Nazi collaborator monuments in Ukraine

Many new streets and monuments have been erected since a new government took over in 2014

Left: parade honoring Third Reich Governor-General of Poland Hans Frank, Stanislaviv (now Ivano-Frankivsk), October 1941 (Wikimedia Commons). Right: march commemorating the establishment of the 14th Waffen Grenadier Division of the SS (1st Galician), L’viv, April 28, 2014 (Yuri Dyachyshyn/AFP via Getty Images). Image by Forward collage

This list is part of an ongoing investigative project the Forward first published in January 2021 documenting hundreds of monuments around the world to people involved in the Holocaust. We are continuing to update each country’s list; if you know of any not included here, or of statues that have been removed or streets renamed, please email [email protected], subject line: Nazi monument project.

Note: In the years since the Maidan uprising brought a new government to Ukraine in 2014, numerous monuments to Nazi collaborators and Holocaust perpetrators have been erected, at times as frequently as a new one each week. Due to the overwhelming number of streets named after Stepan Bandera and Roman Shukhevych, only some are listed as part of this project.

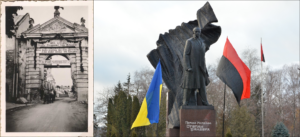

L’viv and Ivano-Frankivsk — 1.5 million Jews, a quarter of all Jews murdered in the Holocaust, came from Ukraine. Over the past six years, the country has been institutionalizing worship of the paramilitary Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists, which collaborated with the Nazis and aided in the slaughter of Jews, and the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA), which massacred thousands of Jews and 70,000-100,000 Poles. A major figure venerated in today’s Ukraine is Stepan Bandera (1909–1959), the Nazi collaborator who led a faction of OUN (called OUN-B); above are his statues in L’viv (left) and Ivano-Frankivsk (right). Many thanks to Per Anders Rudling, Tarik Cyril Amar and Jared McBride for their guidance on Ukrainian collaborators.

Ternopil and numerous other cities — Another statue of Bandera in Ternopil. Above left is a photo from Zhovkva in 1941, when OUN members welcomed the Nazis, assisting with their murder of Jews. The banners include “Heil Hitler!” and “Glory to Bandera!”

Ukraine has several dozen monuments and scores of street names glorifying this Nazi collaborator, enough to require two separate Wikipedia pages (there are so many Bandera streets that only a few are listed in this project). These include:

- joint monuments to him and Roman Shukhevych in Cherkasy, Horishnie (Novorozdilʹsʹka Misʹka Rada), Pochaiv, Rudky and Zaviy;

- a monument to him, Shukhevych and other OUN leaders in Morshyn;

- a monument to him and his father in Pidpechery;

- a plaque and monument in Lutsk;

- a bas-relief, monument and museum in Dubliany;

- a plaque, monument and museum (with bust) in Stryi;

- a plaque, street and monument in Zdolbuniv;

- monuments in Berezhany, Boryslav, Buchach, Chervonohrad, Chortkiv, Drohobych, Dubno, Hordynya, Horodenka, Hrabivka (Ivano-Frankivsk Raion), Kalush, Kamianka-Buzka, Kolomyia, Kozivka, Kremenets, Krushel’nytsya, Kyiv, L’viv, (and a plaque), Mlyniv,Mostyska, Mykolaiv (L’viv Oblast), Mykytyntsi, Nyzhnye (Sambir Raion), Pidvolochysk, Romanivka, Sambir, Skole, Sniatyn, Staryi Sambir, Seredniy Bereziv, Sokal, Sosnivka, Strusiv, Tatariv, Terebovlia, Truskavets, Turka, Uzyn, Velyki Mosty, Verbiv (Narayiv Hromada), Zahirochka and Zalishchyky;

- a plaque and street in Sniatyn and Zhytomyr;

- plaques in Ivano-Frankivsk, Khmelnytskyi, Rivne and Rohatyn.

- museums in Staryi Uhryniv (with a statue and memorial plaque) and Volya-Zaderevatska (with a bust and bas-relief);

- a park in Kamianka-Buzka;

- a street in Dnipro; and a school in Dobromyl.

(Note: The Dnipro and Tatariv honors were added October 2022; the Rohatyn plaque was added June 2025.)

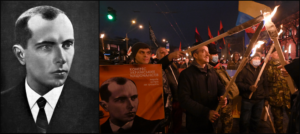

Left: Stepan Bandera (Wikimedia Commons). Right: Far-right march in honor of Bandera’s 112th birthday, Kyiv, January 1, 2021 (Genya Savilov/AFP via Getty Images).

Kyiv — In 2016, a major Kyiv boulevard was renamed after Bandera. The renaming is particularly obscene since the street leads to Babi Yar, the ravine where Nazis, aided by Ukrainian collaborators, exterminated 33,771 Jews in two days, in one of the largest single massacres of the Holocaust. Both the Simon Wiesenthal Center and the World Jewish Congress condemned the move.

Above right, the annual torchlight march on Bandera’s birthday in 2021; during the 2017 commemorations marchers chanted “Jews Out!”

Krakovets, L’viv and numerous other towns — Monuments to Roman Shukhevych (1907–1950), another OUN figure and Nazi collaborator who was a leader in Nazi Germany’s Nachtigall auxiliary battalion, which later became the 201st Schutzmannschaft auxiliary police unit. Shukhevych later commanded the brutal Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA), responsible for butchering thousands of Jews and 70,000-100,000 Poles.

The monument in Krakovets (above left) and plaque in L’viv (above right) are two of many Shukhevych statues in Ukraine. This includes joint monuments to him and other nationalists in several cities (see Bandera entry above) a monument to him and other nationalists in Sprynya; a monument, two plaques and a bas-relief in L’viv Polytechnic National University in L’viv; and monuments in Borschiv, Ivano-Frankivsk, Kalush, Khmelnytskyi, Khust, Kniahynychi, (and a plaque), Kolochava, Ohlyadiv, Shman’kivtski, Staryi Uhryniv (at the Stepan Bandera museum), Tyshkivtsyah, Tyudiv, and Zabolotivka; plaques in Buchach, Kamianka-Buzka, Kolomyia, Pukiv, Radomyshl’, Rivne and Volya-Zaderevatska; a museum in Hrimne; a stadium in Ternopil; a metro station in Kyiv; and a school in Ivano-Frankivsk. See The Algemeiner on Israel slamming naming the Ternopil stadium for Shukhevych.

Even more shocking are the Shukhevych monuments in Canada and the U.S.

Additionally, Shukhevych is honored with several dozen streets in Ukraine (there are so many that only a few are listed in this project). Most of the Bandera and Shukhevych statues are in western Ukraine, in towns where the Jewish population was exterminated by paramilitaries loyal to these men. A major boulevard has been named for Shukhevych in Kyiv as well. The World Jewish Congress condemned the glorification of Shukhevych and the statue in Ivano-Frankivsk.

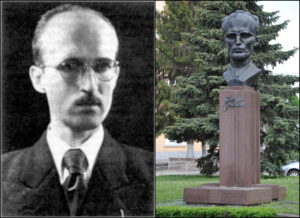

Ternopil — A bust of the genocidal Yaroslav Stetsko (1912–1986), who led Ukraine’s 1941 Nazi-collaborationist government which welcomed the Germans and declared allegiance to Hitler. A rabid antisemite, Stetsko had written “I insist on the extermination of the Jews and the need to adapt German methods of exterminating Jews in Ukraine.” Five days prior to the Nazi invasion, Stetsko assured OUN-B leader Stepan Bandera: “We will organize a Ukrainian militia that will help us to remove the Jews.”

He kept his word — the German invasion of Ukraine was accompanied by horrific pogroms with the incitement and eager participation of OUN nationalists. The initial L’viv pogrom alone had 4,000 victims. By the war’s end, Ukrainian nationalist groups massacred tens of thousands of Jews, both in cooperation with Nazi death squads and on their own volition.

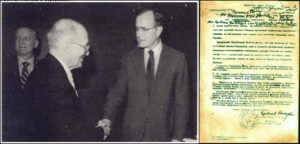

Stryi and 18 other locations — Additional Stetsko monuments are found in Stryi (above left), which also has a Stetsko street, Velykyi Hlybochok (above right), which also has a Stetsko museum (with plaque) and school, Kam’yanky and Volya Zaderevatska. Stetsko also has a joint monument to him and other OUN leaders in Morshyn and streets in Bucha, Dnipro, Dubno, Horodok (Khmelnytskyi Oblast), Khmelnytskyi, Lutsk, L’viv, Mezhrychichya (Sheptytskyi Raion), Monastyrys’ka, Pervomaisk (Mykolayiv Oblast), Rivne, Rudne, Sambir and Ternopil. After the war, Stetsko — the man who formally pledged his government’s loyalty to Hitler — moved to the U.S., where he quickly rose into the highest circles of Washington. He was lauded as leader of freedom fighters by Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush.

Below left, Stetsko meeting with then-Vice President Bush, 1983. Below right, Stetsko’s signature on the Proclamation of Ukrainian Statehood with a pledge to “work closely with National-Socialist Greater Germany under the leadership of Adolf Hitler.”

