The delectable tale of the Passover marshmallow, from Egyptian Exodus to American Seder table

Kosher marshmallows are a must on many Seder tables. How did they get there?

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

The menu for Passover desserts is limited; no flour means cakes, cookies and muffins are off-limits unless they’re made with matzo meal or some other, unorthodox — and usually dense — substitute. Because of the lack of options, a few iconic classics have come to dominate the marketplace: canned coconut macaroons, gummy fruit slices and, for some people, marshmallows.

Never heard of marshmallows for Passover? You’re not alone. I posted a hard-hitting kosher-for-Passover marshmallow survey on social media, and a bunch of respondents had never heard of such a tradition. Sure, marshmallows happen to be kosher for Passover — as one respondent pointed out, so is cheese — but they’re not a specific Passover food.

The rest of the responses, however, came from k-for-P marshmallow fanatics. For them, nothing beats a chocolate-covered, Joyva brand k-for-P marshmallow, ideally kept in the fridge or freezer for an iconic snap.

While marshmallows are, of course, a year-round treat, kosher markets explode with them around Passover, stocking giant bins full of options: the classic fluffy white pillows, mini marshmallows for hot cocoa, rainbow swirled ’mallows, and chocolate dipped and coconut coated varieties (to complement your macaroons, of course). Many of the flavors are only available around Passover, and some respondents said kosher ’mallows were only available at all in their area during the Pesach season.

Perhaps this trend developed because marshmallows in general are deeply American. According to the National Confectioners Association, Americans buy the majority of the world’s marshmallows, to the tune of about 90 million pounds a year.

But marshmallows, at least as they’re made today, with gelatin, aren’t kosher at all, much less kosher for Passover. Most gelatin is made from non-kosher animals; the kosher varieties have to sub in a fish-based gelatin as a replacement. Which makes them seem like a pretty goyishe food. But marshmallows, it turns out, are really quite Jewish.

A brief history of the marshmallow

As with Passover itself, it all started in Egypt. The marsh-dwelling mallow plant — yes, the marsh mallow, you get it — had long been used as a medicinal plant by numerous civilizations, including the Romans and Chinese, who used it to treat a wide range of ailments such as sore throats, constipation and low libido. But it was astringent and woody and barely edible; definitely not a treat.

Egyptians created the first marshmallow-like sweets around 2000 B.C.E. by mixing honey, nuts and grains with sap laboriously extracted from the mallow plant; the sap’s thick consistency enabled the confection to congeal into a stable form; the result was reserved for nobility and offerings to the gods. No one truly knows what it was like, but some food historians postulate that it may have been similar to halva, and, indeed, some ancient halva recipes include mallow.

Perhaps the ancient Israelites stole the recipe before they made their way across the Red Sea, but it seems unlikely given the whole too-rushed-to-let-bread-rise thing. Instead, the next leap in marshmallow technology came in France, where whipped egg whites were combined with sugar and mallow extract and then left to dry out, creating a meringue-like confection called pâte de guimauve. It, too, was still sometimes prescribed as a sort of lozenge — a dessert with medicinal applications.

People loved it, but it was far too hard and labor-intensive to meet demand; extracting mallow sap takes something like 12 hours of boiling and straining, you had to hand-beat the egg whites because electricity was not yet a thing, and then the result still had to dry for hours before it could be cut or formed.

Over time, this led to the addition of other ingredients, such as gum arabic as a stabilizer — which was one of the roles the mallow root originally played. This was the first step toward today’s highly processed, corn syrup-filled version, which is devoid of any mallow.

The modern ’mallow

The next marshmallow leap was gelatin. Originally, this was not a great dessert ingredient; it tasted rather like the bones that were used to create it. But then we got unflavored gelatin in the late 1800s and the cheap, flavorless alternative struck the final deathblow to the mallow part of the marshmallow. Around the same time, people figured out how to make marshmallows in starch-covered molds, which allowed them to be manufactured at greater scale and in different shapes. (I’m looking at you, Peeps — which, incidentally, were created by the son of Jewish immigrants, though the chick-shaped marshmallows are not kosher.)

This is more or less when the marshmallow came to America, its true home ever since. There was a massive marshmallow craze in the early 20th century, and marshmallows became a pantry staple. Recipe books, trying to keep up with interest, exploded with overly creative concoctions like marshmallow omelets and marshmallow-topped lima beans. This is also when “marshmallow roasts” — a party for toasting marshmallows over a fire — became popular.

In the 1950s, Alex Doumak of the still-dominant Campfire Marshmallow company invented an extrusion marshmallow manufacturing process, in which a machine forced the marshmallow mixture through tubes, which created a uniform, easy to manufacture shape and allowed the sweet white pillows to be made on a grand scale. Finally, there could be enough marshmallows to go around.

Jews were in on the trend. Amateur historian Rabbi Yael Buechler did some digging for me, and found ads from as far back as 1933 advertising marshmallows to a Jewish audience; a Yiddish spot in Der Tog from the non-Jewish Campfire Marshmallows company promotes marshmallows for Thanksgiving.

But because of the pork-based gelatin, marshmallows weren’t kosher. “Back then, marshmallows were probably seen as an ultimate ‘treyf’ candy,” said Andrew Wachtfogel, who reached out in my survey; he told me that his grandfather, Rabbi David Wachtfogel, was the first to give kosher supervision to marshmallows, which became a “sensation.” In fact, it appears that the Jewish demand for marshmallows was so high that it catalyzed the creation of the kosher fish gelatin they require. It was such a boon to the community that Wachtfogel said he is still approached today by people wondering if he is related to “the marshmallow rabbi.”

