Who Are The Hebrew Israelites?

Image by Sam Kestenbaum / Forward Association

Updated December 11, 2019

Their story rarely finds its way into the mainstream news. When it does, readers are surprised.

A cousin of First Lady Michelle Obama is a black rabbi in Chicago? Generations of African Americans — not religious converts — who observe the Sabbath and read the Torah? A star NBA player decides to move to Jerusalem on a spiritual journey, calling himself the descendent of an “ancient tribe of the Hebrew Israelites?” What does it mean?

Parallel to the American Jewish story, another complex spiritual tale has been unfolding for over a century — that of the Hebrew Israelites.

Rabbi Matthew, second from left at table, founder of the Commandment Keepers, leading a Passover seder in 1941. Image by Forward Association

Who are Hebrew Israelites?

Hebrew Israelites are people of color, mostly African Americans, who view the biblical Israelites as their historic ancestors. For Hebrew Israelites, the transatlantic slave trade was foretold in scripture and they understand those Africans who were enslaved in the Americas as Israelites, severed from their heritage. Now they are returning.

Israelites of all stripes today point to specific scriptures as prophetic proof of their ancestry, particularly Deuteronomy 28. For Israelites, the chapter describes a foretelling of slavery and servitude in the Americas: “The Lord will send you back in ships to Egypt on a journey I said you should never make again.” The chapter also describes those Israelites being made to serve false gods and lose knowledge of their true identities.

How old is the movement?

Over a century. There is no one “founder” of the movement, instead an entire generation of patriarchs who shared related beliefs. These figures were commonly called Black Jews in their lifetimes, but later generations carrying on their traditions have gravitated towards Hebrew Israelite or simply Israelite.

These patriarchs include a former runaway slave named William Saunders Crowdy, who gained a following in the 1890s, teaching that blacks were the “lost sheep of Israel” and that they should return to the ancient ways of the Hebrews as described in the bible.

In New York, a Barbadian musician named Arnold Josiah Ford founded a Harlem congregation in 1924 and also taught that blacks should take on the Hebrew faith. Ford was an associate of nationalist leader Marcus Garvey and led a small group of followers to Ethiopia in 1930 where he lived until his death.

Arguably the most influential leader was another Caribbean-born rabbi named Wentworth Arthur Matthew, who was ordained by Ford. Matthew founded an influential congregation in Harlem known as the Commandment Keepers in 1919. That congregation became a hub of high-profile activity for decades, visited frequently by Jewish journalists (including reporters from the Yiddish Forverts). Matthew formed a rabbinical school and taught an entire generation of spiritual leaders.

More details about the formative years of these groups can be found in the book “Chosen People,” by Jacob Dorman, a professor of history at Kansas University. For a perspective from the Israelite Board, Rabbi Sholomo Ben Levy maintains a website, with many pages of insider history, about “people who identify as Black Jews or Israelites.”

Why ‘Israelites’ and not Jews?

From around the the 1890s to the mid 1960s, the leaders mentioned above were most commonly called Black Jews. Beginning in the mid 1960s, a younger generation of community members ushered in the term Hebrew Israelite.

Distinction: “Israelites and Jews: The Significant Difference,” a book published in 1997 by Cohane Michael Ben Levi makes a clear distinction between the religious practices of Judaism and the traditions of the Hebrew Israelites.

The term Hebrew Israelite, or often simply Israelite, is used today by members to distinguish themselves from the religion practiced by Ashkenazi, Sephardi or Mizrachi Jews. Israelites maintain that they are practicing their ancestral way of life, not coming into a foreign religion. Still, there has long been a debate about what terms to use.