(Note: The Bucha, Dnipro, Horodok (Khmelnytskyi Oblast), Mezhrychichya (Sheptytskyi Raion) and Pervomaisk (Mykolayiv Oblast) streets were added June 2025.)

***

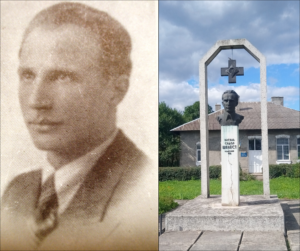

L’viv and two other locales — A memorial plaque to Dmytro Paliiv (1896–1944), co-founder and Waffen-Hauptsturmführer of the 14th Waffen Grenadier Division of the SS (1st Galician) aka SS Galichina, unveiled 2007. SS Galichina was formed as a division in the Waffen-SS in 1943; among the formation’s war crimes is the Huta Pieniacka massacre, when an SS Galichina subunit slaughtered 500–1,200 Polish villagers, including burning people alive.

Above left, Paliiv (holding paper) at an SS ceremony, 1943–1944. This Waffen-SS officer has a plaque and bas-relief in his birthplace of Perevozets’ (unveiled 2001) as well as a plaque and street in Kalush. The JTA reported on death threats to a man who opposed naming the street.

Below left, a march in Stanislaviv (now Ivano-Frankivsk), western Ukraine, October 1941; below right, a march celebrating the 71st anniversary of SS Galichina’s founding, L’viv, western Ukraine, 2014. L’viv’s 2018 march consisted of hundreds giving coordinated Nazi salutes. See JTA report.

Note: the entries below were added during the January/April 2022 project update.

Bystrychi and seven other locales – A memorial plaque to Taras Bulba-Borovets (1908–1973), the collaborator appointed by the Nazis to head the Ukrainian militia in the Sarny district. Bulba-Borovets’ men organized and carried out numerous pogroms, slaughtering the area’s Jews. In addition to the plaque in his native village, Bulba-Borovets has another plaque in Olevsk, a monument in Berezne and streets in Kyiv, Lutsk, Ovruch, Rokytne (Sarny Raion) and Zhytomyr.

After the war, Bulba-Borovets, like many Nazi collaborators, settled in Canada, where he ran a Ukrainian language newspaper. Above left, Bulba-Borovets (center) with staff, 1941. The banner to the right of the swastika flag says “Long live the German Army!” For more on Bulba-Borovets’ glorification, see article by historian Jared McBride, eyewitness testimony of the Holocaust in Olevsk at Yahad-In Unum and survivor testimony at Yad Vashem.

(Note: The Rokytne street was added August 2023; the Kyiv street was added June 2025.)

Volya Yakubova and 17 other locales – A memorial complex and a separate museum to Andriy Melnyk (1890–1964). In 1940, the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN) split into two factions: OUN-M, led by Melnyk and OUN-B, led by Stepan Bandera. Melnyk’s faction was every bit as genocidal as Bandera’s – an OUN-M newspaper gleefully celebrated the liquidation of Kyiv’s Jews at Babi Yar (see Ivan Rohach entry below).

The OUN-M remained allied with the Nazis, same as the OUN-B. Germany’s 1941 invasion of Ukraine was welcomed with banners and proclamations such as “Glory to Hitler! Glory to Melnyk!” (below left). After the war, Melnyk resettled in Luxembourg and was a fixture in Ukrainian diaspora organizations.

He also has a monument (below right) and street in Ivano-Frankivsk as well as streets in Bila Tserkva, Cherkasy, Chortkiv, Drohobych, Dubno (Rivne Oblast), Kolomyia, Konotop, Korosten, Kovel, Kyiv, Lutsk, L’viv, Rivne, Stryzhivka, Sumy, Tatarbunary and Zhmerynka. In 2020, the World Jewish Congress and the Jewish Confederation of Ukraine denounced Kyiv’s attempt to honor Melnyk.

(Note: Melnyk’s street in Kyiv, which was named despite protests from Yad Vashem, was added August 2023; the Bila Tserkva, Cherkasy, Konotop, Korosten, Kovel, Lutsk, Sumy, Tatarbunary and Zhmerynka streets were added June 2025.)

***

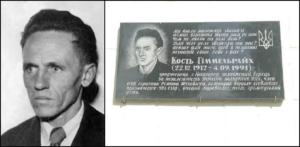

Chernivtsi – A memorial to the Bukovinsky Kuren, a large paramilitary formation comprised of OUN-M members (see Andriy Melnyk entry above). The unit was originally formed in the Ukrainian-Romanian region of Bukovina and headed for Kyiv after the Nazi invasion of Ukraine in 1941. According to several reports, the unit marched into Kyiv around the time of the Babi Yar massacre, when the Nazis, aided by Ukrainian nationalists, gunned down 33,771 Jews in two days in one of the most horrific massacres of the Holocaust.

Afterward, much of the Bukovinsky Kuren was reformed into the 115th and the 118th Schutzmannschaft Battalions. The Schutzmannschaft were auxiliary police battalions composed of local collaborators in the Soviet Union, primarily Ukraine, Belarus and the Baltics. They were under the Ordnungspolizei which was controlled by the SS. These battalions played a crucial role in both the war and the Holocaust: Germany used them to suppress anti-Nazi resistance and carry out the genocide by rounding Jews up in ghettos as well as slaughtering them in nearby fields and forests. Often, the Schutzmannschaft committed war crimes against Jews, other ethnicities such as the Roma and civilians on their own volition, not just under Nazi orders. (For more, see work by Martin Dean.)

Two platoons of the 118th Schutzmannschaft Battalion distinguished themselves by perpetrating the 1943 Khatyn massacre, when they liquidated a Belarusian village by burning the inhabitants alive and gunning down anyone who tried to escape. (See the New York Times on one of the perpetrators who had emigrated to Canada.)

Above left, soldiers of the 115th Schutzmannschaft Battalion, which included Bukovinsky Kuren fighters, march through Kyiv, 1942. See the U.S. section for a memorial to the Bukovinsky Kuren.

Zhyznomyr – This village has a plaque to OUN-M member Oleksa Babiy (1909–1944) who directly participated in the Babi Yar massacre while serving in the Sonderkommando 4a unit of Einsatzgruppe C, the SS death squad that bears primary responsibility for the slaughter. Two years later, Babiy became an officer in SS Galichina, the Ukrainian Waffen-SS division (see Volodymyr Kubiyovych entry below for more on SS Galichina). Above right, Jews forced to undress and give up possessions before being shot in Babi Yar. See Yad Vashem testimonies here.

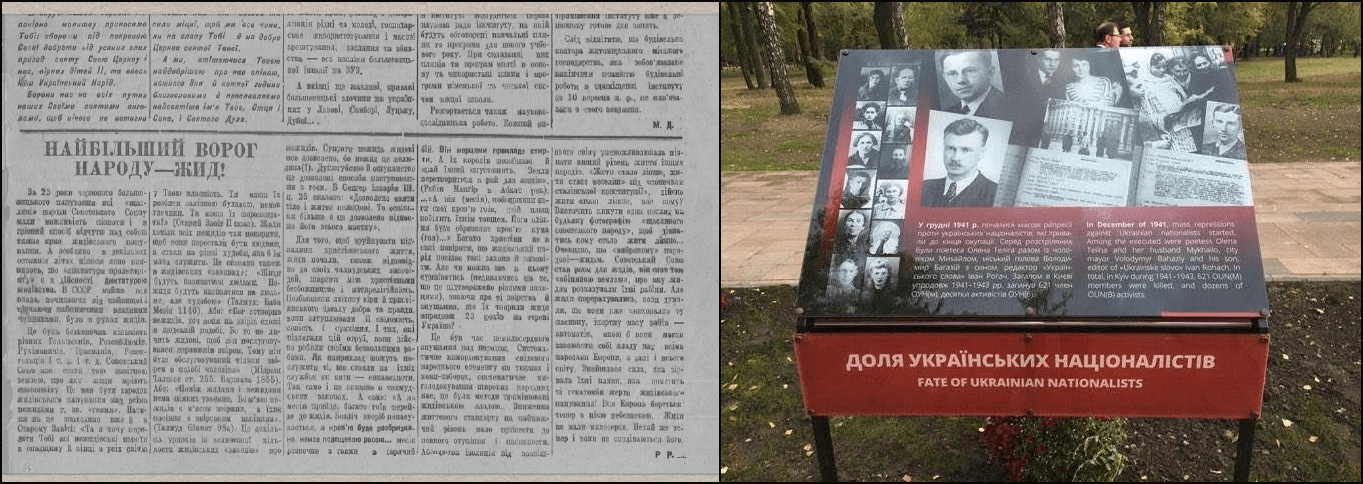

Kyiv and two other locales – A street named for OUN-M member Ivan Rohach (1914–1942). A virulent antisemite, Rohach published and edited the Ukrayins’ke Slovo, an OUN-M newspaper which vociferously advocated for the genocide of Ukraine’s Jews. On October 2, 1941, three days after Germans and Ukrainian collaborators exterminated 33,771 Jews at Babi Yar, Rohach ran an editorial titled “The Jew Is the Greatest Enemy of the People,” calling on Ukrainians to show Jews no mercy (above left).

