Nazi collaborator monuments in Canada

Edmonton, Alberta is home to a bust of Nazi collaborator Roman Shukhevych

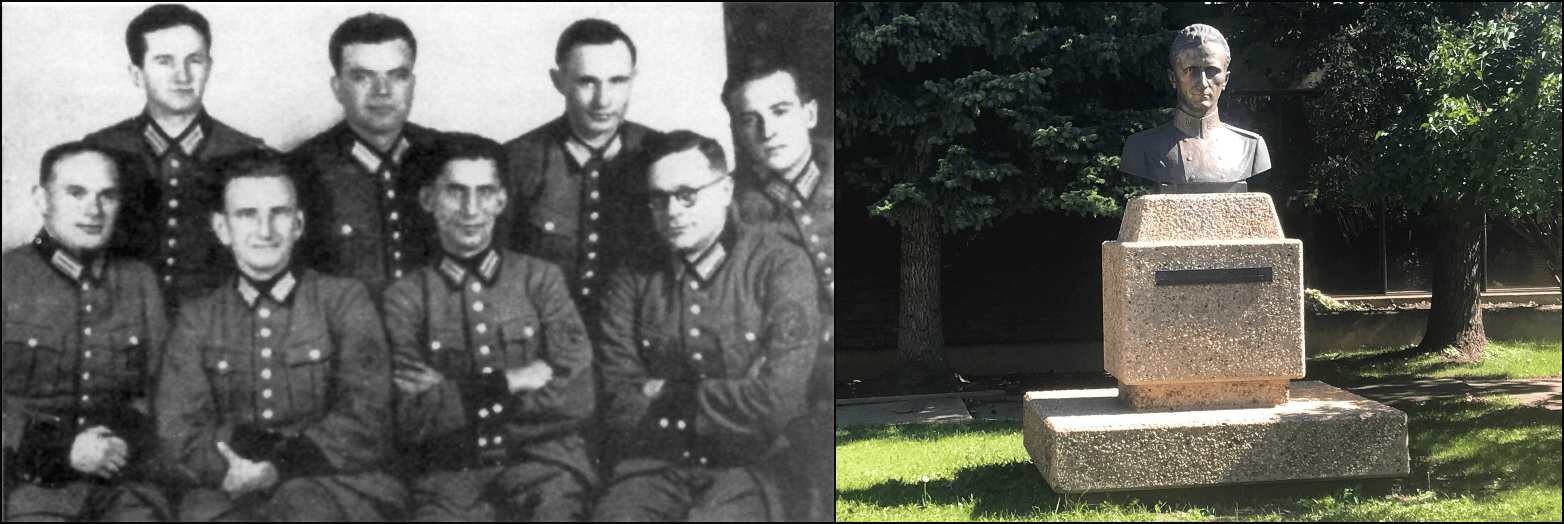

Left: Roman Shukhevych, sitting, second from left, among officers of the 201st Schutzmannschaft Battalion, 1942 (Wikimedia Commons). Right: Shukhevych bust outside the Ukrainian Youth Unity Complex, Edmonton (Duncan Kinney/theprogressreport.ca). Image by Lev Golinkin

This list is part of an ongoing investigative project the Forward first published in January 2021 documenting hundreds of monuments around the world to people involved in the Holocaust. We are continuing to update each country’s list; if you know of any not included here, or of statues that have been removed or streets renamed, please email [email protected], subject line: Nazi monument project.

Monuments to French collaborators

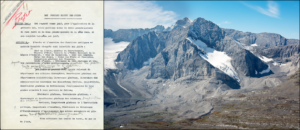

Update (January 2023): Pétain’s name was dropped from Mount Pétain and the nearby glacier and creek in June 2022 after a six-year campaign by Geoffrey and Duncan Taylor.

Border of Alberta and British Columbia and Nova Scotia — Mount Pétain in the Canadian Rockies, named after French collaborator Philippe Pétain (1856–1951) who led the Vichy Regime which deported around 76,000 Jews to their deaths.

Pétain was once a WWI hero; the peak was named in his honor in 1918, long before he became a traitor. Landscape features around the mountain — Pétain Glacier, Pétain Basin, Pétain Creek and Pétain Falls — are named after him as well. Canada also has Petain Station Road in Nova Scotia. (Thanks to David P. Jones for the use of his photo of Mt. Pétain.)

