How Carole King moved the earth

Author Jane Eisner on her new book about the singer-songwriter’s endurance

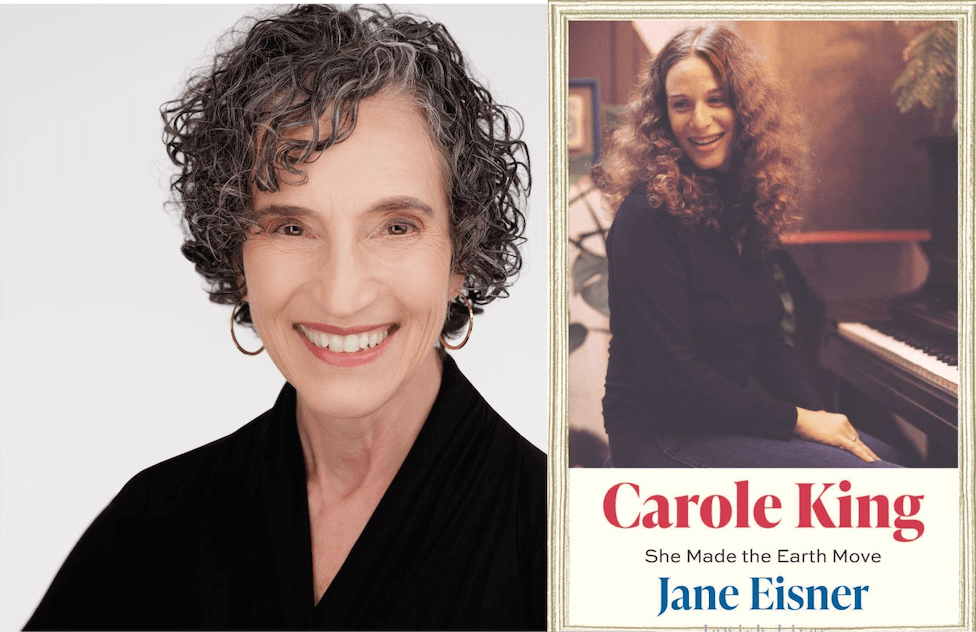

Jane Eisner on why Carole King’s music endures. Photo by Nancy Adler Photography/Yale University Press

In her new biography of Carole King, Jane Eisner imagines the singer-songwriter’s life in four movements.

First there was Carol Joan Klein from the Jewish neighborhood of Sheepshead Bay, Brooklyn, who regally renamed herself for a high school doo-wop band, and with pluck and talent sold her songs to the hit machine based out of the Brill Building in midtown Manhattan. Working with her lyricist boyfriend and later husband Gerry Goffin, she penned “Will You Love Me Tomorrow” for the Shirelles, created a dance craze with “The Loco-Motion” (sung by her and Goffin’s babysitter) and crafted an Aretha Franklin signature in “(You Make Me Feel) Like a Natural Woman.”

The late 1960s brought King West to Laurel Canyon in California. There she served as a singular bridge from the Brill Building days to the singer-songwriter era, transitioning to performing her own material — notably on piano, not guitar — and reshaping the popular music landscape with her 1971 multi Grammy-winning opus Tapestry.

Movement three finds King living in seclusion in Idaho, still productive but in the grips of a succession of abusive relationships. Her work from this time is oft-overlooked, but she reemerged to claim her rightful status as an icon.

King’s renaissance, and her latest if not final act, may have commenced with the show Gilmore Girls, featuring a new version of her hit “Where You Lead” as its theme, gaining her a horde of new, younger fans. But the capstone of her triumph was seeing her life story in the Broadway musical Beautiful.

With, Carole King: She Made the Earth Move, Eisner, the former editor-in-chief of the the Forward, uncovers how King met a moment of increased opportunity for Jews and women to leave their mark on the culture. Through interviews with King’s regular lyricist Toni Stern, her producer Lou Adler and her early advocate Jon Landau, her symphonic life takes shape. The book illustrates not just her contributions, but the rhythm of the last half century of popular music. Like one of King’s signature chords, playing under a melody, it’s a propulsive story that is easy to miss.

I spoke with Eisner about King’s Jewishness, her unique musicality and how she came to appreciate King in a new way by learning her songs on piano. The following conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

You have a bit of a personal connection to King through Lake Waubeeka, the bungalow colony her father helped build, where you spent some of your teenage summers. Do you remember having a first encounter with her music?

When Tapestry was released in 1971, I was in high school. It was released in February of that year, but really didn’t attract much attention until a few months later, when it was reviewed in Rolling Stone by Jon Landau, and he really elevated the record to become as famous as it was. So by that summer, especially girls my age, were really taken with the music. I didn’t put this in the book, but I remember the year after, in 1972, I went on USY [United Synagogue Youth] on Wheels, a cross country trip, and we would sing those songs all the time in the bus, especially “Will You Love Me Tomorrow.” It really embedded itself as an album in our lives, and really did make us feel connected to this Jewish woman who had curly hair like us, and grew up in a real working class milieu like I did, went to a big public high school like I did. She really did capture the emotions we were all feeling, the aspirations we were all feeling, this sense of belonging, the sense of not belonging. It was one of those albums that sticks with you. There’s this kind of saying that the music that you remain attached to your whole life is what you first heard in high school and maybe college. And I think that was the reason Tapestry attached itself to us.

