The Jewish Museum’s new exhibit is barely Jewish. Does that matter?

A new exhibit on the early ’60s has little to do with Judaism or Jewish identity. Why is it at the Jewish Museum?

“Self-Portrait” by Marisol. Photo by Mira Fox

The ’60s was a famously explosive decade in every sphere — art, history, politics and even consumer culture. There was the intensification of the civil rights movement and the assassination of President John F. Kennedy. The invention of color TV and the emergence of Pop Art.

And the Jewish Museum, which had recently moved into a small mansion on Manhattan’s Museum Row, became “one of the most important cultural hubs during this time.” Or so claims a new exhibit at the Jewish Museum, “New York: 1962-1964.”

The museum’s newfound influence was due in large part to its curator during those three short years: Alan Solomon. Solomon hoped to establish what he called the “New York School” as an international center of artistic innovation, and used his position at the museum to highlight what he called “New Art” and artists who would become influential heavyweights, such as Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns.

Solomon’s impact, including representing the U.S. at the 1964 Venice Biennale, helped establish New York City as a center in the worldwide art scene. Over two floors in the museum, his influential taste for the avant-garde and experimental is clear. There’s sculpture made out of found items and paintings both abstract and realist, yellowed poetry journals and black-and-white clips of George Balanchine’s ballets flickering in projections against the wall. In one room, a ’60s-style kitchen is set up complete with orange patterned wallpaper and an old radio, and in another, an Eames chair sits next to a cathode-ray TV set playing old advertisements. Newsreels show Walter Cronkite describing first lady Jackie Kennedy’s blood-spattered dress after her husband’s shooting, and the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. delivering his “I Have A Dream” speech.

But many of the artists included in the expansive exhibition, including Rauschenberg and Johns, aren’t Jewish — a fact that naturally raises questions. How did the Jewish Museum’s mandate situate it in the New York art scene in the early ‘60s? And how does it fit in now?

Two Forward critics went to the exhibit and chatted about it over slightly stale croissants at a nearby bakery that shall not be named. Here are some snippets from our conversation.

Couldn’t any museum have staged this exhibit? What’s even Jewish about it?

IRENE: I’ve been to a lot of exhibits at the Jewish Museum, and I find my favorites are the ones in which the Jewish angle isn’t quite clear. The reality of life for diaspora Jews, especially those living in a crowded, diverse place like New York, is that even if you wanted to, it’s just not possible to live in a silo of exclusively Jewish culture and ideas.

For me, exhibits like this present a kind of Platonic vision of how to approach a given moment in history as a curious and open-minded Jew: You’re sensitive to Jewish resonances and themes, but not exclusively focused on Jewish artists or Jewish-led movements.

The exhibit strategy also felt well-suited to the historical moment in question, the postwar years during which Jews were assimilating into white American society at a rapid clip. Professional and educational barriers were eroding, overtly antisemitic discrimination was less common and Jews who once clustered together in urban enclaves were spreading out into the suburbs. It was a time of increased opportunity — today, we see this moment cited all the time as proof that the “American Dream” is or once was a practical reality — and new questions about what it meant to identify as a Jew.

