The church preacher who gave sermons in Yiddish

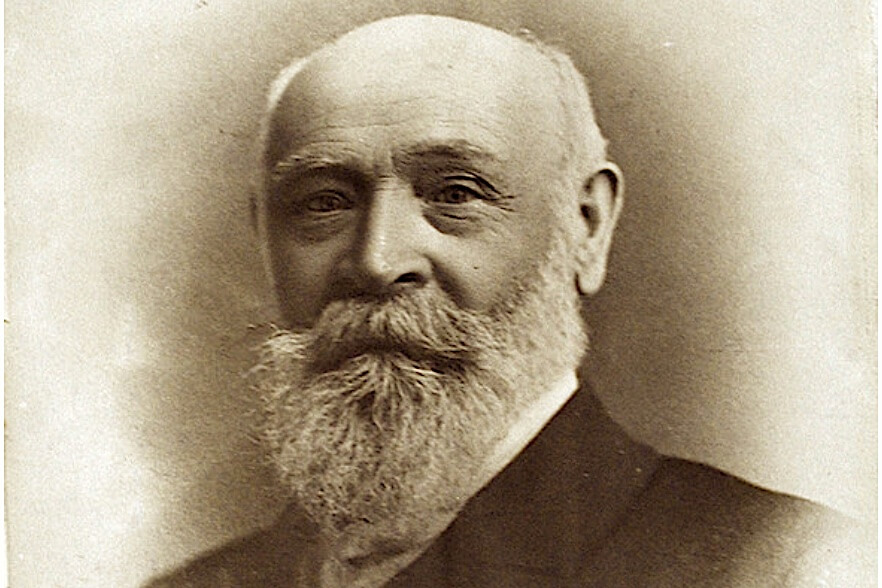

Joseph Rabinowitz, a 19th century Hasid who found Jesus, hoped that his Christian-Jewish sect would improve the fate of the Jews

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

A version of this article appeared in Yiddish here.

The notion of church congregants listening to a sermon in Yiddish may sound like something out of a comedy routine. But in 1882, a Jewish man by the name of Joseph Rabinowitz founded a Christian-Jewish sect in the Jewish community of Kishinev, Bessarabia, where he did indeed preach his original gospel in Yiddish.

Born in 1837 in the Bessarabian town of Resina, Rabinowitz’s pious Hasidic upbringing gave no hint of his future fascination with Christianity. His mother died when he was a young child so he and his father moved into the home of his maternal grandparents, members of the Hasidic court of the Roshkever Rebbe.

Recognizing young Joseph’s keen interest in learning, his grandfather devoted himself to teaching him Torah. At age six, Joseph was able to recite Shir hashirim (“The Song of Songs” by King Solomon) by heart.

“I remember well how in my eighth year I repeated the whole tractate Succoth … and how the Tzaddik warned my grandfather not to let me become too precocious,” Rabinowitz wrote in his autobiography. The Tzaddik, which means the righteous one, referred to his grandfather’s rebbe, Yakov Shimshon of Shepetovke.

By 1848, Joseph’s grandfather had become too sickly to teach him so the child was brought to live under the care of his widowed paternal grandmother, Rebecca. She was called the rabinerin (the woman rabbi), presumably because she could read the Hebrew prayers, unlike other women who were often illiterate.

While they lived under her roof, Joseph’s father paid rabbis to teach his son Talmud. At some point during his teen years Joseph began learning kabbalah and the mystical writings of the Hasidic rebbe Pinchas Koritzer.

Discovering secular literature

In the 1850s, an edict was issued by the czar compelling all Jewish children to learn to speak and read Russian, and all teachers to read Moses Mendelsohn’s German translation of the Bible to their pupils. As a result, Rabinowitz — like many of his peers — got swept up by the new ideas of the Haskalah (the Jewish Enlightenment) promoting secular education and Jewish nationalism, and took to reading secular Hebrew literature.

“A new spirit began to stir in me, and new ideas as to the real meaning of the Law and the Prophets served to infuse doubts in my mind as to the absolute sacro-sanctity of my Hasidic instructors,” Rabinowitz wrote.

Sometime after 1855, a young man named Jechiel Zvi Herschensohn (who would later marry Rabinowitz’s sister) gave him a Hebrew translation of the New Testament, called the bris khadoshe in Yiddish, suggesting that perhaps Jesus was the Messiah. Knowing that Herschensohn was well-versed in the Talmud, Rabinowitz read it and hinted in his autobiography that this was a turning point in his thinking.

In 1856, Rabinowitz married a girl from the Bessarabian shtetl of Orgeyev named Golda Goldenburg and moved into his father-in-law’s house as was the custom among Jewish newlyweds. Using part of his wife’s nadn (dowry), he opened a small shop but a year later the store burned down in a huge fire that destroyed most of the town.