Above left, Pétain’s annotations on Vichy anti-Jewish laws, a crucial step on the way to dehumanizing and eventually deporting France’s Jews. In 2018, the French government caused a scandal after announcing plans to honor Pétain. After the backlash, Paris cancelled the events, yet the fact that a major Western nation planned to honor a traitor whose regime participated in the Holocaust is a disturbing sign.

Below left, Pétain with Hitler, 1940; below right, Pétain on trial for treason, 1945.

For more locations named after Pétain and debates over his honors, see the U.S. section.

Monuments to German collaborators (section added July 2025)

London, Ont. – A street honoring Max Brose (1884–1968), Nazi Party member whose automotive company in Coburg, Germany used slave labor during World War II; some of the slaves, which included prisoners of war, were used to produce supplies for the German armed forces. Brose himself was appointed Wehrwirtschaftsführer (economic leader), a title given to business tycoons behind the Third Reich war machine. Above left, Brose in Nazi uniform.

The street bearing Brose’s name is located near the Canada branch of his company, today called Brose Fahrzeuge. The firm has been rehabilitating Brose’s image into that of an industrial titan who deserved to be celebrated. In 2015, Brose’s billionaire grandson, who is the CEO of Brose Fahzeuge, successfully lobbied to have a street named in the company’s global headquarters in Coburg. This was done despite the vociferous protests from Germany’s largest organized Jewish community.

A spokesperson for London confirmed the street naming was initiated by Brose Canada, Inc.

Many nations have laws against glorification of Nazism. It’s unclear whether naming a street for a known Nazi Party member violates Canadian law.

There are seven Max Brose streets around the world, each one located in a town that houses a Brose Fahrzeuge division. See the Brazil, Germany, Mexico and Slovakia sections for more Brose streets. Below, Nazi parade marches through Coburg in 1933.

See coverage in the Financial Times, Focus Online (Google translation here), inFranken.de (Google translation here) and Süddeutsche Zeitung (Google translation here and here). See New York Times coverage of an art world scandal regarding the Nazi fortune of Broze’s great-granddaughter.

Monuments to Serbian collaborators

Hamilton, Ont. and Stoney Creek, Ont. — A statue of Dragoljub “Draža” Mihailović (1893–1946) leader of the Chetniks, a Serbian nationalist and Yugoslavian royalist militia which collaborated with the Nazis and their Serbian puppets. At another point during the war, Mihailović cooperated with the Allies, using his troops to help rescue over 400 American airmen shot down in enemy territory. There’s also a community center named after him in Stoney Creek.

Above is Mihailović (center) with his commanders in 1943. (Many thanks to Milijana Pavlović for aid in locating Chetnik statues outside Serbia.)

For more Chetnik monuments, see the Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, U.K., U.S. and Australia sections.

(Note: The Stoney Creek center was added July 2025.)

Monuments to Ukrainian collaborators

Edmonton, Alta. — A bust of Nazi collaborator Roman Shukhevych (1907–1950), a leader in a Third Reich auxiliary battalion involved in lethal antisemitic violence and anti-partisan suppression. Shukhevych also led the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA), which massacred thousands of Jews and 70,000-100,000 Poles. On the left is Shukhevych (sitting, second from left) among the commanders of the Third Reich auxiliary police battalion in 1941–1942.

Shukhevych’s bust is outside Edmonton’s Ukrainian Youth Unity Center; the center’s lobby contains a bas-relief of Shukhevych and signs for the UPA and the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN), a Nazi collaborator group. The UPA was the paramilitary arm of an OUN faction. (Thanks to Duncan Kinney of Progress Alberta for the monument photo. Thanks also to Per Anders Rudling for his invaluable advice and encyclopedic knowledge about both the collaborators and the history of Canada’s monuments.)

(Note: The bas-relief and OUN and UPA signs were added January 2023.)

Update (March 2024): the monument has been removed from St. Volodymyr’s Ukrainian Cemetery, where it stood; the cemetery announced it “would not permit this monument to be returned.”

