21 Years Later, A Tel Aviv Mural Pays Tribute To Yitzhak Rabin — And Issues A Warning

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

Elinoy Kisslove is used to receiving odd answers when she asks younger participants in her Tel Aviv graffiti tours what they see in the blurry, black-and-white mural at 26 Florentin Street. “The universe,” someone said to her once. “A womb,” suggested another.

Those who live near the mural – mostly 20-somethings attracted to the gentrifying neighborhood’s low rents and artsy vibe – also have a hard time identifying the image. At 21 years old, the mural itself is roughly the same age as many of Florentin’s residents.

Yet the older participants in Kisslove’s tours recognize the image almost immediately.

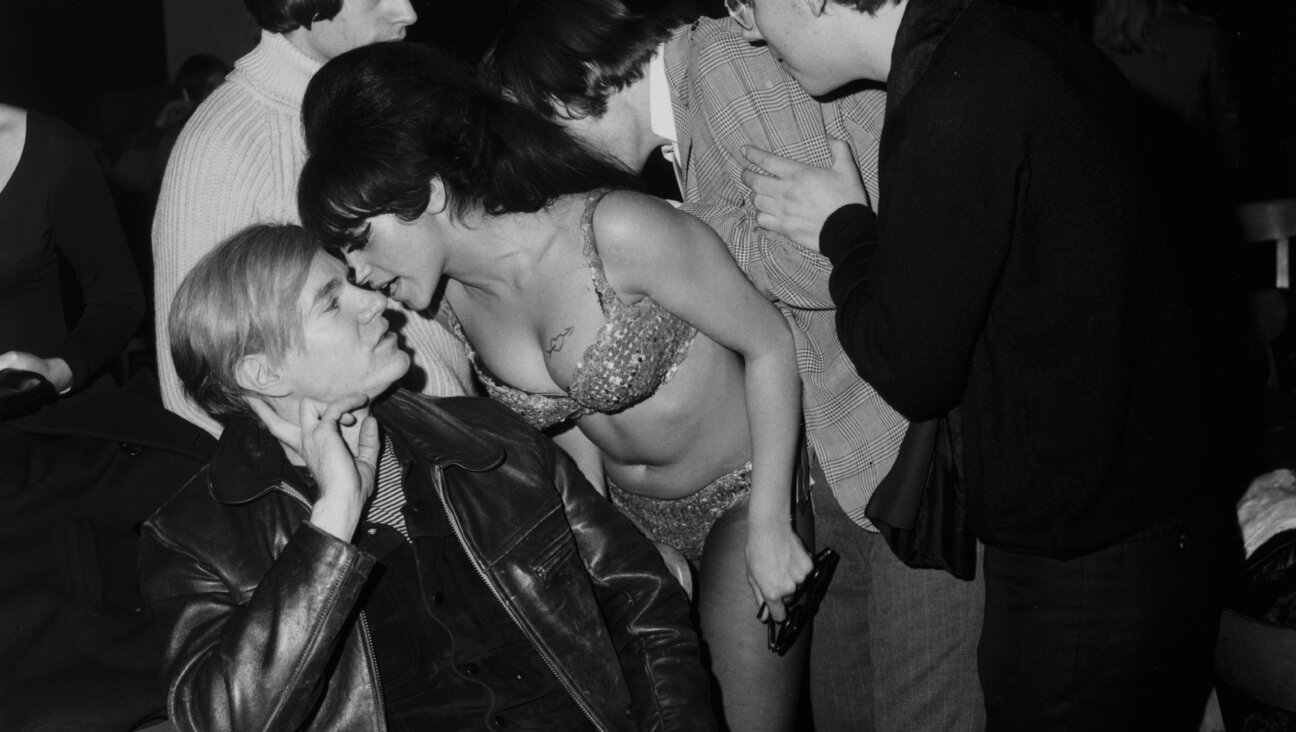

Painted over the course of a few midnight hours in the early fall of 1996 by local artist and political activist Yigal Shtayim, the mural recreates a frame from the only existing footage of the assassination of Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin on November 4, 1995. Filmed accidentally by professional accountant and amateur photographer Roni Kempler, the footage was used as evidence in the trial of Rabin’s assassin, Yigal Amir, and was first aired to the public in a news broadcast in December 1995. White arrows single out the two key figures: Rabin and Amir.

Millennials might primarily associate Rabin with the official portrait of him as Prime Minister, the photograph of his first public handshake with Yasser Arafat after signing the first Oslo Accord – part of an effort that would win Rabin, Arafat, and Shimon Peres a Nobel Peace Prize – or black-and-white images of him as a 26-year-old soldier during the Six Day War.

Yet this particular monochrome image, apparently, isn’t as familiar.

To Shtayim, the image epitomizes what we should take from the Rabin assassination. “I chose this specific image from a newspaper illustration that used arrows to explain what had happened at the time of the murder,” Shtayim wrote in an email last week. “My selection was intended to commemorate the moment of the murder, as a way to immortalize the social threat that was prevalent at that time – the dangers of extremism and incitement.”

“I preferred a warning sign, a confrontation with the difficult and traumatic moment, instead of fond remembrances of Rabin’s portrait, or other moments of grace,” Shtayim says.

For those that can identify it, the image is a painful reminder of a threat from within: Rabin was assassinated by an Israeli Jew, not an external enemy. It is so uncomfortable, in fact, that there have been two attempts to cover it up.

