Joan Nathan’s new cookbook is about much more than food

’My Life in Recipes’ is the Jewish text we need right now

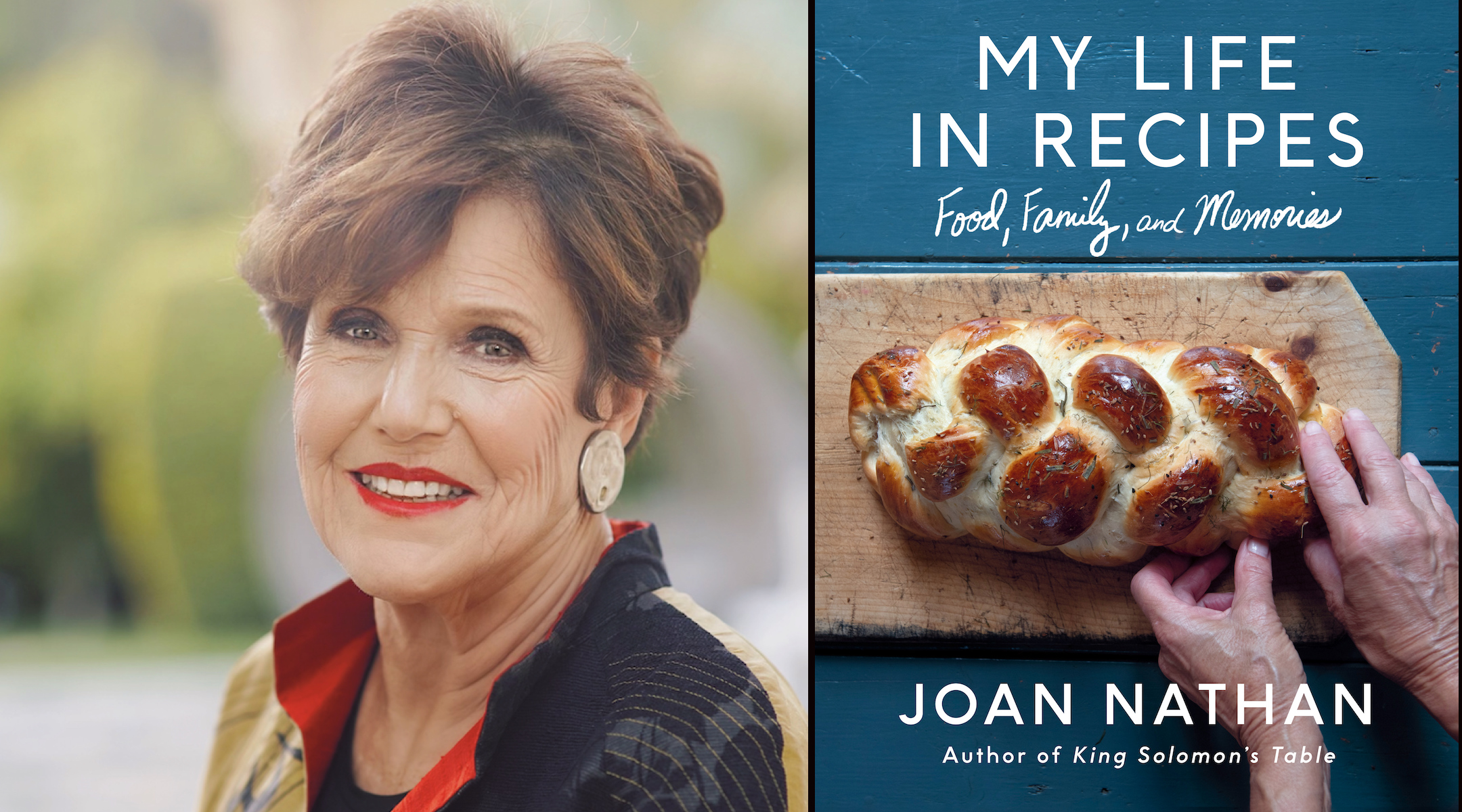

Joan Nathan’s 12th cookbook, My Life in Recipes, takes readers through her family story. Photo by Hope Leigh/Knopf

In January 2023, dozens of Joan Nathan’s family and friends gathered at a sprawling Palm Springs home to cook for the celebrated cookbook author and food journalist on her 80th birthday. A dozen of us worked around a center island stacked with produce, preparing dishes for the menu’s theme, foods of the Jewish diaspora. I made chicken-stuffed figs with onions and tamarind, a recipe I took from the Jerusalem chef Moshe Basson, whom Joan had long ago told me to look up on a visit to the city.

Nearby, the Chez Panisse alum and author David Tanis chopped fennel. Glenn Roberts, the founder of Anson Mills, the celebrated heirloom grain company, strapped on an apron and washed dishes. Shelly Yard, the former Spago pastry chef, walked in with a multi-tiered cake. Tara Lazar, the host, rolled through phone calls to the area restaurants she owns while also, somehow, directing the ebb and flow of event staff.

At that point I’d known Joan Nathan for over 20 years, when a 2001 assignment to interview her for her book, The Foods of Israel Today, evolved into a treasured friendship. So it wasn’t surprising to me that a woman best known for collecting recipes genuinely excelled at collecting friends.

Her newest book, My Life in Recipes: Food, Family and Memories, is certainly about food — it features 100 wide-ranging recipes. But more importantly it points, poignantly and repeatedly, to what all that food is for: bringing joy, meaning and strength to family and friends.

“Who needs champagne?” Lazar shouted.