Oakville, Ont. — A monument to the 14th Waffen Grenadier Division of the SS (1st Galician) aka SS Galichina. Above left is an SS Galichina ceremony in 1943–1944; note the division’s lion and crowns insignia which is also found on the monument.

This pillar honoring SS fighters has been at the center of 2020’s debate over Nazi collaborator statues in Canada. The scandal began when the monument was vandalized and local police initially declared the vandalism to be a “hate crime,” meaning the Waffen-SS were the victims (see end of section for more information).

Oakville, Ont. — A monument honoring the Ukrainian Insurgent Army paramilitary led by Roman Shukhevych. On the left is Shukhevych (far left) in 1943, when the UPA carried out a campaign of ethnic cleansing, systematically slaughtering 70,000-100,000 Poles. The paramilitary also killed thousands of Jews. Due in part to the actions of local collaborators in militias and Nazi auxiliary police units, a quarter of all Jews killed in the Holocaust were from Ukraine.

Edmonton, Alta. — A Ukrainian war veterans’ memorial in honor of the UPA and SS Galichina, among other groups. Above left is an SS Galichina recruitment poster calling on Ukrainians to fight alongside “the finest warriors in the world.” (Thanks to Duncan Kinney of Progress Alberta for the monument photo.)

In 1997, Canada admitted to taking in 2,000 Ukrainian SS Galichina soldiers after WWII. Below, Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler, the head of the SS and one of the chief architects of the Holocaust, meets to inspect and rally SS Galichina troops on May 6, 1944 in Neuhammer (now Świętoszów), Poland.

***

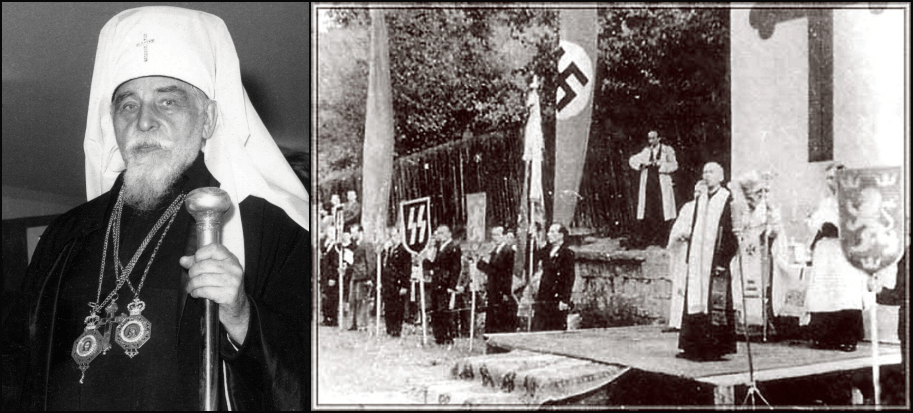

Toronto (entry added January 2022) – The city has a Catholic elementary school named for Iosif Slipyi (1892–1984), archbishop in the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church. In 1941, Nazi Germany invaded Ukraine, kicking off a series of pogroms that would lead to the annihilation of 1.5 million Jews thanks to the Nazis and their willing collaborators. Slipyi was part of a self-proclaimed government that pledged allegiance to Hitler.

In 1943, the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church played an important role in the creation of SS Galichina (see earlier entries). Slipyi coordinated the church’s aid to the Waffen-SS – he not only assigned chaplains to the unit but personally celebrated mass at the division’s official creation. SS Galichina went on to commit war crimes such as the Huta Pieniacka massacre.

In 1983, forty years later, Slipyi praised SS Galichina when commemorating the division’s founding. “Let the memory of Ukrainian Galichian Division live with us forever as a testament to nations that we strive for freedom, statehood and are prepared for the greatest sacrifices for truth, fairness and peace to be in our land,” he proclaimed, calling on the faithful to pray for SS men. Above right, Waffen-Sturmbannführer Vasyl Laba, the head chaplain of SS Galichina, conducting services.

See the Italy, Ukraine and U.S. sections for more Slipyi glorification. See the JTA on Nazi symbols that are a regular part of SS Galichina commemorations, condemnations from the German ambassador to Ukraine and the Israeli foreign ministry, and the AP on a former SS Galichina officer in the U.S.

