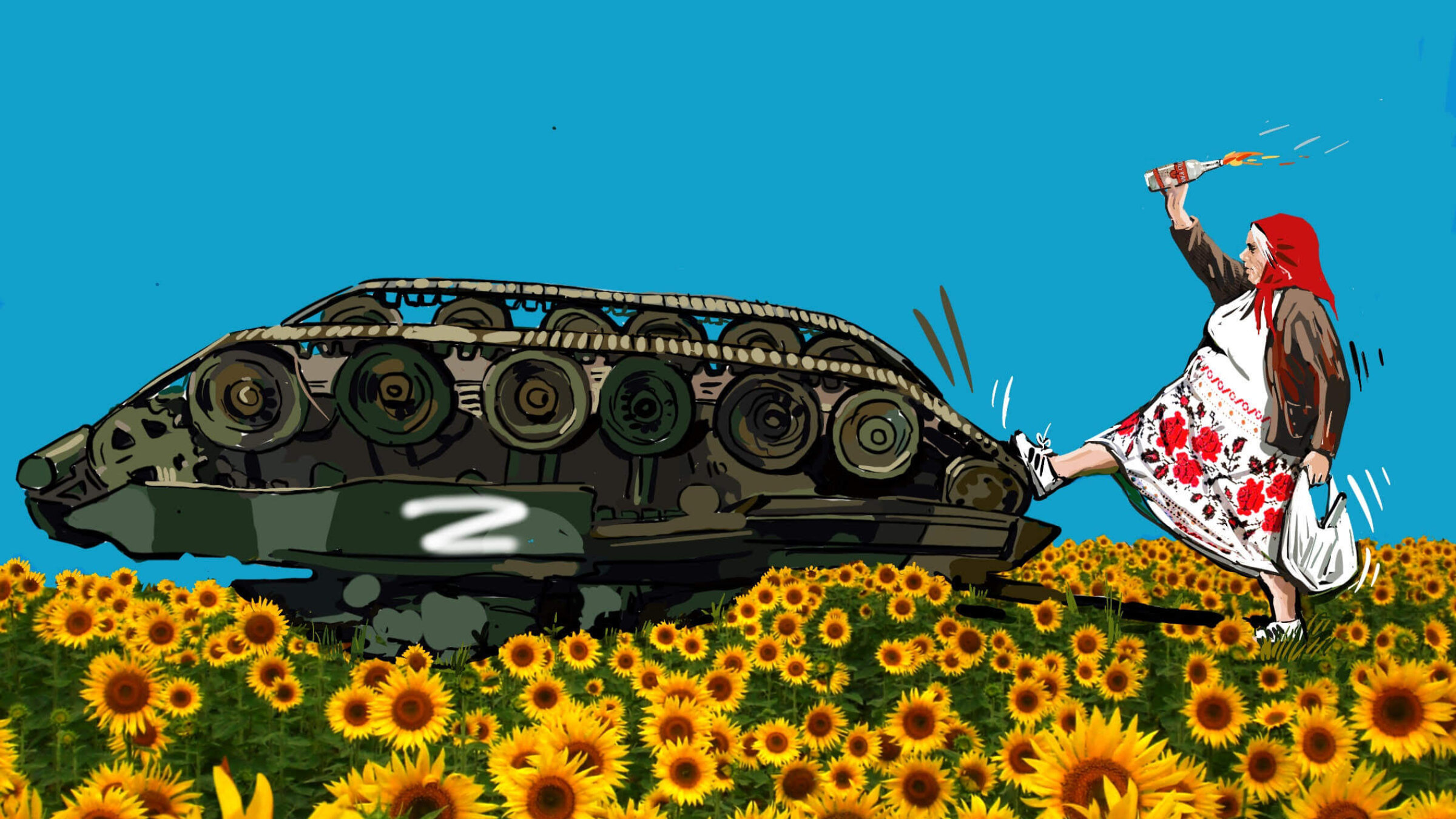

Putin is no match for my Jewish Ukrainian babushka

With a little Krav Maga training, my grandmother is a force to be reckoned with.

Graphic by Nikki Casey

When I was in the fourth grade, I came home from school one afternoon to find my babushka’s warm cheese blintzes waiting for me on the kitchen table, but my babushka was nowhere in sight. Instead, my grandma, Hannah, had gone to see our neighbor Avi, a former special-ops officer in the Israeli Defense Forces, who had offered to train her in Krav Maga, a self-defense system that combines boxing, wrestling, and martial arts.

It made sense that a 4-foot-10-inch grandma would want to learn how to defend herself in 1980s New York City. But my babushka didn’t just plan to ward off perps on the mean streets of Queens. She was also intent on socking it to her personal enemies, or vragi, the worst of whom was her son-in-law—my dad, Vlad.

He wasn’t good enough for her only child, my mom Leah, an upstanding doctor. He was a boxer-turned-taxi driver with a filthy mouth, a wandering eye, a penchant for vodka, and a freewheeling way with cash. His fatal flaw, however, was that he was Russian.

Though he was a Jew born during the Siege of Leningrad, in which he lost his brother to the Nazis at the front and other relatives to starvation at home, when my Ukrainian babushka looked at him, she saw Lenin, Stalin, and Khrushchev combined, which made her simmer with rage.

Babushkas have endured war, famine, and genocide, so they have zero tolerance for fools. They will send you to your grave with a Yiddish curse as easily as they will strangle you with their bare hands. And, of course, they will fight to the death for their homeland, like babushkas are doing right now in Putin’s barbaric war on Ukraine.