A week later, he ran an article urging readers to be on the lookout for any Jewish survivors hiding in the city. The same week, the Ukrayins’ke Slovo celebrated the improved life in Kyiv, praising the abundance of “unoccupied” housing which had suddenly become available. (This housing was Jewish homes rendered “unoccupied” by the slaughter of their inhabitants.)

Eventually, the Germans grew tired of some of their OUN-M lackeys and executed Rohach. In 2016, the Ukrainian government made the obscene decision to mourn him as a Nazi victim during commemorations of the Babi Yar massacre – the massacre he had so enthusiastically endorsed (above right).

Rohach has an additional street in Khust and a plaque and street in Velykyi Berezhny.

Kyiv and 35 other locales – A plaque to Oleh Olzhych (1907–1944), archeologist, writer and prominent OUN-M member. Olzhych came to Kyiv part of an OUN-M formation designed to aid the nationalist takeover of Ukraine in 1941. He became a key figure in the Ukrayins’ka Natsional’na Rada. This OUN-M entity coordinated the formation of Ukrainian auxiliary police that aided the Germans. It also published propaganda such as the Ukrayins’ke Slovo (see Ivan Rohach entry above).

Olzhych’s honors include a library and street (with plaque) in Kyiv; a statue, library, street (with plaque) and another plaque in Zhytomyr; plaques and streets in Chernivtsi, Khust, L’viv, Rivne and Tyachiv; streets in Arbuzynka, Bilokorovychi, Ivano-Frankivsk, Korostyshiv, Kovel, Kremenchuk, Kremenets, Kropyvnytskyi, Letychiv, Lutsk, Nadvirna, Novyi Buh, Olevsk, Ostroh, Poltava, Rozsoshentsi, Sambir, Stryi, Sumy, Trubky, Verhnya Yablunka, Volodymyr-Volynskyi, Vyzhnytsya, Zalishchyky, Zdolbuniv, Zhuky and Zolochiv; a street and school in Mykolayiv; and a school in Pushcha-Vodytsia. See the U.S. section for an Olzhych bust.

Perechyn – The town has a street jointly honoring brothers Ivan and Panas Kedyulich. Ivan Kedyulich (1912–1945) was an OUN-M member who came to Kyiv with the same formation as Oleg Olzhych (see entry above). Kedyulich became chief of the city’s local auxiliary police which aided the Nazis with massacres in Babi Yar and elsewhere. Police units organized by Kedyulich also provided fighters for the Schutzmannschaft battalions. Above right, fighters of the 115th Schutzmannschaft in Kyiv, 1942.

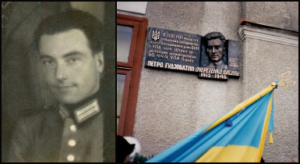

Ivanhorod – A plaque to Kost Himmel’raich (1912–1991), OUN-M member who worked with Ivan Kedyulich (see entry above) to form Kyiv’s German-controlled local auxiliary police. Himmel’raich’s plaque, like many plaques to Ukrainian collaborators, is located on a school where he’s presented as a role model for children.

Silets’ (Chervonohrad Raion) and Sosnivka (Sokal Raion) – The June 1941 German invasion of Ukraine was accompanied by widespread pogroms resulting in the murder of thousands of Jews across western Ukraine. Many were organized and instigated by the OUN-B – the OUN’s Stepan Bandera branch (for more on the OUN split see Andriy Melnyk entry above). This included Ivan Klymiv (1909–1942) aka Klymiv-Lehenda, who was propagating leaflets urging the Ukrainian population to kill Jews.

While the invasion was happening, the OUN-B proclaimed its creation of a Ukrainian government led by Yaroslav Stetsko. This self-declared government formally pledged to work closely with Adolf Hitler (see Stetsko entry for more). Klymiv became minister of political coordination. In addition to the monument, he has a street and school in Silets’ and a joint monument to him and Bandera in Sosnivka (Sokal Raion).

Konyukhiv and five other locales – Konyukhiv has a monument, museum and street to village native Oleksandr Hasyn (1907–1949), deputy minister of defense in the 1941 self-declared OUN-B government. Afterward, Hasyn worked closely with fellow collaborator and UPA commander Roman Shukhevych when the UPA was conducting the ethnic cleansing of Poles (see Vasyl Vasylyashko entry below). Hasyn also has a plaque in Volya-Zaderevatska and streets in Molodynche, Sambir, Skole and Stryi.

(Note: The Molodynche street was added June 2025.)

Zolota Sloboda – A bust of Yaroslav-Mykhailo Starukh (1910–1947), secretary of the ministry of information and propaganda in the self-declared OUN-B government. The village also has a plaque of Starukh on a school building, where he’s promoted as an example to children.

L’viv and Zmiivka – A plaque commemorating the proclamation of the self-declared OUN-B government in L’viv’s main square. This is particularly obscene given that as the proclamation was announced, the OUN-B was instigating and carrying out pogroms that made L’viv’s streets run with the blood of 6,000 Jews (above left). The Memorial to Fighters for Ukraine’s Freedom in Zmiivka also includes a commemorative plaque for the 1941 proclamation. See the U.S. section for another plaque commemorating the OUN-B proclamation.

L’viv – Above left, L’viv’s mayor Yurii Polianskyi (1892–1975) welcomes Governor-General of Poland Hans Frank to the city, August 1, 1941. By this point, at least 6,000 of L’viv’s Jews were butchered in a series of pogroms incited and carried out in large part by Ukrainian nationalists.

Frank, aided by Ukrainian collaborators, went on to oversee the genocide of over 200,000 L’viv Jews; in 1946 he was hanged for crimes against humanity by the Nuremberg Tribunal. Polianskyi, on the other hand, emigrated to Argentina where he became a university professor. His memorial plaque in L’viv, above right, lists his academic achievements while omitting his WWII collaboration. See L’viv massacre and ghetto survivor testimonies, Yad Vashem.

Bodnariv and L’viv – Bodnariv’s monument to Oleksandr Lutskyi (1910–1946), an officer in Nazi Germany’s Nachtigall auxiliary battalion which invaded Ukraine alongside other Third Reich forces in June 1941. Nachtigall was a battalion in the Abwehr, the military intelligence division of the Third Reich’s armed forces. It was composed of Ukrainian volunteers, primarily from the OUN-B branch of the OUN. The Ukrainian commander was Roman Shukhevych who is glorified across Ukraine today (see his entry earlier).

In the fall of 1941, Nachtigall was reorganized into the 201st Schutzmannschaft auxiliary police battalion, which was involved in lethal antisemitic violence and brutal suppression of anti-Nazi resistance in Belarus. See the Bukovinsky Kuren entry for more on the Schutzmannschaft. Lutskyi also has a street in L’viv.

Zavyshen’ – In 2018, this village unveiled a plaque to Vasyl Vasylyashko (1918–1946) who served in the Nachtigall Battalion, then in the 201st Schutzmannschaft Battalion. Afterward, Vasylyashko became a commander in the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA), the OUN-B’s paramilitary wing created in 1943 and responsible for the ethnic cleansing of 70,000–100,000 Polish villages in the Volyn region.

There’s no clear historical photo of Vasylyashko; his plaque can be seen in a video of its unveiling ceremony. Above left, Nachtigall marching through L’viv on June 30, 1941, right as anti-Jewish pogroms raged throughout the city. Above right, the 201st Schutzmannschaft in training, 1942; Roman Shukhevych is in the front row, closest to the camera.

Ternopil – A plaque and street honoring Omelyan Polovyi (1913–1999). Polovyi followed the familiar path of OUN-B members, serving in Nachtigall, then commanding a platoon in the 201st Schutzmannschaft Battalion and later becoming a UPA colonel. Polovyi and other OUN-B fighters from Nachtigall, Schutzmannschaft and local auxiliary police battalions gained hands-on experience carrying out the Holocaust in 1941 and 1942. This murderous experience was put to use in 1943, when they joined the UPA and organized the ethnic cleansing of Poles.

Volodymyrtsi – A plaque to Petro Hudzovatyi (1912–1946), who fought in Nachtigall, then the 201st Schutzmannschaft Battalion then the UPA, where he commanded a district unit. The plaque is erected on a government building where Hudzovatyi once worked.

Spasiv and Stryi – Spasiv’s bust of Vasyl Sydor (1910–1949), Nachtigall officer who became oberzugführer in the 201st Schutzmannschaft Battalion. Afterward, Sydor played a crucial role in the formation of the UPA, eventually becoming commander of UPA-West (one of the paramilitary’s four subdivisions). He also has a middle school in Spasiv and a street in Stryi. In 2020, the World Jewish Congress and the Jewish Confederation of Ukraine denounced Kyiv’s attempt to honor Sydor.

Lypivka (Rohatyn Raion) – A monument to Oleksii Demskyi (1922–1955), another member of Nachtigall and the 201st Schutzmannschaft Battalion. Above left, the 201st Schutmannschaft in training with Roman Shukhevych in the front row, second from left.

Sprynya – This village’s joint monument to several OUN figures includes a statue of Ivan Hrynokh (1907–1994). Hrynokh, a priest in the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church, served as chaplain in the Nachtigall Battalion, where he was awarded the Iron Cross, a Nazi Germany military honor. After his service to the Third Reich, Hrynokh became a publisher and professor in Munich. Hrynokh, like many OUN leaders, enjoyed a fruitful relationship with the CIA for decades after WWII: the agency’s analysis of him notes “he is very severe…he is capable of great cruelty.” See FOIA research and the CIA reading room for declassified documents.