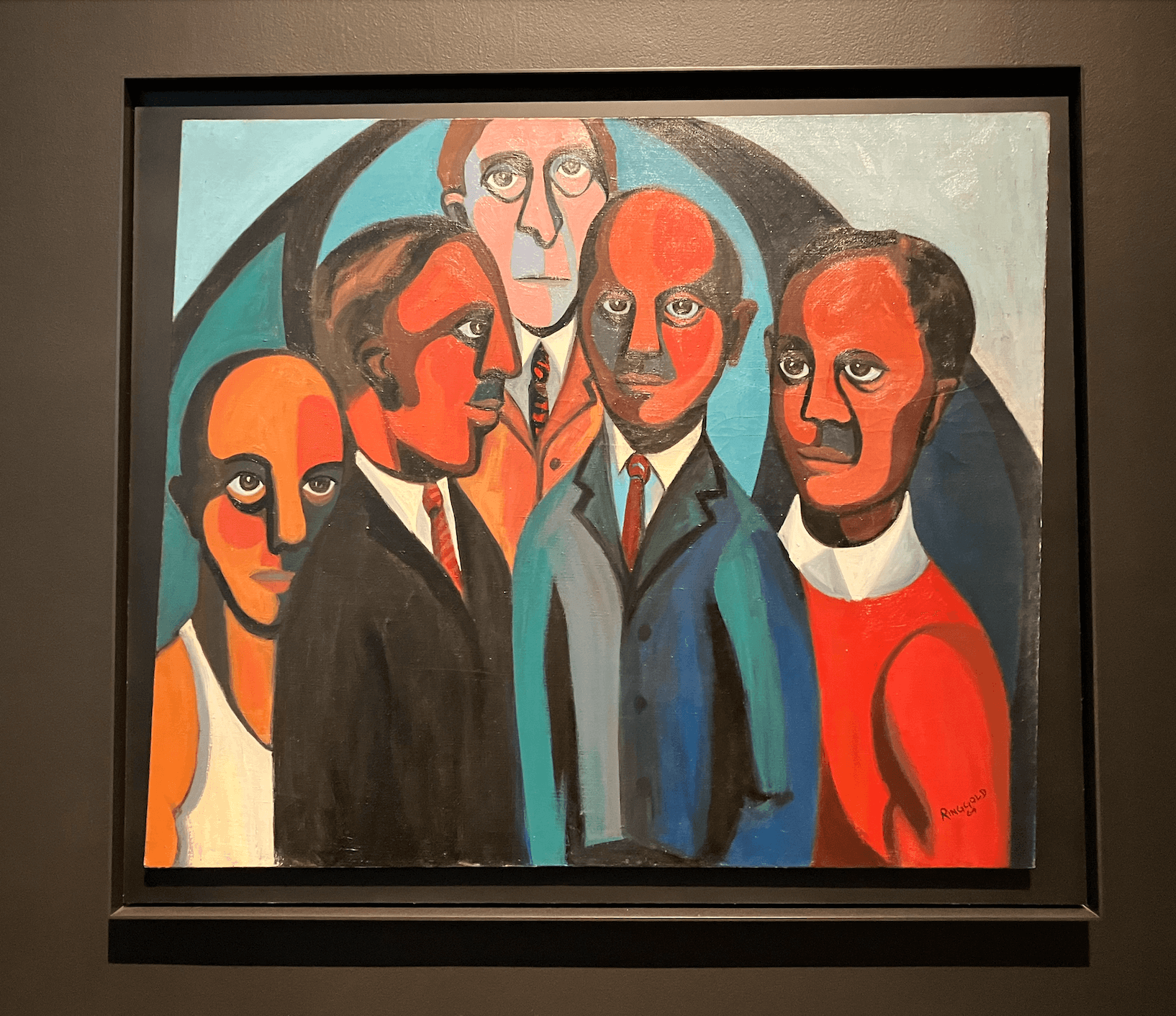

Would the experience of oppression in America spur Jews to join the civil rights movement, or were they going to cling to their tenuous status as white citizens in a segregated society? I thought about this while looking at a Faith Ringgold painting on display. Titled “The Civil Rights Triangle,” it shows a group of Black and white people arranged in a pyramid, with a white man on top; the implication is that the civil rights movement depended on white activists for legitimacy, replicating the inequalities it sought to abolish. Ringgold is not Jewish, and the painting doesn’t reference Judaism in any way, but it would be difficult to contemplate Jewish engagement with the civil rights movement without looking at art like this.

MIRA: The entire time I was walking through the exhibit, I wondered why exactly it was at the Jewish Museum. Is it just because New York is intertwined with the construction of American Jewish identity? Is it because Jews were involved with the social movements of the era?

I don’t mind that the exhibit was not obviously Jewish. I hate the idea of limiting Jewish art to topics that smack you in the face with their Jewishness, like the Holocaust — Jewishness is a multifaceted identity that’s not defined by any one thing.

But I do think part of being the Jewish Museum is needing to at least grapple with the idea of having a Jewish mandate of some kind, even if the result is to reject it. There was space for the exhibit to explore the museum’s mandate as a Jewish art institution and be a really interestingly meta exhibit. It just didn’t take the opportunity.

A lot of the exhibit followed former curator Alan Solomon, who led the museum to play a large role in the art scene of this era, but it didn’t really acknowledge the fact that he was elevating largely non-Jewish artists, like Johns and Rauschenberg, while at the Jewish Museum. Doesn’t it feel like a contradiction that the Jewish Museum became a cultural hub thanks to exhibits of non-Jewish artists? I wish the exhibit had gone into a little bit more depth about Solomon specifically in his role as the head of the Jewish Museum instead of just generally showing that he was a canny curator.

Didn’t way too much stuff happen between 1962 and 1964 for one exhibit to cover?