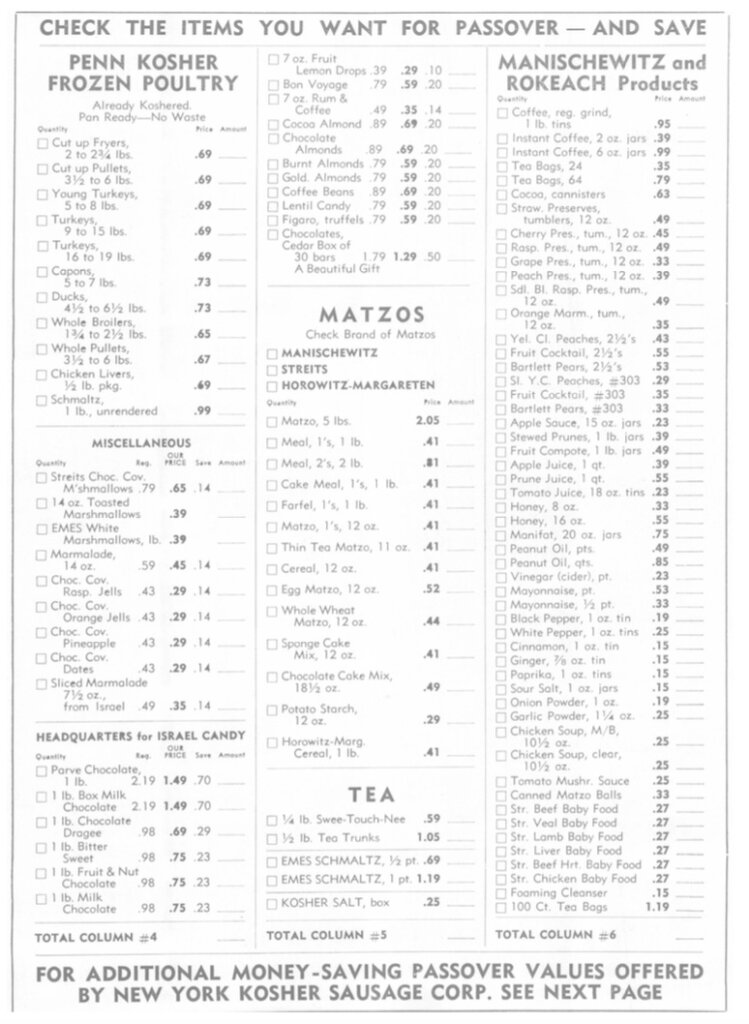

The result was an instant hit. By the late 1950s, when one of the first Passover marshmallow ads appeared, marshmallows had become a Passover treat. Kosher markets boasted about new merchandise for Passover, including chocolate-covered marshmallows. Stores advertised with sample Passover shopping lists, featuring as many as three varieties of marshmallows. Why exactly the confection made the leap from a general sweet treat to a Passover-specific one is unclear — but its place in the Jewish foodscape was secured.

The Passover marshmallow today

For many people, the association of marshmallows with Passover is partially because of availability, though that does raise a chicken-and-egg question of whether Passover-specific demand led stores to stock them for the holiday, or the reverse.

“When I was a kid (’80s and ’90s) there were a lot of foods you couldn’t get kosher most of the year. Marshmallows were one of those,” wrote Ari Elias-Bachrach of Philadelphia. “We could only get them at Pesach time because the local grocery stores would get tons of kosher food brands imported for Pesach.” He added that everyone would stockpile the marshmallows to have enough for summer barbecues as well.

However the marshmallow cart got hitched to Passover, it’s there now. In my survey, Jews from across the U.S. wrote about using the treat as part of their Seder tables, to illustrate the plague of boils, and looking forward to the flavors that were only available at Passover, even if they were generally able to get kosher marshmallows year-round. Others said the general dearth of available foods on Passover led to the sweet treats taking on a particular appeal.

“I had one of those ’70s health-food moms, so candy showing up in the house was a big deal. Marshmallows were never in the house otherwise,” wrote one respondent. “I didn’t even like them that much, but what I did like was that there was candy in the house and I could eat it.”

Today, at least based on the responses to my survey, Joyva dominates the Passover market. The family-owned, Brooklyn-based confectionery is better known for its sesame products, such as halva — in fact, it’s the largest manufacturer of halva in the U.S. But its marshmallows are iconic enough that they have to up manufacturing in November to meet the springtime holiday’s demand.

“Great texture on the Joyva ones. Love the raspberry flavor!” wrote Jacob Devine of Baltimore, Maryland. “As far as I know, my family has been eating Joyva marshmallows for at least three generations.”

Are they good, though? Kosher marshmallows are, unavoidably, a little different than the regular variety. People wrote about storing them in the refrigerator for ideal texture, though they didn’t seem to mind; in fact, a cold marshmallow seems to be their platonic ideal of the form.

Much like the iconic canned macaroons, however, just because something is tradition doesn’t mean it’s beloved. While some people view the marshmallows with warm, holiday nostalgia, the best others could muster was that marshmallows were the best option on Passover, pointing out that the bar is low. Others straight-up said the ’mallows are a plague themselves.

But sometimes, tasting like tradition is more important than a tasty tradition. As one person wrote, “The marshmallows may be gross but that’s just another Jewish family in my book — because Gross is also a Jewish name.”