Khryplyn – This village celebrates two homegrown collaborators with a bust of Dmytro Hakh (1919–1945), above left, and a plaque to Stepan Burdyn (1912–1947), above right. Both served in Nachtigall (Hakh was an officer), then the 201st Schutzmannschaft Battalion. Afterward, both became UPA commanders.

Sambir and Storona – Sambir’s bust to Terentii Pikhotskyi (1912–1944) who fought in Nachtigall before becoming a UPA commander. He also has a plaque on a school in his home village of Storona.

Sadzhava – This village honors native son Oleksiy Khymynets (1912–1945) with a monument and street. Khymynets served Germany not just in Nachtigall and the 201st Schutzmannschaft Battalion but also in local auxiliary police (see Volodymyr Schygel’skiy entry below for more on role of police). Afterward, he became a UPA officer. His street uses his nom de guerre “Blahyi”. Above right, a chilling rare photo of the Holocaust by bullets as it happened; Ukrainian police execute a woman and two children in Miropol, 1941.

Nazavyziv – A memorial plaque honoring Danylo Rudak (1917–1948), who served in Nachtigall and the 201st Schutzmannschaft Battalion, then became a UPA officer.

Chortkiv – A bust of Petro Khamchuk (1919–1947), another member of one of Nazi Germany’s Schutzmannschaft battalions. Afterwards, Khamchuck became a UPA commander.

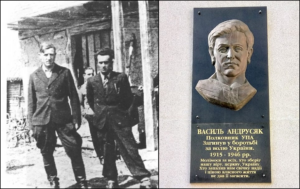

Ivano-Frankivsk and three other locales – On the outside of the city’s Cathedral of the Transformation is a plaque to Vasyl Andrusyak (1915–1946). In 1941, Andrusyak was platoon commander in Nazi Germany’s Roland Battalion. Roland was a companion formation to the Nachtigall Battalion (see entries above): just like Nachtigall, it was a Ukrainian auxiliary unit in the Abwehr (Third Reich military intelligence) that participated in the Nazi invasion of Ukraine and was later reorganized into the 201st Schutzmannschaft Battalion.

After serving in Roland, Andrusyak became a UPA officer. He also has a statue, street and museum in his hometown of Sniatyn and streets in Hrabivka (Ivano-Frankivsk Oblast) and Kalush.

Tuchyn – This village honors native son Stepan Trokhymchuk (1909–1945) with a street. This is particularly perverse, considering that in 1942 Trokhymchuk was deputy chief of Tuchyn’s local auxiliary police which aided the Nazis in liquidating the Tuchyn ghetto and exterminating its 4,000-plus Jews. Before the war, Tuchyn’s population was majority Jewish; around 20 Jews survived the Holocaust enabled by Trokhymchuk (see survivor testimony here; survivor interviews by Yad Vashem; and eyewitness testimony by Yahad-In Unum). Prior to assisting the Nazis in Tuchyn, Trokhymchuk served them in the Roland Battalion. Above left, Trokhymchuk (on right); above right, Roland Battalion training in Seibergsdorf Austria, 1941.

Kaminne – A memorial plaque to Petro Melnyk (1910–1953), who served in Roland, then the 201st Schutzmannschaft Battalion and then became a UPA commander. The plaque omits any mention of his service for the Nazis.

Ivano-Frankivsk and Petryliv – Ivano-Frankivsk features a plaque to Mykola Tverdohlib (1911–1954), who served in Roland prior to becoming a UPA commander. He also has a memorial in his birth village of Petryliv.

Rai – Dmytro Myron (1911–1942) aka Orlyk was one of the OUN’s main ideologues who authored the “44 Rules of the Life of a Ukrainian Nationalist,” a set of tenets considered foundational to the OUN.

Myron was the political educator of the Roland Battalion. His writings are filled with antisemitic imagery depicting Jews and other ethnicities as a “foreign element” syphoning resources and feeding off of Ukraine; he also portrayed Jews as agents of Communism (an old antisemitic trope propagated by Josef Goebbels, among others). His bust is in his home village of Rai.

L’viv and Brovary – Both have streets named for Roman Sushko (1894–1944), OUN leader who commanded the Bergbauernhilfe aka the Ukrainian Military Units of Nationalists or the Sushko Legion. The Sushko Legion was another Ukrainian volunteer unit composed mostly of OUN members in Nazi Germany’s armed forces.

The Sushko Legion entered WWII earlier than the Nachtigall and Roland battalions (see entries above). Nachtigall and Roland were used by the Nazis in the 1941 invasion of the Soviet Union; the Sushko Legion was designed to aid the Third Reich’s 1939 invasion of Poland. Above right, the legion’s badge.

L’viv – One of the fighters in the Sushko Legion (see entry above) was Volodymyr Schygel’skiy (1921–1949). Afterward, Schygel’skiy served in several Nazi-controlled local auxiliary police units that actively partook in the Holocaust in western Ukraine. He later became a UPA officer. The plaque describing this war criminal as a “legendary commander” is on a building where he attended school.

Unlike the Schutzmannschaft battalions (see entries above), which were deployed by the Third Reich to various locations, local auxiliary police units such as those Schygel’skiy served in were based in specific cities, towns and villages throughout Ukraine. These local collaborators were invaluable to the Nazis: they spoke the local languages, knew the people and were intimately familiar with the terrain, including where Jews or anti-Nazi resistance fighters could hide.

Auxiliary police participated in the Holocaust by rounding up Jews, hunting down escapees, imprisoning Jews in ghettos, forcibly relocating them to be exterminated in death camps or simply massacring them on the spot, on the outskirts of towns or in pits dug in local forests. The security and guard duties performed by local auxiliary police freed up SS Einsatzgruppen death squads and Schutzmannschaft battalions, which were then deployed to perpetuate the Holocaust in other regions.

During the rare cases Nazi collaborators have been deported from the U.S., Washington treated service in the local auxiliary police as equivalent to serving the Nazis. For a graphic eyewitness account of the crucial role of local auxiliary police in the Holocaust in Ukraine, see testimony of Hermann Friedrich Gräbe from the Nuremberg trials and survivor testimony from Yad Vashem. Also see historian Wendy Lower’s haunting book “The Ravine”.

Tashan’ – This memorial to “Fighters for Ukrainian Freedom” features a plaque to Petro Samutin (1896–1982), an officer in the Abwehr, the Third Reich’s military intelligence division. After the war, Samutin relocated to the U.S.

Melnyky (Cherkasy Raion, Medvedivka Hromada) and 12 other locales – A monument to Yurii Horlis-Horskyi (1898 – disappeared 1946). A hero of Ukraine’s WWI-era independence struggles as well as a writer, Horlis-Horskyi spent WWII working as an agent of the Abwehr, helping the Nazis uncover resistance efforts in Ukraine. Horlis-Horskyi mysteriously vanished in 1946. He has another monument in Rozumivka (Kirovohrad Oblast) and streets in Dnipro, Holovkivka (Cherkasy Oblast), Kam’yanka, Kremenchuk, Kropyvnytskyi, L’viv, Poltava, Reshetylivka, Rivne, Smila and Zvenyhorodka.

(Note: The Dnipro, Holovkivka (Cherkasy Oblast), Kam’yanka, Kremenchuk, Kropyvnytskyi, Reshetylivka and Smila streets were added June 2025.)

Lityn (Vinnytsia Oblast) and two other locales – Lityn’s memorial plaque and street for Omelyan Hrabets (1911–1944) celebrate another OUN member who served in the Nazi-controlled local auxiliary police. Hrabets’ service was in Rivne (then called Rovno), where the Germans, together with local police units, murdered over 20,000 Jews by deporting them from the city’s ghetto to death camps or shooting them on site (see here for survivor testimony; eyewitness testimony by Yahad-In Unum). Above left, Hrabets in uniform, on left; note the police armbands. Hrabets then became a colonel in charge of the UPA-South division. He also has streets in Ladyzhyn and Vinnytsia.

(Note: The Ladyzhyn street was added March 2024.)

Zhytomyr and two other locales – A street named for Leonid Stupnytskyi (1891–1944) who led the OUN-B’s 1st Ukrainian Regiment “Holodny Yar,” an auxiliary police training battalion in Rivne in 1941. Shortly afterward, his unit was reformed into a police training regiment under control of the German army. See Omelyan Hrabets entry above for more on the Holocaust in Rivne. Stupnytskyi also has streets in Rudnya and Ostroh. Above right, Jews in Storow forced to dig their own graves before being massacred, July 1941. Such haunting scenes were commonplace in WWII Ukraine.