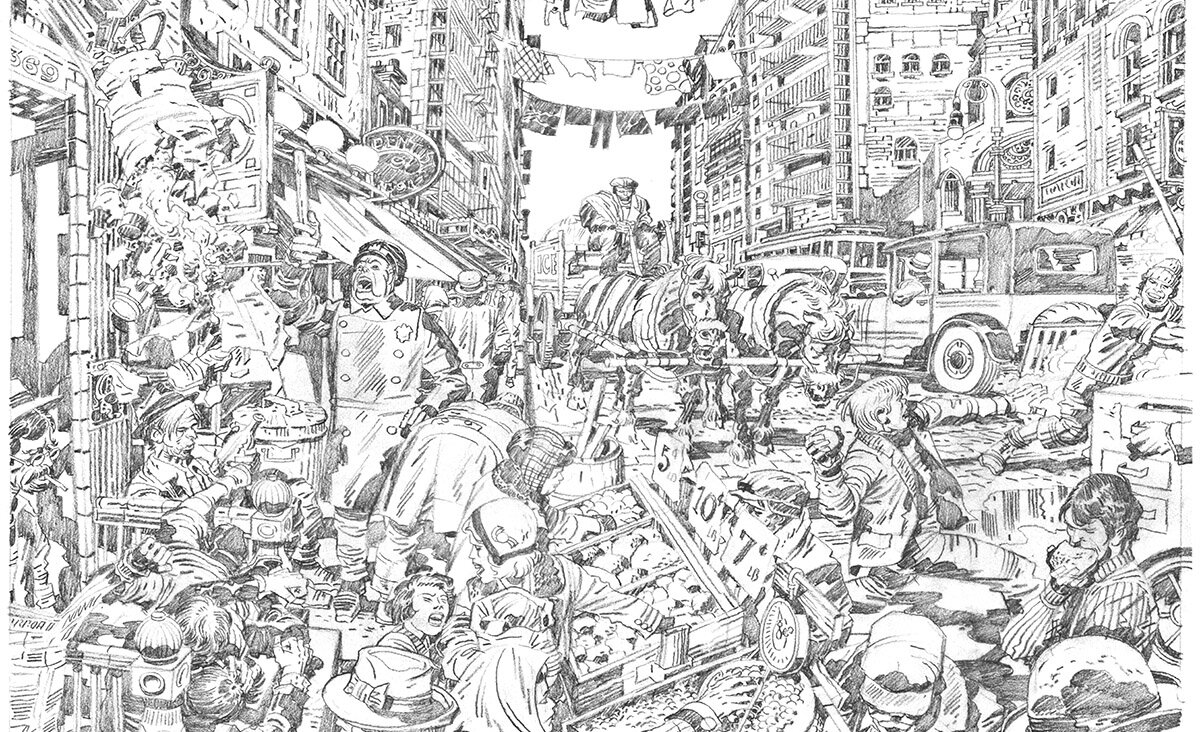

The first of these instances took place on October 18, 1996, just weeks before the first anniversary of the assassination, when painted wooden boards depicting an oversized pink horse galloping through an urban landscape were installed above Shtayim’s mural. An illustrated article published a few days later in the Israeli newspaper Maariv quoted a Tel Aviv municipality representative as claiming that the boards were placed there temporarily during a craft fair.

The residents of Florentin protested, and the city uncovered the mural. Kisslove, who currently lives one block away from the artwork and remembers seeing it as a child, said of witnessing the residents protesting the mural’s erasure, “That’s the moment I understood that graffiti can make history.”

Shtayim was far from the only artist to commemorate Rabin’s assassination. In the former Kings of Israel Square, now called Rabin Square, where Rabin was assassinated, thousands of mourning Israelis from all over the country wrote layers of grieving messages on the walls of City Hall and the peripheries of the five-acre square, the largest paved public space in Tel Aviv.

Mira Engler, a professor of landscape architecture at Iowa State University who researched the post-assassination graffiti, wrote in a 1999 academic paper published in Places Journal that “the graffiti were created by thousands of individuals but seemed a coordinated piece, like a concert conducted by an invisible maestro.” The walls were documented in two books of photographs.

The Tel Aviv municipality discussed options for preserving the graffiti but ultimately painted over most of the text without notice in January 1997. A remnant was left near the city-sponsored monument to Rabin: “Sorry,” reads one Hebrew message in large, blue letters, next to pasted images of Rabin and the message “Friend, you are missed.”

Shtayim’s mural remained. In a neighborhood saturated with enough street art to warrant multiple graffiti tours, it is surprising that the mural has been left untagged and untouched by Florentin’s many visual artists.

“I don’t think [street artists] care about it at all, actually,” said street art historian Yael Shapira of Alternative Tel Aviv Tours. “I believe that, like myself, they don’t really consider it as part of the artistic genre that they practice.”

Kisslove, who lives in Florentin and has been guiding graffiti tours there since 2012, believes the opposite. “If it’s still there,” she says, “it’s because it has a lot of respect on the street.”

The anniversary of Rabin’s assassination falls on a Saturday this year, a night on which many Florentin residents can usually be found at Bugsy, the bar a few steps from the mural. On busy nights, when the tables occupying the ground level floor of Bugsy’s Bauhaus-style building fill up, patrons spill over to a few umbrella-covered tables in the middle of the adjacent pedestrian boulevard.

Their eyes might be drawn to the colorful collaborative artwork added below Shtayim’s mural in March 2016 by local artists Zeev Engelmayer and Oren Fischer. Engelmayer and Fischer’s colorful, graphic figures are an attractive backdrop to the selfies that often follow a drink or two. The Guinness-emblazoned umbrellas overhead block guests’ views of the political past, cocooning them in a carefree Florentin of the present.

Correction, November 6, 1:35 pm: A previous version of this article stated that Yitzhak Rabin was 26 at the time of the Six-Day War; he was in fact 45. That same version stated that the Tel Aviv Museum of Art hosted an exhibit dedicated to the graffiti in what is now Rabin Square memorializing Rabin following his assassination. That exhibit was not hosted by that museum.