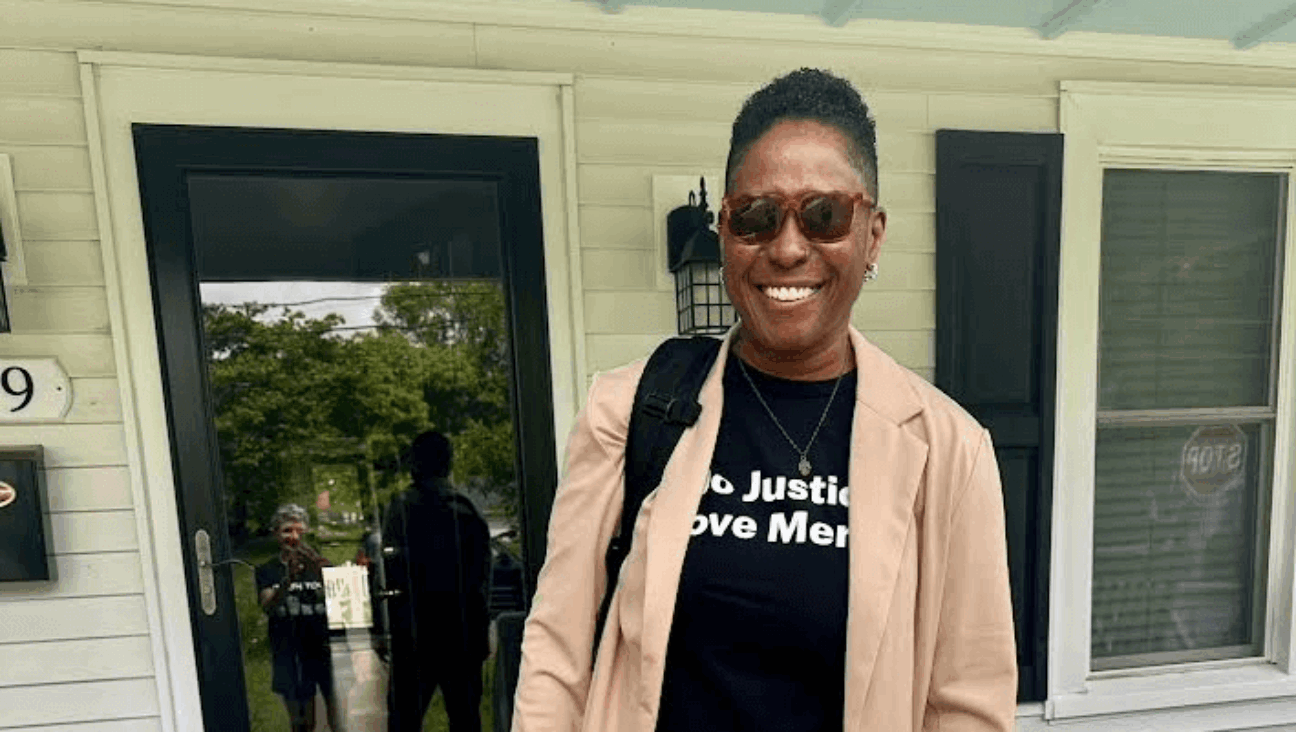

And categories are never static. Hebrew Israelites may also identify as Jews and move fluidly between Israelite and Jewish prayer spaces or organizations. Take, for example, Rabbi Capers Funnye, who holds an Israelite ordination and also attended the mainstream Spertus Institute for Jewish Learning and Leadership. Funnye has said that, to him, the terms Black Jew, Hebrew Israelite and Black Hebrew are all synonymous — and simply mean “Jew of African descent.”

What are those biggest groups today?

The International Israelite Board of Rabbis was founded in 1970 by a group of Rabbi Matthew’s students. The newly-elected chief rabbi of the board is Funnye, a cousin to Michelle Obama and a well known cleric from Chicago.

The Church of God and Saints of Christ, organized by Crowdy, is another very large group which also teaches the New Testament and calls Jesus Christ a prophet. A new chief rabbi has recently been named for this organization, which is based in Virginia.

A third well-known group, originally based in Chicago, Illinois, is the African Hebrew Israelites of Jerusalem, formerly led by a man known as Ben Ammi. This group caused international headlines when they left America and ultimately settled in Dimona, Israel, starting in 1969. The have had a fraught relationship with the Israeli government for decades, but relations have improved in recent years.

Ben Ammi Ben Israel, whose followers left Chicago and settled in Israel beginning in 1969. Image by YouTube

Another high-profile category of Hebrew Israelites preachers have their origins in a teacher called Abba Bivens, a former member of the Commandment Keepers who formed a school of his own in Harlem in the 1960s. Collectively, they are widely known as 1 West camps, taking the name from the Harlem street address of Bivens’ original school. Bivens’ disciples splintered into many different groups with varying doctrines over the decades. In general, they teach that those called Jews today are imposters and usurpers of Israelite tradition. These Israelites have perhaps the most public presence today and are recognizable by their colorful garb and confrontational street corner preaching.

Where are they?

Everywhere. New York, Chicago, Virginia, Atlanta and Philadelphia have been historic hubs and there are Israelite outposts in the Caribbean and also in Africa. Individuals may also self-identify as a Hebrew Israelite without officially belonging to one branch or congregation. The Internet has also contributed to an active online community, which can be geographically diffuse.

Are they ‘recognized’ by other Jews?

That depends on what “recognized” means. Most Israelites are not looking for validation or recognition and in fact may not identify as Jews. Still, some Jewish American groups have sought to bring Israelites into the fold — but often suggest conversion, which many Israelites object to.

Some of those early efforts at outreach also failed to distinguish the Israelites from Jews of color who belong to mainstream denominations. And some African American Jews have been among sharpest critics of the Hebrew Israelites, both historically and in recent months.

Rabbi Capers Funnye is the spiritual leader of Beth Shalom Bnai Zaken Ethiopian Hebrew Congregation in Chicago. Image by Sam Kestenbaum

Under the leadership of Rabbi Funnye, however, the topic of engagement with American Jewry and the State of Israel has again come to the fore for some Israelites. Funnye holds an Israelite ordination but also converted in a Conservative beit din. He also sits on the Chicago Board of Rabbis. Now chief rabbi of the International Israelite Board of Rabbis, Funnye has asked member congregations of the board to support the State of Israel and to reach out to other Jews. Still, this is not to seek validation — Funnye emphasizes — but to seek common ground.

When else have Hebrew Israelites been in the news?

A group of high school students from Kentucky visiting Washington, D.C. went viral in January 2019 after a video was published of them yelling at a Native American activist at the Washington Monument. The teens claimed that the fight had been instigated by Hebrew Israelites who had screamed abuse at them, though members of the group said that they were being used to distract from the teens’ misbehavior.

One of the gunmen who allegedly attacked a kosher grocery store in Jersey City, New Jersey in December 2019 was reportedly a former member of a Hebrew Israelite group.

Read more about these diverse communities:

Email Sam Kestenbaum at [email protected]

Aiden Pink contributed reporting.