IRENE: You could devote multiple museums worth of space to art in this time period, and this exhibit tried to condense it all into a couple of rooms. The result was a lot of big ideas without much connective tissue. Urban renewal! Consumerism! The civil rights movement! Costumes! JFK! Ballet! The Venice Biennale! The faux living room and kitchen, well-imagined as they were, really put me over the top with information overload. I definitely started to tap out a bit.

MIRA: It seemed like the exhibit expected everyone coming through to already know what Pop or New Realism are, or who each artist was; there wasn’t enough of any one thing to get a sense organically. I was reading up on some of the artists afterward and realized that many of them were connected — Johns and Rauschenberg were lovers! Donald Judd and Yayoi Kusama shared a studio!

I would have loved to understand during the exhibit that many of the artists were not merely in the same artistic milieu but were actually living and working in community with each other. And not to harp on my point about the Jewish Museum grappling with its Jewishness, but I think that would have given the exhibit a throughline that could have helped make it feel cohesive.

OK, but wasn’t there also a lot of stuff we liked?

IRENE: I was so moved by a Louise Nevelson sculpture on display called “Sky Cathedral’s Presence I.” It’s a hulking arrangement of crates, furniture fragments and other scraps of wood, all painted black, which Nevelson scavenged from the streets around her apartments in Kips Bay. At the time, Nevelson was actually facing eviction. City authorities, led by Robert Moses, were demolishing tons of buildings in the neighborhood to make way for Bellevue Hospital.

The sculpture, which she finished in a new studio downtown, is a monument to the lives upended by the infamous “urban renewal” campaigns of the ’50s and ’60s. Within a few of the crates, you can see elegantly carved table legs, the remnants of what must have once been beloved homes. In a city where gentrification has only accelerated, the sculpture feels like it could have been made yesterday.

MIRA: There were a lot of individual pieces that grabbed me. I was really drawn to “Self-Portrait” by the artist Marisol, a wooden sculpture of seven figures, all attached at the shoulders and brought to life with scraps the artist found on the streets — including human teeth. It felt raw and alive, and combined her South American parentage with her upbringing between Europe, the U.S. and Venezuela.