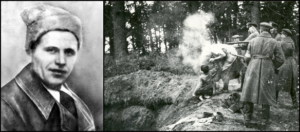

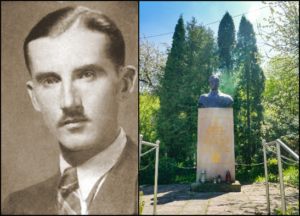

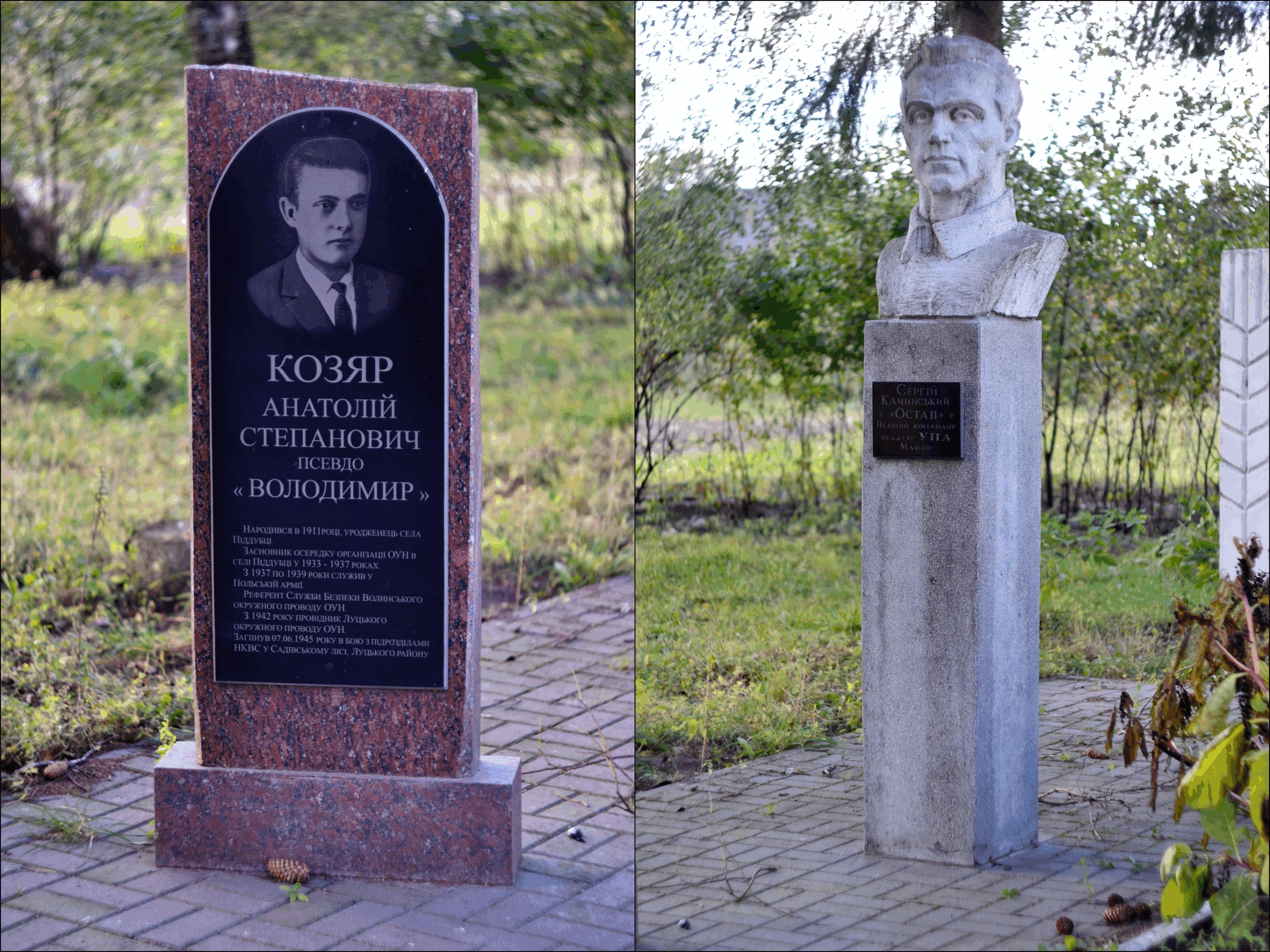

Piddubtsi (Volyn oblast) and Lutsk – The village’s Alley of Glory contains monuments to Serhii Kachinskyi (1917–1943), below right, and Mykola Yakymchuk (1914–1947), above right. Kachinskyi was commander of the Holodny Yar battalion (see entry above). Yakymchuck is another OUN member intimately involved in mass murders of both Jews and Poles. He served the Nazis as head of local auxiliary police of the city of Lutsk, which hunted down Jews. Later, Yakymchuk became a UPA commander in Volyn which perpetrated the ethnic cleansing of Poles. The Alley of Glory also contains a monument to native-born OUN commander Anatoliy Koziar (1913 – 1945), below left; Koziar also has a street in Lutsk. See testimony of a survivor of Lutsk Ghetto liquidation, in which Ukrainian police played a key role (in Hebrew with English subtitles).

(Note: Koziar’s monument and street were added March 2024.)

***

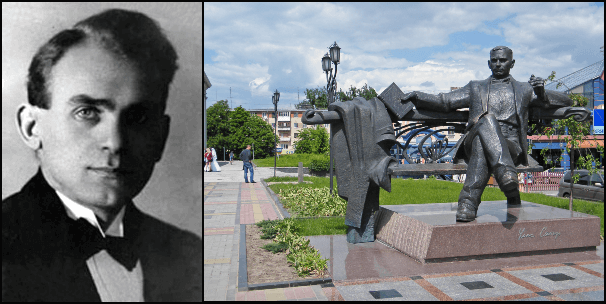

Rivne and 24 other locales – Rivne has a statue (above right), museum, street and memorial plaque to Ulas Samchuk (1905–1987). The virulently antisemitic writer and OUN member published Rivne’s Volyn newspaper which ran hundreds of articles fomenting antisemitism. The paper’s fawning front page lead section, titled From the Führer’s Headquarters, covered Hitler’s decisions and ran excepts from his speeches. “Today is a great day for Kyiv,” Volyn wrote on the eve of the Babi Yar massacre. “The German authorities met the passionate desires of Ukrainians, ordering all Jews, of which there are still 150,000 remaining, to leave Kyiv.”

After the war, Samchuk settled in Canada where he founded a Ukrainian writers association. Samchuk’s whitewashers extol him as a writer while saying nothing about his antisemitism and Nazi propaganda. This tactic is used with other collaborationist authors like Hungary’s Albert Wass and Jòzsef Nyírő (see the Hungary and Romania sections).

Samchuk has a statue, museum and memorial plaque in Tyliavka; a museum and memorial plaque in Derman’; a plaque in Horodok; a bust and street in Zdolbuniv; and streets in Bila Tserkva, Dubno, Kalush, Kaniv, Kostopil, Kovel, Kremenets, Kyiv, Lukiv, Lutsk, L’viv, Lyuboml’, Novovolynsk, Ostroh, Rokytne (Sarny Raion), Stepan’, Ternopil, Volodymyr-Volynskyi, Zbarazh (Ternopil Raion) and Zhytomyr. In 2020, the World Jewish Congress and the Jewish Confederation of Ukraine denounced Kyiv’s attempt to honor Samchuk.

(Note: The Derman’ museum and Kyiv and Rokytne streets were added August 2023; the Kaniv street was added March 2024.)

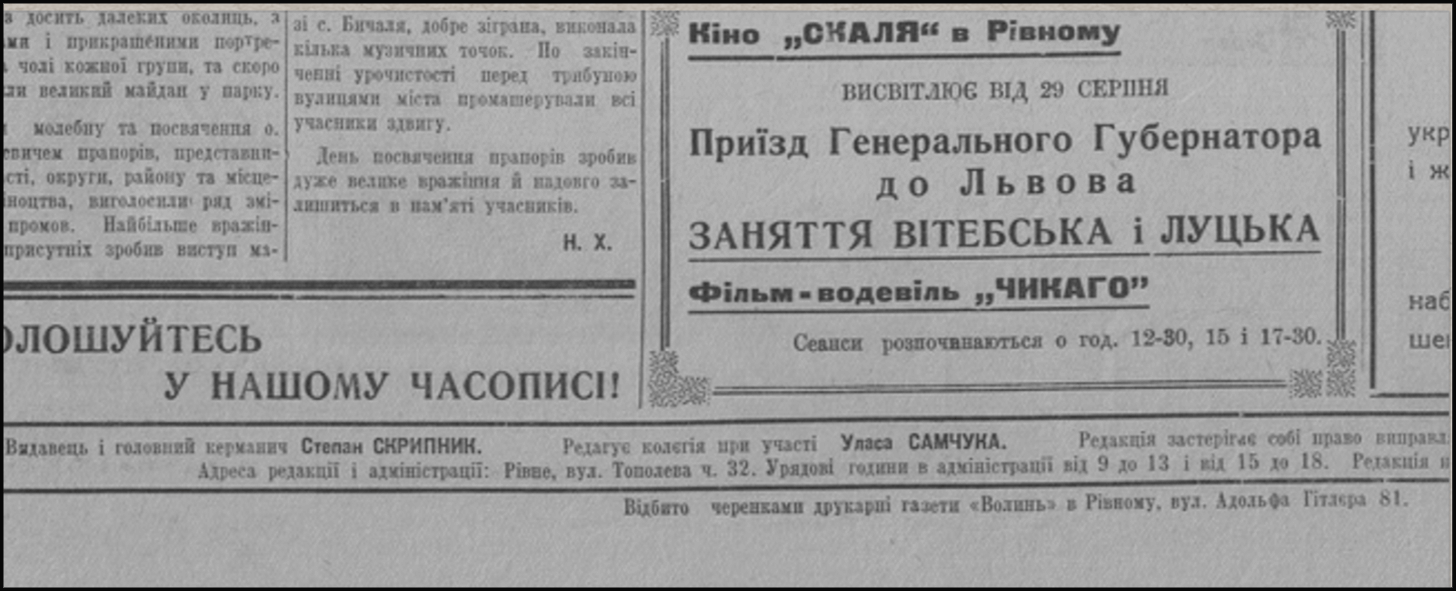

Kyiv and 10 other locales – A memorial plaque to Stepan Skrypnyk (1898–1993) who became Patriarch Mstyslav, head of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church. In 1941–1942, around the time Skrypnyk was ordained into the priesthood, he was the publisher and manager of the extraordinarily antisemitic paper Volyn (see Ulas Samchuk entry above).