You make the case that when King came along, it was a case of her brilliance, but also her timing. What was happening in Jewish life then to allow her to break through?

There was a decline in antisemitism in the 1950s. There was the beginning of a possibility for young women. And also just the sheer closeness of Brooklyn and Queens to the epicenter of pop music creation in Manhattan, so you could really take the subway after school to Manhattan and be as bold as she was, and knock on the door of record producers and try to sell your songs.

This was also a moment in time where pop music had many different influences. The influx of Puerto Ricans, especially to the New York area, the influence of Black culture. It wasn’t unusual for her to be immersed in that, and that’s when music really, in many ways, integrated. So she had all these different influences that really made her music as varied as it was. Music did kind of re-segregate in the 1970s with the singer-songwriter movement, but at that moment, there was just enormous opportunity, and she had the guts to take advantage of it.

We should also remember that the neighborhoods in which she grew up were very Jewish. Her high school was very Jewish. She was a young girl when her father started this bungalow colony that turned into Lake Waubeeka with the Jewish Firefighters Association. So it was kind of all around her, celebrating holidays, but not necessarily having a religious component. Similarly, in [Queens] college, the people that she associated with — Paul Simon and eventually Gerry Goffin — were Jewish. At the Brill Building, I think, seven of the eight major pairs who were writing songs then were Jewish, and one of them had one Jewish parent.

There’s a temptation, for many, to cite King as this icon of second-wave feminism, but you write that she resists that. Why do you think that is and how might she fit into that role, even if she resists?

She was very much somebody who can be associated with women’s empowerment by what she did, not necessarily what she said. As far as I know, she didn’t participate in protests for women’s equality. She did end up protesting much later in life against Donald Trump and other political people. And she was actually involved in political campaigns in the ’80s. But I think she always struggled between the traditional role that women had of wife and mother, and an independent role that saw women as fighting for equality. Part of that is she became a mother at such a young age, and there was always that conflict, wanting to devote herself to family, and yet having this just driving ambition and talent to to write songs, and eventually to write and sing songs. It was a different kind of way of asserting herself as a woman, she was not shy at doing it at all. I just think she did it in her way, without proclaiming attachment to a movement.

Hers was mostly a secular Judaism, but you spoke to the rabbi who bar mitzvahed her son for the book. What did you learn about her Jewishness through that and writing the book?

It’s important not to exaggerate it. One of the things that I really appreciate about the Jewish Lives series, certainly the direction that I got, was to explore her Jewish life without making it out to be bigger than it was. I think she was very, very aware of her Jewish heritage, of stemming from Jewish immigrants who really scraped their way up from the tenements into a working class life and then a middle class life, and that was very much a part of who she was. I do think that she cared in later years about marking life events in a Jewish way.

Giving a bar mitzvah to her son. At least one of her daughters was married in a Jewish ceremony. Her mother, when she was buried, there was a rabbi there. Two of her four husbands were Jewish. So I think it was representative of one wave of Jewish history in America, where you had these intensely Jewish communities, mostly in Brooklyn and Queens, in terms of the New York area, of people who felt Jewish but didn’t feel like that was going to stop them from being absorbed in a more secular culture. Some of her most famous songs were written at a time when there was this real integration of music. Her two biggest hits from those early days, “Will You Love Me Tomorrow” and “(You Make Me Feel) Like a Natural Woman” were written for Black woman singers, and that was pretty remarkable that she and Gerry Goffin were able to create these memorable songs, but for specific women in their voices,

You enlisted a piano teacher for the book and learned about the “Carole King chords.” What makes her music pop to you?

Part of why I’m so glad that I did endeavor to take piano lessons is that just learning to play her music made me realize that, while her tunes and lyrics may have this kind of catchy veneer, there’s an emotion that comes from the more complicated chords. I had a lot of trouble learning how to play “Beautiful,” because the chords there are just really hard, but you’re not aware of it when you listen to her. I think she felt that that was a legacy from Richard Rodgers and others who had come before her, and she just experimented with that. I think I also realized that once she became a performer, so many of her songs had the melody that she sang, and then there were chords beneath it, and so the chords were able to give it so much texture.

Tapestry was very meaningful to you. Is that your favorite album? Do you have a favorite song?

I love Tapestry, but I think it’s really important not to forget the albums that immediately succeeded it. Music was released at the end of 1971. It was quite remarkable that she had two big hit records released in the same year. So I really loved Music. I love Rhymes & Reasons. Wrap Around Joy has some great songs in it.

I don’t have one favorite song, but there are songs that I identify with different stages of my life. I mentioned how “Will You Love Me Tomorrow” was so meaningful in high school, and I think I came later in life to appreciate “Natural Woman.” Not that I didn’t think it was amazing. But by learning to play the song and learning music, I realized that it has a real Gospel quality to it that makes it kind of remarkable that two Jewish kids wrote this.

But because of that, I kind of feel like it’s meditative. It seems that the singer is telling this to a lover. But I kind of feel like you could also read it as the singer talking about the divine. And that didn’t strike me until much later in life.