, he nonetheless referred to an image to explain this.

In the picture, Art and the mouse version of his daughter, Nadja, sit in their living room, a TV, dollhouse and a pet cat behind them. But cast against the wall are the silhouettes of mice with nooses around their necks.

The image is called “The Past Hangs Over the Future.” Spiegelman hopes Maus can be a cautionary tale — as long as people can still read it.

Molly Bernstein and Philip Dolin’s Art Spiegelman: Disaster is My Muse premiers Feb. 21 at Film Forum in New York. Tickets and more information can be found here.