Is Haredi Music Video Activism Misplaced?

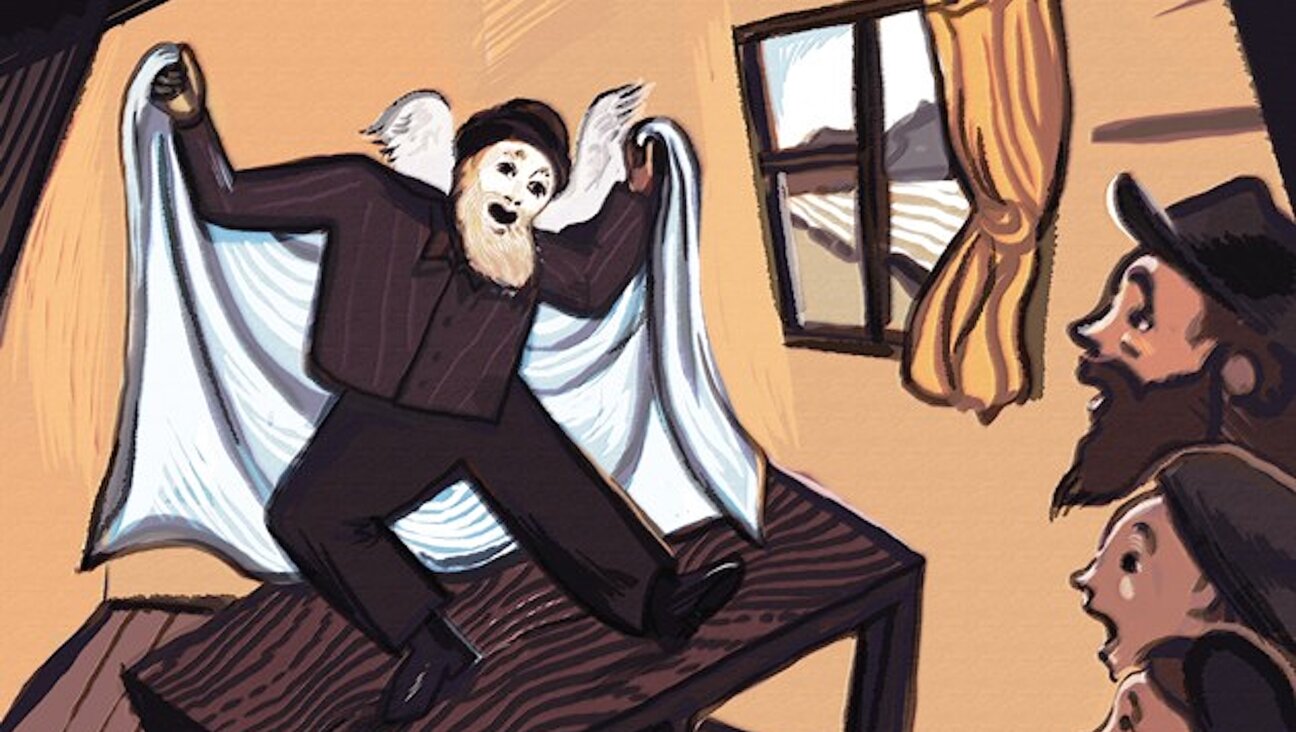

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

The new single and music video titled “The Japan Song,” released March 29 and featuring prominent Hasidic singers Avraham Fried and Shloimy Daskal, is not what you might expect. Although its purpose is fundraising for relief efforts, and the video includes some footage of the tsunami, it is not a fundraiser for Japan at all. Rather, it is the latest in a new trend of Haredi musical activism on behalf of Jewish prisoners.

In the spring of 2008, Yoel Zev Goldstein (then 22), Yaakov Yosef Greenwald (then 19), and Yosef Banda (then 17), three young Hasidim from Bnei Brak, Israel, were arrested at Japan’s Narita International Airport after customs officials found $3.6 million worth of Ecstasy pills hidden inside their suitcases.

According to the young men, they believed they were delivering legal antiques from Amsterdam to Tokyo for an acquaintance, and were unaware that the suitcases had drugs inside them. In February 2009, Israeli police arrested two Hasidic men for allegedly scamming the trio into smuggling the drugs.

Banda, the youngest of the group, was tried and sentenced to five years in prison. Pursuant to a prisoner transfer agreement he was transferred to Israel in March 2010, where the President of Israel, Shimon Peres, commuted his sentence, and he was released on December 30, 2010. Meanwhile, Greenwald was tried and sentenced to six years in Japan (though an appeal is currently underway), and Goldstein’s trial is ongoing.

The video features a new interpretation of a classic song, “In A Vinkele,” by the group D’veykus, which was recently re-popularized with different lyrics by Yaakov Shwekey. “The Japan Song” version features purpose-written lyrics in both Yiddish and English: “Did you ever see an angel cry / for a misplaced soul / and you kept on walking by no time / ’cause you had to go / now pretend the soul is you / thousands of miles away ’cause you made a mistake.”

“The Japan Song” release was unfortunately ill-timed. The website URL, song title, and video had all been announced prior to the tsunami, but the final video was not completed until after the tragedy. In an effort to forestall how the tsunami footage was likely to be viewed by many (as divine retribution, perhaps, for prosecuting the Hasidic smugglers), the producers added the following clarification to the website: “The Tzunami [sic] footage in the clip was implemented [sic] as a sign of solidarity with the tragedy that struck the great Japanese nation.”

This is the second recent music video in support of frum lawbreakers. The first one, “Unity for Justice,” was released in October 2010 on behalf of Sholom Rubashkin, who is serving a 27-year sentence on financial fraud charges relating to his management of the Iowa-based kosher meat factory, Agriprocessors.

“Unity for Justice,” a remake of the Mordechai Ben David song “Unity,” featured a veritable who’s who of contemporary Hasidic singers, two religious hip-hop artists (Y-Love and DeScribe), and rock guitarist C Lanzbom of Soulfarm in a “We Are The World” style anthem for Rubashkin. The lyrics included lines like, “Eagle soaring by / Could you lift him up with you now / And fly him home with justice, pride and freedom / His eyes are gazing wide / From behind the bars he prays now / With faith, with joy, oh how we wait to greet him.”

In each of these cases, in addition to the music videos, there have also been community gatherings to raise awareness and solicit funds. At these events, the focus is on the prisoners and their suffering — described in hagiographic language — instead of on the cautionary lessons the community might absorb. Attention is concentrated exclusively on the personal experiences of the individuals in question, without reference to the broader issues involved, like federal sentencing guidelines. The “Unity for Justice” website ignores the subject, though those who feel that Rubashkin’s sentence is inappropriately long would do well to address it.

In the Japan case, the evidence indicates that although the trio were carrying Ecstasy, it was most likely as “blind mules.” There too, activists focus solely on the men in jail, and ignore the question of whether strict sentencing should apply equally in cases where the perpetrators were unwitting, as well as the social conditions that made these young men vulnerable to becoming drug mules, wittingly or not.

One would think that addressing all of the underlying issues — rather than merely defending the prisoners — would be beneficial to the imprisoned, and might help prevent others from finding themselves in similar situations.