On March 29, 1942 Skrypnyk wrote a paean to the “Great European named Adolf Hitler,” who was “sent by providence” to liberate Europe and the world from Jews and Bolsheviks. Skrypnyk waxed poetic about Ukraine’s deliverance from “Moscow-Jewish Asiatic bondage,” eagerly anticipating the day “the fanfares of the German army will carry the song of victory across the globe.”

Skrypnyk’s Volyn incited genocidal hatred as the Holocaust raged across Ukraine. On November 6, 1941, Germans and Ukrainian collaborators exterminated about 21,000 Jews in Rivne. Three days later, Volyn – a Rivne-based paper – celebrated by running antisemitic cartoons with a caption: “For the Judeo-Bolshevik hydra, it’s the final hour.”

Ukraine’s honors to Skrypnyk include another plaque and a street in Kyiv; a plaque and street in Ternopil; a museum (with plaque) and street in Poltava; two plaques in Ivano-Frankivsk, two in L’viv, one in Kosiv and another in Zalishchyky; and streets in Borsuky, Kamyanets-Podilskyi, Pidvolochysk and Verkhovyna.

Below, the masthead from Volyn’s inaugural edition, September 1, 1941. It lists Skrypnyk as publisher and manager, Ulas Samchuk as editor and the printing press’ address as 81 Adolf Hitler Street. See the U.S. section for an honorary street designation for Skrypnyk.

***

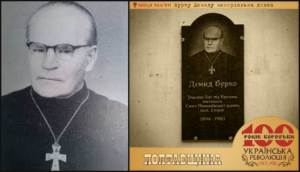

Poltava – A plaque commemorating Demid Burko (1894–1988), clergyman and writer who published screeds about the “battle of civilized nations against global Judeo-Bolshevism,” and claimed Stalin starved Ukraine “to build a Jewish kingdom.” The vile lie of Jews being responsible for Ukraine’s 1932–1933 famine was – and continues to be – used as “justification” for Ukrainians butchering Jews during the Holocaust.

Burko, just like Stepan Skrypnyk (see above), encouraged Ukrainians to join Hitler’s crusade against “Judeo-Bolshevism”. His exhortations were published in Poltava’s Holos Poltavshyny paper while the Holocaust unfolded; 5,000 of the city’s Jews were murdered. After successfully helping instigate the Holocaust in Poltava, Burko escaped to Germany, where he spent decades playing a leadership role in the Ukrainian Orthodox Church while publishing his works.

Romny and Poltava – Both places have streets named for Leonid Parhomovych (1921–1990) aka Poltava. An antisemitic poet, Poltava celebrated the destruction of Romny’s Jews and churned out tracts like his ode to Hitler’s 53rd birthday. “The day rings out, the boundless sky is blue/It’s no coincidence that on this day, was born the Great Führer,” warbled Poltava, evoking images of Hitler as a deity of spring and rebirth.

While Poltava was publishing this, Romny’s Jews were being liquidated with the participation of Ukrainian police. After the war, Poltava ended up in the West working for the U.S.-government’s Radio Free Europe and Voice of America. He also has a plaque in Romny, above right.

Drohobych and Biynychi – A plaque to OUN members Andriy Shukatka (1918–1943), Volodymyr Kobilnyk (1904–1945) and Vasyl Nykolyak (1912–1944) on the library of Drohobych State Pedagogical University; in 1941, the building housed the city’s OUN headquarters. The Holocaust in Drohobych happened the same way as in other towns and villages in Ukraine: OUN members helped form a local auxiliary police which worked under the Nazis to imprison the city’s Jews in a ghetto. Afterward, the majority of Drohobych’s Jews were exterminated by being deported to the Belzec death camp or gunned down in the streets and nearby forest.

Shukatka (above left), Kobilnyk and Nykoyak were OUN leaders in Drohobych while the genocide was unfolding. Nykolyak, who went on to become a UPA officer, also has a street and memorial plaque in his home village of Biynychi. See Yahad-In Unum survivor interview here.

Halych and Ivano-Frankivsk – The town of Halych features a bas-relief of Volodymyr Chav’yak (1922–1991), an officer in the local auxiliary police that aided Germany in annihilating thousands of Jews in Stanislaviv (now Ivano-Frankivsk). Local police were deployed to hunt Jews down, march victims to mass murder sites, execute them and guard Stanislaviv’s ghetto. See accounts in the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, Yad Vashem (survivor documentary; more testimony) and Yahad-In Unum.

Afterward, Chav’yak went on to command a UPA battalion. Perversely, he also has a street and plaque in Ivano-Frankivsk, the city whose Jews he helped eradicate.

Lyuboml’ – The monument to freedom fighters includes a memorial plaque for Serhii Bohdan (1921–1950) who commanded the local auxiliary police. The Jews of Lyuboml’ were wiped out; out of 4,500, only 51 survived. The shooting was done by Einsatzgruppen working together with Lyuboml’s’ police. See coverage in the New York Times, Yad Vashem (survivor testimony) and a Lyuboml’ memorial book.

Hrabovets (Ivano-Frankivsk Oblast) – A monument at the house of Kostiantyn Peter (1893–1953) who served Nazi Germany as chief of the local auxiliary police of Bohoradchany and then in Tysmenytsia. During his service, the local auxiliary police helped annihilate the Jewish population. Peter then became a reconnaissance chief in the UPA. See Yahad-In Unum eyewitness testimony here.

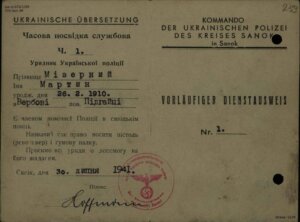

Verbiv (Pidhaitsi Hromada) – A monument to Martin Mizernyi (1910–1949), regional commander of local auxiliary police in the town of Sanok in Nazi-occupied Poland. Sanok’s ghetto eventually grew to imprison 10,000–13,000 Jews who were deported to extermination camps. Mizernyi later joined the UPA, where he served as district commander. Below, Mizernyi’s Third Reich police identification allowing him to carry a handgun and baton and granting him police power.

***

Rohatyn and two other towns – A plaque to Vasyl Ivakhiv (1908–1943), commander of local auxiliary police in Peremyshliany; the police burned down the town’s synagogue including the Jews inside. Afterward, Ivakhiv became a UPA commander in Volyn, where it committed ethnic cleansing of Poles. He also has a monument and plaque in Podusil’na and a street in Bukovyna. See testimony of a survivor of Peremyshliany Ghetto, Yad Vashem.

(Note: The Bukovyna street was added June 2025.)

Yabluniv (Kosiv Raion) – Yurii Dolishnyak (1916–1948) was an officer in the Nazi-controlled local auxiliary police in the village of Kosmach who later became a UPA commander. Yabluniv also gave Dolishnyak a street which uses his nom de guerre “Bilyi”.

Zarichchya (Nadvirna Raion) – A monument and street to Pavlo Vatsyk (1917–1946) in his home village; Vatsyk served in the Nazi-controlled local auxiliary police in his home region. Afterward, he became a UPA commander.

Stopchativ – A monument to Vasyl Skryhunets (1893–1948) who served in the local auxiliary police before becoming a UPA commander. His monument uses his nom de guerre “Hamaliya”.

Lutsk and Kovel – Both locales have streets named for Oleksa Shum (1919–1944), member of the local auxiliary police that aided the Nazis in slaughtering about 18,000 Jews in the city of Kovel. Jews made up half of Kovel’s pre-war population; the community was virtually exterminated. Above right, Ukrainian police (with white armbands) preparing to execute Jews in Chernihiv, 1941.

Truskavets – A monument and street named for Roman Ryznyak (1921–1948), who served in Truskavets’ local auxiliary police. Ryznyak went on to become a regional commander in the Sluzhba Bezpeky – the OUN-B’s counterintelligence apparatus which spearheaded the ethnic cleansing of Poles in Volyn. See information on the Holocaust in Truskavets here.

Nyzhniy Bereziv and five other locales – A monument to Mykola Arsenych (1910–1947), who headed the OUN-B’s Sluzhba Bezpeky. He also has a bas-relief in Nyzhniy Bereziv and streets in Dnipro, Kolomyia, L’viv, Sokal and Zviahel.