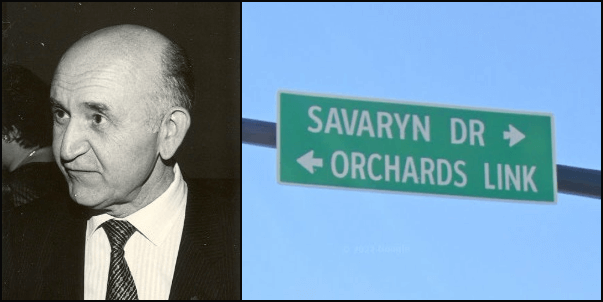

Edmonton, Alta. (entry added July 2025) – a street honoring Peter Savaryn (1926–2017), lawyer and ex-chancellor of the University of Alberta who served in SS Galizien (aka SS Galichina). In 2023, the Forward broke the news that the Governor General of Canada (the representative of King Charles III) apologized for the British Crown awarding Savaryn two medals.

Later in life, Savaryn carefully crafted his image to make it appear he was a victim of the Nazis. In a 2004 Edmonton Journal interview, he spoke of escaping a Gestapo raid and fleeing Ukraine; the article neglected to mention that in the intervening years, he served the Third Reich.

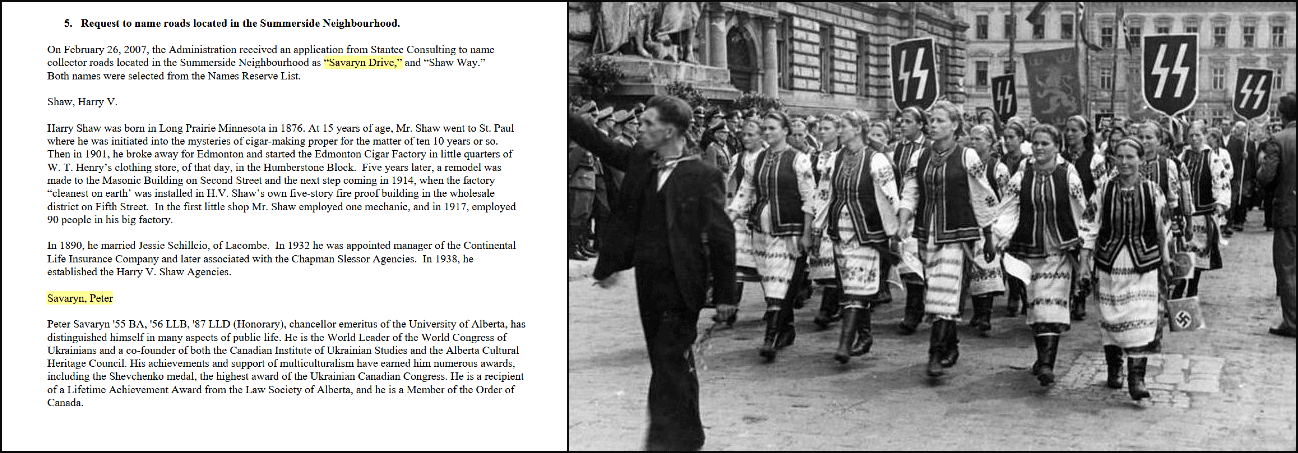

Savaryn Drive doesn’t have Peter Savaryn’s first name. However, agenda from a 03/28/07 meeting of Edmonton’s Naming Committee, below left, lists Savaryn’s full name and biography, making it clear who it’s named after. The biography stresses Savaryn’s commitment to “multiculturalism,” which is ironic given his SS background. Below right, SS Galizien recruits parade in front of a review stand containing Nazi higher-ups, L’viv, 1943.

For Ukrainian Nazi collaborator monuments outside of Canada, see the Ukraine, U.S., Argentina, Germany, U.K., Italy, Austria and Australia sections.

For more on Canada’s monuments, see this academic paper by Prof. Per Anders Rudling of Lund University; coverage in the Ottawa Citizen, Espirit de Corps, and The Nation; Simon Wiesenthal Center condemnation; B’nai Brith Canada’s press release condemning the monuments; and Defending History’s page on the 2020 debate.