‘Faust’ author Goethe’s fascination with Yiddish

As a boy, Goethe visited Jewish schools in Frankfurt, and even attended a circumcision and a Jewish wedding

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe as a young man in a painting by Angelica Kauffmann, 1787. Image by Angelica Kauffmann via Wikimedia Commons

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe is usually remembered as a towering figure of European culture: poet, playwright, scientist, and all-around genius of the Enlightenment.

His drama Faust opens with a scene that echoes the Book of Job, where God makes a wager with the devil over whether a good man can be led astray. What far fewer people know is that Goethe’s connection to the Bible was not just literary. He actually learned Hebrew so he could read it in the original — and his path to Hebrew ran straight through Yiddish.

Goethe was born in 1749 in Frankfurt am Main into a well-to-do Christian family. Frankfurt was also home to a densely packed Jewish quarter, the Judengasse (German for “the Jewish street”). As a boy, he ventured there, feeling both nervous and curious. In his autobiography, Poetry and Truth, published in 1833, he recalled what it was like for a German boy to step into a crowded world of people who dressed differently and spoke a strange-sounding German he called Judendeutsch (Jewish German).

But instead of fear or disdain, what stayed with him was fascination. He remembered friendly people and beautiful girls, and he was struck by the sense that the Jews carried ancient history with them into everyday life. They were, he wrote, “the chosen people of God … walking around in memory of the earliest times.” Even their stubborn attachment to tradition, he felt, deserved respect.

Goethe wanted to see more. He described how he insisted on visiting Jewish schools, attending a circumcision and a wedding, and getting a glimpse of Sukkot. Everywhere, he recalled, he was welcomed, entertained, and invited back. For an 18th-century German boy, this kind of contact with Jewish life was unusual — and it clearly made a lasting impression.

At home, Goethe was buried in languages. His father hired tutors to teach him Latin, Greek, English, French and Italian. Goethe learned quickly but soon grew bored with endless grammar drills. So he did what any restless young writer might do; he turned language learning into a game.

He invented a novel made up of letters exchanged by seven siblings scattered across Europe. Each sibling wrote in a different language: A music historian in Rome wrote in Italian, a Hamburg businessman in English, while a theology student wrote Latin and Greek. The youngest sibling stayed home and wrote in Yiddish. The effect, Goethe later suggested, was both amusing and confusing for the other characters.

That detail is telling. Goethe treated Yiddish as something playful and odd, a kind of Jewish-flavored German. But he knew it well enough to use it creatively.

In his autobiography, he describes the seven-language novel but doesn’t give it a title. We can guess, though, that his Yiddish was the Western Yiddish spoken by Frankfurt Jews at that time. A sentence like ikh vil kaafen flaash (“I want to buy meat”) would have sounded close to the local German dialect, but not quite the same.

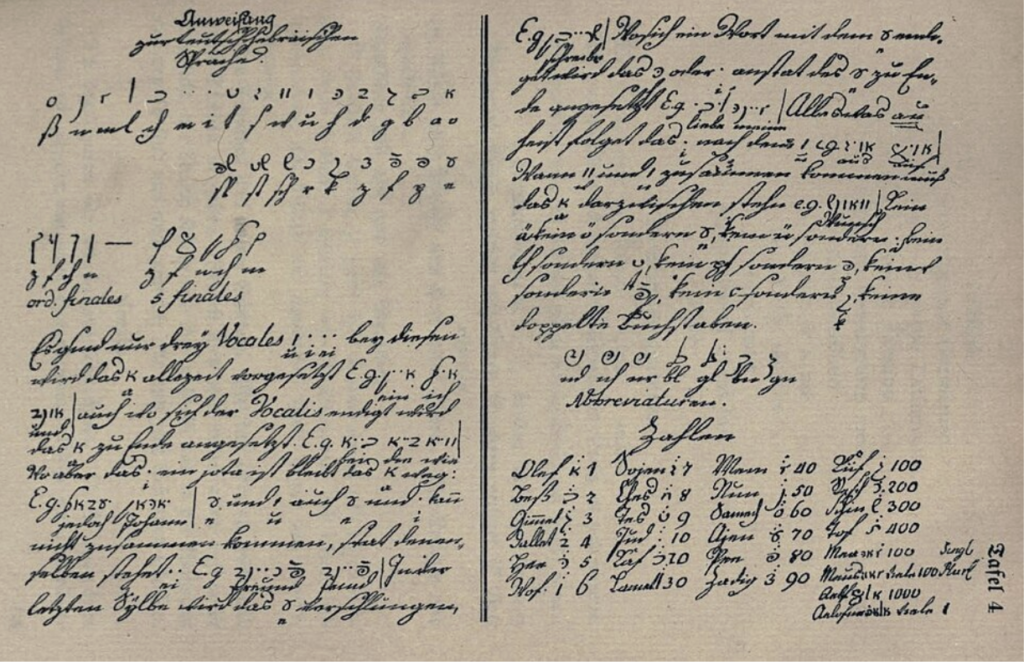

Goethe soon realized that if he wanted to understand Yiddish properly, he would have to learn Hebrew. His father arranged a tutor, and young Goethe plunged into a whole new alphabet. Although the location of his childhood notebooks are unknown, two of its pages are located online. On them, he carefully writes out the Hebrew letters, their names, sounds and even their numerical values. His notebook contains reminders to himself that Hebrew words are built from three-letter roots and urges himself to practice again and again so the forms would stick in his memory.

It wasn’t easy. Goethe later wrote that he got used to reading from right to left and identifying the letters, but was confused by all the dots and dashes — the vowel points, that seemed to complicate things even further. Still, he pushed on. He learned to read the Hebrew Bible and even tried his hand at writing a German epic based on stories from Genesis.

His interest in Yiddish didn’t disappear with childhood. When he was 17, Goethe apparently wrote a Purim play in Judendeutsch, written in Hebrew letters, complete with a translation into High German. Years later, he translated the Song of Songs into German. The Bible became a lifelong companion — not just as literature, but as a moral guide. “I loved and valued the Bible,” he wrote, “and owed my moral education almost entirely to it.”

As Goethe grew older, his ideas expanded in many directions. Influenced by the Jewish philosopher Baruch Spinoza, as well as Persian, Sufi and Buddhist writings, he developed a broad, inclusive worldview. He dreamed of something he called Weltliteratur — world literature — a shared cultural space where the works of all peoples could speak to one another.

Near the end of his life, Goethe said that the age of world literature had arrived, and that everyone should help bring it about. Seen this way, his childhood journey — from the Judengasse, through Yiddish, to Hebrew — was more than a youthful curiosity. It was an early step toward a vision in which cultures, languages and traditions are not sealed off from one another, but connected.

For Forward readers, there is something especially satisfying in this story. Yiddish appears here not as a joke or a dead-end dialect, but as a bridge — linking everyday Jewish life to the Bible, and even carrying one of Europe’s greatest writers toward a deeper engagement with Jewish tradition and, ultimately, with the idea of world culture itself.