Both the Right and Left Get the Muslim Ban Wrong

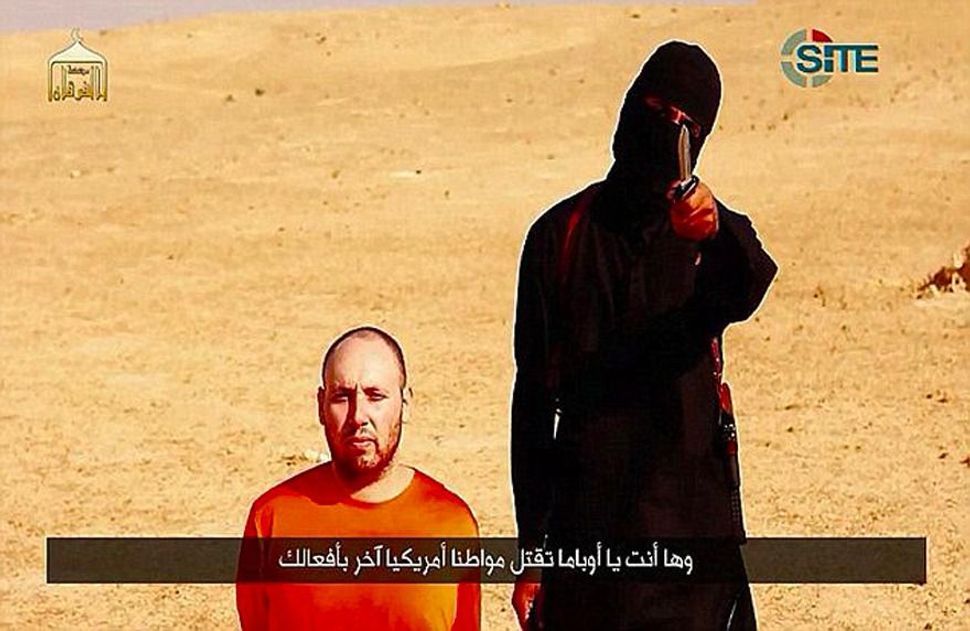

Image by ISIS Video

Donald Trump’s executive order temporarily barring nationals of seven predominantly Muslim countries from entry to the United States has sparked a new round of furious — and fruitless — debate about Islam, terrorism, and Islamophobia. One side all but dismisses militant Islamism as a phantom menace, touting statistics to show that lawnmowers and armed toddlers are a more potent threat than jihadist terror. The other equates Islam itself with terrorism and regards every Muslim toddler as a potential jihadist. Meanwhile, very real issues are getting lost amidst the polemical histrionics.

Trump’s “Muslim ban” is a good example of how not to deal with these issues. True, as the White House has pointed out, the order covers only countries designated as terror risks under the Obama administration, while leaving the vast majority of the world’s Muslims unaffected. But given that during his campaign, Trump explicitly called for a “total and complete shutdown of Muslims entering the United States” for an indefinite period of time, it’s hardly surprising that his order is being called a “Muslim ban.” Indeed, former New York mayor Rudy Giuliani has said that Trump was looking for a legal way to enact such a ban.

Speaking at a timely conference on immigration in Washington, DC on Monday, George Mason University law professor Ilya Somin noted that a policy with discriminatory intent is still illegal even if its wording is technically neutral—and that, while presidential authority in the area of immigration may make such an order exempt from anti-discrimination law, it is no less morally offensive. (Disclosure:Reason magazine, where I am a contributing editor, sponsored the conference).

The perception of religious animus is strengthened by the fact that some of Trump’s top aides, including National Security Advisor Michael Flynn, have made sweeping statements against Islam. While at times Flynn has limited his criticism to radical Islam, in a speech in Dallas last August he asserted that Islam is not a religion at all but “a political ideology [that] will mask itself as a religion” and a “malignant cancer.”

Lt. Gen. Michael Flynn at the U.S. Capitol during President Donald Trump’s inauguration ceremony, Jan. 20, 2017. Image by Getty Images

Such sentiment has been brewing on the right for some time; it first gained mainstream visibility during the 2010 backlash against the so-called “Ground Zero mosque” proposed in lower Manhattan by the Cordoba Initiative. The attacks on the faith readily translate into hate toward its followers. “Counter-jihadist” websites Jihad Watch and Atlas Shrugs relentlessly hype the “Muslim peril;” halal food at Walmart becomes “creeping sharia” and even car accidents involving drivers with Muslim-sounding names are promoted as “vehicular jihad.”