A babushka named Elena reportedly took down a suspicious drone with a jar of pickled tomatoes. 72-year-old babushka-of-three Galyna spearheaded a Molotov cocktail-making operation out of her Kyiv apartment building. Some babushkas are using their iPhones to call in the locations of Russian units while others are brandishing AK-47 assault rifles to fight Russian soldiers.

Defiance is ingrained in the Ukrainian spirit. It has built up through a long history of oppression, and Jews in Ukraine, in particular, have faced some of the cruelest antisemitism of the 20th century. When the Nazis occupied the Soviet Union in 1941, the Holocaust in Ukraine was the first phase of the genocide in which about 1.5 million Jews were shot to death at close range in a “Holocaust by Bullets.”

Even after World War II, through the Khrushchev years and beyond, systemic antisemitism persisted. Jews couldn’t practice their religion, faced discrimination in the workplace, and had limited economic opportunities (though socialism was also to blame). As a result, many Jews, including my immediate and extended family, fled to the United States in the ‘70s and ‘80s.

At our Forest Hills apartment building full of striving immigrants, the bosses were the babushkas who marched through the streets with grocery bags filled with pierogies, kielbasas, caviar and other delicacies—and hunted vragi all the way from Woodhaven Boulevard to Grand Central Parkway.

After my babushka had taken a few classes with Avi, she roped in my cousins’ babushkas, Esther and Bella. My cousins and I peeked into Avi’s apartment a few times a week to see our babushkas shielding, punching, and kicking. Soon, they were strutting through Key Food with a Krav Maga swagger.

Because Krav Maga teaches people to constantly anticipate attacks and to think strategically in an instant, it made my already suspicious babushka extra paranoid and combative—especially when it came to my dad.

His mere existence was suspect. What was even worse than his living and breathing was his overblown generosity. The common refrain among my dad’s friends was “Vlad pay.” Vlad pay for restaurant. Vlad pay for banya, or Russian bath. Vlad pay for off-track betting. In other words, my dad allowed leeches in the tri-state area and beyond to suck the blood out of our bank account.

“He isn’t just taking food out of his family’s mouth. He’s orchestrating mass starvation of the Ukrainian people!” my babushka proclaimed. To her, my father was a foul-mouthed, vodka-loving Stalin. The more he cursed and partied, the more she criticized him. The more she criticized him, the more he cursed and partied.

Opinions on the cold war brewing in our apartment were mixed. Some friends and relatives believed my babushka should’ve kicked my dad’s ass already, while others thought he was a saint for letting my grandparents live with us, and this was one situation in which elder abuse would be justified.

Then, there was an escalation. My dad started dressing more dapper, staying out nights, and having secretive conversations on the phone. We were also getting hang-up calls. My babushka heard from her spies Esther and Bella that he was “shtupping a shluha”—screwing a slut—who lived in nearby Rego Park, and it had been going on for a while. Not wanting to be accessories to murder, they wouldn’t divulge her name to my babushka.

The hang-up calls soon had a baby crying in the background, which meant my dad had fathered a ubludok—a bastard. Because he was “carrying out a pogrom on his own family,” my babushka prepared for combat.

One afternoon, my babushka and I were buying some brisket at Key Food. Standing in line next to us was a plain young woman with a stroller. When her baby started crying and she picked him up to comfort him, my babushka zeroed in on his face. She shot me a knowing look.

“I don’t think he looks that much like him,” I whispered as she sneered at me. Then, she turned to the young woman and asked her, “Whose baby is that? Because he looks just like a ubludok!” The woman gasped, shielding her baby from an imminent attack.

“You can’t hurt a baby—that’s a war crime!” I exclaimed as I grabbed the brisket and ushered my babushka out of Key Food.

At our apartment, she waited for my dad to come home from work while my pulse quickened at the thought of my tiny babushka fighting my boxer dad. When he walked through the door, she pounced on him. He put her in a bear hug to immobilize her, but she did a fast squat, escaping his grip.

Veering toward him, she smashed his nose with her palm. He screamed, about to strike her, but stopped himself. He’d never hit a woman—especially a babushka—and she knew it. So, she went in with a horizontal elbow strike as he tried in vain to block her.

Avenging war, famine, genocide and adultery, she kneed him in the groin, knocking him out. My grandpa Isaac, my dedushka, counted for 10 seconds as my dad lay there, out for the count, while my mom knelt next to him with smelling salts. Then, my dedushka raised my babushka’s fist in victory.

The hang-up calls stopped and my dad started spending more time at home. About a year later my brother was born. Having a son turned my dad into a family man. Though he eventually started partying again, my babushka’s watchful eye and iron fist reined him in.

A couple of days ago I sat at my kitchen table, eating the cheese blintzes I made with my babushka’s recipe and thinking of the badass babushkas currently defending Ukraine with iPhones, Molotovs, and AK-47s in Russia’s brutal war. Sometimes, I fear that they’re no match for Russia’s military strength and savagery.

But in recalling my dad passed out on the floor, my triumphant babushka standing over him, I realize that we shouldn’t underestimate the power of one’s love for their family and homeland, and the force of sheer will.

As defense expert John Arquilla recently said, “Grandmas with iPhones can trump satellites.” Putin should know better than to mess with babushkas.

To contact the author, email [email protected]