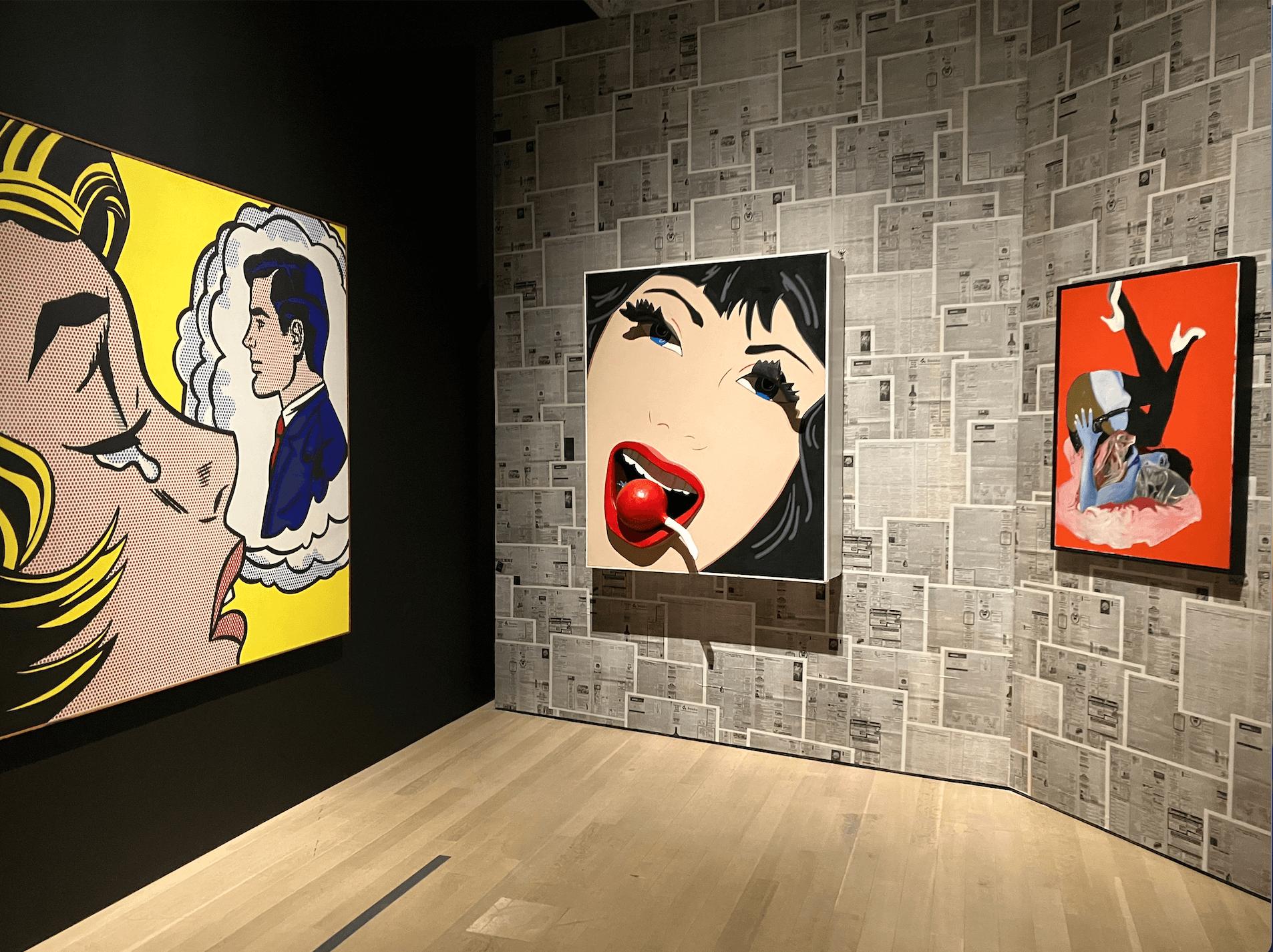

I also loved “Girl with Radish” by Marjorie Strider, a 3D piece showing a woman’s face, her mouth clenched around a red radish and her overly thick eyelashes protruding off the canvas. It’s such a brash yet playful piece that really succeeds at encapsulating the core of Pop Art. And a silver, phallic Yayoi Kusama chair felt kind of random, but whatever — she’s great and I’m always excited to see her work in person.

IRENE: I also loved the archival footage. When I’m presented with film in a public place, I take time to study it in a way I just don’t when watching videos on my computer. I think we both spent a lot of time watching Walter Cronkite’s broadcast after the JFK assassination. There was something really human about the way he kept putting on and taking off his glasses as aides off camera fed him memos and prompter cards with, apparently, different sized fonts.

MIRA: Totally. And I was especially tickled by an ad for Mobil that warned drivers not to speed — because the company needed living customers to buy their oil and gas. What an honest ad!

How did the Jewish Museum originally conceptualize its mandate, and how has that changed? What is a Jewish museum supposed to do, anyway?

MIRA: The Jewish Museum was founded on a collection of Judaica gifted to the Jewish Theological Seminary in 1904. After the Holocaust, it became an especially important as a repository of the Jewish ritual objects and ceremonial pieces left in the wake of the murder of Europe’s Jews. It received Torah crowns and prayer books, filigreed silver mezuzahs and kiddush cups, many of which had been stolen by the Nazis or found in abandoned houses. (I covered an exhibit last year on Nazi looted art that explored this part of the museum’s history.)

But until its first big contemporary exhibition, in 1957, it was not really an art museum. So it must have been a huge shift for it to become a force in the contemporary art world, and it must have been even stranger for people that the museum wasn’t even showing largely Jewish artists under Solomon’s leadership. I’d love to know how that change was received, and I wish the exhibit had said much more about that shift.

IRENE: This kind of goes back to the question of whether the exhibit is Jewish “enough.” In New York, there are basically two kinds of Jewish museums. You have the Museum of Jewish Heritage, which is all about Holocaust memory, and the Tenement Museum, which focuses on immigration in the period of time when most Jews came over. Then there’s the Jewish Museum, which is known for stewarding avant-garde American art but doesn’t have such a distinct lane to stay in. In some ways, this makes it a more exciting place to visit, but it also brings up questions about whether and how much the museum should try to stay “relevant.” If the avant-garde is no longer so connected to Jewish culture, what’s the museum supposed to do?

MIRA: I feel like the Jewish Museum pingpongs between very overtly Jewish exhibits — shows on the Holocaust or retrospectives focusing on Jewish artists — and having only the ghost of a Jewish angle in its exhibits.

But that also makes sense; it’s fittingly parallel to the struggle many American Jews have in understanding their own in-between identity. As Jews in the U.S. have assimilated, it’s become harder to define, exactly, what makes us Jewish — is it facing antisemitism? Is it religious practice? Is it humor, or history, or food?

As far as I can tell, the answer is simply engaging with the question of Jewish identity, and as long as the Jewish Museum continues to grapple with what it means to be a Jewish museum, I think that’s enough.