Some haters also suggest that moderate or even secularized Muslims in our midst are still dangerous, since they or their children could always relapse into militancy. Many Trump fans in the social media argue that all practicing Muslims should be prohibited entry to the United States under a 1952 law barring subversive aliens.

This blanket bigotry should disturb all Americans as a thinly veiled attack on the First Amendment, especially when Flynn and other polemicists openly suggest that Islamic ideology “hides behind” religious freedom. It should be especially disturbing to Jews, who have long been on the receiving end of similar prejudice; the widespread assertion that Islamic doctrine encourages lying to non-Muslims (a vastly oversimplified, distorted rendering of Shia Islam’s concept of Taqiya) mirrors anti-Semitic claims that the Talmud encourages Jews to cheat gentiles. Today, the so-called “alt-right” frequently combines anti-Muslim bigotry with anti-Semitism, accusing Jews of promoting Muslim migration to subvert Christian societies.

Unfortunately, the liberal response to this far-right ugliness often sidesteps real problems within Muslim culture — including anti-Semitism.

While not all terrorism is Islamist, no other ideology has a comparable global terror network. In a last June, Julia Ioffe rightly argued that “no religion is inherently peaceful or violent.” But while Christianity, Judaism, and Hinduism have their extremists, they have no modern counterparts to terrorist groups such as Al Qaeda or ISIS — whose beliefs, as mainstream journalist Graeme Wood has argued in The Atlantic, is rooted in Koranic texts (even if it is far from the only interpretation).

Only a small minority of Muslims worldwide sympathize with ISIS, and numerous Muslim clerics and organizations condemn it. But Islam also has a larger extremism problem — again, currently unmatched by other major religions. A 2013 Pew Research Center poll found that majorities of Muslims in many countries, including Afghanistan, Egypt, and Pakistan, favor the death penalty for adultery and apostasy; in Pakistan, the assassin of a liberal politician who had advocated changing draconian blasphemy laws became a hero to many. Intolerance toward religious minorities, particularly Jews, is also rampant.

Of course, sweeping generalizations serve no one. Islam is no monolith, even in its approach to such issues as blasphemy; it has always incorporated a multitude of sects, theological schools, and cultures. The 2013 poll found little support for sharia law, and even less for harsh religion-based punishments, among Lebanese, Central Asian, Turkish, or Bosnian Muslims. Yet unfortunately, radical Islamic fundamentalism and political Islamism have been expanding their reach across the Muslim world due to many factors, including Saudi financing.

Radicalism is also a real problem in Muslim communities in Europe, even if its dangers get overhyped in the right-wing press. French television has on suburbs in which women are unwelcome in public spaces. The global advocacy Jewish advocacy group AJC, which criticizes hateful rhetoric against Muslim migrants, has also cautioned that more must be done to counter the anti-Jewish hate many may bring from their cultures.

While American Muslims as a group are much more integrated and moderate than in most of Europe, they are not immune to the global influence of Islamism. Interestingly, extremism may be especially common — a problem restrictions on Muslim immigration will not address and may even exacerbate. The perception that America is waging war on Islam can make Islamist radicalism more of a magnet for the disaffected.

The real promise lies in the movement for Islamic modernization and reformation, embraced by leaders like British Pakistani Muslim Maajid Nawaz and American physician and activist Zuhdi Jasser. Yet these reformers have been attacked both by anti-Muslim bigots and by supposed progressives who equate their criticism of authoritarian, reactionary Islamism with Islamophobia.

On the campaign trail, Trump repeatedly blasted Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton for not naming the problem of radical Islamism. Some reformist Muslims such as Washington, DC-based journalist Asra Nomani — who voted for Trump — concur. Yet if the Trump White House is seen as pursuing anti-Muslim policies, it can make leftists, liberals, and even centrists more reluctant to speak against extremism in Islam.

Secularist author Sam Harris warns that liberals who refuse to confront Islamism and support reformers can only “empower Trump” — while Trump’s ill-considered actions such as last week’s travel ban can only empower Islamists. We must do what we can to resist this vicious cycle.

Cathy Young is a contributing editor at Reason magazine. Follow her on Twitter @CathyYoung63