(Note: The Dnipro, L’viv and Sokal streets were added June 2025.)

Petranka and Dev’yatnyky – A plaque to Yaroslav Dyakon (1913–1948), who headed the Sluzhba Bezpeky in 1947–1948 after Mykola Arsenych (see entry above) was killed. Prior to that, Dyakon was head of the local auxiliary police in the town of Bibrka. In 1942, most Jews from the Bibrka ghetto were deported to the Belzec death camp; in 1943, local auxiliary police helped the Germans burn Bibrka’s remaining Jews alive. Dyakon also has a school in Dev’yatnyky. See Yahad In-Unum eyewitness testimony of the Holocaust in Bibrka.

Ivano-Frankivsk and six other locales – Ivano-Frankivsk has a bas-relief (above right), monument and street to Stepan Lenkavskyi (1904–1977), one of the main OUN ideologues who led the OUN-B after Stepan Bandera was assassinated in 1959. Lenkavskyi authored The Decalogue of a Ukrainian Nationalist, a set of tenets considered foundational to the organization. He was also a murderous antisemite: “We will adopt any methods that lead to their destruction,” Lenkavskyi exhorted at an OUN-B council which was discussing the fate of Jews.

Lenkavskyi who, like many in the OUN-B leadership, had successfully emigrated to the West, also has a monument in Uhornyky; a plaque in Fit’kiv and another on a joint monument to him and other OUN leaders in Morshyn; and streets in Bryukhovychi, Lutsk, Stryi, Yasenytsya-Sil’na and Zahvizdya.

(Note: The Lutsk street was added March 2024; the Bryukhovychi and Yasenytsya-Sil’na streets were added June 2025.)

L’viv and two other locales – Volodymyr Kubiyovych (1900–1985) was a Ukrainian leader who closely worked with Hans Frank, the Governor-General of Poland responsible for orchestrating the Holocaust in western Ukraine. Above left, Kubiyovych (second from left) attends a function with Frank. Kubiyovych leveraged his relationship with the Third Reich to convince the Nazis to create a Ukrainian unit in Waffen-SS, the military arm of the Nazi Party responsible for the Holocaust. His persistent lobbying was instrumental in the formation of the 14th Waffen Grenadier Division of the SS (1st Galician) aka SS Galichina in 1943. It went on to commit war crimes such as the 1944 Huta Pieniacka massacre, when its fighters burned 500–1,000 Polish villagers alive.

Kubiyovych’s genocidal activities include chairing L’viv’s Ukrainian Central Committee, a collaborationist organization recognized by the Third Reich. In addition to helping organize and recruit local auxiliary police, the committee warned Ukrainians that anyone helping Jews hide would be severely prosecuted (below left). Thanks to such efforts, L’viv’s thriving Jewish community, which had comprised a third of L’viv prewar population, was wiped out; out of 200,000, less than 800 survived (which makes for a 0.4% survival rate).

While Hans Frank was hanged for crimes against humanity in Nuremberg, Kubiyovych moved to the West where he was celebrated as a geographer and activist. He even edited a book about the SS division he helped create. In addition to his plaque and street in L’viv, Kubiyovych has streets in Ivano-Frankivsk and Kolomyia. Below right, Kubiyovych (circled) gives the Nazi salute at a 1943 rally. In 2020, the World Jewish Congress and the Jewish Confederation of Ukraine denounced Kyiv’s attempt to honor Kubiyovych.

***

L’viv and Sokal – Both have streets named for Viktor Kurmanovych (1876–1945), one of the founders of SS Galichina. Above right, festivities in L’viv in honor of SS Galichina, 1943. Note the SS bolts, swastikas and SS Galichina lion and crowns placards.

Rohatyn – A street and museum for Mykola Uhryn-Bezhrishny (1883–1960), who advocated for SS Galichina’s creation and served in the division under the rank of Waffen-Obersturmführer.

Prior to joining SS Galichina, Uhryn-Bezhrishny published the Rohatyn’ske Slovo newspaper which praised the Nazi invasion of Ukraine, ran paeans to “Adolf Hitler and his fearless knights,” and blamed Ukraine’s problems on “Judeo-Communists.” It also recruited Ukrainians for the German-controlled local auxiliary police which helped eradicate Rohatyn’s Jewish community.

Above right, Rohatyn’ske Slovo article from November 1941 celebrates the annihilation of Ukraine’s Jews: “the cities still have a certain percentage of Jews, albeit much diminished…Jews in the villages have been liquidated, one way or another….in some villages this took on a festive mood – for example, Jews were forced to march with signs saying ‘We are your tormentors’.”

The Uhryn-Bezhrishny museum is part of the Rohatyn Museum Complex which includes the nearby Church of the Holy Spirit, a medieval wooden church. In 2013, the church was designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. It’s important to note that UNESCO lists only the church and not the museum as part of the heritage site; however the formal link between a UNESCO-designated site and a “museum” glorifying a Waffen-SS officer can be easily used to whitewash Uhryn-Bezhrishny.

Kyiv and six other locales – A major street in Ukraine’s capital named for Mykhailo Omelyanovych-Pavlenko (1878–1952). Omelyanovych-Pavlenko was a hero of Ukrainian liberation movements of the WWI era. By the time WWII came around, he was recruiting soldiers for the Third Reich via the Ukrainian Liberation Army, an umbrella organization which funneled Ukrainian volunteers to various Nazi military formations.

Omelyanovych-Pavlenko was overjoyed to learn of Hitler greenlighting SS Galichina’s creation – “Hail Hitler! Hail the Ukrainian Army!” he wrote in a letter celebrating the news (above left). He also has streets in Dnipro, Kropyvnytskyi, Kryvyi Rih, Odesa, Pervomaisk (Mykolayiv Oblast) and Voznesensk. Below, Omelyanovych-Pavlenko (sitting) with SS Galichina officers, 1943.

(Note: The Kropyvnytskyi, Kryvyi Rih and Odesa streets were added June 2025.)

***

Ternopil and 24 other locales – The Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church played an important role in SS Galichina’s creation. Bishop Iosif Slipyi (1892–1984) was the Church’s point man. He celebrated mass at SS Galichina’s founding and even furnished the division with priests who served as chaplains. Prior to that, Slipyi served as first deputy in the 1941 self-declared OUN government which had pledged allegiance to Hitler (see Yaroslav Stetsko entry for more).

According to Slipyi’s own memoirs, by 1943 he was well aware of the fate Germany had for the Jews; he still helped provide the Third Reich with SS recruits.

In 1983, forty years later, Slipyi remained proud of SS Galichina. By then, Slipyi, who had spent years in Soviet labor camps, was in Rome. He commemorated the anniversary of SS Galichina’s founding with praise.

“Let the memory of Ukrainian Galichian Division live with us forever as a testament to nations that we strive for freedom, statehood and are prepared for the greatest sacrifices for truth, fairness and peace to be in our land,” he proclaimed, calling on the faithful to pray for SS men.

Slipyi has a statue, seminary, school, street and two plaques in Ternopil; a museum, memorial plaque, bust, school and street in Zazdrist’; a street, museum, center at the Ukrainian Catholic University and massive bas-relief in L’viv; a plaque in Kharkiv; a statue in Truskavets; streets in Bila, Borschiv, Boryatyn, Chervonohrad, Chortkiv, Drohobych, Hrabovets (L’viv Oblast), Ivano-Frankivsk, Kalush, Kolomyia, Mykulyntsi, Radekhiv, Rivne (Mykolayiv Oblast), Rozvadiv, Rudne, Snihurivka, Zady, Zalishchyky and Zhovkva; and a square in Stryi.

Below left, Slipyi (third from right) welcomes Hans Frank to L’viv, August 1, 1941. Four years later, Frank would be hanged for crimes against humanity in Nuremberg. Below right, Ukrainian Greek Catholic bishop Josaphat Kotsylovsky celebrating mass at an SS Galichina ceremony in Przemyśl, summer 1943; note the division’s lion and crowns insignia. See the Canada, Italy and U.S. sections for more Slipyi glorification.

(Note: The Boryatyn street was added June 2025.)

***

Lokhvytsia and three other locales – Lokhvytsia’s plaque celebrating Averkiy Honcharenko (1890–1980) refers to him as a battalion commander in the 1st Division of the UNA aka SS Galichina. SS Galichina was renamed the 1st Division of the Ukrainian National Army (UNA) toward the very end of WWII. Using the innocuous-sounding “1st Division of the UNA” instead of SS Galichina is a tactic that allows whitewashers to publicly honor SS Galichina soldiers without the attention-grabbing “SS”. It’s common both in Ukraine and in the West (see the Austria, Australia and Canada sections).

After his service to Nazi Germany, Honcharenko, who rose to the rank of Waffen-Hauptsturmführer in the Waffen-SS, emigrated to America. This SS officer has additional plaques in Tulchyn and Varva and a street in Brovary. See coverage of Ukrainian Waffen-SS veterans being resettled into the U.K. and Canada in the Guardian, Daily Mail, the National Post and the Jewish News of Northern California.