Urging Jews to become farmers

Several years later he started a business in tea and sugar and in 1871 he moved to Kishinev. At the same time he was becoming increasingly concerned about the poverty and antisemitism Jews were facing daily. “I heard an inner voice saying to me: ‘Leave trade and traffic; it will bring thee no blessing. Be an advisor and an advocate of thy oppressed people, and I will be with thee!’ I obeyed what I felt was a divine call.”

He began working as a Jewish community leader and writing for secular Hebrew newspapers. In 1878, he penned an article, urging his fellow rabbis to sponsor agricultural training for the Jews in order to improve their lot. Together with his sons David and Nathan, Rabinowitz even cultivated his own garden, hoping to serve as “a practical example” for the Jewish people.

After the bloody pogroms in the Russian Empire in the 1880s, Rabinowitz became disillusioned with a future for Jews in Europe altogether and traveled to Palestine, hoping to start a farming collective there. But the dismal conditions in Jerusalem at that time convinced him that his plan was futile and he returned to Kishinev.

In 1888, George Schodde, a missionary, wrote that while Rabinowitz was in Jerusalem, he began to see Christianity as “the solution” to the Jewish problem. “While smarting under his repeated disappointment and perceiving that Palestine had offered no hope, he finally came to the conclusion that what Israel needed was not material improvements but a moral regeneration, and that this moral regeneration must be the work of that spirit of Jesus,” Schodde wrote.

A synthesis of Judaism and Christianity

Whether Rabinowitz actually had this revelation in Jerusalem or not, he did return to Kishinev with the idea of creating a kind of synthesis of Judaism and Christianity which he believed could help the Jews integrate better into society. Under the influence of a missionary named Faltin, Rabinowitz founded a sect called Israelites of the New Testament.

On Christmas Day, 1884, he opened a prayer house called Bethlehem, where he told his new congregants that they could continue to keep their Jewish names, observe the Sabbath and circumcise their newborn boys, even if the liturgy itself was Christian. His wife, Golde, his brother-in-law and other relatives were among the first to join. Because Yiddish and Hebrew were familiar to the Jews of Kishinev, Rabinowitz frequently delivered his sermons in Yiddish and led the prayers in Hebrew.

“He used Yiddish because he wanted to reach the poor Jews of Kishinev,” said Steven J. Zipperstein, professor in Jewish culture and history at Stanford University. “All of them knew Yiddish.”

Bethlehem’s Sabbath services immediately attracted large crowds, mostly curiosity-seekers, Jews eager to witness the remarkable sight of a Jew preaching about Jesus in Yiddish, Zipperstein said.

The incongruity of using Yiddish and Hebrew in a church wasn’t lost on C. M. Mead, a Christian missionary, who attended the services. “I take delight in the favor of God upon the distribution of sermons in the language of Russia, in Hebrew, in German and in the Jargon.” Historically, the Yiddish language was often referred to as Jargon (pronounced zhar-GON) — a pejorative term meaning a hodgepodge of languages.

Another missionary called Rabinowitz “a preacher of the gospel in the spirit of Jewish nationality” whose sermons were published in Hebrew, Russian, “and in the jargon called Yiddish, which reached ten thousand copies.”

He refused to give up his Jewish name

The Jewish community of Kishinev was outraged at the establishment of this supposed “church-synagogue” and told czarist government officials about it. Eventually, the government ordered the church shut down. “The Russian authorities were nervous about the rapid rise of Protestant Christianity,” explained Iemima Ploscariu, an expert on 19th century messianic Jewish leaders. “They saw it as heretical to Russian Orthodoxy.”

This didn’t diminish Rabinowitz’s fervor, though, and sources indicate that he continued holding services privately in his home. In 1885 he converted to Protestantism and published his own prayer book in Hebrew and English.

Interestingly, Rabinowitz never let go of his Jewish identity. Although most Jewish converts to Christianity were expected to adopt a Christian name, Rabinowitz refused to do so. He died of malaria in May 1899.

So what do we make of this complex man? It’s clear that at least part of Rabinowitz’s motivation in creating a culturally Jewish church was his desperate desire to usher in a more promising future for the Jews. While other Jews fought for political equality, he believed that by creating a sect uniting Judaism and Christianity, the Jews would be warmly welcomed by their non-Jewish neighbors.

But he insisted on doing it his way. Right before getting baptized in Berlin in 1885, Rabinowitz told the Christian authorities who were supervising the conversion that he still wanted to be able to tell his followers that they could continue to keep the Sabbath and practice circumcision. Reluctantly, they agreed.

“It was clear that he didn’t want to separate himself from the Jewish community,” Ploscariu said. “He loved his Jewish heritage and wanted to see it valued as it should be — both by converted Jews and Christians.”