Just then, Joan came in and looked around at the controlled chaos.

“This,” she said, “is just what I wanted.”

At a time when Jewish life seems tenuous and in turmoil, Joan’s memoir is a reminder that there is something permanent, powerful and affirming in our tradition and culture. No matter how dark the news may be, Jews for centuries have found respite in coming together and cooking the foods of our diverse communities, grounding us during uncertain times. Who’d have guessed that a cooking memoir is the Torah we need right now?

A lark turned into a profession

We all have Jewish food memories. Joan just happens to remember, and research, and write, hers better. The memoir’s glossy pages tell the story of her constant interest in food growing up as a child in New York through vibrant color photos and astute recipes: her immigrant father’s German family’s sweet and sour carp, her assimilated mother’s whitefish salad, the pletzlach of the Parisian Jewish quarters, mango poached in vanilla syrup from a sojourn in Madagascar.

“I realize that I learned to love exploring the world of New York’s foods from my mother’s side of the family,” Joan writes, “while from my father’s I learned the importance of knowing one’s own roots and the family recipes that kept memories alive.”

The exploration continued through college and, eventually, to Jerusalem, where in 1971 Joan scored a job working as the foreign press attaché for the city’s charismatic mayor, Teddy Kollek.

Jerusalem was a graduate course in Jewish foodways, and as Joan explored the city, she gathered the stories and recipes.

Eventually Joan hit on the idea of a cookbook that would enable visitors to get to know Jerusalem’s people through their recipes.

“We did this as a lark,” she writes, “and it turned into a profession for me.”

An ambassador for Jewish food

The Flavor of Jerusalem, coauthored with Judy Goldman, came out in 1975, and it was a hit. Joan’s profession, which led to classic works like Jewish Holiday Cooking, Jewish Cooking in America and King Solomon’s Table, not only helped generations of Jews set the table, but expanded their understanding of Jewish peoplehood and history. Consider garosa, the charoset of the Jews of Curaçao: a mash of dried fruit, nuts, spices and sweet wine rolled into balls to symbolize the flight of Sephardic Jews from the Spanish Inquisition.

Though not mentioned in the Torah, charoset explains, “more than any other food the wandering of the Jewish people in a Diaspora that extends around the world,” Joan writes.

The memoir gives you an idea of the energy, focus and precision that Joan, a regular contributor to The New York Times‘ food section, brings to researching and writing recipes and the stories behind them.

I saw it firsthand, many times. One day last summer, Joan and I walked into a Russian bakery in LA’s historically Jewish Fairfax district, our first stop of the afternoon on what I feared would be a fruitless search for the exact spinach-stuffed Armenian pastry that Joan remembered from a dinner party.

“That’s it!” Joan lit up, pointing inside the display case.

Except that wasn’t it — it was instead a layered honey cake that Joan had also long been researching.

She immediately asked the counter woman where she was from — Uzbekistan — and if she could come back and watch the baker make the cake.

“No,” the woman said.

“I’m a food journalist,” Joan said, explaining that most Jews think of honey cake as dry and unexciting, but this looked more like the Hungarian version, which has a soft, gingerbread cookie-like crumb and creamy layers.

The woman’s resistance fell away. “He’s not here right now,” she said, “but you can come back.”

A few weeks later, I clicked on The New York Times‘ website and there was Joan’s story on Hungarian honey cake.

Recipes complicated by war

But some of those stories, just in the short span since Joan finished the memoir last year, have become infinitely more fraught.

The optimistic post-1967 Israel that Joan first fell in love with has been shaken by the Oct. 7 Hamas attack and tarnished by Israel’s relentless response in Gaza.

“It breaks my heart,” she said when I reached her by phone. “What else can I say? It’s awful what’s happened for Israelis, for the Palestinians.”

In 2018, Joan served as a consultant on a U.S. State Department project to help Syrian, Afghan, Turkish and Palestinian women start food businesses in Istanbul. She cooked alongside them, she writes, “sharing our mutual humanity and building trust.”

Given the current climate, when even hummus is a social media battle cry, it’s hard to imagine such an event happening again any time soon.

Late in the book, the chef José Andrés appears. An old family friend, Andrés shows up with a brown crock filled with a rich chicken soup when Joan’s husband Allan Gerson, a renowned international lawyer, is dying of a rare disease. Later, during Allen’s shiva, Andrés returns to Joan’s Washington, D.C., home, this time to make a comforting oxtail soup.

“I shall never forget how this larger-than-life, big-hearted man who rushes to feed millions of people in crisis the world over helped me, just an everyday friend,” Joan writes.

Israel’s killing of seven aid workers from Andrés’ charity World Central Kitchen, on April 1, brought yet more heartbreak and shock. The two have been in constant touch. “It destroyed him,” she said. “My heart broke for them and him.”

The sadness of what’s happening in Israel and the Jewish world today makes My Life in Recipes more relevant, not less. Strength and survival, Joan’s book makes clear, is with tradition, food and friends.

Her husband’s sudden death, at age 74, frames the book. The two shared a life of great food and adventure, and when Joan suddenly found herself bereft, it was her three children, extended family and friends who filled her kitchen with food. Her community, she writes, “helped me slowly get out of myself and into the power of living.”

My Life in Recipes turns out to be not really, or not just, about recipes. It’s about how a life with food helped Joan face sorrow, how the deep friendships she forged in the food world revived her spirit, and how the rituals and recipes of her tradition returned her to life.

They may just help us all return.