Lanchyn – This town’s plaque honoring Vasyl Kosiuk (1921–1984) calls him a veteran of the 1st Division of the UNA (see above). After the war, Kosiuk took the traditional Nazi path, ending up in Argentina. Above right, Heinrich Himmler inspecting SS Galichina, May 6, 1944, Neuhammer (now Świętoszów), Poland.

Ivano-Frankivsk – In 2013, Ivano-Frankivsk inaugurated the “Ivano-Frankivsk – A Place of Heroes” program which unveiled memorial plaques throughout the city and environs. These “heroes” include Volodymyr Malkosh (1924–2009), Waffen-Unterscharführer in SS Galichina. In a 2010 interview about his SS service, Malkosh claimed he fought “not for Hitler but against Stalin,” a common whitewashing lie designed to deny fighting in the Waffen-SS.

In the same interview, Malkosh reminisced about how under Nazi rule, with the Jews (whom he called “capitalists” and “merchants”) exterminated, ethnic Ukrainians received more rights. As an example, he mentioned that under the Nazis, L’viv’s higher education schools became composed of 90% ethnic Ukrainians. Malkosh didn’t explain the reason for the sudden demographic change: the schools’ Jewish students had been liquidated by Germans and Ukrainian collaborators, which left mostly ethnic Ukrainian students.

Another “hero” commemorated by Ivano-Frankivsk’s program is Stepan Koval (1914–2001), commander of Lutsk’s Ukrainian police academy established with the approval of the Nazis (the academy’s insignia prominently featured a swastika). Lutsk’s local auxiliary police played a key role in the murder of over 20,000 of the city’s Jews. Later, Koval commanded a unit in the UPA which participated in the ethnic cleansing of Polish villages. His plaque is in his home village of Mykytyntsi, right outside Ivano-Frankivsk.

The heroes program also erected a plaque for Mykhailo Mulyk (1920–2020), SS Galichina veteran who annually celebrated the unit’s founding. (The plaque features a photograph of Mulyk in his SS uniform but with the SS insignia blurred out; see above) Mulyk received a separate memorial sign on Ivano-Frankivsk’s walk of fame as well. See the JTA on condemnation of SS Galichina marches which frequently feature Nazi salutes.

These plaques are in Ivano-Frankivsk, where the Nazis together with Ukrainian collaborators, exterminated over 20,000 Jews; no more than 1,500 of the city’s Jews survived.

Kalush – In 2018 this city unveiled a bas-relief honoring SS Galichina officer Yurii Harasymiv (1899–1975). Media coverage of the event described Harasymiv as a Waffen-SS officer the way American media describes U.S. Army veterans, which isn’t surprising given how openly this SS division is celebrated in Ukraine. Above left, Garasymiv (circled) at SS training, 1943.

Sivka-Voinylivska – A plaque to Lyubomir Makarushka (1899–1986), Waffen-Obersturmführer in SS Galichina. After the war, Makarushka lived in West Germany. Note the SS Galichina collar patch insignia on the plaque; the Anti-Defamation League classifies SS divisional insignia as neo-Nazi hate symbols.

Malyi Khodachkiv – a plaque honoring SS Galichina fighter Teodor Barabash (1923–2014). After the war, Barabash emigrated to Spain, where he became a businessman and leader of the country’s Ukrainian diaspora. Above left, Barabash with Iosif Slipyi who was deeply involved in the creation of SS Galichina (see entry above).

Perehyn’ske – A memorial to hometown fighter Volodymyr Deputat (1918–1946) who served in SS Galichina before joining the UPA.

Ivano-Frankivsk and Chernihiv – Both have streets for Ivan Rembolovich (1897–1950), decorated SS Galichina officer.

(Note: The Chernihiv street was added August 2023.)

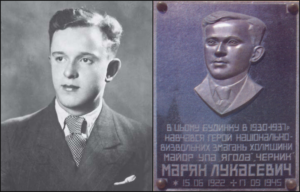

Ternopil – On the façade of a Ternopil school is a plaque celebrating one of its graduates, Mar’yan Lukasevich (1922–1945). Lukasevich served in SS Galichina before becoming a UPA commander. The plaque describes him as a hero of the “national liberation” movement.

Voinyliv – A plaque to town native Roman Rudyi (1923–2005), who served in SS Galichina. The plaque calls him a “civil and political activist and a political prisoner.” Above right, Governor of Galizia Otto Wächter (far left) and Governor-General of Poland Hans Frank (third from left) inspect SS Galichina volunteers in L’viv, June 1943.

Ivano-Frankivsk and two other locales – Both Ivano-Frankivsk and Ternopil have streets and memorials dedicated to the SS Galichina division as a whole. Ivano-Frankivsk’s memorial (above left) thanks the “heroes” of the Ukrainian Division Galicia (another name for SS Galichina) as well as OUN and UPA fighters.

Ternopil commemorates SS Galichina’s founding with a promenade in the city’s beautiful Topil’che Park; above right, a memorial at one end of the promenade. The city also has an SS Galichina street. Additionally, there’s an SS Galichina museum in L’viv. For more SS Galichina memorials, see the Austria, Australia and Canada sections.

Nizhyn and four other locales – The city’s “Wall of Heroes” has a plaque jointly honoring Pavlo Shandruk (1889–1979) and Iosyp Pozychanyuk (1913–1944). Shandruk, one of the highest ranked Ukrainians in the Third Reich, was commanding general of the Ukrainian National Army, a part of the Wehrmacht (Nazi Germany’s armed forces). After the war, Shandruk (above left) moved to America. He also has a plaque on a school in Borsuky and streets in Ivano-Frankivsk and Pervomaisk (Mykolayiv Oblast).

Pozychanyuk was minister of propaganda in the OUN-B’s 1941 Nazi collaborationist government (see Ivan Klymiv entry above for more). Later, Pozychanyuk became a lieutenant-colonel running propaganda for the UPA. He also has a memorial bas-relief in his home village of Dashiv.

(Note: Shandruk’s Pervomaisk (Mykolayiv Oblast) street was added June 2025.)

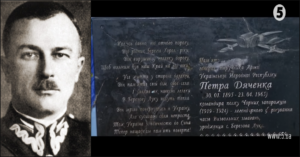

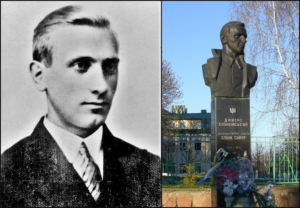

Berezova Luka and six other locales – In the village of Berezova Luka is a memorial plaque and museum to Petro Dyachenko (1895–1965). Dyachenko, like Pavlo Shandruk (see entry above), was a general in the Ukrainian National Army; for his services, Dyachenko was personally awarded the Iron Cross by Third Reich general Wilhelm Schmalz. Toward the end of the war, Dyacheko was also attached to SS Galichina. Dyachenko, who later emigrated to America, also has streets in Bila Tserkva, Nikopol’, Pervomaisk (Mykolayiv Oblast), Voznesensk, Zhmerynka and Zolotonosha.

(Note: The Nikopol’ street was added March 2024; the Bila Tserkva, Pervomaisk (Mykolayiv Oblast), Zhmerynka and Zolotonosha streets were added June 2025.)

Zbarazh (Ternopil Oblast) and eight other locales – Prominent OUN leader Dmytro Kliachkivskyi (1911–1945) aka Klym Savur, played a key role in forming the UPA in 1943. Kliachkivskyi eventually became commander of the UPA-North district which operated around the Volyn region. There, Kliachkivskyi became one of the organizers of the Volyn massacres – the 1943 ethnic cleansing campaign that brutally murdered 70,000–100,000 Polish civilians, many of them children. The UPA murdered thousands of Jews as well.

In addition to the monument in his home town of Zbarazh, Kliachkivskyi has a monument and street in Rivne; a plaque on a joint monument to him and other OUN leaders in Morshyn; and streets in Dubno (Rivne Oblast), Korost, Kostopil, Lutsk, Stryi and Ternopil.

Ternopil and three other locales – Four monuments commemorating the OUN as a whole. The towering cross honoring “Heroes of OUN and the UPA,” (above right) is located in Bolekhiv, which had a thriving population of 3,000 Jews; no more than 50 survived massacres by Nazis and Ukrainian collaborators. See “The Lost: A Search for Six of Six Million” by Daniel Mendelsohn, the documentary “Neighbors and Murderers” and Yahad-In Unum for more on the Holocaust in Bolekhiv. There are two other monuments in Vinnytsia and Volodymyr-Volyns’kyi.

(Note: The Vinnytsia and Volodymyr-Volyns’kyi monuments were added June 2025.)

For monuments to Ukrainian Nazi collaborators outside of Ukraine, see the U.S., Canada, Argentina, Germany, U.K., Austria, Australia and Italy sections.

Ukraine is erecting new plaques and monuments to Nazi collaborators on a nearly weekly basis. Eduard Dolinsky of the Ukrainian Jewish Committee chronicles this explosion of Nazi collaborator whitewashing on Twitter, and wrote about it in the New York Times. For more on Ukraine’s state-sponsored Holocaust revisionism see The Nation, Foreign Policy, Open Democracy, a press release from the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum and Defending History’s Ukraine page.

Correction: The original caption with the photograph of Yaroslav Stetsko meeting with then-U.S. Vice President George H. W. Bush misstated the year it was taken. It was 1983, not 1943.